Training Large Language Models to Reason in a Continuous Latent Space

Show me an executive summary.

Purpose and Context

Large language models currently reason by generating explicit step-by-step explanations in natural language—a method called chain-of-thought (CoT). However, language may not be optimal for reasoning. Most words in a reasoning chain exist only for readability and contribute little to solving the problem, while critical decision points require complex planning that language-based models handle poorly. This work explores whether models can reason more effectively in a continuous mathematical space rather than being constrained to words.

Approach

The research team developed Coconut (Chain of Continuous Thought), which allows models to perform intermediate reasoning steps as continuous mathematical representations instead of converting each step into words. The model switches between "language mode" (generating readable text) and "latent mode" (reasoning in continuous space). During latent mode, the model's internal state is fed directly back as input without being decoded into words.

Training uses a multi-stage curriculum starting with standard language-based reasoning, then progressively replacing language steps with continuous thoughts. The model learns through standard optimization on datasets requiring mathematical reasoning (GSM8k) and logical reasoning (ProntoQA and a newly created dataset, ProsQA, designed to require extensive planning).

Key Findings

Coconut enables a fundamentally different reasoning pattern. Unlike language-based reasoning that commits to one path immediately, continuous thoughts can encode multiple alternative reasoning paths simultaneously. Analysis reveals the model performs breadth-first search—maintaining several candidate solutions and progressively eliminating incorrect options rather than following a single deterministic path.

On logical reasoning tasks requiring substantial planning (ProntoQA and ProsQA), Coconut matches or exceeds traditional CoT accuracy while generating significantly fewer tokens. For example, on ProsQA, Coconut achieves 97% accuracy generating only 14 tokens on average, compared to 77.5% accuracy with 49 tokens for standard CoT. On mathematical reasoning (GSM8k), Coconut achieves 34% accuracy with 8 tokens versus 43% for CoT with 25 tokens—offering a better accuracy-efficiency trade-off though not surpassing CoT's peak performance.

The improvement stems from continuous space's ability to delay commitment. Early reasoning steps are harder to evaluate because they're far from the final answer. By encoding multiple options in continuous thoughts, the model can explore paths closer to terminal states where correct versus incorrect paths become clearer.

Significance and Implications

These results demonstrate that language, while essential for communication, may unnecessarily constrain machine reasoning. Continuous space reasoning offers two practical advantages: higher efficiency (fewer generated tokens means lower computational cost during inference) and better handling of tasks requiring search and planning.

The findings challenge the assumption that reasoning processes must mirror human linguistic expression. The model develops parallel search capabilities without being explicitly trained to do so—an emergent property of removing language constraints.

Recommendations and Next Steps

Organizations deploying reasoning models for planning-intensive tasks should consider latent space approaches, particularly where inference costs are significant or where problems involve exploring multiple solution paths.

Key development priorities should include: integrating continuous reasoning into pretraining (current experiments start from pretrained language models), optimizing training efficiency (the current sequential forward passes limit parallelism), and combining language and latent reasoning (using language for high-level structure and continuous thoughts for detailed steps).

Before production deployment, validate performance on domain-specific tasks, as current results focus on mathematical and logical reasoning with relatively small models (GPT-2 scale).

Limitations and Confidence

The experiments use small models (GPT-2, with limited tests on 3B-8B parameter models). Larger pretrained models show smaller improvements, likely because extensive language pretraining makes transitioning to latent reasoning more difficult. The approach requires language-based reasoning chains for training supervision—developing methods to learn effective latent reasoning without this guidance remains unsolved.

Training is less efficient than standard methods due to multiple sequential forward passes. The multi-stage curriculum proves necessary; direct training on continuous thoughts without language guidance fails to learn effective reasoning.

Confidence is high that continuous space reasoning enables parallel search patterns and improves efficiency on the tested logical reasoning tasks. Confidence is moderate that these benefits will generalize to other reasoning domains and scale to larger models without significant additional research into latent space pretraining methods.

Shibo Hao1,2,∗^{1,2,*}1,2,∗, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar1^{1}1, DiJia Su1^{1}1, Xian Li1^{1}1, Zhiting Hu2^{2}2, Jason Weston1^{1}1, Yuandong Tian1^{1}1

1^{1}1 FAIR at Meta

2^{2}2 UC San Diego

∗^{*}∗ Work done at Meta

Large language models (LLMs) are restricted to reason in the "language space", where they typically express the reasoning process with a chain-of-thought (CoT) to solve a complex reasoning problem. However, we argue that language space may not always be optimal for reasoning. For example, most word tokens primarily ensure textual coherence and are not essential for reasoning, while some critical tokens require complex planning and pose huge challenges to LLMs. To explore the potential of LLM reasoning in an unrestricted latent space instead of using natural language, we introduce a new paradigm COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT (Chain of Continuous Thought). We utilize the last hidden state of the LLM as a representation of the reasoning state (termed "continuous thought"). Rather than decoding this into a word token, we feed it back to the LLM as the subsequent input embedding directly in the continuous space. This latent reasoning paradigm leads to the emergence of an advanced reasoning pattern: the continuous thought can encode multiple alternative next reasoning steps, allowing the model to perform a breadth-first search (BFS) to solve the problem, rather than prematurely committing to a single deterministic path like CoT. COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT outperforms CoT on certain logical reasoning tasks that require substantial search during planning, and shows a better trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

1. Introduction

In this section, the authors challenge the assumption that natural language is the optimal medium for LLM reasoning, noting that while chain-of-thought reasoning has proven effective, it forces models to express all reasoning steps as word tokens—a constraint at odds with neuroscience findings showing that human language networks remain inactive during many reasoning tasks. The core problem is that language-based reasoning allocates uniform computational resources across all tokens, even though most serve only to maintain fluency while a few critical tokens demand complex planning. To address this, the authors introduce Coconut (Chain of Continuous Thought), which allows LLMs to reason in an unrestricted latent space by feeding hidden states directly back as input embeddings rather than decoding them into tokens. This approach enables an emergent breadth-first search pattern where continuous thoughts encode multiple reasoning paths simultaneously, allowing progressive elimination of incorrect options. Experiments demonstrate that Coconut outperforms traditional chain-of-thought on logical reasoning tasks requiring substantial planning while generating fewer tokens during inference.

Large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable reasoning abilities, emerging from extensive pretraining on human languages [1, 2]. While next token prediction is an effective training objective, it imposes a fundamental constraint on the LLM as a reasoning machine: the explicit reasoning process of LLMs must be generated in word tokens. For example, a prevalent approach, known as chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning [3], involves prompting or training LLMs to generate solutions step-by-step using natural language. However, this is in stark contrast to certain human cognition results. Neuroimaging studies have consistently shown that the language network – a set of brain regions responsible for language comprehension and production – remains largely inactive during various reasoning tasks [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Further evidence indicates that human language is optimized for communication rather than reasoning [9].

A significant issue arises when LLMs use language for reasoning: the amount of reasoning required for each particular token varies greatly, yet current LLM architectures allocate nearly the same computing budget for predicting every token. Most tokens in a reasoning chain are generated solely for fluency, contributing little to the actual reasoning process. By contrast, some critical tokens require complex planning and pose huge challenges to LLMs. While previous work has attempted to fix these problems by prompting LLMs to generate succinct reasoning chains [10], or performing additional reasoning before generating some critical tokens [11], these solutions remain constrained within the language space and do not solve the fundamental problems. On the contrary, it would be ideal for LLMs to have the freedom to reason without any language constraints, and then translate their findings into language only when necessary.

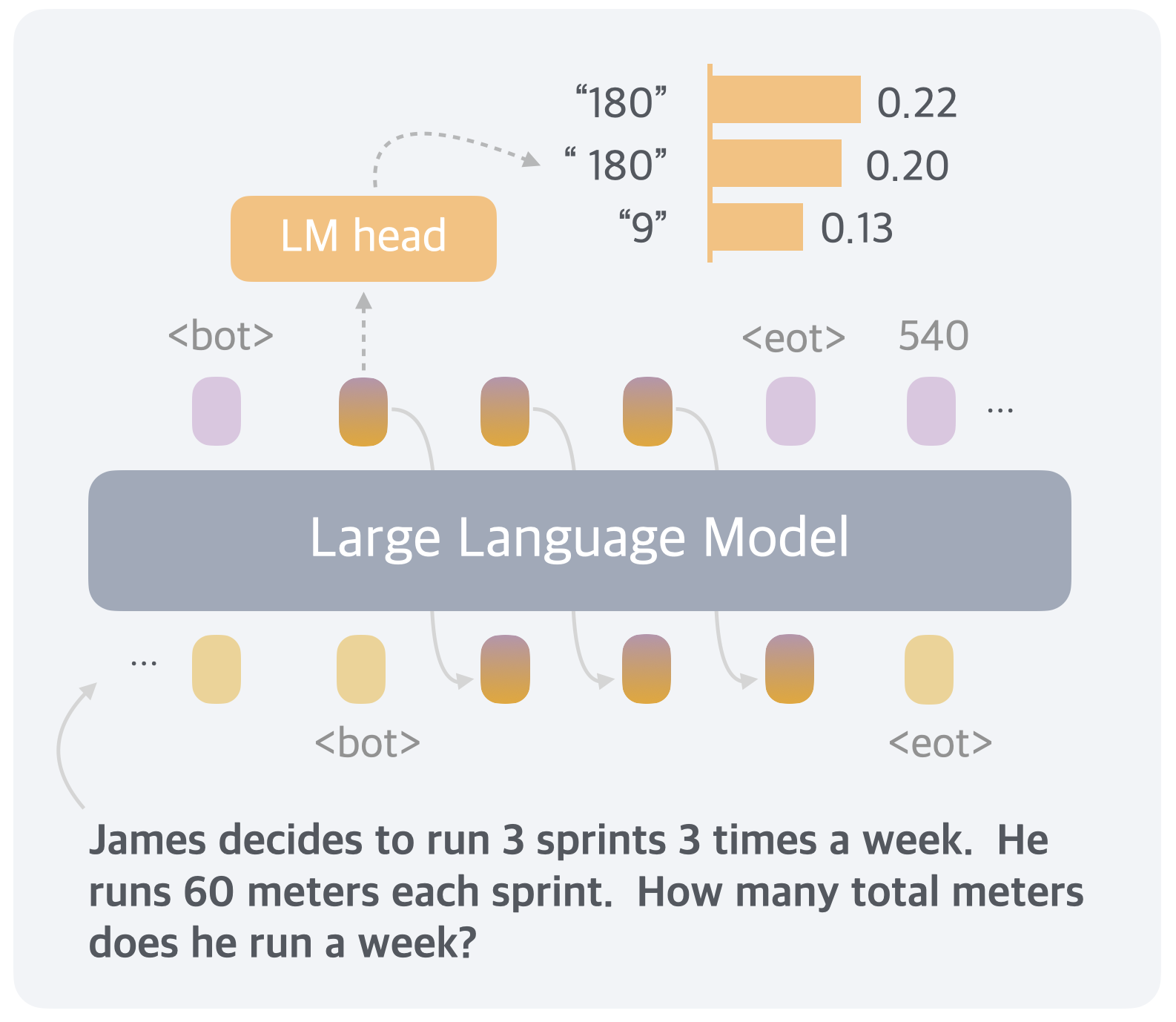

In this work we instead explore LLM reasoning in a latent space by introducing a novel paradigm, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT (Chain of Continuous Thought). It involves a simple modification to the traditional CoT process: instead of mapping between hidden states and language tokens using the language model head and embedding layer, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT directly feeds the last hidden state (a continuous thought) as the input embedding for the next token (Figure 1). This modification frees the reasoning from being within the language space, and the system can be optimized end-to-end by gradient descent, as continuous thoughts are fully differentiable. To enhance the training of latent reasoning, we employ a multi-stage training strategy inspired by [12], which effectively utilizes language reasoning chains to guide the training process.

Interestingly, our proposed paradigm leads to an efficient reasoning pattern. Unlike language-based reasoning, continuous thoughts in COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT can encode multiple potential next steps simultaneously, allowing for a reasoning process akin to breadth-first search (BFS). While the model may not initially make the correct decision, it can maintain many possible options within the continuous thoughts and progressively eliminate incorrect paths through reasoning, guided by some implicit value functions. This advanced reasoning mechanism surpasses traditional CoT, even though the model is not explicitly trained or instructed to operate in this manner, as seen in previous works [13, 14].

Experimentally, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT successfully enhances the reasoning capabilities of LLMs. For math reasoning ProntoQA [16], using continuous thoughts is shown to be beneficial to reasoning accuracy, mirroring the effects of language reasoning chains. This indicates the potential to scale and solve increasingly challenging problems by chaining more continuous thoughts. On logical reasoning including ProntoQA [16], and our newly proposed ProsQA (Section 4) which requires stronger planning ability, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT and some of its variants even surpasses language-based CoT methods, while generating significantly fewer tokens during inference. We believe that these findings underscore the potential of latent reasoning and could provide valuable insights for future research.

2. Related Work

In this section, the authors situate their work within two main research areas: chain-of-thought reasoning and latent reasoning in LLMs. Chain-of-thought methods, whether through prompting or training, generate intermediate reasoning steps in natural language before producing final answers, with theoretical work showing this increases transformer depth by looping outputs back as inputs. However, CoT's autoregressive nature makes it difficult to handle complex problems requiring planning and search, prompting researchers to augment LLMs with explicit search algorithms or train on search trajectories. Latent reasoning work has explored hidden computations in transformers, discovering that models can recover intermediate variables from representations and may use different reasoning processes than their generated CoT suggests. Recent approaches enhance latent reasoning through pause tokens or by internalizing CoT via distillation and curriculum learning—a strategy the authors adopt by breaking continuous thought learning into multiple training stages. Unlike prior work on alternative architectures or token augmentation, this research investigates latent reasoning's unique properties compared to language space on general multi-step reasoning tasks.

Chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning. We use the term chain-of-thought broadly to refer to methods that generate an intermediate reasoning process in language before outputting the final answer. This includes prompting LLMs ([3, 18, 19]), or training LLMs to generate reasoning chains, either with supervised finetuning ([20, 21]) or reinforcement learning ([22, 23, 24, 25]). [10] classified the tokens in CoT into symbols, patterns, and text, and proposed to guide the LLM to generate concise CoT based on analysis of their roles. Recent theoretical analyses have demonstrated the usefulness of CoT from the perspective of model expressivity ([26, 27, 28]). By employing CoT, the effective depth of the transformer increases because the generated outputs are looped back to the input ([26]). These analyses, combined with the established effectiveness of CoT, motivated our design of feeding the continuous thoughts back into the LLM as input embeddings. While CoT has proven effective for certain tasks, its autoregressive generation nature makes it challenging to mimic human reasoning on more complex problems ([29, 14]), which typically require planning and search. There are works that equip LLMs with explicit tree search algorithms ([30, 13, 31]), or train the LLM on search dynamics and trajectories ([17, 32, 33]). In our analysis, we find that after removing the constraint of a language space, a new reasoning pattern similar to BFS emerges, even though the model is not explicitly trained in this way.

Latent reasoning in LLMs. Previous works mostly define latent reasoning in LLMs as the hidden computation in transformers ([34, 35]). [34] constructed a dataset of two-hop reasoning problems and discovered that it is possible to recover the intermediate variable from the hidden representations. [35] further proposed to intervene the latent reasoning by "back-patching" the hidden representation. [36] discovered parallel latent reasoning paths in LLMs. Another line of work has discovered that, even if the model generates a CoT to reason, the model may actually utilize a different latent reasoning process. This phenomenon is known as the unfaithfulness of CoT reasoning~([37, 38]). To enhance the latent reasoning of LLMs, previous research proposed to augment it with additional tokens. [39] pretrained the model by randomly inserting a learnable <pause> tokens to the training corpus. This improves LLM's performance on a variety of tasks, especially when followed by supervised finetuning with <pause> tokens. On the other hand, [40] further explored the usage of filler tokens, e.g., '``...`'', and concluded that they work well for highly parallelizable problems. However, [40] mentioned these methods do not extend the expressivity of the LLM like CoT; hence, they may not scale to more general and complex reasoning problems. [44] proposed to predict a planning token as a discrete latent variable before generating the next reasoning step. Recently, it has also been found that one can "internalize" the CoT reasoning into latent reasoning in the transformer with knowledge distillation [45] or a special training curriculum which gradually shortens CoT [12]. [46] also proposed to distill a model that can reason latently from data generated with complex reasoning algorithms. These training methods can be combined to our framework, and specifically, we find that breaking down the learning of continuous thoughts into multiple stages, inspired by iCoT [12], is very beneficial for the training. Other work explores alternative architectures for latent reasoning, including looped transformers [47, 48], diffusion models in sentence embedding space [42]. Different from these works, we focus on general multi-step reasoning tasks and aim to investigate the unique properties of latent reasoning in comparison to language space. In addition to reasoning tasks, [49] also explored using continuous space for multi-agent communication. Building on COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT , [50] developed a theoretical framework demonstrating that continuous CoT can be more efficient than discrete CoT on certain tasks by encoding multiple reasoning paths in superposition states. Subsequently, [51] analyzed the training dynamics to explain how such superposition emerges under the COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT training objective.

3. COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT : Chain of Continuous Thought

In this section, we introduce our new paradigm COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT (Chain of Continuous Thought) for reasoning in an unconstrained latent space. We begin by introducing the background and notation we use for language models. For an input sequence x=(x1,...,xT)x = (x_1, ..., x_T)x=(x1,...,xT), the standard large language model M\mathcal{M}M can be described as:

where Et=[e(x1),e(x2),...,e(xt)]E_t = [e(x_1), e(x_2), ..., e(x_t)]Et=[e(x1),e(x2),...,e(xt)] is the sequence of token embeddings up to position ttt; Ht∈Rt×dH_t \in \mathbb{R}^{t \times d}Ht∈Rt×d is the matrix of the last hidden states for all tokens up to position ttt; hth_tht is the last hidden state of position ttt, i.e., ht=Ht[t,:]h_t=H_t[t, :]ht=Ht[t,:]; e(⋅)e(\cdot)e(⋅) is the token embedding function; WWW is the parameter of the language model head.

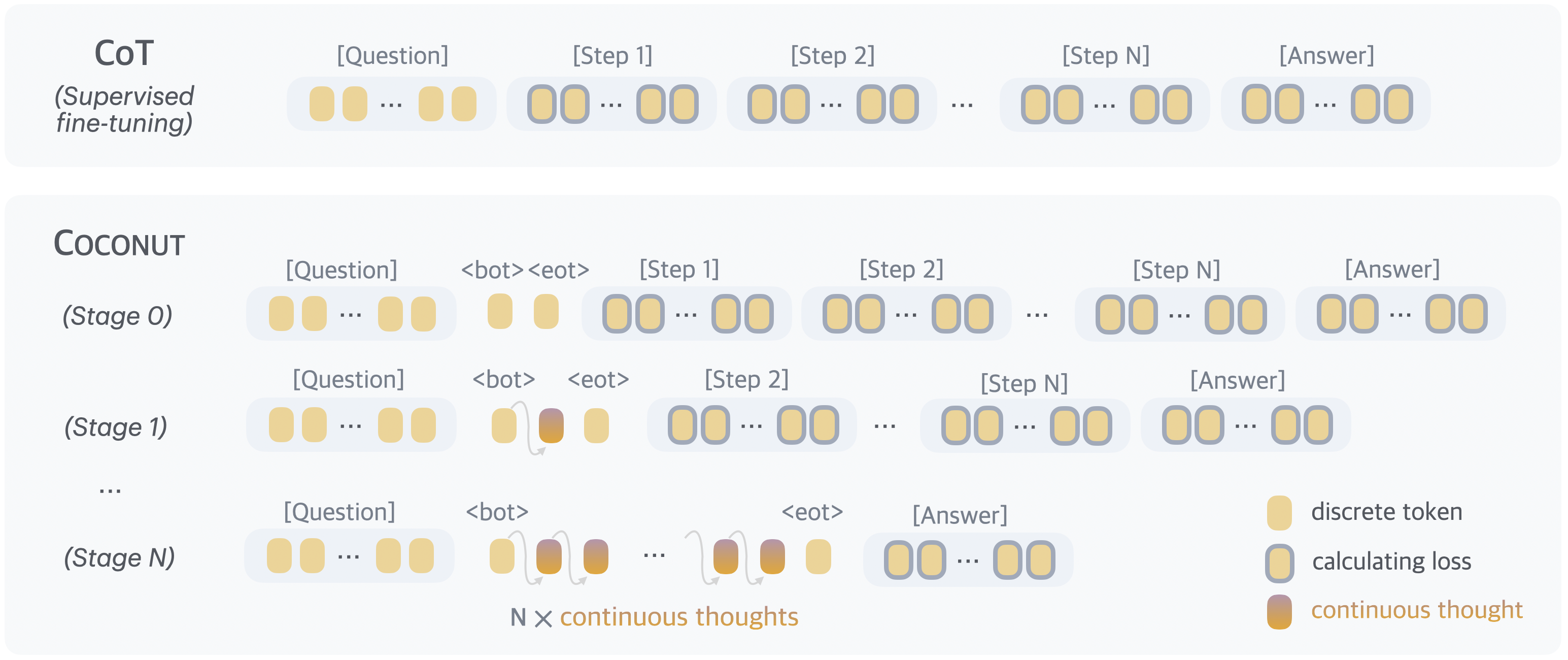

Method Overview. In the proposed COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT method, the LLM switches between the "language mode" and "latent mode" (Figure 1). In language mode, the model operates as a standard language model, autoregressively generating the next token. In latent mode, it directly utilizes the last hidden state as the next input embedding. This last hidden state represents the current reasoning state, termed as a "continuous thought".

Special tokens <bot> and <eot> are employed to mark the beginning and end of the latent thought mode, respectively. As an example, we assume latent reasoning occurs between positions iii and jjj, i.e., xi=x_i=xi= <bot> and xj=x_j=xj= <eot>. When the model is in the latent mode (i<t<ji < t < ji<t<j), we use the last hidden state from the previous token to replace the input embedding, i.e., Et=[e(x1),e(x2),...,e(xi),hi,hi+1,...,ht−1]E_t=[e(x_1), e(x_2), ..., e(x_i), h_i, h_{i+1}, ..., h_{t-1}]Et=[e(x1),e(x2),...,e(xi),hi,hi+1,...,ht−1]. After the latent mode finishes (t≥jt \ge jt≥j), the input reverts to using the token embedding, i.e., Et=[e(x1),e(x2),...,e(xi),hi,hi+1,...,hj−1,e(xj),...,e(xt)]E_t=[e(x_1), e(x_2), ..., e(x_i), h_i, h_{i+1}, ..., h_{j-1}, e(x_j), ..., e(x_t)]Et=[e(x1),e(x2),...,e(xi),hi,hi+1,...,hj−1,e(xj),...,e(xt)]. It is worth noting that the last hidden states have been processed by the final normalization layer, so they are not too large in magnitude. M(xt+1∣x≤t)\mathcal{M}(x_{t+1}\mid x_{\leq t})M(xt+1∣x≤t) is not defined when i<t<ji<t<ji<t<j, since the latent thought is not intended to be mapped back to language space. However, softmax(Wht)\mathrm{softmax}(Wh_t)softmax(Wht) can still be calculated for probing purposes (see Section 5).

Training Procedure. In this work, we focus on a problem-solving setting where the model receives a question as input and is expected to generate an answer through a reasoning process. We leverage language CoT data to supervise continuous thought by implementing a multi-stage training curriculum inspired by [12]. As shown in Figure 2, in the initial stage, the model is trained on regular CoT instances. In the subsequent stages, at the kkk-th stage, the first kkk reasoning steps in the CoT are replaced with k×ck \times ck×c continuous thoughts, where ccc is a hyperparameter controlling the number of latent thoughts replacing a single language reasoning step. Following [12], we also reset the optimizer state when training stages switch. We insert <bot> and <eot> tokens (which are not counted towards ccc) to encapsulate the continuous thoughts.

During the training process, we optimize the normal negative log-likelihood loss, but mask the loss on questions and latent thoughts. It is important to note that the objective does not encourage the continuous thought to compress the removed language thought, but rather to facilitate the prediction of future reasoning. Therefore, it's possible for the LLM to learn more effective representations of reasoning steps compared to human language.

Training Details. Our proposed continuous thoughts are fully differentiable and allow for back-propagation. We perform n+1n+1n+1 forward passes when nnn latent thoughts are scheduled in the current training stage, computing a new latent thought with each pass and finally conducting an additional forward pass to obtain a loss on the remaining text sequence. While we can save any repetitive computing by using a KV cache, the sequential nature of the multiple forward passes poses challenges for parallelism. Further optimizing the training efficiency of COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT remains an important direction for future research.

Inference Process. The inference process for COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT is analogous to standard language model decoding, except that in latent mode, we directly feed the last hidden state as the next input embedding. A challenge lies in determining when to switch between latent and language modes. As we focus on the problem-solving setting, we insert a <bot> token immediately following the question tokens. For <eot>, we consider two potential strategies: a) train a binary classifier on latent thoughts to enable the model to autonomously decide when to terminate the latent reasoning, or b) always pad the latent thoughts to a constant length. We found that both approaches work comparably well. Therefore, we use the second option in our experiment for simplicity, unless specified otherwise.

4. Continuous Space Enables Latent Tree Search

In this section, the authors demonstrate that continuous latent space reasoning in COCONUT enables a form of breadth-first search that outperforms traditional language-based chain-of-thought on planning-intensive tasks. They introduce ProsQA, a logical reasoning dataset requiring sophisticated path-finding through directed acyclic graphs, and show that COCONUT achieves higher accuracy than standard CoT by maintaining multiple candidate reasoning paths simultaneously rather than committing prematurely to single deterministic steps. By probing intermediate continuous thoughts and forcing the model to decode them into language, they reveal that the model assigns probability values to multiple nodes in parallel, resembling an implicit value function that assesses each node's potential for reaching the correct answer. Critically, nodes farther from terminal states (higher "height") receive more ambiguous evaluations, while nodes closer to solutions are assessed with greater confidence. This explains why delaying deterministic decisions through latent reasoning enhances performance: it allows the model to progressively eliminate incorrect paths as uncertainty decreases, yielding superior planning capabilities on complex reasoning problems.

In this section, we provide a proof of concept of the advantage of continuous latent space reasoning. On ProsQA, a new dataset that requires extensive planning ability, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT outperforms language space CoT reasoning. Interestingly, our analysis indicates that the continuous representation of reasoning can encode multiple alternative next reasoning steps. This allows the model to perform a breadth-first search (BFS) to solve the problem, instead of prematurely committing to a single deterministic path like language CoT.

We start by introducing the experimental setup (Section 4.1). By leveraging COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT 's ability to switch between language and latent space reasoning, we are able to control the model to interpolate between fully latent reasoning and fully language reasoning and test their performance (Section 4.2). This also enables us to interpret the latent reasoning process as tree search (Section 4.3). Based on this perspective, we explain why latent reasoning can help LLMs make better decisions (Section 4.4).

4.1 Experimental Setup

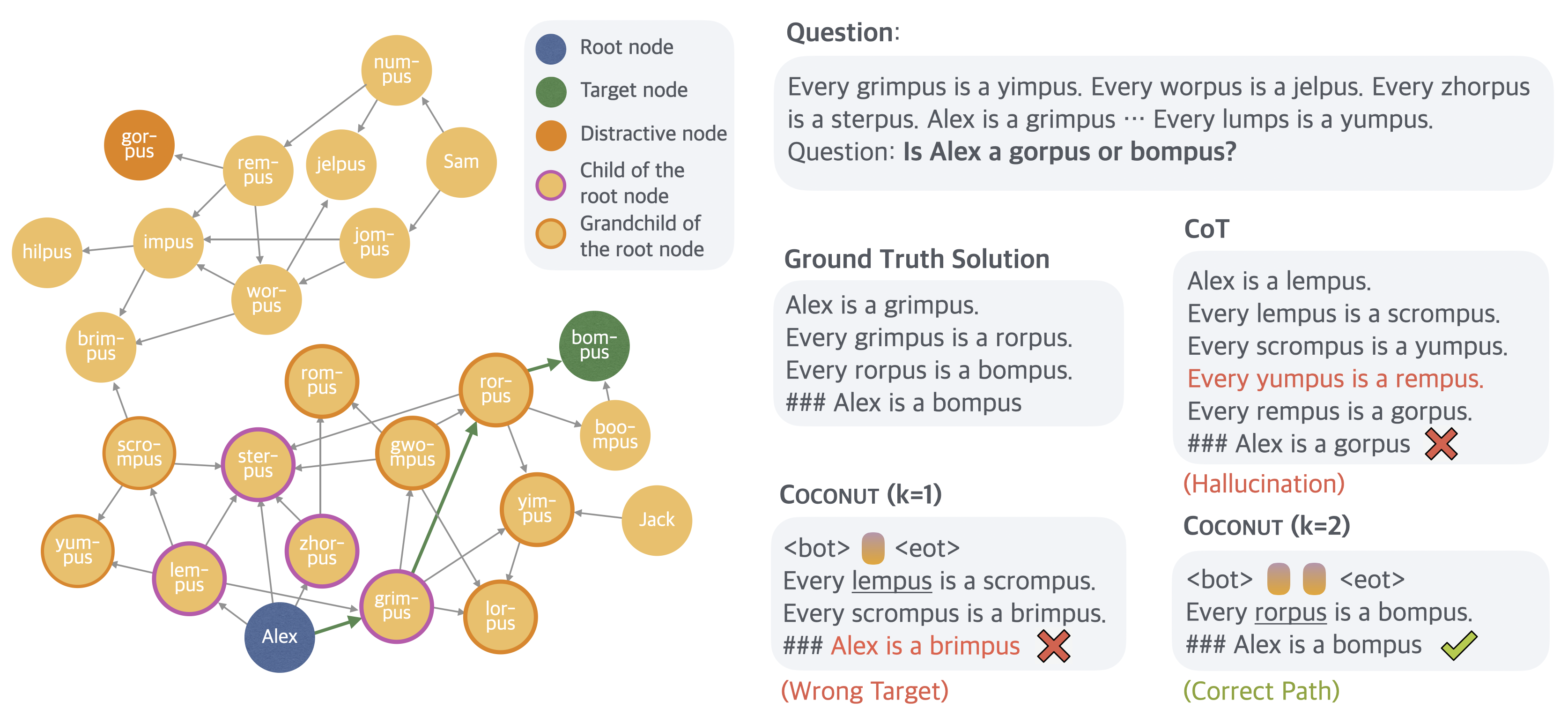

Dataset. We introduce ProsQA (Proof with Search Question-Answering), a new logical reasoning dataset. A visualized example is shown in Figure [@fig:interpret]. Each instance in ProsQA consists of a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of logical relationships between concepts, presented as natural language statements. The task requires models to determine logical relationships by finding valid paths through this graph, demanding sophisticated planning and search strategies. Unlike previous logical reasoning datasets like ProntoQA \citep{saparov2022language}, ProsQA's DAG structure introduces complex exploration paths, making it particularly challenging for models to identify the correct reasoning chain. More comprehensive details about the dataset construction and characteristics can be found in Appendix A.

Setup. We use a pre-trained GPT-2 model as the base model for all experiments. The learning rate is set to 1×10−41\times 10^{-4}1×10−4 while the effective batch size is 128. We train a COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT model following the training procedure in Section 3. Since the maximum reasoning steps in ProsQA is 6, we set the number of training stages to N=6N=6N=6 in the training procedure. In each stage, we train the model for 5 epochs, and stay in the last stage until the 50 epochs. The checkpoint with the best accuracy in the last stage is used for evaluation. As reference, we report the performance of (1) CoT: the model is trained with CoT data, and during inference, the model will generate a complete reasoning chain to solve the problem. (2) no-CoT: the model is trained with only the question and answer pairs, without any reasoning steps. During inference, the model will output the final answer directly.

To understand the properties of latent and language reasoning space, we manipulate the model to switch between fully latent reasoning and fully language reasoning, by manually setting the position of the <eot> token during inference. When we enforce COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT to use kkk continuous thoughts, the model is expected to output the remaining reasoning chain in language, starting from the k+1k+1k+1 step. In our experiments, we test variants of COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT on ProsQA with k∈{0,1,2,3,4,5,6}k \in \{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}k∈{0,1,2,3,4,5,6}. Note that all these variants only differ in inference time while sharing the same model weights.

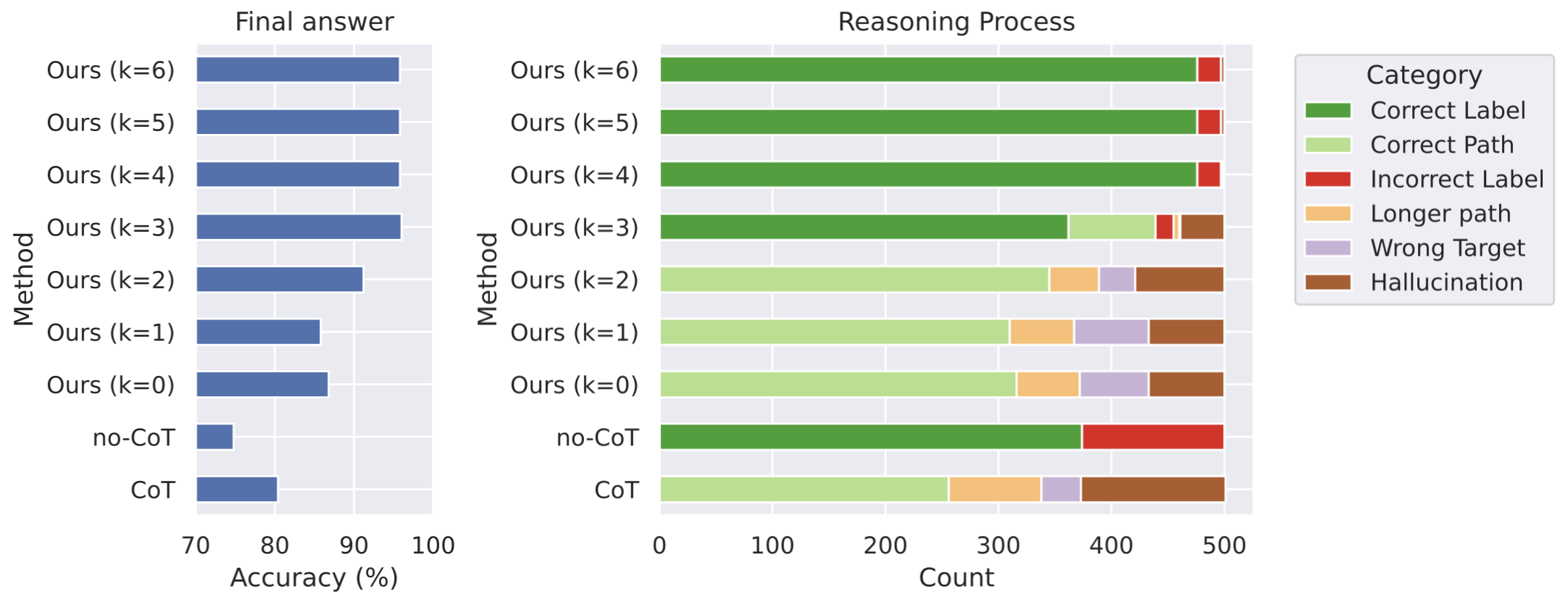

Metrics. We apply two sets of evaluation metrics. One of them is based on the correctness of the final answer, regardless of the reasoning process. It is also the main metric used in the later sections (Section [@sec:result]). To enable fine-grained analysis on ProsQA, we define another metric on the reasoning process. We classify a reasoning chain into (1) Correct Path: The output is one of the shortest paths to the correct answer. (2) Longer Path: A valid path that correctly answers the question but is longer than the shortest path. (3) Hallucination: The path includes nonexistent edges or is disconnected. (4) Wrong Target: A valid path in the graph, but the destination node is not the one being asked. These four categories naturally apply to the output from COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT (k=0k=0k=0) and CoT, which generate the full path. For COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT with k>0k>0k>0 that outputs only partial paths in language (with the initial steps in continuous reasoning), we classify the reasoning as a Correct Path if a valid explanation can complete it. Also, we define Longer Path and Wrong Target for partial paths similarly. If no valid explanation completes the path, it's classified as Hallucination. In no-CoT and COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT with larger kkk, the model may only output the final answer without any partial path, and it falls into (5) Correct Label or (6) Incorrect Label. These six categories cover all cases without overlap.

4.2 Overall Results

Figure 3 presents a comparative analysis of various reasoning methods evaluated on ProsQA. The model trained using CoT frequently hallucinates non-existent edges or outputs paths leading to incorrect targets, resulting in lower answer accuracy. In contrast, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT , which leverages continuous space reasoning, demonstrates improved accuracy as it utilizes an increasing number of continuous thoughts. Additionally, the rate of correct reasoning processes (indicated by "Correct Label" and "Correct Path") significantly increases. At the same time, there is a notable reduction in instances of "Hallucination" and "Wrong Target," issues that typically emerge when the model makes mistakes early in the reasoning process.

An intuitive demonstration of the limitations of reasoning in language space is provided by the case study depicted in Figure [@fig:interpret]. As shown, models operating in language space often fail to plan ahead or backtrack. Once they commit to an incorrect path, they either hallucinate unsupported edges or terminate with irrelevant conclusions. In contrast, latent reasoning avoids such premature commitments by enabling the model to iteratively refine its decisions across multiple reasoning steps. This flexibility allows the model to progressively eliminate incorrect options and converge on the correct answer, ultimately resulting in higher accuracy.

4.3 Interpreting the Latent Reasoning as Tree Search

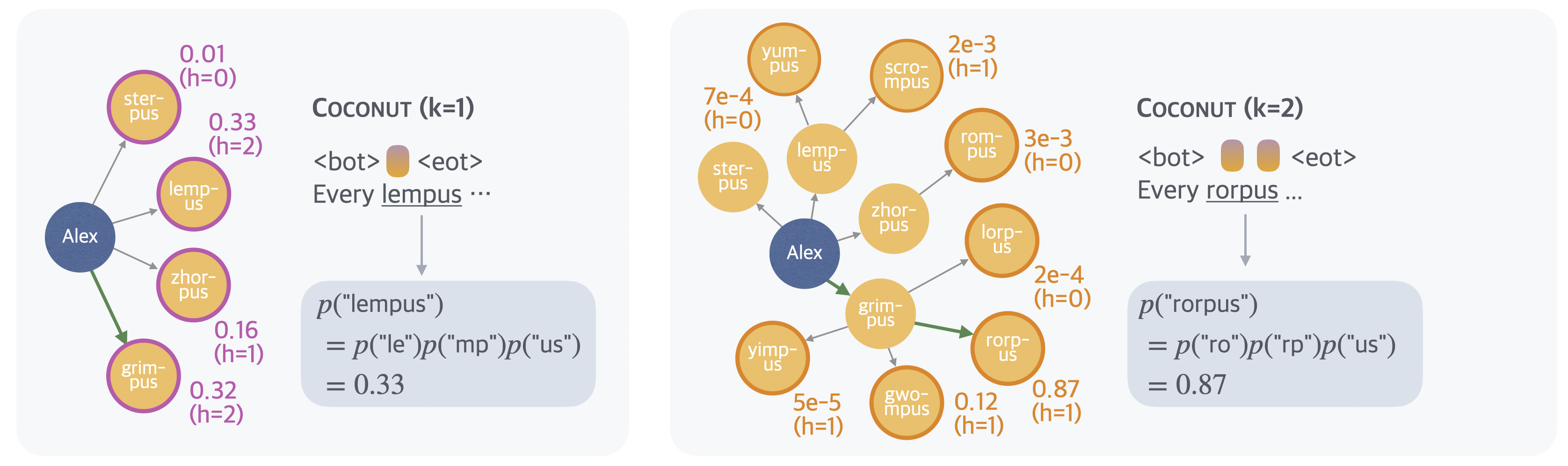

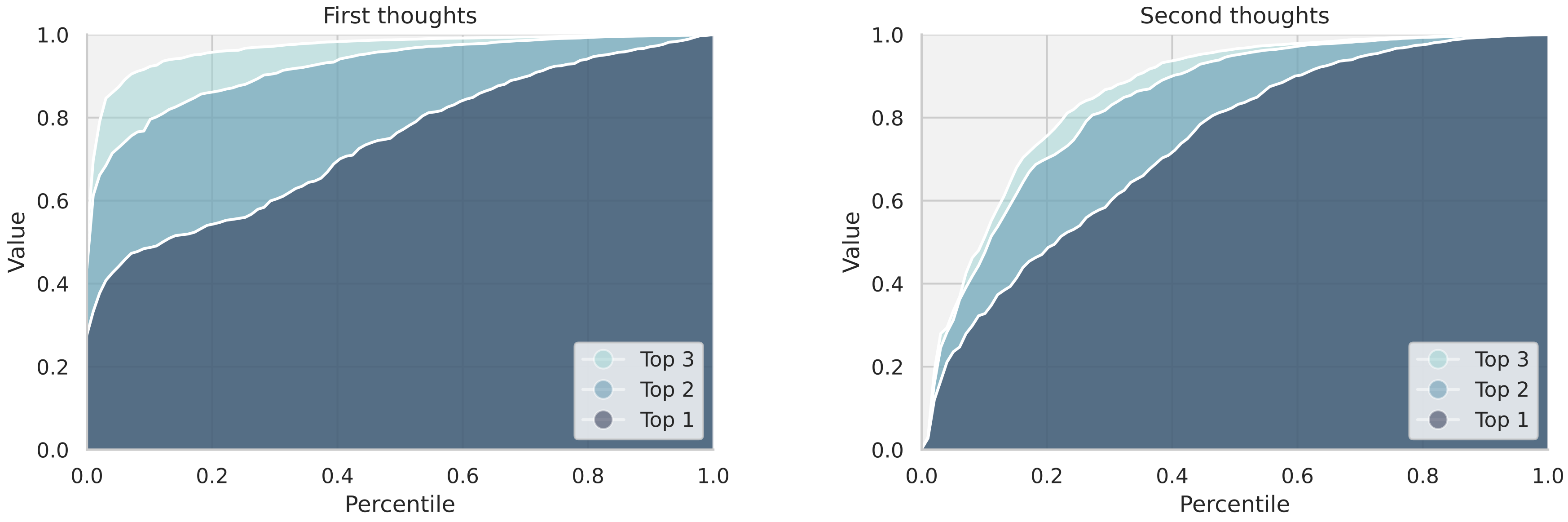

To better understand COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT , we probe the latent reasoning process by forcing the model to explicitly generate language reasoning steps following intermediate continuous thoughts (Figure 5). Using the example presented in Figure [@fig:interpret], at the initial reasoning step, the model must select which immediate child node of "Alex" to consider next, specifically from the set "lempus", "sterpus", "zhorpus", "grimpus". The distribution over these candidate next steps is visualized in Figure~[@fig:height], left. In the subsequent reasoning step, these nodes expand further into an extended set of potential paths, including all grandchildren of "Alex" (Figure [@fig:height], right).

We define the predicted probability of a concept following continuous thoughts as a value function (Figure [@fig:height]), estimating each node's potential for reaching the correct target. Interestingly, the reasoning strategy employed by COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT is not greedy search: while "lempus" initially has the highest value (0.33) at the first reasoning step (Figure~[@fig:height], left), the model subsequently assigns the highest value (0.87) to "rorpus," a child of "grimpus," rather than following "lempus" (Figure [@fig:height], right). This characteristic resembles a breadth-first search (BFS) approach, contrasting sharply with the greedy decoding typical of traditional CoT methods. The inherent capability of continuous representations to encode multiple candidate paths enables the model to avoid making immediate deterministic decisions. Importantly, this tree search pattern is not limited to the illustrated example, but constitutes a fundamental mechanism underlying the consistent improvement observed with larger values of kkk in COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT .

Figure 6 presents an analysis of the parallelism in the model's latent reasoning across the first and second thoughts. For the first thoughts (left panel), the cumulative values of the top-1, top-2, and top-3 candidate nodes are computed and plotted against their respective percentiles across the test set. The noticeable gaps between the three lines indicate that the model maintains significant diversity in its reasoning paths at this stage, suggesting a broad exploration of alternative possibilities. In contrast, the second thoughts (right panel) show a narrowing of these gaps. This trend suggests that the model transitions from parallel exploration to more focused reasoning in the second latent reasoning step, likely as it gains more certainty about the most promising paths.

4.4 Why is Latent Space Better for Planning?

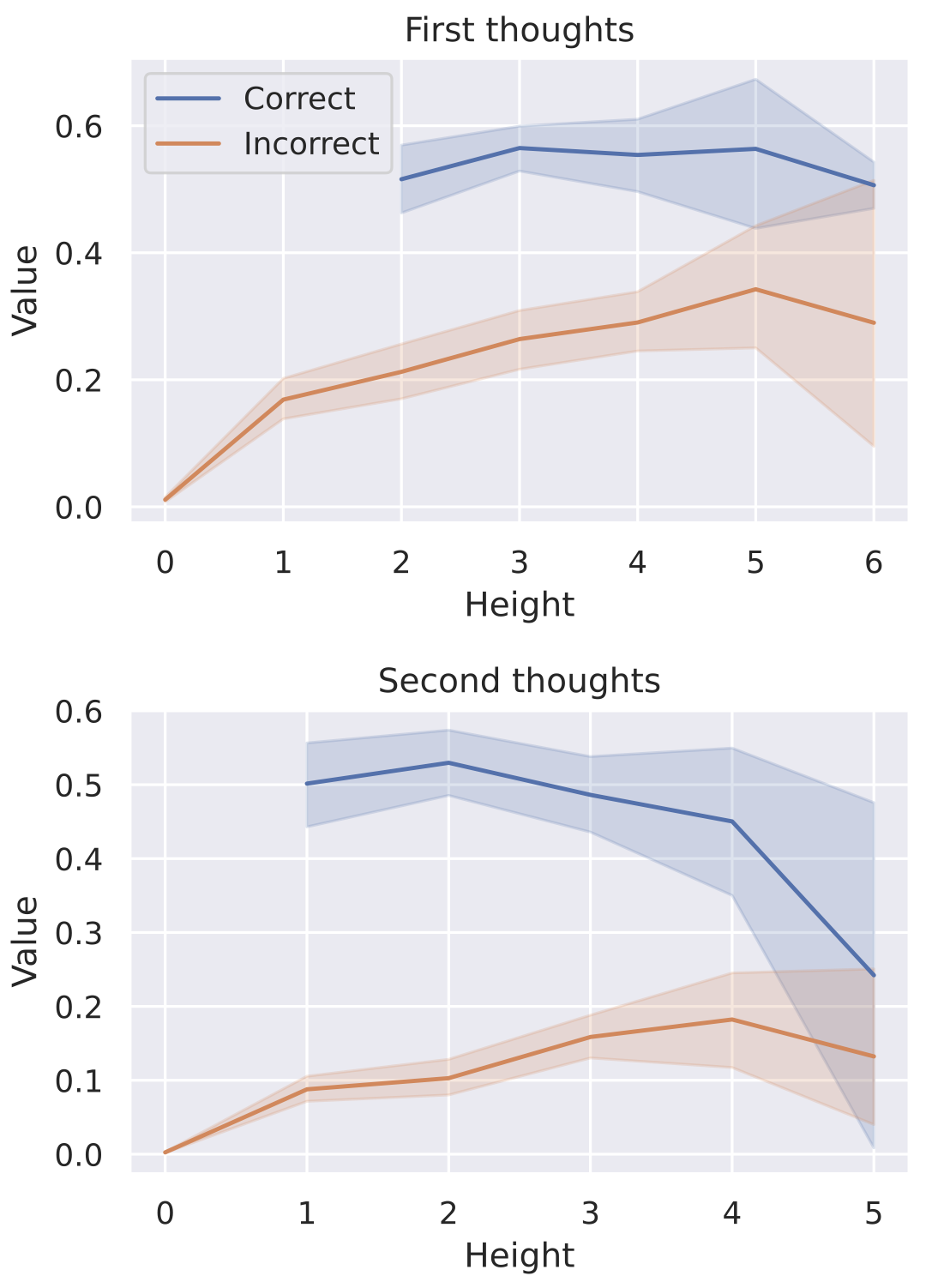

Building upon the tree search perspective, we further examine why latent reasoning benefits planning tasks—specifically, why maintaining multiple candidate paths and postponing deterministic decisions enhances reasoning performance. Our hypothesis is that nodes explored in the early reasoning stages are inherently more challenging to evaluate accurately because they are farther from the final target nodes. In contrast, nodes positioned closer to potential targets, having fewer subsequent exploration possibilities, can be assessed accurately with higher confidence.

To systematically test this, we define the height of a node as its shortest distance to any leaf node and analyze the relationship between node height and the model's estimated value. Ideally, a correct node—one that can lead to the target node—should receive a high estimated value, whereas an incorrect node—one that cannot lead to the target node—should receive a low value. Empirical results across the test set (Figure 7) support our hypothesis: nodes with lower heights consistently receive more accurate and definitive probability evaluations. Conversely, nodes with greater heights exhibit more ambiguous evaluations, reflecting increased uncertainty.

These findings underscore the advantage of latent space reasoning. By delaying deterministic decisions and allowing exploration to proceed toward terminal states, latent reasoning significantly enhances the model’s ability to differentiate correct paths from incorrect ones, thereby improving performance on complex, planning-intensive tasks compared to traditional greedy methods.

5. Empirical Results with COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT

In this section, the authors provide supplementary details about the datasets, efficiency metrics, and extended experiments for COCONUT. They describe three datasets—GSM8k, ProntoQA, and ProsQA—with ProsQA being newly constructed through a directed acyclic graph method that ensures moderately complex reasoning paths between entities and concepts. Clock-time measurements on an Nvidia A100 GPU confirm that inference time correlates with token generation, with COCONUT demonstrating faster inference than traditional chain-of-thought while maintaining competitive accuracy. Experiments with larger models (Llama 3.2-3B and Llama 3-8B) show consistent performance gains over no-CoT baselines, though improvements are less pronounced than with GPT-2, likely because extensive language-focused pre-training makes transitioning to latent reasoning more challenging. The authors acknowledge that surpassing language-based chain-of-thought universally will require dedicated latent space pre-training research, pointing to recent advances in latent representation learning as promising future directions for integrating with COCONUT's reasoning framework.

After analyzing the promising parallel search pattern of COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT , we validate the feasibility of LLM reasoning in a continuous latent space through more comprehensive experiments, highlighting its better reasoning efficiency over language space, as well as its potential to enhance the model's expressivity with test-time scaling.

5.1 Experimental Setup

Math Reasoning. We use GSM8k [15] as the dataset for math reasoning. It consists of grade school-level math problems. To train the model, we use a synthetic dataset generated by [45]. We use two continuous thoughts for each reasoning step (i.e., c=2c=2c=2). The model goes through 3 stages besides the initial stage. We then include an additional stage where still 3×c3\times c3×c continuous thoughts are used as in the previous stage, but with all the remaining language reasoning chain removed. This handles the long-tail distribution of reasoning chains longer than 3 steps. We train the model for 6 epochs in the initial stage, and 3 epochs in each remaining stage.

Logical Reasoning. Logical reasoning involves the proper application of known conditions to prove or disprove a conclusion using logical rules. We use the ProntoQA \citep{saparov2022language} dataset, and our newly proposed ProsQA dataset, which is more challenging due to more distracting branches. We use one continuous thought for every reasoning step (i.e., c=1c=1c=1). The model goes through 6 training stages in addition to the initial stage, because the maximum number of reasoning steps is 6 in these two datasets. The model then fully reasons with continuous thoughts to solve the problems in the last stage. We train the model for 5 epochs per stage.

For all datasets, after the standard schedule, the model stays in the final training stage, until reaching 50 epochs. We select the checkpoint based on the accuracy on the validation set. For inference, we manually set the number of continuous thoughts to be consistent with their final training stage. We use greedy decoding for all experiments.

5.2 Baselines and Variants of COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT

We consider the following baselines: (1) CoT, and (2) No-CoT, which were introduced in Section 4. (3) iCoT \citep{deng2024explicit}: The model is trained with language reasoning chains and follows a carefully designed schedule that "internalizes" CoT. As the training goes on, tokens at the beginning of the reasoning chain are gradually removed until only the answer remains. During inference, the model directly predicts the answer. (4) Pause token [39]: The model is trained using only the question and answer without a reasoning chain. However, different from No-CoT, special <pause> tokens are inserted between the question and answer, which provides the model with additional computational capacity to derive the answer. The number of <pause> tokens is set the same as continuous thoughts in COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT .

We also evaluate some variants of COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT : (1) w/o curriculum, which directly trains the model in the last stage. The model uses continuous thoughts to solve the whole problem. (2) w/o thought: We keep the multi-stage training, but don't add any continuous latent thoughts. While this is similar to iCoT in the high-level idea, the exact training schedule is set to be consistent with COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT , instead of iCoT, for a strict comparison. (3) Pause as thought: We use special <pause> tokens to replace the continuous thoughts, and apply the same multi-stage training curriculum as COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT .

5.3 Results and Discussion

We show the overall results in Table \ref{tab:main}. Using continuous thoughts effectively enhances LLM reasoning over the No-CoT baseline. For example, by using 6 continuous thoughts, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT achieves 34.1% accuracy on GSM8k, which significantly outperforms No-CoT (16.5%). We highlight several key findings below.

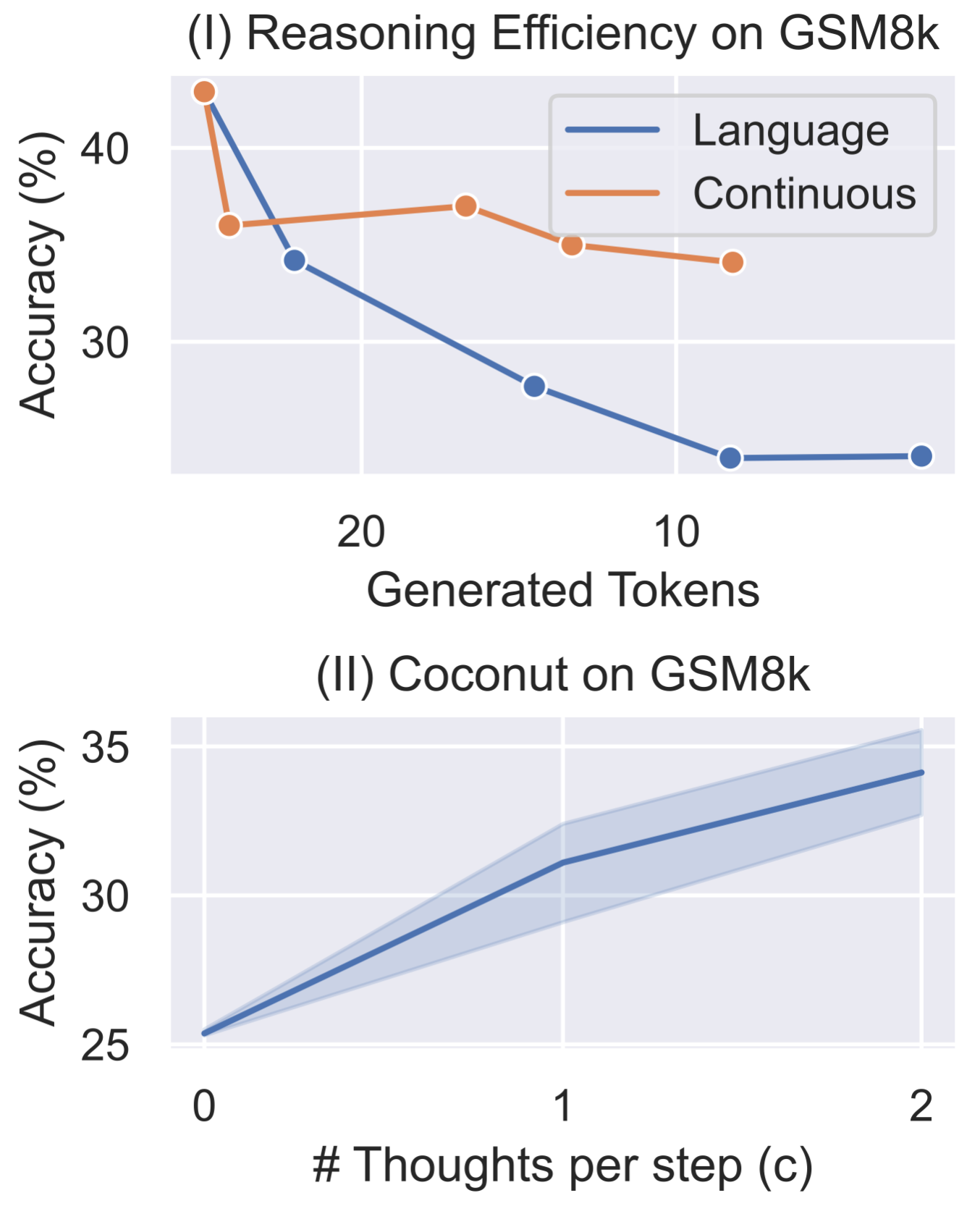

"Chaining" continuous thoughts enhances reasoning. Language CoT proves to increase the effective depth of LLMs and enhance their expressiveness [26]. Thus, generating more tokens serves as a way to inference-time scaling for reasoning [52, 53]. This desirable property holds naturally for COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT too. On GSM8k, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT outperformed other architectures trained with similar strategies, including COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT (pause as thought) and COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT (w/o thought). Particularly, it surpasses the latest baseline iCoT [12], which requires a more carefully designed training schedule.

Additionally, we experimented with adjusting the hyperparameter ccc, which controls the number of latent thoughts corresponding to one language reasoning step (Figure 8, II). As we increased ccc from 0 to 1 to 2, the model's performance steadily improved. This further validates the potential of continuous thoughts to scale up to harder problems. In two other synthetic tasks, we found that the variants of COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT (w/o thoughts or pause as thought), and the iCoT baseline also achieve impressive accuracy. This indicates that the model's computational capacity may not be the bottleneck in these tasks. In contrast, GSM8k involves more complex contextual understanding and modeling, placing higher demands on computational capability.

Continuous thoughts are efficient representations of reasoning. Compared to traditional CoT, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT generates fewer tokens while achieving higher accuracy on ProntoQA and ProsQA (Table \ref{tab:main}). Although COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT does not surpass CoT on GSM8k, it offers a superior trade-off between reasoning efficiency and accuracy (Figure 8, I). To illustrate this, we train a series of CoT models that progressively "internalize"~\citep{deng2024explicit} the initial m={0,1,2,3,ALL}m=\{0, 1, 2, 3, \text{ALL}\}m={0,1,2,3,ALL} reasoning steps, and plot their accuracy versus the number of generated tokens (labeled as "language" in the figure). These models quickly lose accuracy as more reasoning steps are skipped. In contrast, by applying COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT training strategy—replacing each language reasoning step with two continuous thoughts—the accuracy drop is substantially mitigated, maintaining higher performance even when fewer tokens are generated. Another interesting observation is that, when we decode the first continuous thought, it often corresponds to possible intermediate variables in the calculation (Figure 9). This also suggests that the continuous thoughts are more efficient representations of reasoning.

The LLM still needs guidance to learn latent reasoning. In the ideal case, the model should learn the most effective continuous thoughts automatically through gradient descent on questions and answers (i.e., COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT w/o curriculum). However, from the experimental results, we found the models trained this way do not perform any better than no-CoT.

On the contrary, with the multi-stage curriculum, COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT is able to achieve top performance across various tasks. The multi-stage training also integrates well with pause tokens (COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT - pause as thought). Despite using the same architecture and similar multi-stage training objectives, we observed a small gap between the performance of iCoT and COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT (w/o thoughts). The finer-grained removal schedule (token by token) and a few other tricks in iCoT may ease the training process. We leave combining iCoT and COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT as future work. While the multi-stage training used for COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT has proven effective, further research is definitely needed to develop better and more general strategies for learning reasoning in latent space, especially without the supervision from language reasoning chains.

6. Conclusion

In this section, the authors introduce Coconut, a novel approach that enables large language models to reason in continuous latent space rather than through explicit language-based chain-of-thought. This paradigm shift addresses the limitations of traditional sequential reasoning by allowing the model to maintain multiple candidate paths simultaneously through continuous thought representations. The key finding is that latent space reasoning exhibits breadth-first search behavior, exploring alternative reasoning trajectories in parallel instead of committing prematurely to single deterministic paths as language-based methods do. Experimental results across various reasoning tasks confirm that Coconut effectively improves model performance through this emergent parallel exploration capability. The authors acknowledge that further work is required to scale latent reasoning to pretraining stages for broader generalization, but express optimism that their findings will catalyze continued investigation into latent reasoning mechanisms, ultimately contributing to the development of more sophisticated and capable machine reasoning systems.

In this paper, we introduce COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT , a new paradigm for reasoning in continuous latent space. Experiments demonstrate that COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT effectively enhances LLM performance across a variety of reasoning tasks. Reasoning in latent space gives rise to advanced emergent behaviors, where continuous thoughts can represent multiple alternative next steps. This enables the model to perform BFS over possible reasoning paths, rather than prematurely committing to a single deterministic trajectory as in language space CoT reasoning. Further research is needed to refine and scale latent reasoning to pretraining, which could improve generalization across a broader range of reasoning challenges. We hope our findings will spark continued exploration into latent reasoning, ultimately advancing the development of more capable machine reasoning systems.

Acknowledgement

In this section, the authors acknowledge the contribution of Jihoon Tack, expressing sincere gratitude for his valuable discussions that supported the development of this work throughout its course.

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Jihoon Tack for his valuable discussions throughout the course of this work.

References

In this section, the references catalog a diverse body of recent work spanning large language model development, reasoning architectures, mathematical problem-solving, and cognitive neuroscience foundations that inform the paper's approach to latent reasoning. The citations establish the landscape of chain-of-thought prompting and its limitations, pointing to greedy reasoning behaviors and the challenge of computational efficiency in traditional language-based methods. They document foundational models like Llama and GPT-4, alternative reasoning frameworks including tree-of-thoughts and modular prompting, and specialized mathematical reasoning datasets and training methods. Neuroscience research on language-independent reasoning networks provides biological motivation for non-linguistic thought processes. The references also cover emerging paradigms like pause tokens, internalized reasoning, test-time compute scaling, and energy-based transformers, collectively supporting the premise that moving reasoning from discrete language space to continuous latent space can enable more efficient, parallel exploration of solution paths while maintaining or improving accuracy on complex reasoning tasks.

[1] Abhimanyu Dubey, Abhinav Jauhri, Abhinav Pandey, Abhishek Kadian, Ahmad Al-Dahle, Aiesha Letman, Akhil Mathur, Alan Schelten, Amy Yang, Angela Fan, et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783, 2024.

[2] Josh Achiam, Steven Adler, Sandhini Agarwal, Lama Ahmad, Ilge Akkaya, Florencia Leoni Aleman, Diogo Almeida, Janko Altenschmidt, Sam Altman, Shyamal Anadkat, et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

[3] Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Fei Xia, Ed Chi, Quoc V Le, Denny Zhou, et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35:24824–24837, 2022.

[4] Marie Amalric and Stanislas Dehaene. A distinct cortical network for mathematical knowledge in the human brain. NeuroImage, 189:19–31, 2019.

[5] Martin M Monti, Lawrence M Parsons, and Daniel N Osherson. Thought beyond language: neural dissociation of algebra and natural language. Psychological science, 23(8):914–922, 2012.

[6] Martin M Monti, Daniel N Osherson, Michael J Martinez, and Lawrence M Parsons. Functional neuroanatomy of deductive inference: a language-independent distributed network. Neuroimage, 37(3):1005–1016, 2007.

[7] Martin M Monti, Lawrence M Parsons, and Daniel N Osherson. The boundaries of language and thought in deductive inference. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(30):12554–12559, 2009.

[8] Evelina Fedorenko, Michael K Behr, and Nancy Kanwisher. Functional specificity for high-level linguistic processing in the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(39):16428–16433, 2011.

[9] Evelina Fedorenko, Steven T Piantadosi, and Edward AF Gibson. Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought. Nature, 630(8017):575–586, 2024.

[10] Aman Madaan and Amir Yazdanbakhsh. Text and patterns: For effective chain of thought, it takes two to tango. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.07686, 2022.

[11] Eric Zelikman, Georges Harik, Yijia Shao, Varuna Jayasiri, Nick Haber, and Noah D Goodman. Quiet-star: Language models can teach themselves to think before speaking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09629, 2024.

[12] Yuntian Deng, Yejin Choi, and Stuart Shieber. From explicit cot to implicit cot: Learning to internalize cot step by step. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14838, 2024.

[13] Shunyu Yao, Dian Yu, Jeffrey Zhao, Izhak Shafran, Tom Griffiths, Yuan Cao, and Karthik Narasimhan. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2023.

[14] Shibo Hao, Yi Gu, Haodi Ma, Joshua Jiahua Hong, Zhen Wang, Daisy Zhe Wang, and Zhiting Hu. Reasoning with language model is planning with world model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14992, 2023.

[15] Karl Cobbe, Vineet Kosaraju, Mohammad Bavarian, Mark Chen, Heewoo Jun, Lukasz Kaiser, Matthias Plappert, Jerry Tworek, Jacob Hilton, Reiichiro Nakano, et al. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168, 2021.

[16] Abulhair Saparov and He He. Language models are greedy reasoners: A systematic formal analysis of chain-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.01240, 2022.

[17] Lucas Lehnert, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, Paul Mcvay, Michael Rabbat, and Yuandong Tian. Beyond a*: Better planning with transformers via search dynamics bootstrapping. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.14083, 2024.

[18] Tushar Khot, Harsh Trivedi, Matthew Finlayson, Yao Fu, Kyle Richardson, Peter Clark, and Ashish Sabharwal. Decomposed prompting: A modular approach for solving complex tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.02406, 2022.

[19] Denny Zhou, Nathanael Schärli, Le Hou, Jason Wei, Nathan Scales, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Claire Cui, Olivier Bousquet, Quoc Le, et al. Least-to-most prompting enables complex reasoning in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.10625, 2022.

[20] Xiang Yue, Xingwei Qu, Ge Zhang, Yao Fu, Wenhao Huang, Huan Sun, Yu Su, and Wenhu Chen. Mammoth: Building math generalist models through hybrid instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.05653, 2023.

[21] Longhui Yu, Weisen Jiang, Han Shi, Jincheng Yu, Zhengying Liu, Yu Zhang, James T Kwok, Zhenguo Li, Adrian Weller, and Weiyang Liu. Metamath: Bootstrap your own mathematical questions for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.12284, 2023.

[22] Peiyi Wang, Lei Li, Zhihong Shao, Runxin Xu, Damai Dai, Yifei Li, Deli Chen, Yu Wu, and Zhifang Sui. Math-shepherd: Verify and reinforce llms step-by-step without human annotations. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 9426–9439, 2024.

[23] Alex Havrilla, Yuqing Du, Sharath Chandra Raparthy, Christoforos Nalmpantis, Jane Dwivedi-Yu, Maksym Zhuravinskyi, Eric Hambro, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, and Roberta Raileanu. Teaching large language models to reason with reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.04642, 2024.

[24] Zhihong Shao, Peiyi Wang, Qihao Zhu, Runxin Xu, Junxiao Song, Mingchuan Zhang, YK Li, Yu Wu, and Daya Guo. Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03300, 2024.

[25] Fangxu Yu, Lai Jiang, Haoqiang Kang, Shibo Hao, and Lianhui Qin. Flow of reasoning: Efficient training of llm policy with divergent thinking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05673, 2024a.

[26] Guhao Feng, Bohang Zhang, Yuntian Gu, Haotian Ye, Di He, and Liwei Wang. Towards revealing the mystery behind chain of thought: a theoretical perspective. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2023.

[27] William Merrill and Ashish Sabharwal. The expresssive power of transformers with chain of thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07923, 2023.

[28] Zhiyuan Li, Hong Liu, Denny Zhou, and Tengyu Ma. Chain of thought empowers transformers to solve inherently serial problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12875, 2024.

[29] Yann LeCun. A path towards autonomous machine intelligence version 0.9. 2, 2022-06-27. Open Review, 62(1):1–62, 2022.

[30] Yuxi Xie, Kenji Kawaguchi, Yiran Zhao, James Xu Zhao, Min-Yen Kan, Junxian He, and Michael Xie. Self-evaluation guided beam search for reasoning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2023.

[31] Shibo Hao, Yi Gu, Haotian Luo, Tianyang Liu, Xiyan Shao, Xinyuan Wang, Shuhua Xie, Haodi Ma, Adithya Samavedhi, Qiyue Gao, et al. Llm reasoners: New evaluation, library, and analysis of step-by-step reasoning with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.05221, 2024.

[32] Kanishk Gandhi, Denise Lee, Gabriel Grand, Muxin Liu, Winson Cheng, Archit Sharma, and Noah D Goodman. Stream of search (sos): Learning to search in language. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.03683, 2024.

[33] DiJia Su, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, Michael Rabbat, Yuandong Tian, and Qinqing Zheng. Dualformer: Controllable fast and slow thinking by learning with randomized reasoning traces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.09918, 2024.

[34] Sohee Yang, Elena Gribovskaya, Nora Kassner, Mor Geva, and Sebastian Riedel. Do large language models latently perform multi-hop reasoning? arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.16837, 2024.

[35] Eden Biran, Daniela Gottesman, Sohee Yang, Mor Geva, and Amir Globerson. Hopping too late: Exploring the limitations of large language models on multi-hop queries. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12775, 2024.

[36] Yuval Shalev, Amir Feder, and Ariel Goldstein. Distributional reasoning in llms: Parallel reasoning processes in multi-hop reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13858, 2024.

[37] Boshi Wang, Sewon Min, Xiang Deng, Jiaming Shen, You Wu, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Huan Sun. Towards understanding chain-of-thought prompting: An empirical study of what matters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10001, 2022.

[38] Miles Turpin, Julian Michael, Ethan Perez, and Samuel Bowman. Language models don't always say what they think: unfaithful explanations in chain-of-thought prompting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2024.

[39] Sachin Goyal, Ziwei Ji, Ankit Singh Rawat, Aditya Krishna Menon, Sanjiv Kumar, and Vaishnavh Nagarajan. Think before you speak: Training language models with pause tokens. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02226, 2023.

[40] Jacob Pfau, William Merrill, and Samuel Bowman. Let's think dot by dot: Hidden computation in transformer language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15758, 2024.

[41] Jonas Geiping, Sean McLeish, Neel Jain, John Kirchenbauer, Siddharth Singh, Brian R Bartoldson, Bhavya Kailkhura, Abhinav Bhatele, and Tom Goldstein. Scaling up test-time compute with latent reasoning: A recurrent depth approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.05171, 2025.

[42] Lo"ıc Barrault, Paul-Ambroise Duquenne, Maha Elbayad, Artyom Kozhevnikov, Belen Alastruey, Pierre Andrews, Mariano Coria, Guillaume Couairon, Marta R Costa-jussà, David Dale, et al. Large concept models: Language modeling in a sentence representation space. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.08821, 2024.

[43] Alexi Gladstone, Ganesh Nanduru, Md Mofijul Islam, Peixuan Han, Hyeonjeong Ha, Aman Chadha, Yilun Du, Heng Ji, Jundong Li, and Tariq Iqbal. Energy-based transformers are scalable learners and thinkers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.02092, 2025.

Appendix

A. Datasets

A.1 Examples

We provide some examples of the questions and CoT solutions for the datasets used in our experiments.

A.2 Construction of ProsQA

To construct the dataset, we first compile a set of typical entity names, such as “Alex” and “Jack,” along with fictional concept names like “lorpus” and “rorpus,” following the setting of ProntoQA [16]. Each problem is structured as a binary question: “Is [Entity] a [Concept A] or [Concept B]?” Assuming [Concept A] is the correct answer, we build a directed acyclic graph (DAG) where each node represents an entity or a concept. The graph is constructed such that a path exists from [Entity] to [Concept A] but not to [Concept B]. Algorithm 1 describes the graph construction process. The DAG is incrementally built by adding nodes and randomly connecting them with edges. To preserve the validity of the binary choice, with some probability, we enforce that the new node cannot simultaneously serve as a descendant to both node 000 and 111. This separation maintains distinct families of nodes and balances their sizes to prevent model shortcuts. After the graph is constructed, nodes without parents are assigned entity names, while other nodes receive concept names. To formulate a question of the form “Is [Entity] a [Concept A] or [Concept B]?”, we designate node 000 in the graph as [Entity], a leaf node labeled 111 as [Concept A], and a leaf node labeled 222 as [Concept B]. This setup ensures a path from [Entity] to [Concept A] without any connection to [Concept B], introducing a moderately complex reasoning path. Finally, to avoid positional biases, [Concept A] and [Concept B] are randomly permuted in each question.

Algorithm 1: Graph Construction for ProsQA

edges←{}edges \gets \{\}edges←{}

nodes←{0,1}nodes \gets \{0, 1\}nodes←{0,1}

labels←{0:1,1:2}labels \gets \{0: 1, 1:2\}labels←{0:1,1:2} ▹\triangleright▹ Labels: 1 (descendant of node 0), 2 (descendant of node 1), 3 (both), 0 (neither).

groups←{0:{},1:{0},2:{1},3:{}}groups \gets \{0: \{\}, 1: \{0\}, 2: \{1\}, 3: \{\}\}groups←{0:{},1:{0},2:{1},3:{}}

idx←2idx \gets 2idx←2

while idx<Nidx < Nidx<N do ▹\triangleright▹ For each new node, randomly add edges from existing nodes

n_in_nodes←poisson(1.5)n\_in\_nodes \gets \text{poisson}(1.5)n_in_nodes←poisson(1.5)

rand←random()rand \gets \text{random}()rand←random()

if rand≤0.35rand \le 0.35rand≤0.35 then

candidates←groups[0]∪groups[1]candidates \gets groups[0] \cup groups[1]candidates←groups[0]∪groups[1] ▹\triangleright▹ Cannot be a descendant of node 1.

else if rand≤0.7rand \le 0.7rand≤0.7 then

candidates←groups[0]∪groups[2]candidates \gets groups[0] \cup groups[2]candidates←groups[0]∪groups[2] ▹\triangleright▹ Cannot be a descendant of node 0.

else

candidates←nodescandidates \gets nodescandidates←nodes

end if

n_in_nodes←min(len(candidates),n_in_nodes)n\_in\_nodes \gets \min(\text{len}(candidates), n\_in\_nodes)n_in_nodes←min(len(candidates),n_in_nodes)

weights←[depth_to_root(c)⋅1.5+1 ∀c∈candidates]weights \gets [\text{depth\_to\_root}(c) \cdot 1.5 + 1 \;\forall c \in candidates]weights←[depth_to_root(c)⋅1.5+1∀c∈candidates] ▹\triangleright▹ Define sampling weights to prioritize deeper nodes.

▹\triangleright▹ This way, the solution reasoning chain is expected to be longer.

in_nodes←random_choice(candidates,n_in_nodes,prob=weights/sum(weights))in\_nodes \gets \text{random\_choice}(candidates, n\_in\_nodes, \text{prob} = weights / \text{sum}(weights))in_nodes←random_choice(candidates,n_in_nodes,prob=weights/sum(weights))

cur_label←0cur\_label \gets 0cur_label←0

for in_idx∈in_nodesin\_idx \in in\_nodesin_idx∈in_nodes do

cur_label←cur_label∣labels[in_idx]cur\_label \gets cur\_label \mid labels[in\_idx]cur_label←cur_label∣labels[in_idx] ▹\triangleright▹ Update label using bitwise OR.

edges.append((in_idx,idx))edges.\text{append}((in\_idx, idx))edges.append((in_idx,idx))

end for

groups[cur_label].append(idx)groups[cur\_label].\text{append}(idx)groups[cur_label].append(idx)

labels[idx]←cur_labellabels[idx] \gets cur\_labellabels[idx]←cur_label

nodes←nodes∪{idx}nodes \gets nodes \cup \{idx\}nodes←nodes∪{idx}

idx←idx+1idx \gets idx + 1idx←idx+1

end while

A.3 Statistics

We show the size of all datasets in Table 3.

B. Clock-Time Reasoning Efficiency Metric

We present a clock-time comparison to evaluate reasoning efficiency. The reported values represent the average inference time per test case (in seconds), with a batch size of 1, measured on an Nvidia A100 GPU. For the no-CoT and CoT baselines, we employ the standard generate method from the transformers library. Our results show that clock time is generally proportional to the number of newly generated tokens, as detailed in Table 4.

C. More Discussion

C.1 Using More Continuous Thoughts

In Figure 8 (II), we present the performance of COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT on GSM8k using c∈{0,1,2}c \in \{0, 1, 2\}c∈{0,1,2}. When experimenting with c=3c=3c=3, we observe a slight performance drop accompanied by increased variance. Analysis of the training logs indicates that adding three continuous thoughts at once – particularly during the final stage transition – leads to a sharp spike in training loss, causing instability. Future work will explore finer-grained schedules, such as incrementally adding continuous thoughts one at a time while removing fewer language tokens, as in iCoT ([12]). Additionally, combining language and latent reasoning—e.g., generating the reasoning skeleton in language and completing the reasoning process in latent space—could provide a promising direction for improving performance and stability.

C.2 COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT with Larger Models

We experimented with COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT on GSM8k using Llama 3.2-3B and Llama 3-8B [1] with c=1 c=1c=1. We train them for 3 epochs in Stage 0, followed by 1 epoch per subsequent stage. The results are shown in Table 3.

:Table 5: Experimental results of applying COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT to larger Llama models. We report performance comparisons between models without CoT reasoning (no-CoT) and our proposed COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT method.

We observe consistent performance gains across both Llama 3.2-3B and Llama 3-8B models compared to the no-CoT baseline, though these improvements are not as pronounced as those previously demonstrated with GPT-2. One possible reason is that larger models have already undergone extensive language-focused pre-training, making the transition to latent reasoning more challenging.

We emphasize that the primary goal of this paper is to highlight the promising attributes of latent-space reasoning and to initiate exploration in this new direction. Universally surpassing language-based CoT likely requires significant research efforts dedicated to latent space pre-training. We are encouraged by recent progress in this area [41, 42, 43]. While these recent models provide scalable methods for latent representation learning, the latent spaces have not yet been explicitly optimized for reasoning. Integrating these recent advancements with COCONUT\text{C{\scriptsize OCONUT}}COCONUT presents an exciting and promising avenue for future research.

Acknowledgement

[1] Abhimanyu Dubey, Abhinav Jauhri, Abhinav Pandey, Abhishek Kadian, Ahmad Al-Dahle, Aiesha Letman, Akhil Mathur, Alan Schelten, Amy Yang, Angela Fan, et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783, 2024.

[2] Josh Achiam, Steven Adler, Sandhini Agarwal, Lama Ahmad, Ilge Akkaya, Florencia Leoni Aleman, Diogo Almeida, Janko Altenschmidt, Sam Altman, Shyamal Anadkat, et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

[3] Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Fei Xia, Ed Chi, Quoc V Le, Denny Zhou, et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35:24824–24837, 2022.

[4] Marie Amalric and Stanislas Dehaene. A distinct cortical network for mathematical knowledge in the human brain. NeuroImage, 189:19–31, 2019.

[5] Martin M Monti, Lawrence M Parsons, and Daniel N Osherson. Thought beyond language: neural dissociation of algebra and natural language. Psychological science, 23(8):914–922, 2012.

[6] Martin M Monti, Daniel N Osherson, Michael J Martinez, and Lawrence M Parsons. Functional neuroanatomy of deductive inference: a language-independent distributed network. Neuroimage, 37(3):1005–1016, 2007.

[7] Martin M Monti, Lawrence M Parsons, and Daniel N Osherson. The boundaries of language and thought in deductive inference. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(30):12554–12559, 2009.

[8] Evelina Fedorenko, Michael K Behr, and Nancy Kanwisher. Functional specificity for high-level linguistic processing in the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(39):16428–16433, 2011.

[9] Evelina Fedorenko, Steven T Piantadosi, and Edward AF Gibson. Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought. Nature, 630(8017):575–586, 2024.

[10] Aman Madaan and Amir Yazdanbakhsh. Text and patterns: For effective chain of thought, it takes two to tango. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.07686, 2022.

[11] Eric Zelikman, Georges Harik, Yijia Shao, Varuna Jayasiri, Nick Haber, and Noah D Goodman. Quiet-star: Language models can teach themselves to think before speaking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09629, 2024.

[12] Yuntian Deng, Yejin Choi, and Stuart Shieber. From explicit cot to implicit cot: Learning to internalize cot step by step. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14838, 2024.

[13] Shunyu Yao, Dian Yu, Jeffrey Zhao, Izhak Shafran, Tom Griffiths, Yuan Cao, and Karthik Narasimhan. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2023.

[14] Shibo Hao, Yi Gu, Haodi Ma, Joshua Jiahua Hong, Zhen Wang, Daisy Zhe Wang, and Zhiting Hu. Reasoning with language model is planning with world model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14992, 2023.

[15] Karl Cobbe, Vineet Kosaraju, Mohammad Bavarian, Mark Chen, Heewoo Jun, Lukasz Kaiser, Matthias Plappert, Jerry Tworek, Jacob Hilton, Reiichiro Nakano, et al. Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168, 2021.

[16] Abulhair Saparov and He He. Language models are greedy reasoners: A systematic formal analysis of chain-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.01240, 2022.

[17] Lucas Lehnert, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, Paul Mcvay, Michael Rabbat, and Yuandong Tian. Beyond a*: Better planning with transformers via search dynamics bootstrapping. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.14083, 2024.

[18] Tushar Khot, Harsh Trivedi, Matthew Finlayson, Yao Fu, Kyle Richardson, Peter Clark, and Ashish Sabharwal. Decomposed prompting: A modular approach for solving complex tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.02406, 2022.

[19] Denny Zhou, Nathanael Schärli, Le Hou, Jason Wei, Nathan Scales, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Claire Cui, Olivier Bousquet, Quoc Le, et al. Least-to-most prompting enables complex reasoning in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.10625, 2022.

[20] Xiang Yue, Xingwei Qu, Ge Zhang, Yao Fu, Wenhao Huang, Huan Sun, Yu Su, and Wenhu Chen. Mammoth: Building math generalist models through hybrid instruction tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.05653, 2023.

[21] Longhui Yu, Weisen Jiang, Han Shi, Jincheng Yu, Zhengying Liu, Yu Zhang, James T Kwok, Zhenguo Li, Adrian Weller, and Weiyang Liu. Metamath: Bootstrap your own mathematical questions for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.12284, 2023.

[22] Peiyi Wang, Lei Li, Zhihong Shao, Runxin Xu, Damai Dai, Yifei Li, Deli Chen, Yu Wu, and Zhifang Sui. Math-shepherd: Verify and reinforce llms step-by-step without human annotations. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 9426–9439, 2024.

[23] Alex Havrilla, Yuqing Du, Sharath Chandra Raparthy, Christoforos Nalmpantis, Jane Dwivedi-Yu, Maksym Zhuravinskyi, Eric Hambro, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, and Roberta Raileanu. Teaching large language models to reason with reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.04642, 2024.

[24] Zhihong Shao, Peiyi Wang, Qihao Zhu, Runxin Xu, Junxiao Song, Mingchuan Zhang, YK Li, Yu Wu, and Daya Guo. Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03300, 2024.

[25] Fangxu Yu, Lai Jiang, Haoqiang Kang, Shibo Hao, and Lianhui Qin. Flow of reasoning: Efficient training of llm policy with divergent thinking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05673, 2024a.

[26] Guhao Feng, Bohang Zhang, Yuntian Gu, Haotian Ye, Di He, and Liwei Wang. Towards revealing the mystery behind chain of thought: a theoretical perspective. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2023.

[27] William Merrill and Ashish Sabharwal. The expresssive power of transformers with chain of thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07923, 2023.

[28] Zhiyuan Li, Hong Liu, Denny Zhou, and Tengyu Ma. Chain of thought empowers transformers to solve inherently serial problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12875, 2024.

[29] Yann LeCun. A path towards autonomous machine intelligence version 0.9. 2, 2022-06-27. Open Review, 62(1):1–62, 2022.

[30] Yuxi Xie, Kenji Kawaguchi, Yiran Zhao, James Xu Zhao, Min-Yen Kan, Junxian He, and Michael Xie. Self-evaluation guided beam search for reasoning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2023.

[31] Shibo Hao, Yi Gu, Haotian Luo, Tianyang Liu, Xiyan Shao, Xinyuan Wang, Shuhua Xie, Haodi Ma, Adithya Samavedhi, Qiyue Gao, et al. Llm reasoners: New evaluation, library, and analysis of step-by-step reasoning with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.05221, 2024.

[32] Kanishk Gandhi, Denise Lee, Gabriel Grand, Muxin Liu, Winson Cheng, Archit Sharma, and Noah D Goodman. Stream of search (sos): Learning to search in language. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.03683, 2024.

[33] DiJia Su, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, Michael Rabbat, Yuandong Tian, and Qinqing Zheng. Dualformer: Controllable fast and slow thinking by learning with randomized reasoning traces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.09918, 2024.

[34] Sohee Yang, Elena Gribovskaya, Nora Kassner, Mor Geva, and Sebastian Riedel. Do large language models latently perform multi-hop reasoning? arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.16837, 2024.

[35] Eden Biran, Daniela Gottesman, Sohee Yang, Mor Geva, and Amir Globerson. Hopping too late: Exploring the limitations of large language models on multi-hop queries. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.12775, 2024.

[36] Yuval Shalev, Amir Feder, and Ariel Goldstein. Distributional reasoning in llms: Parallel reasoning processes in multi-hop reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13858, 2024.

[37] Boshi Wang, Sewon Min, Xiang Deng, Jiaming Shen, You Wu, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Huan Sun. Towards understanding chain-of-thought prompting: An empirical study of what matters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10001, 2022.

[38] Miles Turpin, Julian Michael, Ethan Perez, and Samuel Bowman. Language models don't always say what they think: unfaithful explanations in chain-of-thought prompting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2024.

[39] Sachin Goyal, Ziwei Ji, Ankit Singh Rawat, Aditya Krishna Menon, Sanjiv Kumar, and Vaishnavh Nagarajan. Think before you speak: Training language models with pause tokens. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02226, 2023.

[40] Jacob Pfau, William Merrill, and Samuel R Bowman. Let's think dot by dot: Hidden computation in transformer language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15758, 2024.

[41] Jonas Geiping, Sean McLeish, Neel Jain, John Kirchenbauer, Siddharth Singh, Brian R Bartoldson, Bhavya Kailkhura, Abhinav Bhatele, and Tom Goldstein. Scaling up test-time compute with latent reasoning: A recurrent depth approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.05171, 2025.

[42] Lo"ıc Barrault, Paul-Ambroise Duquenne, Maha Elbayad, Artyom Kozhevnikov, Belen Alastruey, Pierre Andrews, Mariano Coria, Guillaume Couairon, Marta R Costa-jussà, David Dale, et al. Large concept models: Language modeling in a sentence representation space. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.08821, 2024.

[43] Alexi Gladstone, Ganesh Nanduru, Md Mofijul Islam, Peixuan Han, Hyeonjeong Ha, Aman Chadha, Yilun Du, Heng Ji, Jundong Li, and Tariq Iqbal. Energy-based transformers are scalable learners and thinkers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.02092, 2025.

![**Figure 1:** A comparison of Chain of Continuous Thought ($\textsc{Coconut}$) with Chain-of-Thought (CoT). In CoT, the model generates the reasoning process as a word token sequence (e.g., $[x_{i}, x_{i+1}, ..., x_{i+j}]$ in the figure). $\textsc{Coconut}$ regards the last hidden state as a representation of the reasoning state (termed "continuous thought"), and directly uses it as the next input embedding. This allows the LLM to reason in an unrestricted latent space instead of a language space.](https://ittowtnkqtyixxjxrhou.supabase.co/storage/v1/object/public/public-images/1e0bb66d/figure_1_meta_3.png)