Vision-Language-Action Models: Concepts, Progress, Applications and Challenges

# Executive Summary

Purpose and Context

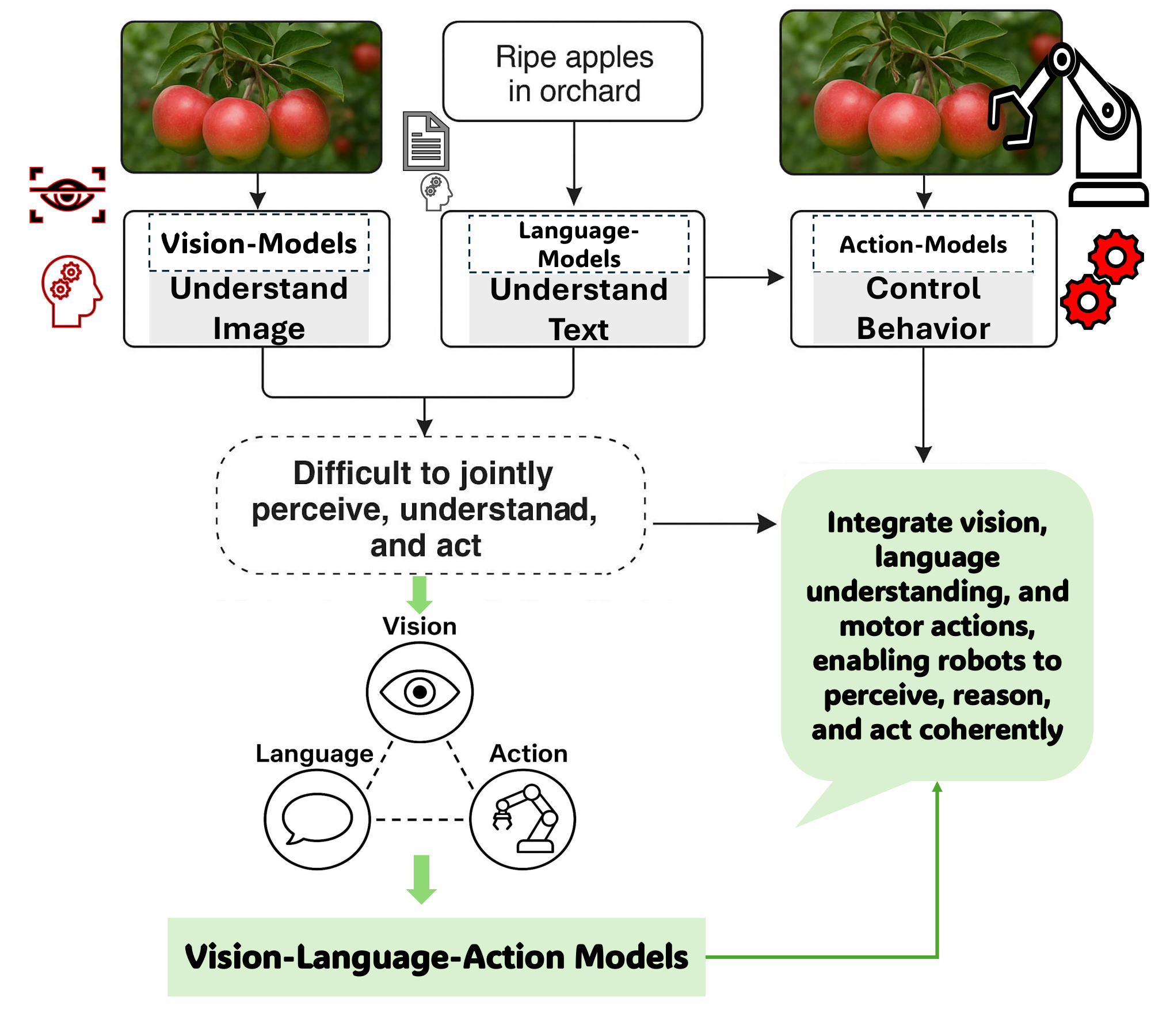

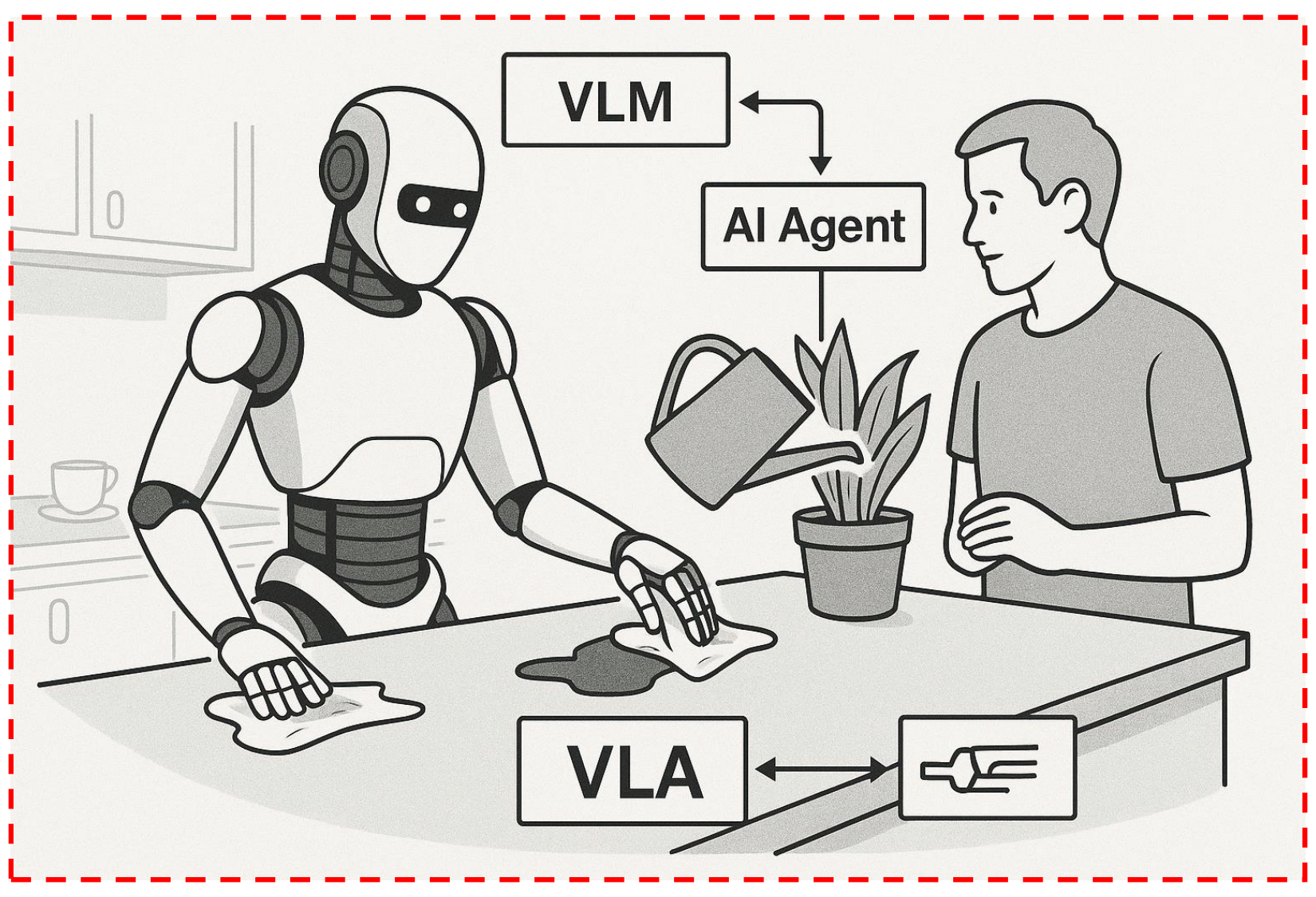

Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models represent a transformative advancement in artificial intelligence, unifying visual perception, natural language understanding, and physical action within a single computational framework. Before VLA models emerged around 2021–2022, robotic and AI systems operated through fragmented pipelines—vision systems could recognize objects, language models could process text, and control systems could execute movements, but these capabilities functioned in isolation. This separation created brittle systems unable to generalize across tasks or adapt to novel environments. VLA models address this limitation by integrating all three modalities into end-to-end learnable architectures, enabling robots and autonomous agents to perceive their surroundings, interpret complex instructions, and execute appropriate actions dynamically. This review consolidates recent progress in VLA research, covering over 80 models published between 2022 and 2025, to provide researchers, engineers, and decision-makers with a comprehensive understanding of the field's current state, applications, and outstanding challenges.

Approach and Methodology

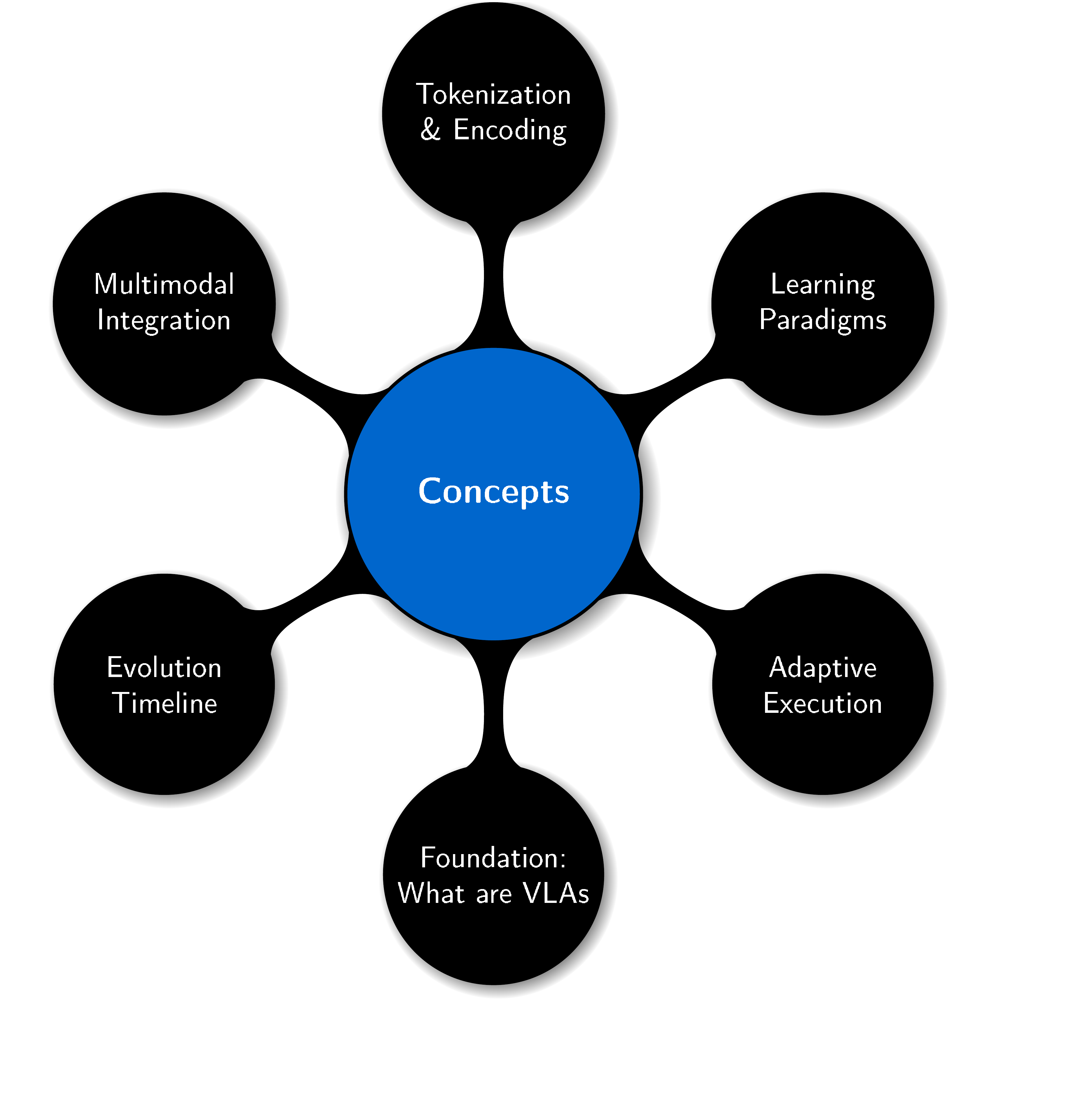

This review adopts a systematic literature analysis framework organized around five thematic pillars: conceptual foundations, architectural progress, training efficiency, real-world applications, and technical challenges. The conceptual foundation section traces VLA evolution from isolated modalities to unified agents, explaining how vision encoders (such as Vision Transformers), language models (such as LLaMA-2 or GPT variants), and action decoders are integrated through token-based representations. These tokens—prefix tokens encoding scene context and instructions, state tokens representing robot configuration, and action tokens specifying motor commands—are processed autoregressively, similar to text generation but producing physical actions instead of words.

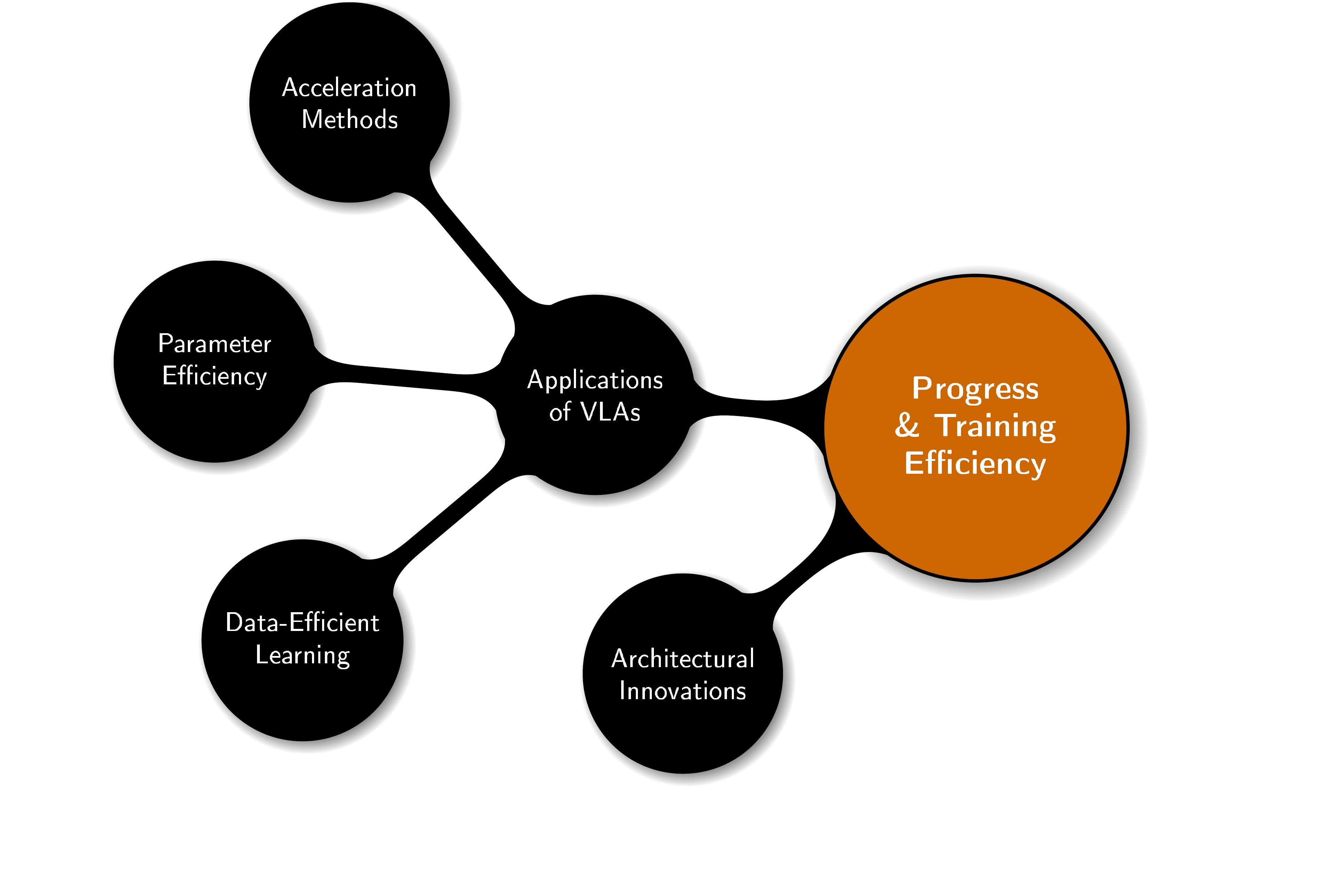

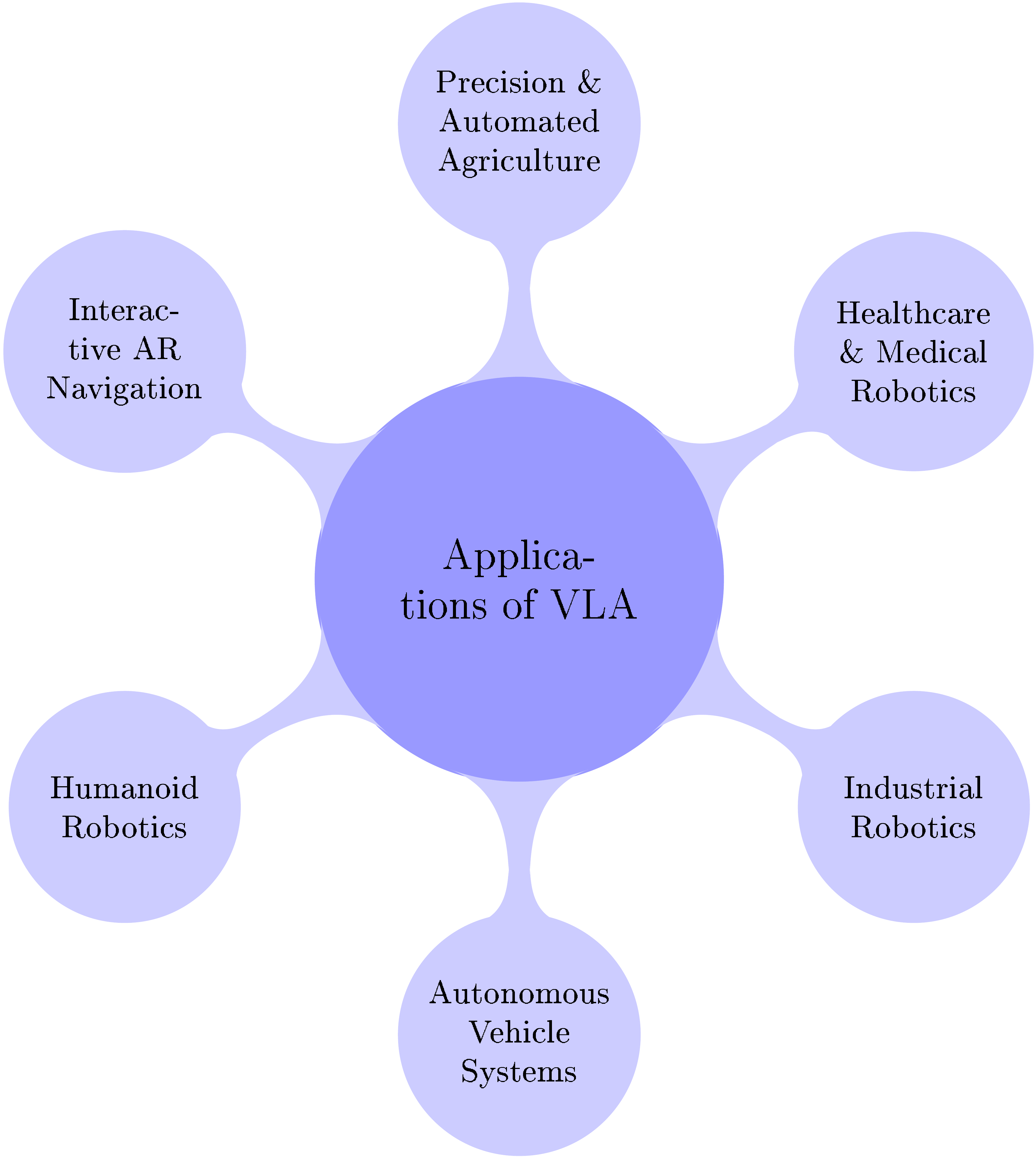

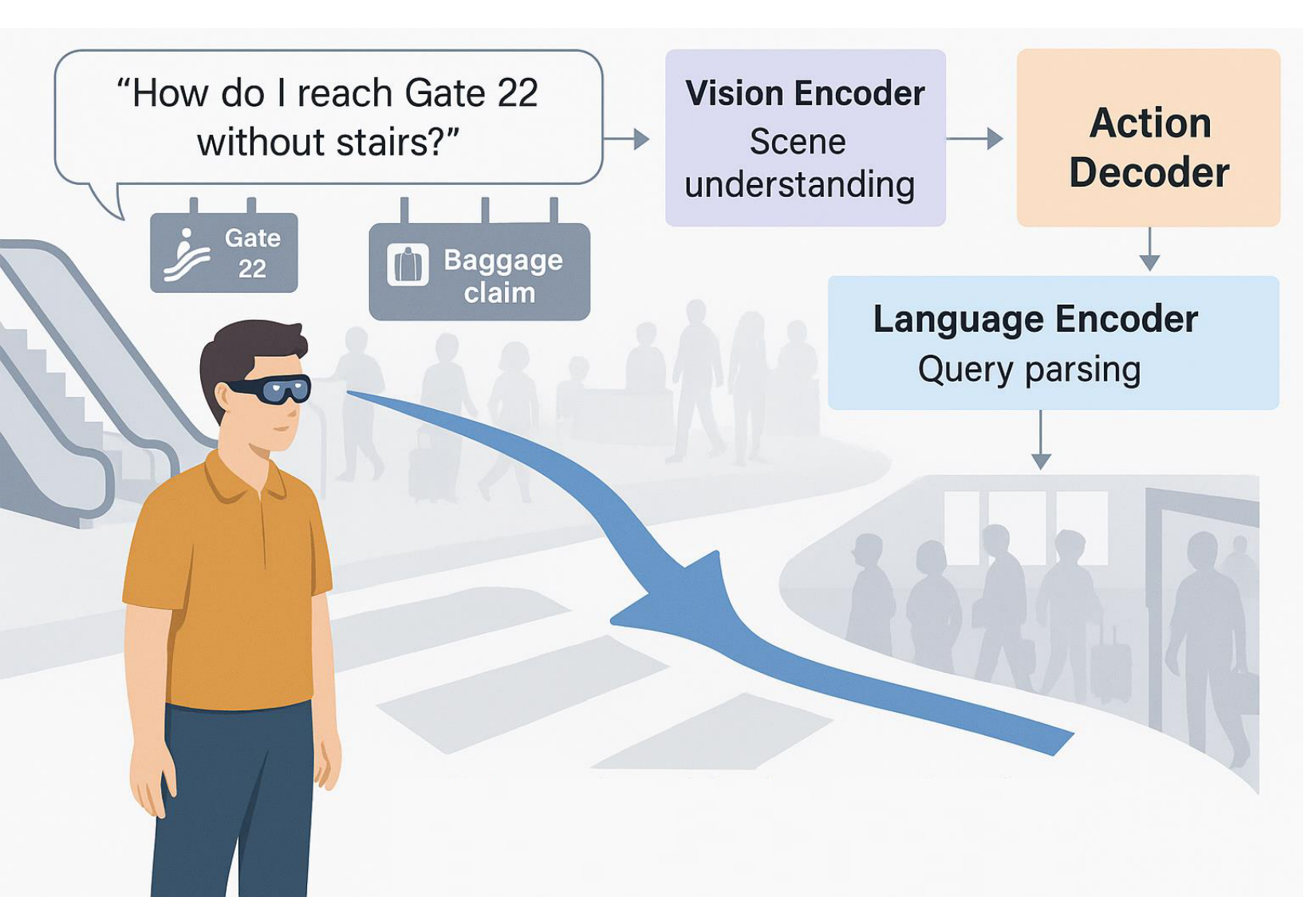

The progress section examines architectural innovations including early fusion models that preserve semantic alignment from pretraining, dual-system architectures separating fast reactive control from slower deliberative planning, and self-correcting frameworks that detect and recover from failures autonomously. Training efficiency strategies are analyzed, including parameter-efficient methods like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA), quantization, model pruning, and inference acceleration techniques such as parallel decoding and compressed action tokenization. The applications section reviews deployment across six domains: humanoid robotics, autonomous vehicles, industrial automation, healthcare and medical robotics, precision agriculture, and augmented reality navigation. The challenges section identifies and categorizes limitations across real-time inference constraints, multimodal action representation, safety assurance, dataset bias, system integration complexity, computational demands, robustness to environmental variability, and ethical deployment considerations.

Main Findings

Architectural maturation: VLA models have evolved through three distinct phases. From 2022–2023, foundational models like CLIPort, RT-1, and VIMA established basic visuomotor coordination through multimodal fusion. In 2024, specialization emerged with domain-specific models incorporating 3D perception, tactile sensing, and memory-efficient architectures. By 2025, current systems prioritize generalization and safety-critical deployment, integrating formal verification, whole-body control for humanoids, and cross-embodiment transfer learning. Models like NVIDIA's Groot N1 demonstrate dual-system architectures combining 10ms-latency diffusion policies for low-level control with LLM-based planners for task decomposition, achieving 17% higher success rates than monolithic models on multi-stage household tasks.

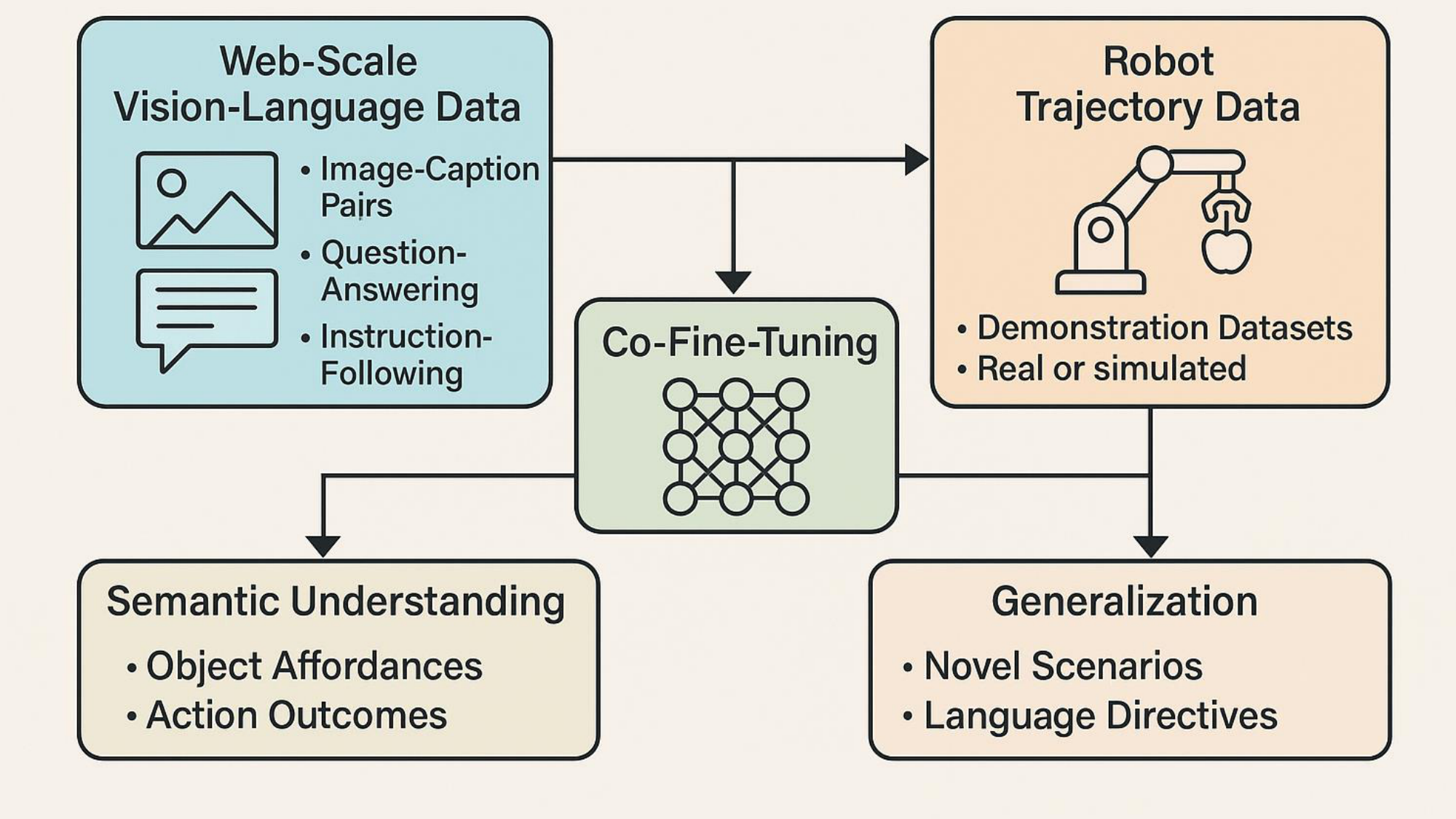

Training efficiency breakthroughs: Co-fine-tuning on web-scale vision-language corpora (LAION-5B) and robotic trajectory datasets (Open X-Embodiment) enables strong generalization with fewer parameters—OpenVLA's 7-billion-parameter model outperforms 55-billion-parameter variants by 16.5% through this approach. Parameter-efficient adaptation via LoRA reduces trainable weights by 70% while maintaining performance, cutting GPU compute time from weeks to under 24 hours on commodity hardware. Quantization to 8-bit integers shrinks models by half with only 3–5% accuracy loss, enabling deployment on edge devices like Jetson platforms. Compressed action tokenization (FAST) achieves 15× faster inference by encoding control sequences as frequency-domain tokens, supporting 200 Hz policy rates critical for dexterous manipulation.

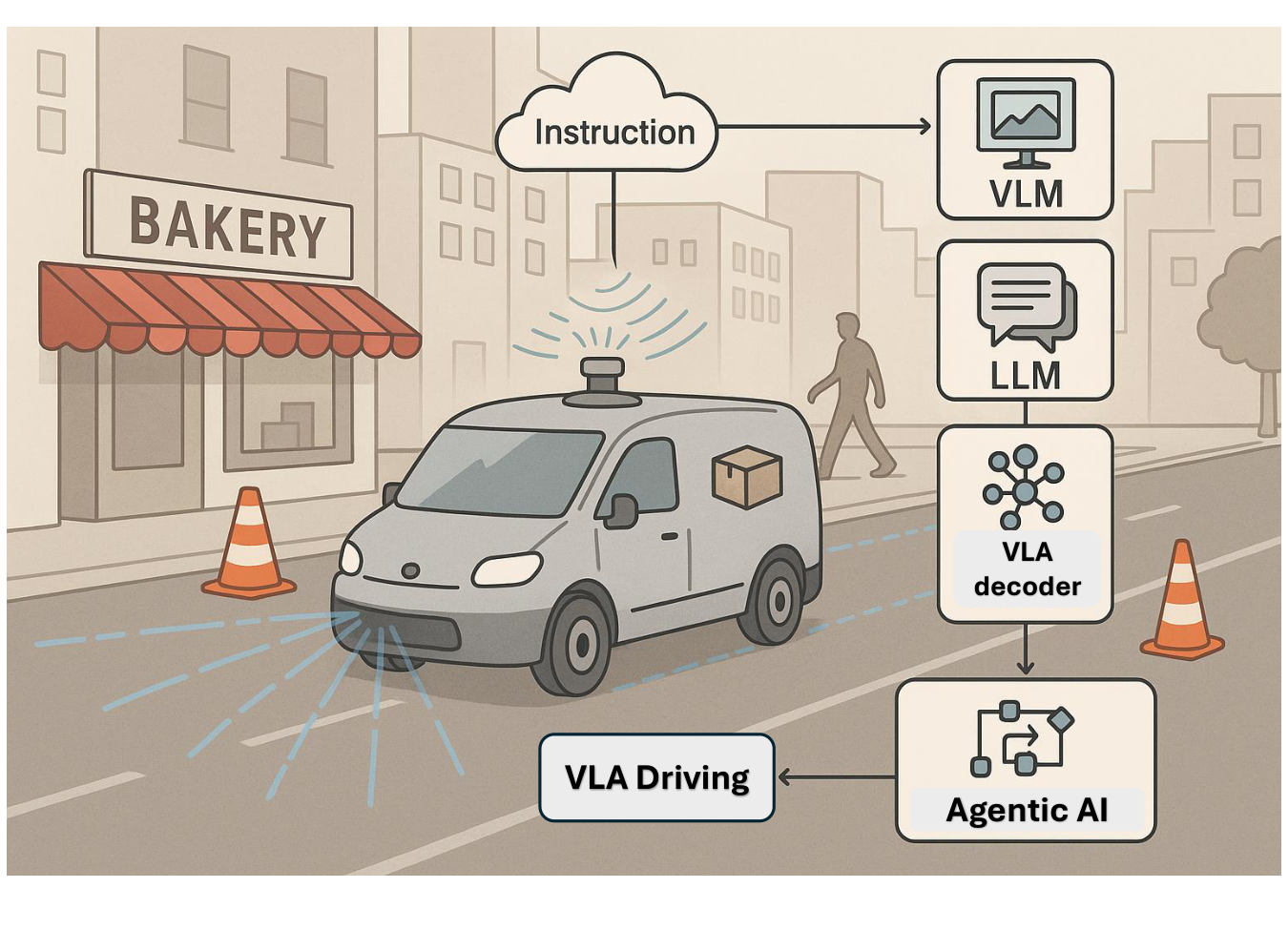

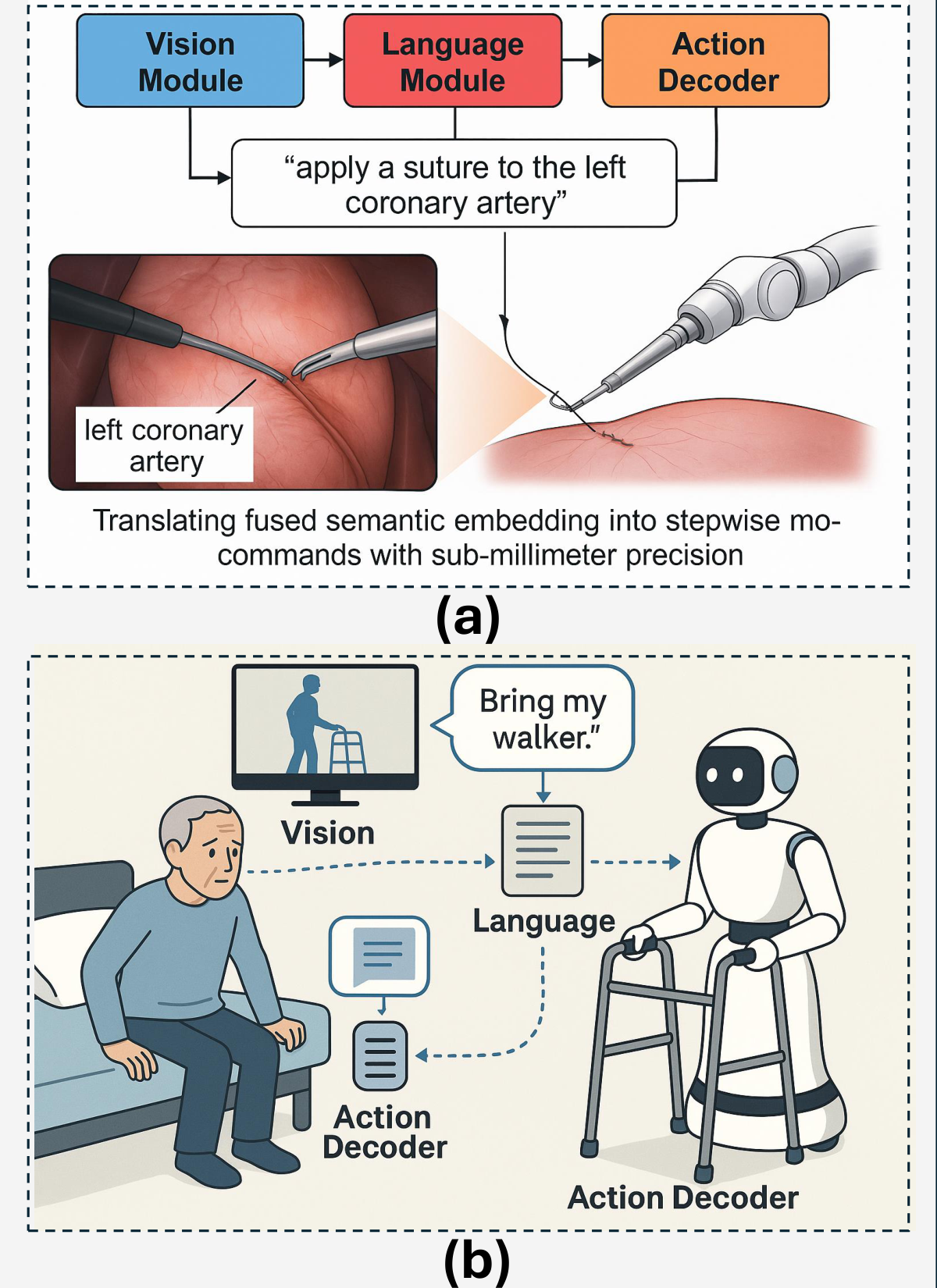

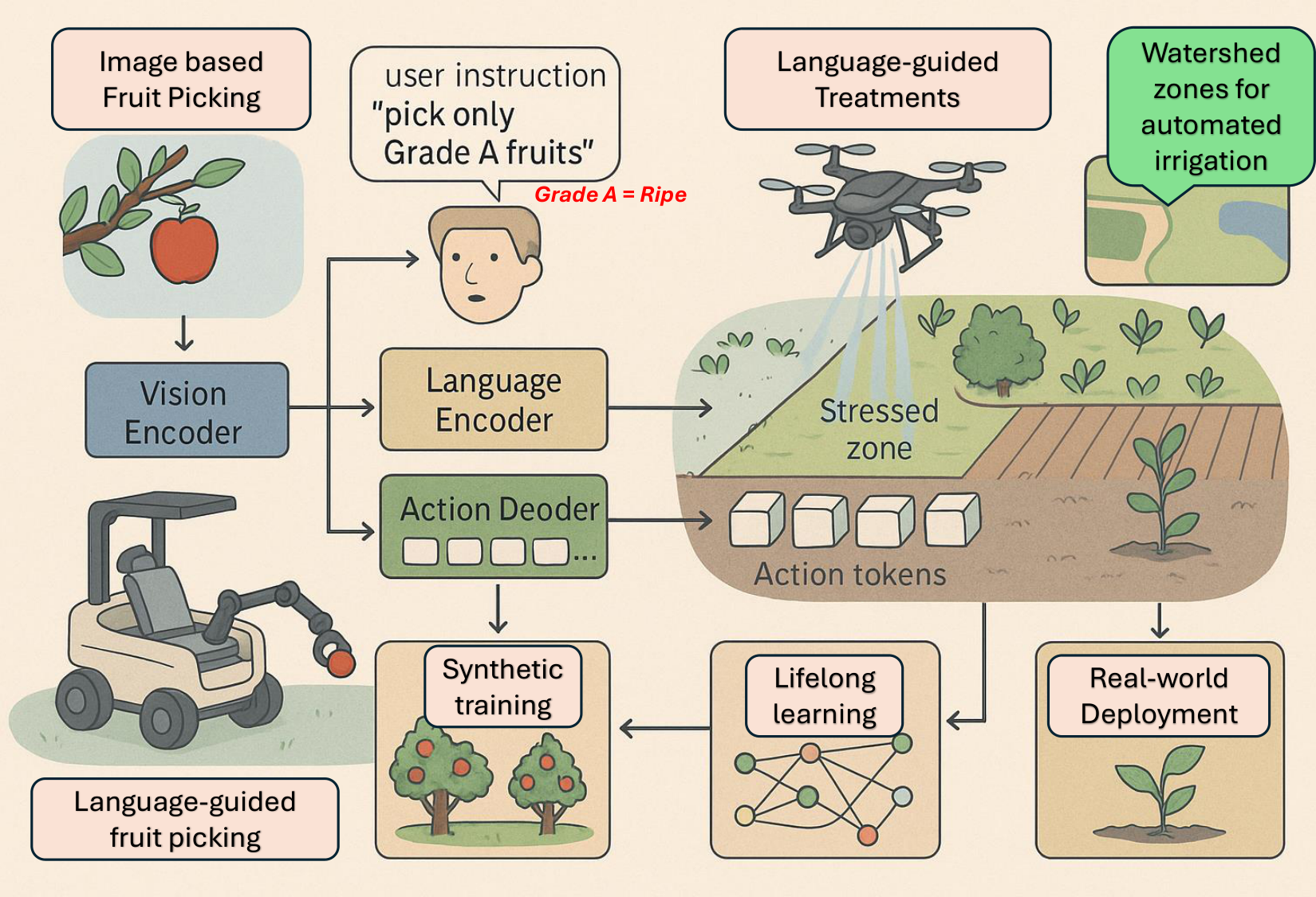

Application demonstrations: In humanoid robotics, systems like Helix perform full-body manipulation at 200 Hz, generalizing across unseen objects without task-specific retraining. Autonomous vehicle models (CoVLA, OpenDriveVLA, ORION) process multi-view sensor streams and natural language instructions to generate interpretable driving trajectories, achieving state-of-the-art planning accuracy and visual question-answering performance. Industrial VLAs such as CogACT outperform earlier models by 59% on real-world manipulation tasks through diffusion-based action modeling and rapid cross-embodiment adaptation. In healthcare, RoboNurse-VLA demonstrates real-time surgical instrument handover with robustness to tool novelty and dynamic operating room conditions. Agricultural applications show VLA-equipped robots achieving selective fruit picking with minimal crop damage and adaptive irrigation reducing water usage by 30%.

Persistent limitations: Real-time inference remains constrained—autoregressive decoding typically achieves only 3–5 Hz, far below the 100+ Hz required for precise robotic control. Parallel decoding methods like those in Groot N1 offer 2.5× speedups but introduce trajectory smoothness trade-offs unacceptable in sensitive applications. Multimodal action representation suffers from discrete tokenization imprecision (errors in 256-bin quantization schemes) or continuous MLP mode collapse, while diffusion-based alternatives incur 3× computational overhead. Safety mechanisms exhibit 200–500ms latency and collision prediction accuracy of only 82% in cluttered environments. Dataset bias affects approximately 17% of object associations, causing 23% reference-missing rates in novel settings. Generalization drops 40% on entirely novel tasks due to overfitting narrow training distributions. System integration faces temporal mismatches between 800ms LLM planning and 10ms control loops, and energy demands of 7-billion-parameter models (28+ GB VRAM) exceed edge hardware capacities.

Implications and Significance

These findings reveal that VLA models have transitioned from research prototypes to deployable systems in controlled environments, but significant gaps remain before widespread real-world adoption. The dual-system architecture breakthrough demonstrates that separating strategic reasoning from reactive control can substantially improve performance on complex tasks, suggesting this design pattern should guide future development. Training efficiency advances democratize VLA technology—smaller research groups and companies can now fine-tune billion-parameter models on consumer-grade GPUs, accelerating innovation outside well-resourced labs.

Application demonstrations prove VLAs can handle safety-critical domains like surgery and autonomous driving when properly validated, but the 82% collision prediction accuracy and 200–500ms emergency stop latency indicate current systems cannot yet meet the reliability standards required for unsupervised operation in high-stakes environments. The 40% performance degradation on novel tasks highlights that despite multimodal learning, today's VLAs still require substantial task-specific data, limiting their value proposition as "generalist" agents. The pervasive dataset bias affecting 17% of associations raises concerns about equitable deployment—systems trained predominantly on Western, urban datasets may fail or exhibit biased behavior when deployed in diverse global contexts.

From a cost perspective, training efficiency breakthroughs reduce development expenses from millions of dollars in cloud compute to tens of thousands for academic-scale projects, enabling broader participation. However, inference costs remain high—real-time VLA operation on embedded hardware requires specialized accelerators (Jetson, tensor cores) or model compression trade-offs that sacrifice accuracy. Organizations must weigh deployment context carefully: applications tolerating 3–5 Hz inference (warehouse sorting, agricultural monitoring) can use current VLAs profitably, while applications requiring 100+ Hz (surgical robotics, high-speed manipulation) need further algorithmic and hardware advances.

Recommendations and Next Steps

For immediate deployment (0–12 months): Organizations should deploy VLAs in applications tolerating moderate latency (3–10 Hz) and accepting 15–20% failure rates with human oversight: warehouse sorting, agricultural monitoring, simple pick-and-place tasks, and guided navigation in structured environments. Adopt dual-system architectures separating planning from control, use parameter-efficient fine-tuning (LoRA) to adapt pretrained models like OpenVLA to specific tasks with minimal data (reducing development time by 60–70%), and implement quantization for edge deployment where real-time inference is needed. Establish human-in-the-loop mechanisms for error recovery and continuous learning, and curate domain-specific validation datasets to audit for bias before deployment.

For medium-term development (1–3 years): Research priorities should focus on accelerating inference through model-architecture co-design with hardware manufacturers to achieve 100+ Hz on edge devices, developing hybrid action representations balancing discrete precision with continuous flexibility, and integrating formal verification methods to guarantee safety properties for critical applications. Expand cross-embodiment datasets and training methods to enable zero-shot transfer across robot morphologies, reducing per-platform development costs. Create standardized benchmarks for safety, robustness, and bias evaluation specific to VLA systems, as current metrics inadequately capture real-world deployment requirements. Pilot VLA systems in semi-autonomous modes in healthcare (surgical assistance with surgeon oversight) and transportation (driver-assist rather than full autonomy) to build reliability data and regulatory acceptance.

For long-term vision (3+ years): The field should pursue convergence of VLAs with agentic AI systems capable of self-supervised continual learning—robots generating their own exploration objectives and improving skills autonomously over deployment lifetimes. Develop hierarchical neuro-symbolic planning integrating interpretable task decomposition with learned motor primitives, enabling transparent decision-making required for regulated domains. Advance world models providing real-time predictive simulation to enable model-based corrective actions during unexpected events. Establish comprehensive regulatory frameworks addressing VLA safety certification, liability allocation, and ethical deployment standards before large-scale autonomous operation. Foster cross-disciplinary collaboration between robotics, AI ethics, human factors, and domain experts (surgeons, farmers, logistics operators) to ensure VLA systems augment rather than displace human expertise.

Decision points requiring attention: Organizations must decide whether to build proprietary VLA systems or adopt open-source foundations like OpenVLA—the latter reduces initial investment but may limit competitive differentiation. Policymakers should determine appropriate oversight mechanisms balancing innovation enablement with public safety, particularly for VLAs in healthcare, transportation, and public spaces. Researchers must choose between pursuing incremental improvements to existing transformer-based architectures versus exploring alternative paradigms (state-space models, neuromorphic computing) that might offer step-change efficiency gains.

Limitations and Confidence

This review's primary limitation is its literature-based methodology—findings reflect published research, which may lag proprietary industrial developments by 6–18 months, particularly from well-resourced companies (Google DeepMind, NVIDIA, Tesla). Performance metrics across studies vary in evaluation protocols, making direct comparisons imprecise; stated success rates should be interpreted as indicative trends rather than precise benchmarks. The rapid pace of VLA development (47 major models in three years) means conclusions may be quickly superseded by new architectures or training methods.

Confidence in architectural findings is high—the convergence toward dual-system designs and token-based representations across independent research groups indicates robust design principles. Confidence in application readiness is moderate for structured industrial settings but low for unstructured real-world deployment, as most reported results come from controlled laboratory or simulation environments rather than extended field trials. The gap between simulation and real-world performance typically ranges from 15–35% across robotics applications.

Confidence in the identified challenges is high—real-time inference constraints, safety limitations, and dataset bias are consistently reported across diverse research groups and domains. However, confidence in proposed solutions is moderate to low, as most represent emerging research directions rather than validated approaches. Parameter-efficient training methods (LoRA, quantization) are well-established with reproducible results, but advanced concepts like neuro-symbolic planning and cross-embodiment generalization remain largely aspirational.

Readers should exercise caution when extrapolating laboratory success rates to production environments—expect 20–40% degradation without extensive domain-specific validation. Safety-critical applications (surgery, autonomous driving) should not rely on current VLA systems without redundant safeguards and human oversight, as failure modes remain incompletely characterized. Organizations evaluating VLA adoption should conduct pilot deployments in low-risk scenarios before scaling, allocating 30–50% of project budgets to dataset curation, bias auditing, and failure-mode analysis rather than model development alone.

b^{b}b The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Hong Kong

c^{c}c University of the Peloponnese, Department of Informatics and Telecommunications, Greece

Email address: [email protected] (Manoj Karkee)

Abstract

1. Introduction

In this section, the fundamental limitation of pre-VLA artificial intelligence is exposed: vision, language, and action systems operated in isolation, unable to collaborate or generalize beyond narrow tasks, leaving robots incapable of flexible real-world behavior. Traditional computer vision models could recognize objects but not understand language or execute actions; language models processed text without perceiving the physical world; and action-based robotics required hand-crafted policies that failed to adapt. Even vision-language models, despite achieving impressive multimodal understanding, lacked the critical ability to generate executable actions, resulting in fragmented pipelines that could not unify perception, reasoning, and control. Vision-Language-Action models emerged around 2021-2022, pioneered by systems like RT-2, to bridge this gap by integrating all three modalities into a single end-to-end framework using action tokens and internet-scale multimodal datasets. This breakthrough enables robots to perceive environments, interpret natural language instructions, and execute adaptive actions, representing a transformative step toward truly generalizable embodied intelligence.

2. Concepts of Vision-Language-Action Models

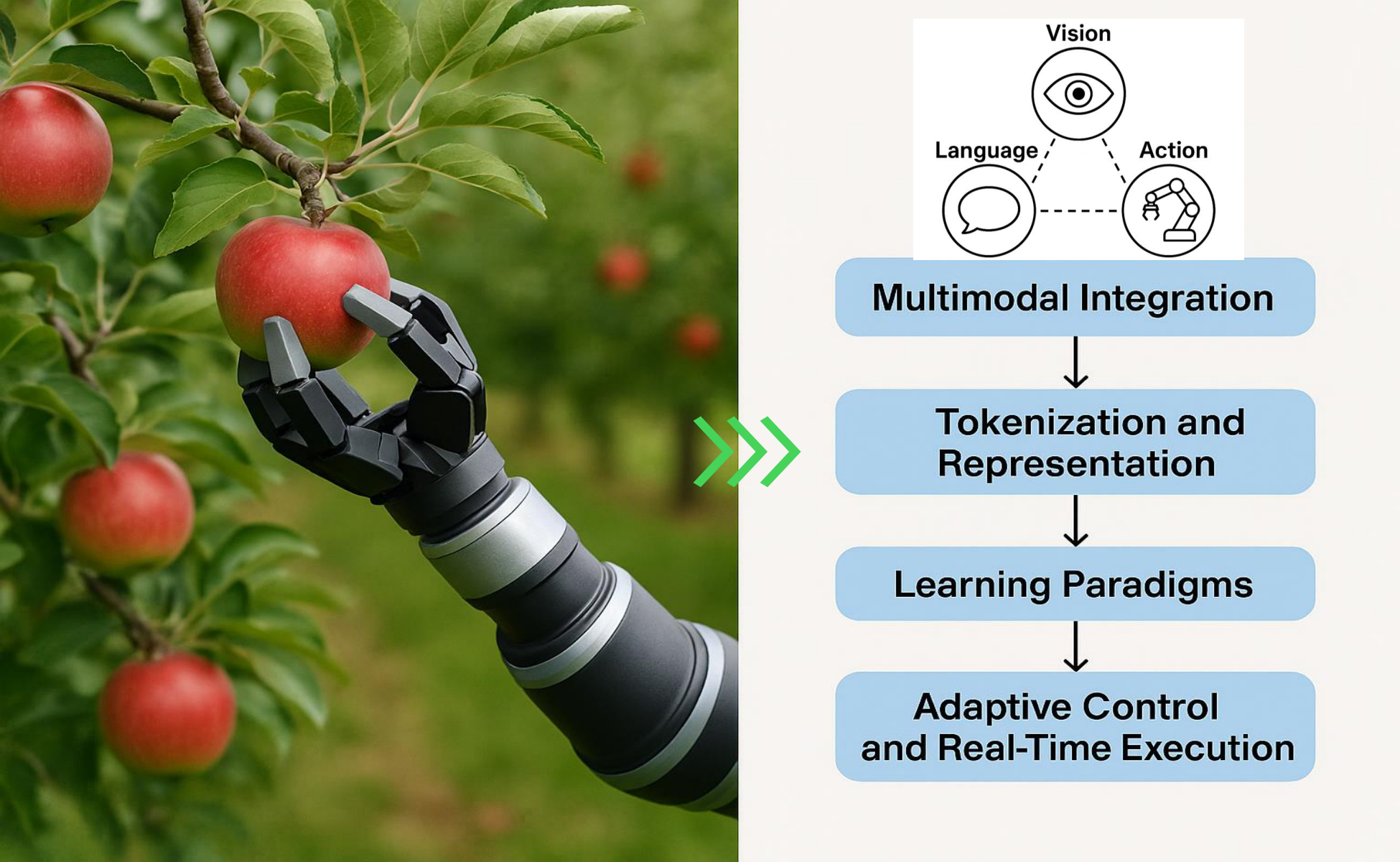

In this section, VLA models emerge as unified AI frameworks that overcome the fragmentation of isolated vision, language, and action systems by jointly processing visual inputs, natural language instructions, and motor control within a single end-to-end architecture. Unlike traditional pipelines requiring manual interfaces and domain-specific engineering, VLAs leverage multimodal integration through pretrained encoders and transformer-based fusion to enable context-aware reasoning and generalization across novel tasks. Their token-based representation framework unifies perceptual, linguistic, and action spaces using prefix tokens for contextual grounding, state tokens for proprioceptive awareness, and autoregressively generated action tokens for precise control execution. Training combines internet-scale vision-language data with robotic demonstrations through imitation learning, reinforcement learning, and retrieval-augmented methods, while adaptive control mechanisms enable real-time behavioral adjustments via continuous sensor feedback. This paradigm shift transforms robots from brittle, task-specific machines into flexible, semantically grounded agents capable of interpreting complex instructions and executing dynamic manipulations in unstructured environments.

2.1. Evolution and Timeline

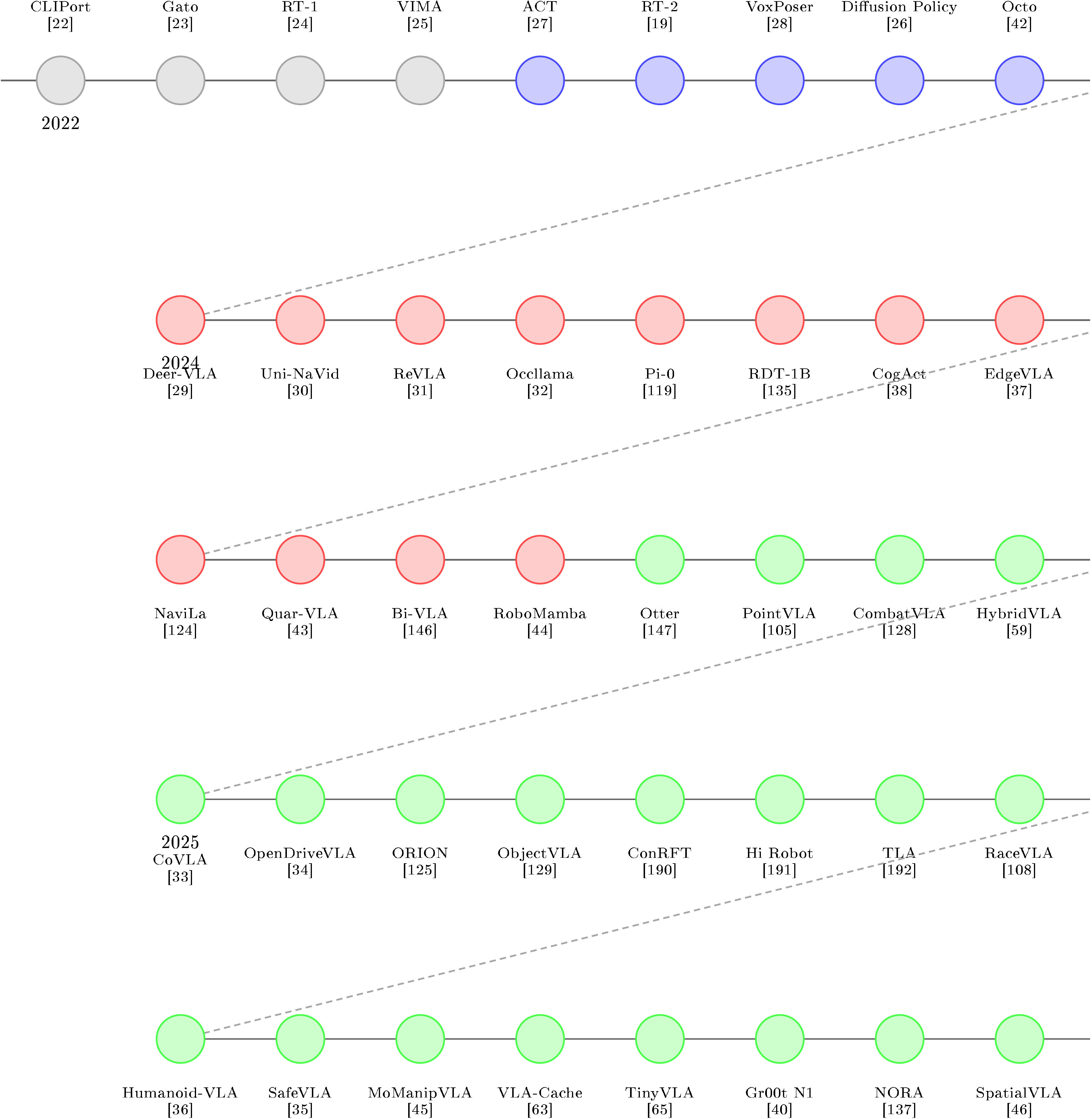

- Foundational Integration (2022–2023). Early VLAs established basic visuomotor coordination through multimodal fusion architectures. [22] first combined CLIP embeddings with motion primitives, while [23] demonstrated generalist capabilities across 604 tasks. [24] achieved 97% success rates in manipulation through scaled imitation learning, and [25] introduced temporal reasoning via transformer-based planners. By 2023, [19] enabled visual chain-of-thought reasoning, and [26] advanced stochastic action prediction through diffusion processes. These foundations addressed low-level control but lacked compositional reasoning [27], prompting innovations in affordance grounding [28].

- Specialization and Embodied Reasoning (2024). Second-generation VLAs incorporated domain-specific inductive biases. [29] enhanced few-shot adaptation through retrieval-augmented training, while [30] optimized navigation via 3D scene-graph integration. [31] introduced reversible architectures for memory efficiency, and [32] addressed partial observability with physics-informed attention. Simultaneously, [33] improved compositional understanding through object-centric disentanglement, and [34] extended applications to autonomous driving via multi-modal sensor fusion. These advances required new benchmarking methodologies [21].

- Generalization and Safety-Critical Deployment (2025). Current systems prioritize robustness and human alignment. [35] integrated formal verification for risk-aware decisions, while [36] demonstrated whole-body control through hierarchical VLAs. [37] optimized compute efficiency for embedded deployment, and [38] combined neural-symbolic reasoning for causal inference. Emerging paradigms like [39]'s affordance chaining and [40]'s sim-to-real transfer learning address cross-embodiment challenges, while [41] bridges VLAs with human-in-the-loop interfaces through natural language grounding.

2.2. Multimodal Integration: From Isolated Pipelines to Unified Agents

2.3. Tokenization and Representation: How VLAs Encode the World

-

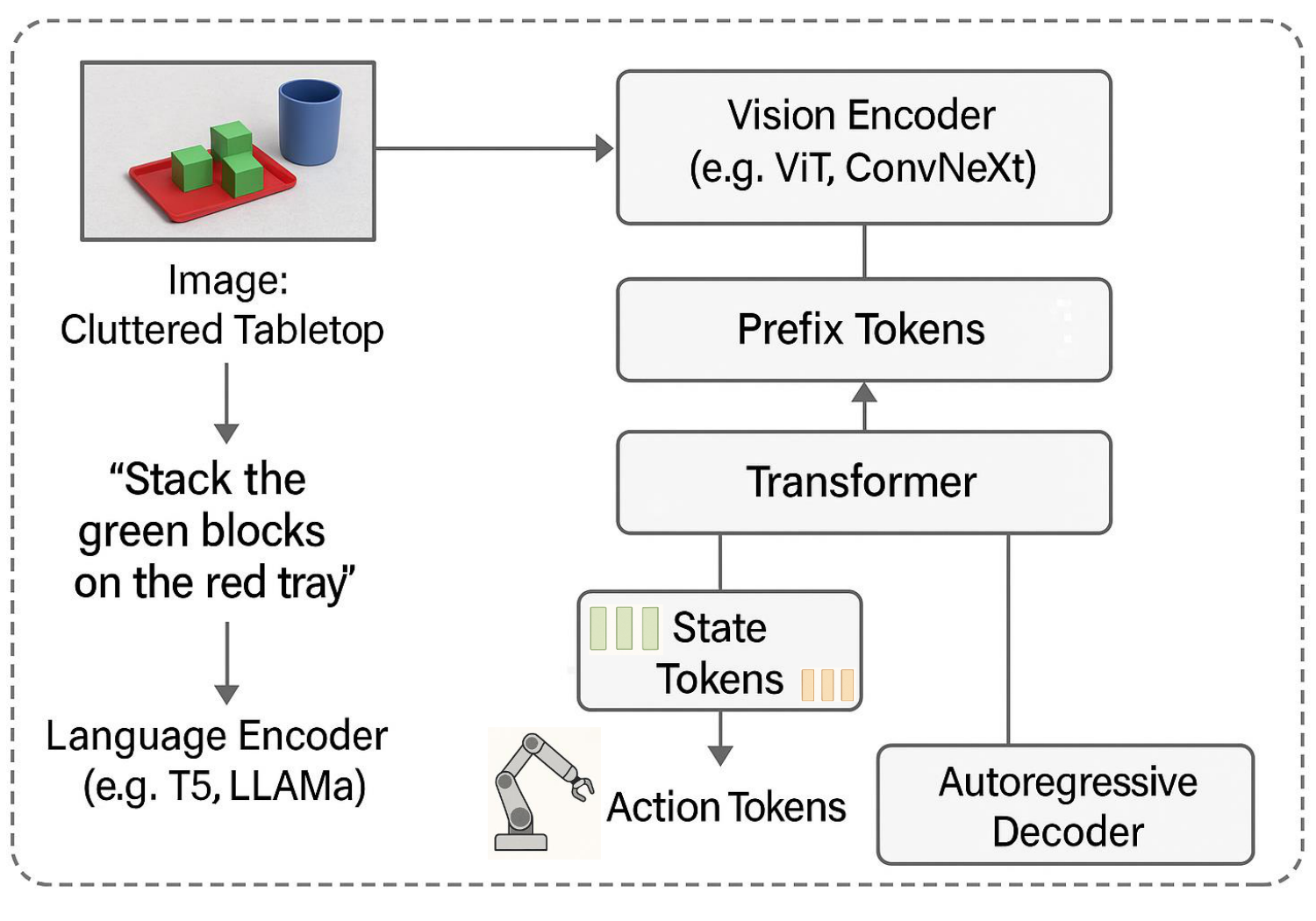

**Prefix Tokens: Encoding Context and Instruction:**Prefix tokens serve as the contextual backbone of VLA models [63, 20]. These tokens encode the environmental scene (via images or video) and the accompanying natural language instruction into compact embeddings that prime the model's internal representations [64]. {#fig_prefix}For instance, as depicted in Figure 7 in a task such as “stack the green blocks on the red tray, ” the image of a cluttered tabletop is processed through a vision encoder like ViT or ConvNeXt, while the instruction is embedded by a large language model (e.g., T5 or LLaMA). These are then transformed into a sequence of prefix tokens that establish the model’s initial understanding of the goal and environmental layout. This shared representation enables cross-modal grounding, allowing the system to resolve spatial references (e.g., “on the left, ” “next to the blue cup”) and object semantics (“green blocks”) across both modalities.

-

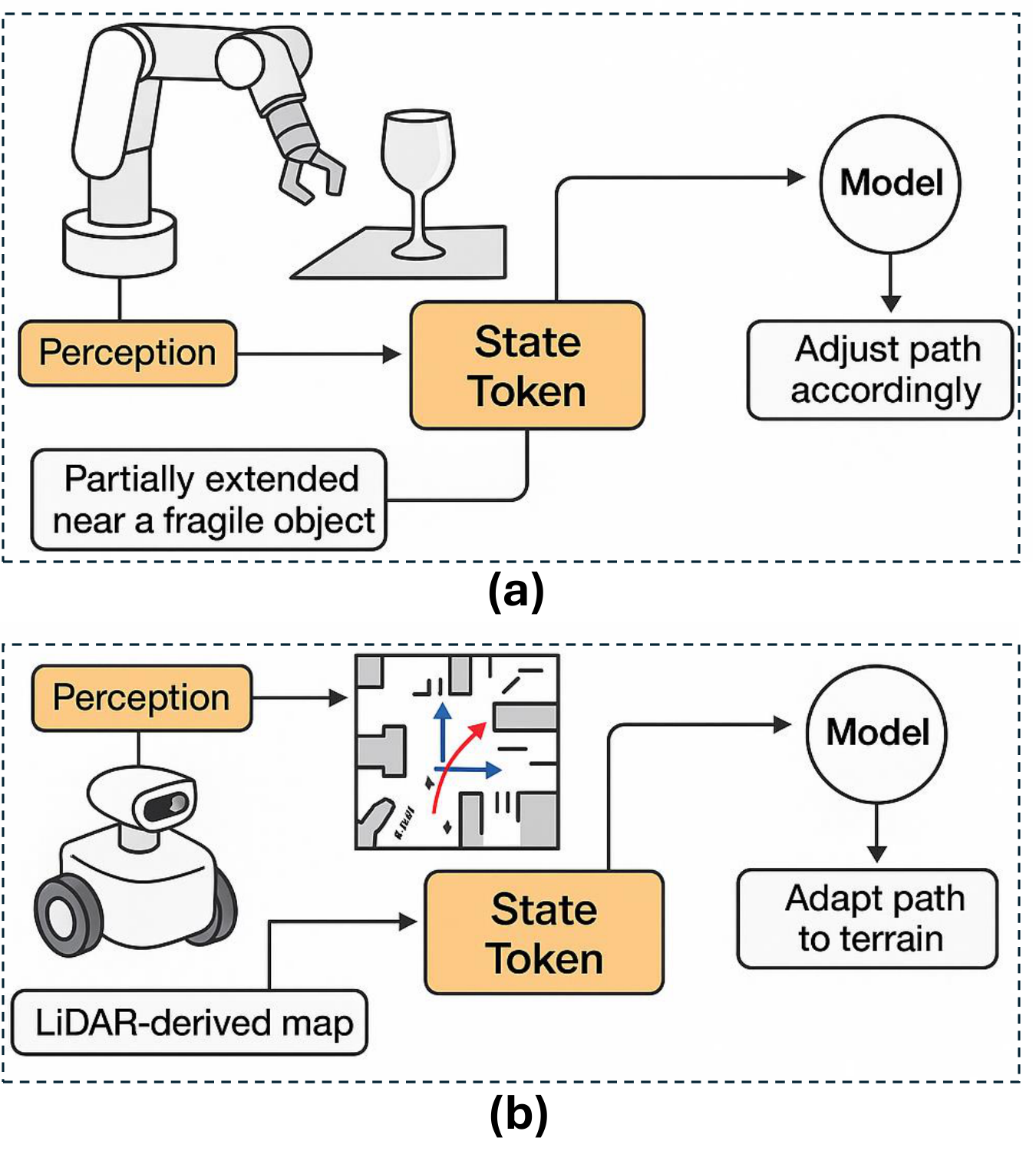

State Tokens: Embedding the Robot's Configuration: In addition to perceiving external stimuli, VLAs must be aware of their internal physical state [65, 44]. This is achieved through the use of state tokens, which encode real-time information about the agent's configuration—joint positions, force-torque readings, gripper status, end-effector pose, and even the locations of nearby objects [66]. These tokens are crucial for ensuring situational awareness and safety, especially during manipulation or locomotion [67, 68].Figure 8 illustrates how VLA models utilize state tokens to enable dynamic, context-aware decision-making in both manipulation and navigation settings. In Figure 8 a, a robot arm is shown partially extended near a fragile object. In such scenarios, state tokens play a critical role by encoding real-time proprioceptive information, such as joint angles, gripper pose, and end-effector proximity. These tokens are continuously fused with visual and language-based prefix tokens, allowing the transformer to reason about physical constraints. The model can thus infer that a collision is imminent and adjust the motor commands accordingly—e.g., rerouting the arm trajectory or modulating force output. In mobile robotic platforms, as depicted in Figure 8 b, state tokens encapsulate spatial features such as odometry, LiDAR scans, and inertial sensor data. These are essential for terrain-aware locomotion and obstacle avoidance. The transformer model integrates this state representation with environmental and instructional context to generate navigation actions that dynamically adapt to changing surroundings. Whether grasping objects in cluttered environments or autonomously navigating uneven terrain, state tokens provide a structured mechanism for situational awareness, enabling the autoregressive decoder to produce precise, context-informed action sequences that reflect both internal robot configuration and external sensory data.

-

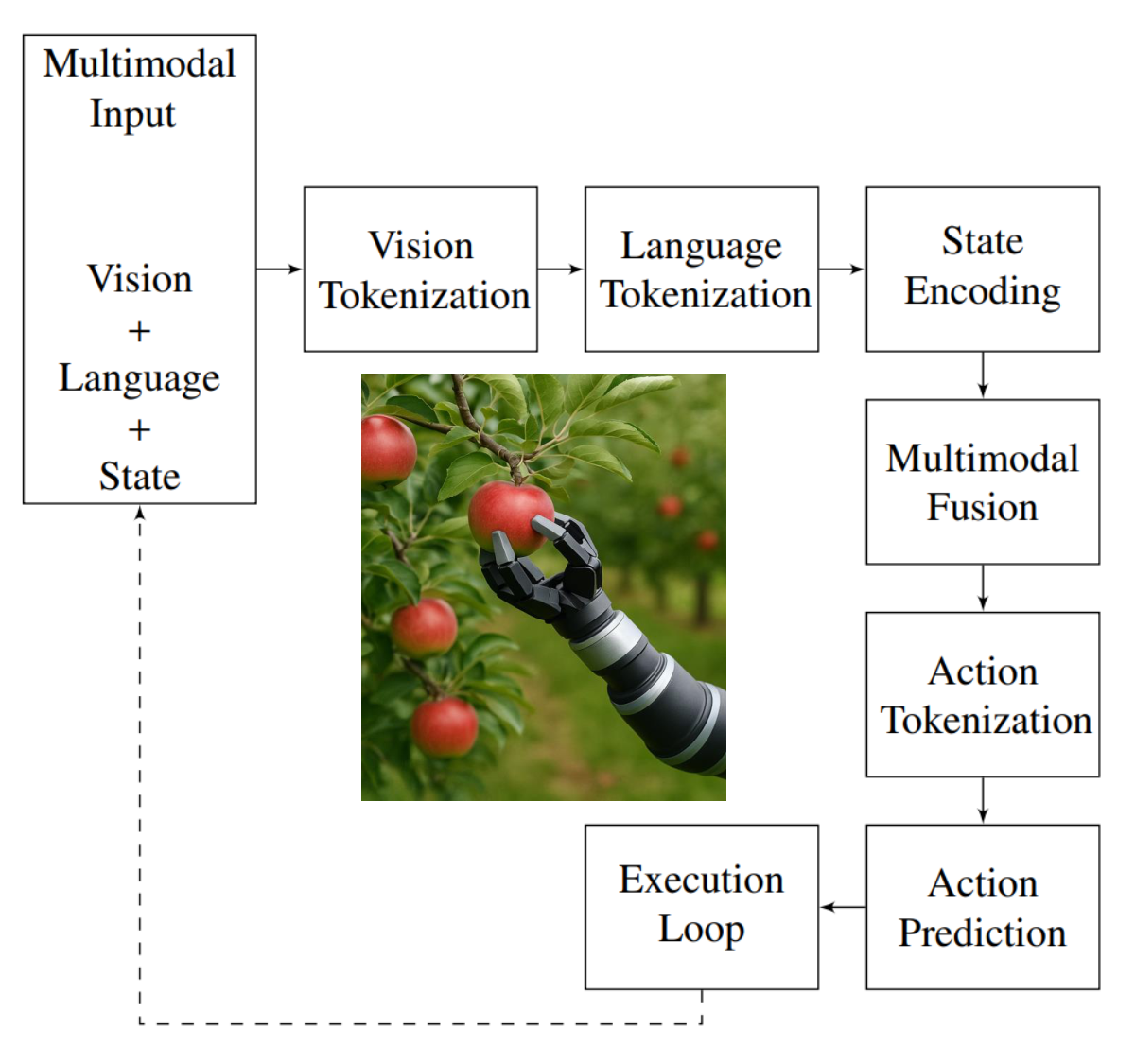

Action Tokens: Autoregressive Control Generation: The final layer of the VLA token pipeline involves action tokens [69, 70], which are autoregressively generated by the model to represent the next step in motor control [65]. Each token corresponds to a low-level control signal, such as joint angle updates, torque values, wheel velocities, or high-level movement primitives [71]. During inference, the model decodes these tokens one step at a time, conditioned on prefix and state tokens, effectively turning VLA models into language-driven policy generators [72, 73]. This formulation allows seamless integration with real-world actuation systems, supports variable-length action sequences [74, 75], and enables model fine-tuning via reinforcement or imitation learning frameworks [76]. Notably, models like RT-2 [19] and PaLM-E [77] exemplify this design, where perception, instruction, and embodiment are merged into a unified token stream.For instance, in the apple-picking task as depicted in Figure 9, the model may receive prefix tokens that include the image of the orchard and the text instruction. The state tokens describe the robot's current arm posture and whether the gripper is open or closed. Action tokens are then predicted step by step to guide the robotic arm toward the apple, adjust the gripper orientation, and execute a grasp with appropriate force. The beauty of this approach is that it allows transformers, which are traditionally used for text generation, to now generate sequences of physical actions in a manner similar to generating a sentence—only here, the sentence is the motion.

Transformer object is initialized with 12 layers, a model dimension of 512, and 8 attention heads. The fused tokens are passed to the decoder, which autoregressively predicts the next most likely action token conditioned on previous tokens and context. The final motor command sequence is obtained by detokenizing the output. This implementation mirrors how text generation works in large language models, but here the “sentence” is a motion trajectory—a novel repurposing of natural language generation techniques for physical action synthesis.# Python-like pseudocode

def predict_actions(fused_tokens):

transformer = Transformer(

num_layers=12,

d_model=512,

nhead=8

)

action_tokens = transformer.decode(

fused_tokens,

memory=fused_tokens2.4. Learning Paradigms: Data Sources and Training Strategies

2.5. Adaptive Control and Real-Time Execution

3. Progress in Vision-Language-Action Models

In this section, Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models emerged from the convergence of large language models like ChatGPT and multimodal vision-language systems such as CLIP, which established robust visual-text alignment through contrastive learning on web-scale datasets. The creation of large robotic datasets, notably RT-1's 130,000 demonstrations, enabled action-grounding essential for training models that unify perception, language, and motor control. Architectural innovations followed rapidly: RT-2 pioneered autoregressive action token generation using transformer decoders, while dual-system architectures like NVIDIA's Groot N1 separated fast reactive control from strategic planning. Models evolved from early fusion designs that preserve CLIP alignment to self-correcting frameworks capable of failure recovery through chain-of-thought reasoning. Training paradigms shifted toward co-fine-tuning on internet-scale vision-language corpora and robotic trajectory data, with techniques like LoRA adapters reducing computational costs by 70%. These advances democratized VLA technology, enabling generalization across tasks, embodiments, and domains while balancing real-time execution with high-level cognitive planning.

In this section, the references catalog a comprehensive body of work spanning foundational vision-language research, neural architectures, and robotics applications that underpin the development of Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models. Early studies established multimodal integration through recurrent convolutional networks for visual recognition and description, while generative pre-training and transformer architectures enabled scalable language understanding. Subsequent advances introduced robot-specific policies like RT-1, RT-2, and VIMA, which unified visual perception, natural language instructions, and action execution through end-to-end learning. The literature also addresses critical challenges including real-time inference optimization via quantization and low-rank adaptation, generalization through cross-embodiment transfer and meta-learning, and ethical concerns such as bias in vision-language datasets and safe human-robot interaction. Collectively, these works trace the evolution from isolated perception-action modules to integrated, instruction-following agents capable of operating in complex, unstructured environments, while highlighting ongoing efforts to enhance efficiency, robustness, and societal alignment in embodied AI systems.

3.1. Architectural Innovations in VLA Models

• Language Encoder: CLIP-GPT

• Action Decoder: LingUNet | Self-collected [SC] | Combines semantic CLIP features with spatial Transporter network for precise SE(2) manipulation. |

• Language Encoder: Universal Sentence Encoder

• Action Decoder: Transformer | RT-1-Kitchen [SC] | Pioneering Transformer architecture with discretized actions for multi-task kitchen manipulation. |

• Language Encoder: PaLI-X/PaLM-E

• Action Decoder: Symbol-tuning | VQA + RT-1-Kitchen | First large VLA co-finetuned on internet VQA data and robot data for emergent capabilities. |

• Language Encoder: SentencePiece

• Action Decoder: Transformer | Self-collected [SC] | Generalist agent handling Atari, captioning, and robotics through unified tokenization. |

• Language Encoder: T5

• Action Decoder: Transformer | VIMA-Data [SC] | Multi-modal prompt handling with 6 types of vision-language grounding tasks. |

• Language Encoder: —

• Action Decoder: CVAE-Transformer | ALOHA [SC] | Temporal ensembling for smooth bimanual manipulation with 0.1mm precision. |

• Language Encoder: T5-base

• Action Decoder: Diffusion Transformer | Open X-Embodiment | First policy trained on 4M+ robot trajectories from 22 robot types. |

• Language Encoder: GPT-4

• Action Decoder: MPC | Zero-shot | LLM+VLM composition for constraint-aware motion planning without training. |

• Language Encoder: —

• Action Decoder: U-Net/Transformer | Self-collected [SC] | Pioneering diffusion-based visuomotor policy handling multimodal action distributions. |

• Language Encoder: Prismatic-7B

• Action Decoder: Symbol-tuning | OXE + DROID | Open-source alternative to RT-2 with efficient LoRA fine-tuning. |

- Vision Encoder: PaliGemma VLM backbone

- Language Encoder: PaliGemma (multimodal)

- Action Decoder: 300M-parameter diffusion model

• Language Encoder: PaliGemma (multimodal)

• Action Decoder: Autoregressive Transformer with FAST (Frequency-space Action Sequence Tokenization) | Pi- Cross-Embodiment Robot dataset | Variant of Pi-0 optimized for high-frequency, real-time control using compressed action tokens; achieves up to 15x faster inference for discrete robot actions and strong generalization. |

- Vision Encoder: SigLIP + DINOv2 (multi-view)

- Language Encoder: Llama-2 7B

- Action Decoder: Parallel decoding with action chunking and L1 regression

• Language Encoder: Transformer-based language module

• Action Decoder: Diffusion Transformer with unified action space | 1M+ multi-robot episodes (46 datasets), fine-tuned on 6K+ bimanual ALOHA episodes | 1.2B-parameter diffusion foundation model for bimanual manipulation; excels at language-conditioned, dexterous control and zero-shot generalization, with strong but task-specific performance in multi-object settings. |

• Language Encoder: Integrated with VLM for broad generalization and semantic comprehension

• Action Decoder: Transformer-based visuomotor policy (System 1) for continuous, full upper-body control at 200 Hz | End-to-end on Figure robot data (pixels and language to actions) | First VLA model for real-time, high-DoF humanoid control; enables zero-shot generalization, fine-grained dexterity, and collaborative multi-robot manipulation in open-world tasks. |

• Language Encoder: Llama-2 (via Prismatic-7B VLM)

• Action Decoder: Diffusion Transformer (DiT-Base, 300M parameters) | Open X-Embodiment (OXE) subset, real-world Realman & Franka tasks | Componentized VLA with specialized diffusion action transformer; outperforms OpenVLA by 59.1% in real-world success, excels at adaptation and generalization to new robots and unseen objects. |

• Language Encoder: Transformer-based language module for sequential reasoning prompts

• Action Decoder: Autoregressive and diffusion policy with affordance-conditioned outputs | LIBERO benchmark, real and simulated manipulation tasks | Incorporates reasoning via sequential affordances (object, grasp, spatial, movement); achieves superior LIBERO performance over OpenVLA, excelling in spatial reasoning and obstacle avoidance for precise task completion. |

• Language Encoder: Qwen2 (0.5B parameters)

• Action Decoder: Joint control prediction (non-autoregressive) | Bridge dataset, OXE, 1.2M text-image pairs | Lightweight VLA model optimized for edge devices (e.g., Jetson Nano) with 30–50 Hz inference; achieves performance comparable to OpenVLA while enabling efficient, real-time deployment on low-power hardware. |

• Language Encoder: Interleaved vision-language-action streaming

• Action Decoder: Transformer for GUI action sequence prediction | 256K high-quality GUI instruction-following dataset | Lightweight 2B-parameter VLA specialized for digital task automation; excels at GUI/web navigation and screenshot grounding with efficient token selection and unified vision-language-action reasoning. |

• Language Encoder: Integrated with VLM for high-level planning and reasoning

• Action Decoder: Diffusion Transformer (DiT) for precise, high-frequency action generation | Multimodal data: human demonstrations, robot trajectories, synthetic simulation, and internet video | Hybrid dual-system architecture for generalist humanoid robots, combining high-level planning with diffusion-based execution; enables dexterous, multi-step control and strong generalization across tasks and embodiments. |

• Language Encoder: Transformer-based language module

• Action Decoder: Autoregressive action prediction head | LIBERO benchmark | VLA model focused on visual perception and action prediction; achieves competitive results with strong visual grounding for manipulation, but is outperformed by OpenVLA-OFT [1][6][8][10]. |

• Language Encoder: Autoregressive reasoning module with next-token prediction

• Action Decoder: Diffusion policy head for robust action sequence generation | LIBERO benchmark, factory sorting, zero-shot bin-picking tasks | Leverages diffusion-based action modeling for precise control; demonstrates robustness and interpretability, but is less generalizable than CoA in spatial configurations. |

• Language Encoder: LLaMA-2 (task command + nav goal)

• Action Decoder: Two-level controller: topological graph planner + RL-based locomotion | Real-world legged robot nav demos | Modular hierarchy enables robust terrain generalization and 88% real-world nav success using natural language |

• Language Encoder: LLaMA 2 + voice-to-text encoder

• Action Decoder: Joint pose regression with gripper classifier | Surgical handover videos and voice prompts | Enables accurate, real-time surgical tool handover; strong robustness to tool novelty and dynamic OR scenes |

• Language Encoder: T5-based instruction encoder

• Action Decoder: Graph planner with visual goal localization | MINT dataset: vision-language instruction tours | Robust navigation from multimodal input; generalizes across large unseen spaces via topological mapping |

• Language Encoder: Compact language encoder (128-d)

• Action Decoder: Diffusion policy decoder (50M params) | Mini-ALOHA + SC tasks | Outperforms OpenVLA in speed and precision; does not require pretraining; inference 5x faster with minimal compute |

• Language Encoder: BERT + custom grounding adapter

• Action Decoder: Transformer for full-body command decoding | QUART dataset (locomotion + manipulation) | Quadruped-specific control with strong sim-to-real transfer and fine-grained instruction alignment |

• Language Encoder: Prismatic LLM with Mixture-of-Experts

• Action Decoder: Unified vision-language-action planner | Unified chat-action dataset (web, robot) | Excels at joint VQA and planning; mitigates forgetting; efficient across manipulation and conversational tasks |

• Language Encoder: LLaMA-2

• Action Decoder: Transformer with spatial token fusion | Few-shot spatial tasks (real + sim) | Excels at long-horizon and spatial reasoning tasks; avoids retraining by preserving pretrained 2D knowledge |

• Language Encoder: Prismatic-7B

• Action Decoder: Transformer with dynamic token reuse | ALOHA + real-world sim fusion | 40–50% faster inference with near-zero loss; dynamically reuses static features for real-time robotics |

• Language Encoder: LLaMA-2

• Action Decoder: Hybrid diffusion + autoregressive ensemble | RT-X + synthetic task fusion | Achieves robust control in complex multi-arm settings via dynamic ensemble; strong sim2real generalization |

• Language Encoder: CogKD-enhanced transformer

• Action Decoder: Sparse transformer with dynamic routing | RLBench + real-world manipulation tasks | Brain-inspired efficiency with 5.6x speedup; selective layer activation with high task success (+8%) |

• Language Encoder: GPT for instruction parsing

• Action Decoder: Transformer-based path planner | Satellite + UAV imagery instructions | Zero-shot aerial task planning; intuitive language grounding; scalable to large unmapped environments |

• Language Encoder: Transformer with grasp sequence reasoning

• Action Decoder: Diffusion controller for grasp pose generation | Dexterous grasping benchmark (sim + real) | 90%+ zero-shot success on diverse objects; excels at lighting, background variation, and unseen conditions |

• Language Encoder: VLM predicts bounding boxes and grasp poses

• Action Decoder: Flow-matching based action expert via Progressive Action Generation (PAG) | SynGrasp-1B (1B synthetic frames), GRIT (Internet grounding dataset) | First synthetic-data-pretrained grasping VLA; enables sim-to-real generalization, robust grasp policy via PAG; supports zero-shot and few-shot generalization to long-tail object classes and human-centric preferences |

• Language Encoder: Qwen2.5 for instruction parsing and visual-language verification

• Action Decoder: Continuous action predictor adapted from OpenVLA and π0\pi^0π0 with diffusion-policy controller | Open Interleaved X-Embodiment (210k episodes from 11 real-world datasets) | First end-to-end VLA model for interleaved image-text instructions; improves out-of-domain generalization 2–3× and enables zero-shot execution from hand-drawn sketches and novel multimodal prompts |

3.2. Training and Efficiency Advancements in Vision–Language–Action Models

-

Data-Efficient Learning.

- Co-fine-tuning on massive vision–language corpora (e.g. LAION-5B) and robotic trajectory collections (e.g. Open X-Embodiment) aligns semantic understanding with motor skills. OpenVLA (7B parameters) achieves a 16.5% higher success rate than a 55B-parameter RT-2 variant, demonstrating that co-fine-tuning yields strong generalization with fewer parameters [116, 97, 70].

- Synthetic Data Generation via UniSim produces photorealistic scenes—including occlusions and dynamic lighting—to augment rare edge-case scenarios, improving model robustness in cluttered environments by over 20% [117, 42].

- Self-Supervised Pretraining adopts contrastive objectives (à la CLIP) to learn joint visual–text embeddings before action fine-tuning, reducing reliance on task-specific labels. Qwen2-VL leverages self-supervised alignment to accelerate downstream grasp-and-place convergence by 12% [4, 11].

-

Parameter-Efficient Adaptation. Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) inserts lightweight adapter matrices into frozen transformer layers, cutting trainable weights by up to 70% while retaining performance [118]. The Pi-0 Fast variant uses merely 10 M adapter parameters atop a static backbone to deliver continuous 200 Hz control with negligible accuracy loss [86].

-

Inference Acceleration.

- Compressed Action Tokens (FAST) and Parallel Decoding in dual-system frameworks (e.g. Groot N1) yield 2.5× faster policy steps, achieving sub-5 ms latencies at a modest cost to trajectory smoothness [40, 73].

- Hardware-Aware Optimizations—including tensor-core quantization and pipelined attention kernels—shrink runtime memory footprints below 8 GB and enable real-time inference on embedded GPUs [69].

3.3. Parameter-Efficient Methods and Acceleration Techniques in VLA Models

- Low‐Rank Adaptation (LoRA). LoRA injects small trainable rank‐decomposition matrices into frozen transformer layers, enabling fine‐tuning of billion‐parameter VLAs with only a few million additional weights. In OpenVLA, LoRA adapters (20M parameters) tuned a 7 B‐parameter backbone on commodity GPUs in under 24 h, cutting GPU compute by 70% compared to full backpropagation [118, 70]. Crucially, LoRA‐adapted models retain their high‐level language grounding and visual reasoning capabilities while adapting to new robotic manipulation tasks (e.g. novel object shapes), making large VLAs accessible to labs without supercomputing resources.

- Quantization. Reducing weight precision to 8‐bit integers (INT8) shrinks model size by half and doubles on‐chip throughput. OpenVLA experiments show that INT8 quantization on Jetson Orin maintains 97% of full‐precision task success across pick‐and‐place benchmarks, with only a 5% drop in fine‐grained dexterity tasks [116, 70]. Complementary methods such as post‐training quantization with per‐channel calibration further minimize accuracy loss in high‐dynamic‐range sensor inputs [113]. These optimizations allow continuous control loops at 30 Hz on 50 W edge modules.

- Model Pruning. Structured pruning removes entire attention heads or feed‐forward sublayers identified as redundant. While less explored in VLA than in pure vision or language models, early studies on Diffusion Policy demonstrate that pruning up to 20% of ConvNet‐based vision encoders yields negligible performance degradation in grasp stability [26]. Similar schemes applied to transformer‐based VLAs (e.g. RDT‐1B) can reduce memory footprint by 25% with under 2% drop in task success, paving the way for sub‐4 GB deployments [135, 38].

- Compressed Action Tokenization (FAST). FAST reformulates continuous action outputs as frequency‐domain tokens, compressing long control sequences into concise descriptors. The Pi‐0 Fast variant achieved 15× faster inference with a 300 M‐parameter diffusion head by tokenizing 1000 ms action windows into 16 discrete tokens, enabling 200 Hz policy rates on desktop GPUs [86]. This approach trades minimal trajectory granularity for large speedups, suited for high‐frequency control in dynamic tasks like bimanual assembly.

- Parallel Decoding and Action Chunking. Autoregressive VLAs traditionally decode actions token by token, incurring sequential latency. Parallel decoding architectures (e.g. in Groot N1) decode groups of spatial–temporal tokens concurrently, achieving a 2.5× reduction in end‐to‐end latency on 7‐DoF arms at 100 Hz, with less than 3 mm positional error increase [40, 73]. Action chunking further abstracts multi‐step routines into single tokens (e.g. “pick‐and‐place‐cup”), cutting inference steps by up to 40% in long‐horizon tasks like kitchen workflows [25].

- Reinforcement Learning–Supervised Hybrid Training. The iRe‐VLA framework alternates between reinforcement learning (RL) in simulation and supervised fine‐tuning on human demonstrations to stabilize policy updates. By leveraging Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) to shape reward models and Conservative Q‐Learning to avoid extrapolation error, iRe‐VLA reduces sample complexity by 60% versus pure RL, while maintaining the semantic fidelity imparted by language‐conditioned priors [98, 102]. This hybrid approach yields robust policies for tasks with sparse feedback, such as dynamic obstacle avoidance.

- Hardware‐Aware Optimizations. Compiler‐level graph rewrites and kernel fusion (e.g. via NVIDIA TensorRT‐LLM) exploit target hardware features—tensor cores, fused attention, and pipelined memory transfers—to accelerate both transformer inference and diffusion sampling. In OpenVLA‐OFT, such optimizations reduced inference latency by 30% on RTX A2000 GPUs and lowered energy per inference by 25% compared to standard PyTorch execution [69]. This makes real‐time VLAs feasible on mobile robots and drones with strict power budgets.

- LoRA and quantization empower smaller labs to fine‐tune and operate billion‐parameter VLAs on consumer‐grade hardware, unlocking cutting‐edge semantic understanding for robots [118, 70].

- Pruning and FAST tokenization compress model and action representations, enabling sub‐4 GB, sub‐5 ms control loops without sacrificing precision in dexterous tasks [135, 86].

- Parallel decoding and action chunking overcome sequential bottlenecks of autoregressive policies, supporting 100–200 Hz decision rates needed for agile manipulation and legged locomotion [40, 73].

- Hybrid RL‐SL training stabilizes exploration in complex environments, while hardware‐aware compilation ensures real‐time performance on edge accelerators [98, 69].

3.4. Applications of Vision-Language-Action Models

3.4.1. Humanoid Robotics

3.4.2. Autonomous Vehicle Systems

3.4.3. Industrial Robotics

3.4.4. Healthcare and Medical Robotics

3.4.5. Precision and Automated Agriculture

3.4.6. Interactive AR Navigation with Vision-Language-Action Models

4. Challenges and Limitations of Vision-Language-Action Models

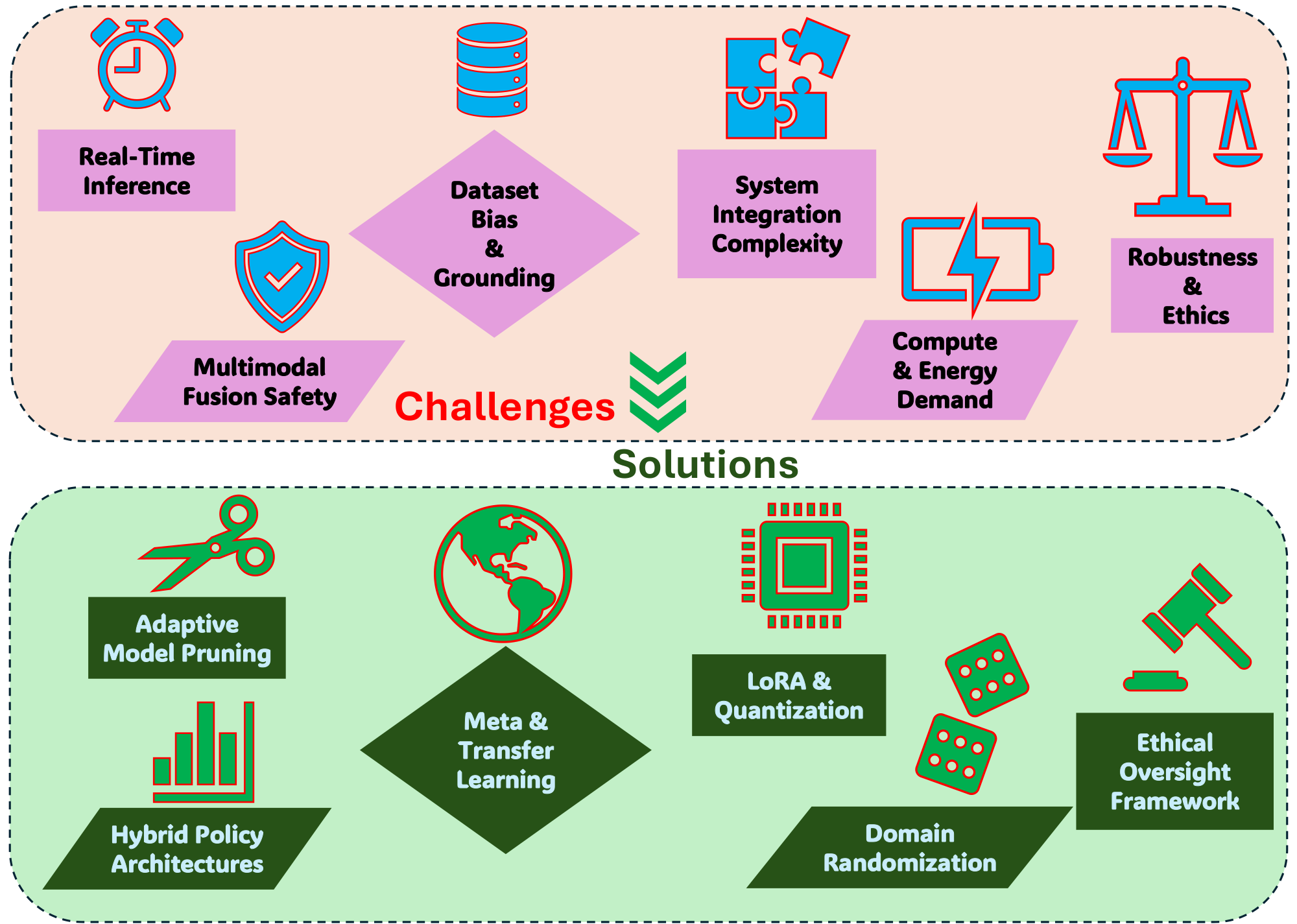

In this section, Vision-Language-Action models confront critical barriers preventing their transition from research prototypes to reliable real-world systems. Real-time inference remains constrained by autoregressive decoding that achieves only 3–5 Hz, far below the 100+ Hz required for precise robotic control, while memory demands exceed embedded hardware capabilities. Multimodal action representation struggles with discrete tokenization imprecision and diffusion-based computational overhead, and safety mechanisms introduce dangerous 200–500 ms latencies in dynamic environments. Dataset bias pervades training corpora, causing 23% object reference failures in novel settings and 40% performance drops on unseen tasks due to overfitting. System integration complexity arises from temporal mismatches between high-level planning (800 ms) and low-level control (10 ms), alongside feature space misalignments that degrade sim-to-real transfer by 32%. Energy demands of 7-billion-parameter models exceed edge device capacity, while environmental variability reduces vision accuracy by 20–30% under poor lighting and occlusion, compounded by ethical concerns regarding privacy and bias propagation.

4.1. Real-Time Inference Constraints

4.2. Multimodal Action Representation and Safety Assurance

4.3. Dataset Bias, Grounding, and Generalization to Unseen Tasks

4.4. System Integration Complexity and Computational Demands

4.5. Robustness and Ethical Challenges in VLA Deployment

5. Discussion

In this section, VLA models are shown to face six major challenges spanning real-time inference limitations, multimodal action representation and safety vulnerabilities, dataset bias and grounding errors, system integration complexity, computational demands, and robustness alongside ethical concerns, all of which collectively hinder practical deployment in real-world robotics and autonomous systems. To address these barriers, the discussion proposes targeted solutions including hardware accelerators and model compression techniques like LoRA and quantization to achieve sub-50 ms inference, hybrid policy architectures combining diffusion-based sampling with autoregressive planners for safe multimodal action representation, curated debiased datasets with meta-learning and sim-to-real fine-tuning for improved generalization, hardware-software co-design with modular adapters for efficient system integration, and domain randomization coupled with bias auditing and privacy-preserving inference to ensure robustness and ethical deployment. The future roadmap envisions VLAs evolving into generalist robotic intelligence through multimodal foundation models, agentic lifelong learning, hierarchical neuro-symbolic planning, real-time world models, cross-embodiment transfer, and built-in safety alignment, ultimately enabling human-centered, adaptable, and AGI-capable embodied agents.

5.1. Potential Solutions

- Real-Time Inference Constraints. Future research must develop VLA architectures that harmonize latency, throughput, and task-specific accuracy. One promising direction is the integration of specialized hardware accelerators—such as FPGA-based vision processors and tensor cores optimized for sparse matrix operations—to execute convolutional and transformer layers at sub-millisecond scales [70, 39]. Model compression techniques like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [118] and knowledge distillation can shrink parameter counts by up to 90%, reducing both memory footprint and inference time while retaining over 95% of original performance on benchmark tasks. Progressive quantization strategies that combine mixed-precision arithmetic (e.g., FP16/INT8) with block-wise calibration can further cut computation by 2–4× with minimal accuracy loss [69]. Adaptive inference architectures that dynamically adjust network depth or width based on input complexity—akin to early-exit branches in DeeR-VLA [29]—can reduce average compute by selectively bypassing transformer layers when visual scenes or linguistic commands are simple. Finally, efficient tokenization schemes leveraging subword patch embeddings and dynamic vocabulary allocation can compress visual and linguistic input into compact representations, minimizing token counts without sacrificing semantic richness [86]. Together, these innovations can enable sub-50 ms end-to-end inference on commodity edge GPUs, paving the way for latency-sensitive applications in autonomous drone flight, real-time teleoperation, and collaborative manufacturing.

- Multimodal Action Representation and Safety Assurance. Addressing multimodal action representation and robust safety requires end-to-end frameworks that unify perception, reasoning, and control under stringent safety constraints. Hybrid policy architectures combining diffusion-based sampling for low-level motion primitives [26] with autoregressive high-level planners [65] enable compact stochastic representations of diverse action trajectories, improving adaptability in dynamic environments. Safety can be enforced via real-time risk assessment modules that ingest multi-sensor fusion streams—visual, depth, and proprioceptive data—to predict collision probability and joint stress thresholds, triggering emergency stop circuits when predefined safety envelopes are breached [194, 195]. Reinforcement learning algorithms augmented with constrained optimization (e.g., Lagrangian methods in SafeVLA [35]) can learn policies that maximize task success while strictly respecting safety constraints. Online model adaptation techniques—such as rule-based RL (GRPO) and Direct Preference Optimization (DPO)—further refine action selection under new environmental conditions, ensuring consistent safety performance across scenarios [196]. Crucially, embedding formal verification layers that symbolically analyze planner outputs before execution can guarantee compliance with safety invariants, even for neural-network–based controllers. Integrating these methodologies will produce VLA systems that not only execute complex, multimodal actions but do so with provable safety in unstructured, real-world settings.

- Dataset Bias, Grounding, and Generalization to Unseen Tasks. Robust generalization demands both broadened data diversity and advanced learning paradigms. Curating large-scale, debiased multimodal datasets—combining web-scale image–text corpora like LAION-5B [116] with robot-centric trajectory archives such as Open X-Embodiment [97]—lays the groundwork for equitable semantic grounding. Hard-negative sampling and contrastive fine-tuning of vision–language backbones (e.g., CLIP variants) can mitigate spurious correlations and enhance semantic fidelity [64, 79]. Meta-learning frameworks enable rapid adaptation to novel tasks by learning shared priors across task families, as demonstrated in vision-language robotic navigation models [46]. Continual learning algorithms—with replay buffers and regularization strategies—preserve old knowledge while integrating new concepts, addressing catastrophic forgetting in VLA models [31]. Transfer learning from 3D perception domains (e.g., point cloud reasoning in 3D-VLA [104]) can imbue models with spatial inductive biases, improving out-of-distribution robustness. Finally, simulation-to-real (sim2real) fine-tuning with domain randomization and real-world calibration—such as dynamic lighting, texture, and physics variations—ensures that policies learned in synthetic environments transfer effectively to physical robots [203, 204]. These combined strategies will empower VLAs to generalize confidently to unseen objects, scenes, and tasks in real-world deployments.

- System Integration Complexity and Computational Demands. To manage the intricate orchestration of multimodal pipelines under tight compute budgets, researchers must embrace model modularization and hardware–software co–design. Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) adapters can be injected into pre–trained transformer layers, enabling task-specific fine–tuning without modifying core weights [118]. Knowledge distillation from large “teacher” VLAs into lightweight “student” networks—using student–teacher mutual information objectives—yields compact models with 5–10× fewer parameters while retaining 90–95% [69]. Mixed-precision quantization augmented by quantization-aware training can compress weights to 4–8 bits, cutting memory bandwidth and energy consumption by over 60% [70]. Hardware accelerators tailored for VLA workloads—supporting sparse tensor operations, dynamic token routing, and fused vision–language kernels—can deliver sustained 100+ TOPS throughput within a 20–30 W power envelope, meeting the demands of embedded robotic platforms [86, 65]. Toolchains like TensorRT-LLM [39] and TVM can optimize end-to-end VLA graphs for specific edge devices, fusing layers and precomputing static subgraphs. Emerging architectures such as TinyVLA demonstrate that sub-1B parameter VLAs can achieve near–state-of-the-art performance on manipulation benchmarks with real–time inference, charting a path for widespread deployment in resource-constrained settings.

- Robustness and Ethical Challenges in VLA Deployment. Ensuring VLA robustness and ethical integrity requires both technical and governance measures. Domain randomization and synthetic augmentation pipelines—like UniSim’s closed–loop sensor simulator—generate photorealistic variations in lighting, occlusion, and sensor noise, enhancing model resilience to environmental shifts [117]. Adaptive recalibration modules, which adjust perception thresholds and control gains based on real-time feedback, further mitigate drift and sensor degradation over prolonged operation. On the ethical front, bias auditing tools must scan training datasets for skewed demographic or semantic distributions, followed by corrective fine-tuning using adversarial debiasing and counterfactual augmentation [197, 79]. Privacy-preserving inferencing—via on–device processing, homomorphic encryption for sensitive data streams, and differential privacy during training—safeguards user data in applications like healthcare and smart homes [214, 215]. Socioeconomic impacts can be managed through transparent impact assessments and stakeholder engagement, ensuring that VLA adoption complements human labor through upskilling programs rather than displacing workers en masse. Finally, establishing regulatory frameworks and industry standards for VLA safety and accountability will underpin responsible innovation, balancing technical capabilities with societal values.

5.2. Future Roadmap

- Multimodal Foundation Models as the “Cortex.” Today’s VLAs typically couple a vision-language backbone with task-specific policy heads. Tomorrow, we expect a single, massive multimodal foundation model—trained on web-scale image, video, text, and affordance data—to serve as a shared perceptual and conceptual “cortex.” This foundation will encode not only static scenes but also dynamics, physics, and common-sense world knowledge, enabling downstream action learners to tap into a unified representational substrate rather than reinventing basic perceptual skills for every robot or domain.

- Agentic, Self-Supervised Lifelong Learning. Rather than static pretraining, future VLAs will engage in continual, self-supervised interaction with their environments. Agentic frameworks—where the model generates its own exploration objectives, hypothesizes outcomes, and self-corrects via simulated or real rollouts—will drive rapid skill acquisition. By formulating internal sub-goals (“learn to open drawers, ” “map furniture affordances”) and integrating reinforcement-style feedback, a VLA-driven humanoid could autonomously expand its capabilities over years of deployment, much like a human apprentice.

- Hierarchical, Neuro-Symbolic Planning. To scale from low-level motor primitives to high-level reasoning, VLAs will adopt hierarchical control architectures. A top-level language-grounded planner (perhaps an LLM variant fine-tuned for affordance reasoning) will decompose complex instructions (“prepare a cup of tea”) into sequences of sub-tasks (“fetch kettle, ” “fill water, ” “heat water, ” “steep tea bag”). Mid-level modules will translate these into parameterized motion plans, and low-level diffusion or transformer-based controllers will generate smooth, compliant trajectories in real time. This neuro-symbolic blend ensures both the interpretability of structured plans and the flexibility of learned policies.

- Real-Time Adaptation via World Models. Robustness in unstructured settings demands that VLAs maintain an internal, predictive world model—an up-to-date simulation of objects, contacts, and agent dynamics. As the robot acts, it will continuously reconcile its predictions with sensor feedback, using model-based corrective actions when discrepancies arise (e.g., slipping grasp). Advances in differentiable physics and video-to-state encoders will make these world models both accurate and efficient enough for on-board, real-time use. Cross-Embodiment and Transfer Learning: The era of training separate VLAs for each robot morphology will give way to embodiment-agnostic policies. By encoding actions in an abstract, kinematic-agnostic space (e.g., “apply grasp force at these affordance points”), future VLAs will transfer skills seamlessly between wheeled platforms, quadrupeds, and humanoids. Combined with meta-learning, a new robot can bootstrap prior skills with only a few minutes of calibration data. Safety, Ethics, and Human-Centered Alignment As VLAs gain autonomy, built-in safety and value alignment become non-negotiable. Future systems will integrate real-time risk estimators—assessing potential harm to humans or property before executing high-risk maneuvers—and seek natural language consent for ambiguous situations. Regulatory constraints and socially aware policies will be baked into the VLA stack, ensuring that robots defer to human preferences and legal norms.

6. Conclusion

In this section, the authors synthesize a comprehensive three-year review of Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models, tracing their evolution from isolated perception-action modules to unified, instruction-following robotic agents capable of integrating visual perception, natural language understanding, and physical action generation. The review systematically examines foundational concepts, tokenization strategies, learning paradigms—including supervised, imitation, and reinforcement learning—and architectural innovations across over 50 recent models, while addressing adaptive control, real-time execution, and deployment across six application domains: humanoid robotics, autonomous vehicles, industrial automation, healthcare, agriculture, and augmented reality navigation. Critical challenges are identified in real-time inference, safety assurance, bias mitigation, system integration, and ethical deployment, with proposed solutions encompassing model compression, cross-modal grounding, and agentic learning frameworks. The conclusion envisions VLA advancement as a convergence of vision-language models, adaptive architectures, and agentic AI systems, steering embodied robotics toward artificial general intelligence through intelligent, human-aligned, and contextually aware agents.

Acknowledgement

In this section, the authors acknowledge the financial support that enabled the research presented in the document. The work was funded by two major sources: the National Science Foundation and the United States Department of Agriculture's National Institute of Food and Agriculture. This support came through the Artificial Intelligence Institute for Agriculture Program, specifically under two awards—AWD003473 and AWD004595, with Accession Number 1029004. The funding was designated for a project titled "Robotic Blossom Thinning with Soft Manipulators," which aligns with the broader vision-language-action model research discussed throughout the document, particularly its application to agricultural robotics. This acknowledgment underscores the institutional backing necessary for advancing embodied AI systems capable of performing complex, real-world tasks in agricultural settings, thereby connecting foundational research in VLA models to practical, funded initiatives addressing industry-specific challenges.

Declarations

In this section, the authors provide a formal declaration of conflicts of interest, stating that none exist in relation to the research presented in this comprehensive review of vision-language-action models. This declaration serves as a standard ethical disclosure required in academic publications to ensure transparency and maintain the integrity of the research process. By explicitly confirming the absence of any financial, professional, or personal interests that could influence or appear to influence the work, the authors establish that the review was conducted without bias or external pressures that might compromise the objectivity of their analysis, findings, or recommendations regarding VLA model developments, applications, and future directions in embodied AI and robotic systems.

Statement on AI Writing Assistance

In this section, the authors disclose their use of AI writing tools to enhance the manuscript's linguistic quality and visual presentation. ChatGPT and Perplexity were employed to improve grammatical accuracy and refine sentence structure, with all AI-generated revisions subject to thorough human review and editing to ensure relevance and correctness. Additionally, ChatGPT-4o was utilized to generate realistic visualizations that support the document's technical content. This transparent acknowledgment establishes that while AI tools assisted in polishing language and creating illustrative figures, the substantive intellectual contributions, technical analysis, and scientific integrity of the work remain entirely under human oversight, ensuring that AI-generated content serves only as a refinement layer rather than a replacement for expert judgment and domain knowledge.

References

arXiv:2505.03233. %Type = ArticlearXiv:2505.02152. %Type = Inproceedings