AlphaEdit: Null-Space Constrained Knowledge Editing for Language Models

Show me an executive summary.

Purpose and context

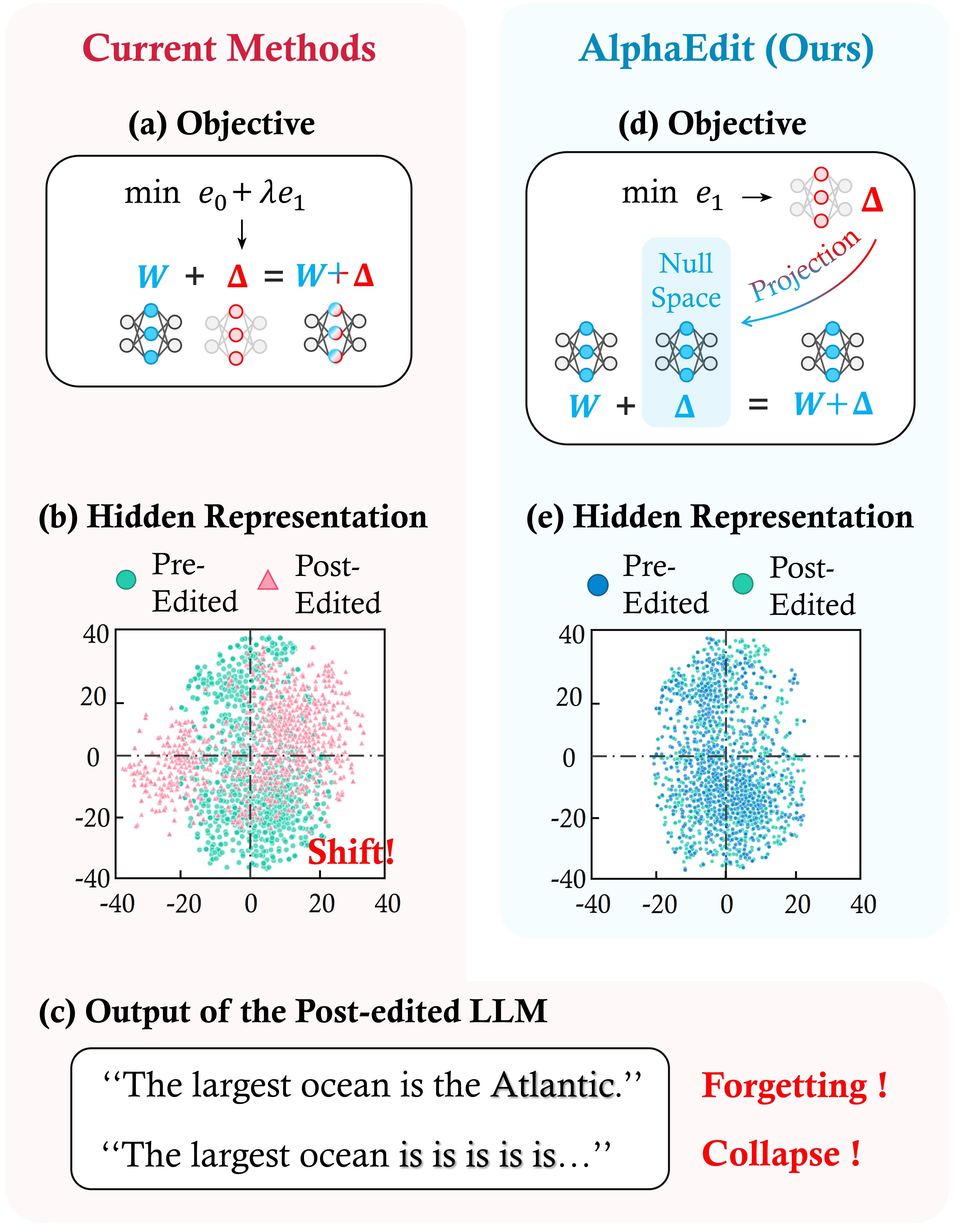

Large language models often store incorrect or outdated knowledge and produce hallucinations. Existing model editing methods that update this knowledge struggle to balance two competing goals: successfully updating target facts while preserving the model's other knowledge and general capabilities. Current approaches incorporate both objectives into their loss functions, but this trade-off causes the edited models to overfit to new knowledge, gradually degrading performance as sequential edits accumulate. This degradation manifests as model forgetting and, eventually, model collapse—where the model loses coherence and can no longer generate fluent text.

What was done

We developed AlphaEdit, a model editing method that resolves the update-preservation trade-off by projecting parameter changes onto the null space of preserved knowledge before applying them. The null space projection ensures that preserved knowledge remains mathematically unchanged after editing, allowing the optimization to focus solely on inserting new facts without compromise. We tested AlphaEdit on three widely-used language models (LLaMA3-8B, GPT-J-6B, GPT2-XL-1.5B) across two standard editing benchmarks (Counterfact and ZsRE), performing sequential editing tasks with up to 3,000 knowledge updates. We compared AlphaEdit against seven existing editing methods and evaluated both editing success and retention of general capabilities across six natural language understanding tasks.

Key findings

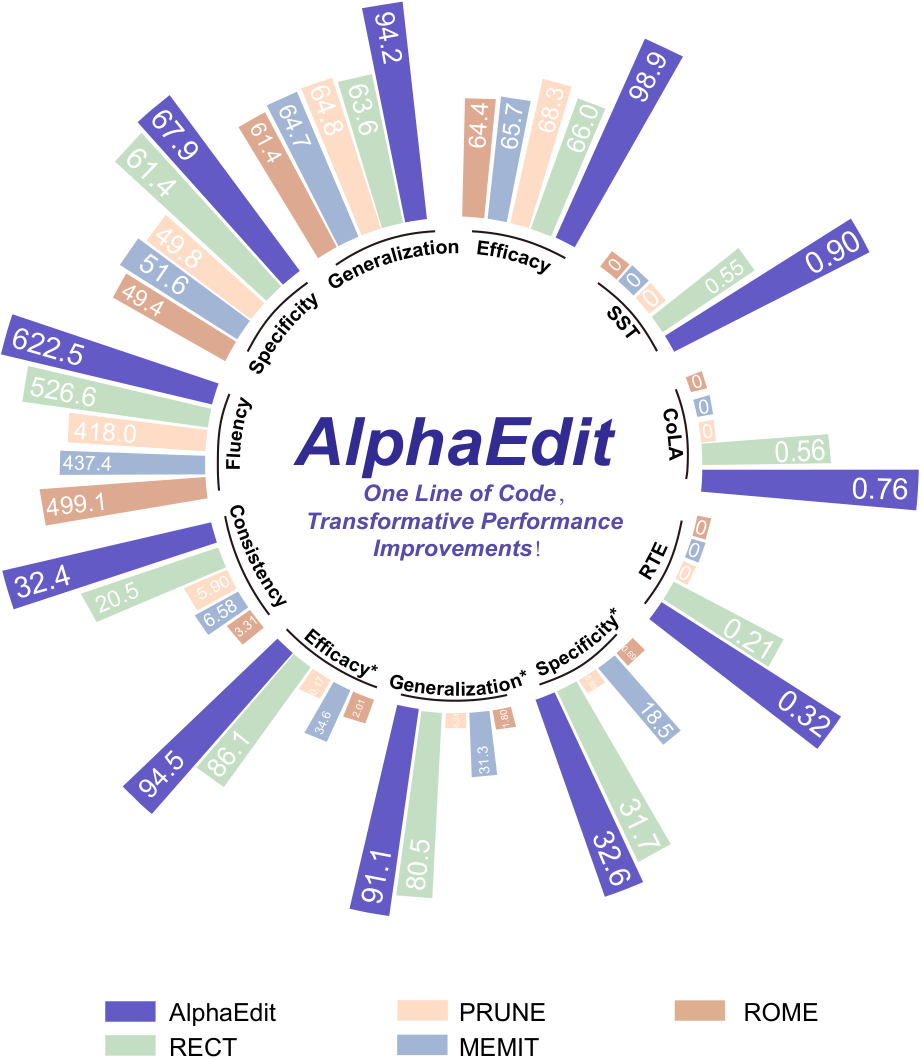

AlphaEdit achieves an average performance improvement of 36.7% over the best baseline methods across all metrics and models. On LLaMA3, the gains are particularly pronounced: efficacy improves by 32.85% and generalization by 30.60% compared to the strongest competitor. Critically, AlphaEdit maintains the model's general capabilities (sentiment analysis, paraphrase detection, language understanding, textual entailment, grammatical acceptability, natural language inference) at near-original levels even after 3,000 edits, while baseline methods collapse to near-zero performance after 2,000 edits. Analysis of hidden representations confirms that baseline methods cause significant distribution shift—indicating overfitting to updated knowledge—whereas AlphaEdit preserves the original distribution, preventing both forgetting and collapse.

What the results mean

These findings demonstrate that the null space projection approach fundamentally solves the preservation-update trade-off that limits current editing methods. The performance gains are substantial enough to enable practical sequential editing at scale, which is essential for maintaining accurate, up-to-date models in production environments. The ability to maintain general capabilities during extensive editing reduces the risk of model degradation and the associated costs of retraining or deploying multiple specialized models. The minimal computational overhead (effectively zero additional runtime compared to baselines) means AlphaEdit can be adopted without infrastructure changes.

Recommendations and next steps

Integrate AlphaEdit's null space projection into existing model editing pipelines. The method requires only a single line of additional code and functions as a plug-in enhancement for most current editing approaches (MEMIT, PRUNE, RECT). For organizations performing regular knowledge updates, adopt AlphaEdit as the standard editing method to prevent long-term model degradation. Prioritize deployment on models undergoing frequent updates where cumulative editing effects are most severe. For development teams, consider extending AlphaEdit to multi-modal models and large reasoning models, which remain untested. If editing fewer than 500 facts in isolation, baseline methods may suffice; for sequential editing scenarios or when general capability preservation is critical, AlphaEdit is strongly recommended.

Limitations and confidence

The method has been validated only on text-based transformer models; applicability to vision-language models and reasoning-focused architectures is unknown. The null space projection requires computing a projection matrix from a sample of preserved knowledge (typically 100,000 Wikipedia triplets); performance degrades if this sample is too small or unrepresentative, with specificity dropping by approximately 12% when using only 10% of the standard dataset size. The method does not address editing of multi-hop reasoning chains or complex relational updates tested in MQuAKE; while AlphaEdit shows improvements on these benchmarks, performance remains modest. Confidence in the core results is high—effects are consistent across three different model families, two datasets, and multiple metrics with statistical significance confirmed through repeated trials. The main uncertainty concerns generalization beyond the tested model architectures and knowledge types.

Junfeng Fang1,2^{1,2}1,2* , Houcheng Jiang1 ∗^{1 \, *}1∗, Kun Wang1^{1}1, Yunshan Ma2^{2}2, Jie Shi2^{2}2, Xiang Wang1†^{1 \dagger}1† , Xiangnan He1†^{1 \dagger}1†, Tat-Seng Chua2^{2}2

1^11University of Science and Technology of China, 2^22National University of Singapore

* Equal contribution. †^{ \dagger}†Corresponding author: {xiangwang1223, xiangnanhe}@gmail.com.

Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) often exhibit hallucinations, producing incorrect or outdated knowledge. Hence, model editing methods have emerged to enable targeted knowledge updates. To achieve this, a prevailing paradigm is the locating-then-editing approach, which first locates influential parameters and then edits them by introducing a perturbation. While effective, current studies have demonstrated that this perturbation inevitably disrupt the originally preserved knowledge within LLMs, especially in sequential editing scenarios. To address this, we introduce AlphaEdit, a novel solution that projects perturbation onto the null space of the preserved knowledge before applying it to the parameters. We theoretically prove that this projection ensures the output of post-edited LLMs remains unchanged when queried about the preserved knowledge, thereby mitigating the issue of disruption. Extensive experiments on various LLMs, including LLaMA3, GPT2-XL, and GPT-J, show that AlphaEdit boosts the performance of most locating-then-editing methods by an average of

36.7%36.7\%36.7% with

a single line of additional code for projection solely. Our code is available at:

https://github.com/jianghoucheng/AlphaEdit.

1. Introduction

In this section, the authors address the problem that large language models frequently hallucinate by producing incorrect or outdated knowledge, necessitating targeted knowledge updates through model editing methods. While current parameter-modifying approaches follow a locate-then-edit paradigm—first identifying influential parameters and then perturbing them—these methods struggle to balance preserving existing knowledge while updating target knowledge, especially during sequential editing where multiple edits accumulate. This imbalance causes the model to overfit to updated knowledge, shifting the distribution of hidden representations and ultimately leading to model forgetting and collapse. To solve this, AlphaEdit removes the preservation error term from the objective function and instead projects the perturbation onto the null space of preserved knowledge before applying it to parameters, mathematically guaranteeing that preserved knowledge remains intact. Extensive experiments on LLaMA3, GPT2-XL, and GPT-J demonstrate that AlphaEdit boosts existing methods' performance by an average of 36.7% with only a single line of additional code, establishing it as a plug-and-play enhancement for efficient knowledge updates in LLMs.

Large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated the capability to store extensive knowledge during pre-training and recall it during inference ([1, 2, 3, 4]). Despite this, they frequently exhibit hallucinations, producing incorrect or outdated information ([5, 6]). While fine-tuning with updated knowledge offers a straightforward solution, it is often prohibitively time-consuming ([7]). In sight of this, model editing methods have emerged, enabling updating the target knowledge while preserving other knowledge ([8, 9]). Broadly, model editing approaches fall into two categories: (1) parameter-modifying methods, which directly adjust a small subset of parameters ([10, 11]), and (2) parameter-preserving methods that integrate additional modules without altering the original parameters ([12, 13, 14, 15]).

In this paper, we aim to explore the parameter-modifying methods for model editing. Concretely, current parameter-modifying methods typically follow the locate-then-edit paradigm ([16]). The basic idea is to first locate influential parameters W {\bm{W}}W through causal tracing, and then edit them by introducing a perturbation Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ ([17]). The common objective for solving Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ is to minimize the output error on the to-be-updated knowledge, denoted as e1e_1e1. Additionally, the output error on the to-be-preserved knowledge, e0e_0e0, is typically incorporated into the objective function, acting as a constraint to ensure the model’s accuracy on the preserved knowledge.

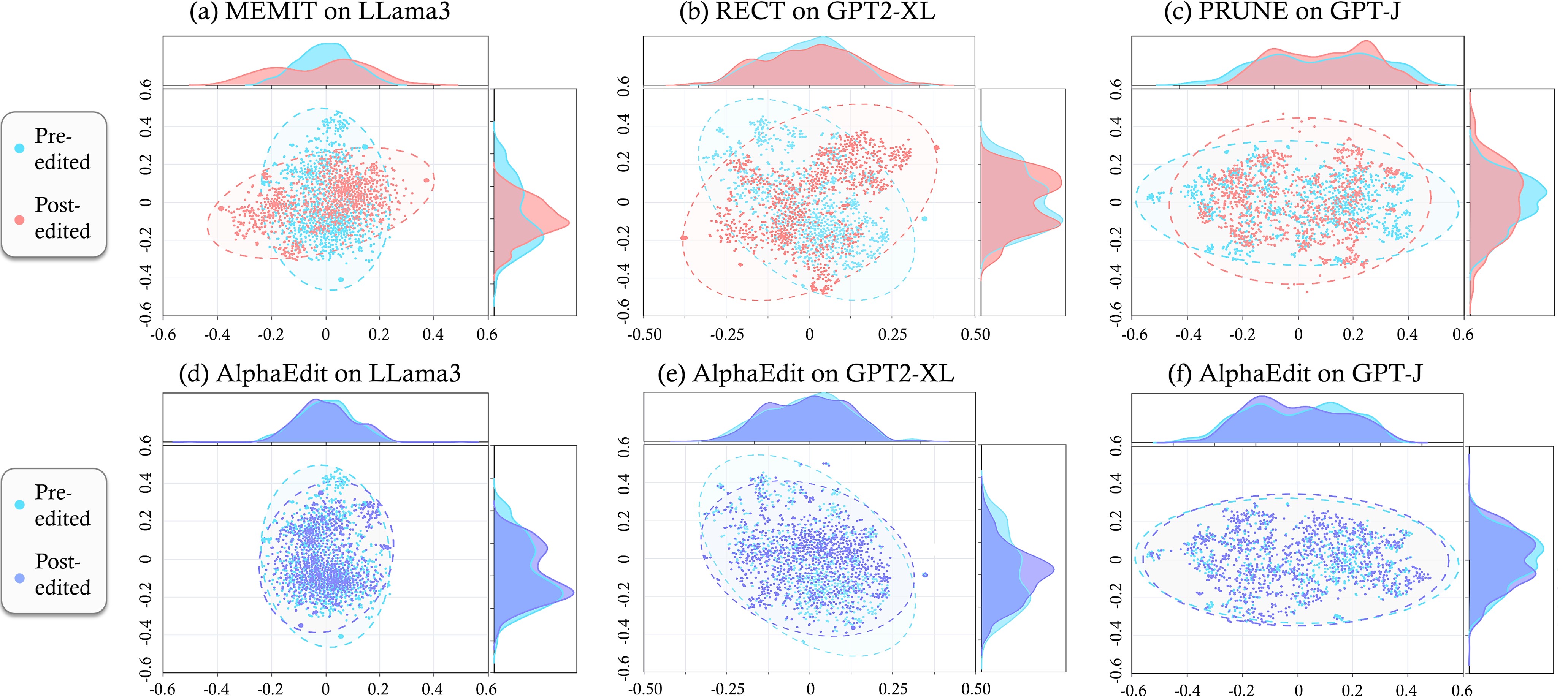

Despite their success, the current paradigm faces a critical limitation: it struggles to maintain a balance between knowledge-update error e1e_1e1 and knowledge-preservation error e0e_0e0. Specifically, to prioritize the success of update, prior studies focus more on minimizing e1e_1e1 by assigning a larger weight, while taking insufficient control over e0e_0e0. This could make the LLMs after editing (i.e., the post-edited LLMs) overfit to the updated knowledge. This overfitting would introduce a distribution shift of the hidden representations within LLMs. Figure 1 (b) showcases this shift, where the hidden representations in the post-edited LLaMA-3 (8B) ([18]) diverge from their distribution in the original LLM (i.e., the pre-edited LLM). Worse still, in sequential editing scenarios ([19]) where the LLM undergoes multiple sequential edits, the accumulation of overfitting gradually erodes the model's ability to preserve knowledge and generate coherent sentences, eventually leading to model forgetting and model collapse, as depicted in Figure 1 (c).

To address these flaws, we instead remove e0e_0e0 from the current objective, allowing the model to focus solely on minimizing e1e_1e1 without trade-offs. To avoid overfitting to the to-be-updated knowledge, we project the solution of this new objective onto the null space ([20]) of the preserved knowledge before applying it to the model parameters, as shown in Figure 1 (d). By leveraging the mathematical properties of matrix projection and null space, our new objective ensures that the distribution of hidden representations within LLMs remains invariant post-edited, as shown in Figure 1 (e). This invariance enables the post-edited LLMs to reduce e1e_1e1 while keeping e0e_0e0 close to zero, thereby alleviating the issues of model forgetting and model collapse. A detailed theoretical proof is provided in Section 3. In a nutshell, we term the method as AlphaEdit, a simple yet effective editing approach with a null-space constraint for LLMs.

To validate the effectiveness of our method, we conducted extensive experiments on multiple representative LLMs, such as GPT-2 XL ([21]) and LLaMA-3 (8B). The results show that, compared to the best-performing baseline methods, AlphaEdit can achieve over a 36.7% performance improvement on average by adding just one line of code to the conventional model editing method, MEMIT ([10]), as illustrated in Figure 2. Furthermore, we empirically verified that this simple optimization can be easily integrated into most existing model editing methods ([22, 23]), functioning as a plug-and-play enhancement that significantly boosts their performance. This highlights AlphaEdit's crucial role in efficient knowledge updates for LLMs, enabling broader applications and future advancements in the field.

2. Preliminary

In this section, the foundational concepts for model editing in large language models are established by first describing how autoregressive LLMs predict the next token based on preceding context through hidden states computed across layers, where feed-forward network layers—specifically the output weight matrix—function as linear associative memory that stores knowledge as key-value pairs mapping subject-relation inputs to object outputs. Building on this interpretation, model editing methods follow a locate-then-edit paradigm that modifies these FFN parameters by introducing a perturbation to update knowledge while preserving existing information. The editing objective minimizes both the error on to-be-updated knowledge and the error on preserved knowledge, with the latter typically estimated from 100,000 Wikipedia triplets since direct access to the model's complete knowledge is infeasible. The closed-form solution combines these constraints through a normal equation that balances updating new associations against maintaining existing ones.

2.1 Autoregressive Language Model

An autoregressive large language model (LLM) predicts the next token x {\bm{x}}x in a sequence based on the preceding tokens. Specifically, the hidden state of x {\bm{x}}x at layer lll within the model, denoted as hl {\bm{h}}^lhl, can be calculated as:

where al {\bm{a}}^lal and ml {\bm{m}}^lml represent the outputs of the attention block and the feed-forward network (FFN) layer, respectively; Winl {\bm{W}}_{\text{in}}^lWinl and Woutl {\bm{W}}_{\text{out}}^lWoutl are the weight matrices of the FFN layers; σ\sigmaσ is the non-linear activation function, and γ\gammaγ denotes the layer normalization. Following [16], we express the attention and FFN modules in parallel here.

It is worth noting that Woutl {\bm{W}}_{\text{out}}^lWoutl within FFN layers is often interpreted as a linear associative memory, functioning as key-value storage for information retrieval ([24]). Specifically, if the knowledge stored in LLMs is formalized as (s,r,o)(s, r, o)(s,r,o) — representing subject sss, relation rrr, and object ooo (e.g., s=“The latest Olympic Game”s=\text{``The latest Olympic Game''}s=“The latest Olympic Game”, r=“was held in”r=\text{``was held in''}r=“was held in”, o=“Paris”o=\text{``Paris''}o=“Paris”) — Woutl {\bm{W}}_{\text{out}}^lWoutl associates a set of input keys k {\bm{k}}k encoding (s,r)(s, r)(s,r) with corresponding values v {\bm{v}}v encoding (o)(o)(o). That is,

This interpretation has inspired most model editing methods to modify the FFN layers for knowledge updates ([25, 26, 27]). For simplicity, we use W {\bm{W}}W to refer to Woutl {\bm{W}}_{\text{out}}^lWoutl in the following sections.

2.2 Model Editing in LLMs

Model editing aims to update knowledge stored in LLMs through a single edit or multiple edits (i.e., sequential editing). Each edit modifies the model parameters W {\bm{W}}W by adding a perturbation Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ in locate-then-edit paradigm. Specifically, suppose each edit needs to update uuu pieces of knowledge in the form of (s,r,o)(s, r, o)(s,r,o). The perturbed W {\bm{W}}W is expected to associate uuu new k {\bm{k}}k- v {\bm{v}}v pairs, where k {\bm{k}}k and v {\bm{v}}v encode (s,r)(s, r)(s,r) and (o)(o)(o) of the new knowledge, respectively. Let W∈Rd1×d0 {\bm{W}} \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{1} \times d_{0}}W∈Rd1×d0, where d0d_0d0 and d1d_1d1 represent the dimensions of the FFN's intermediate and output layers. Then, we can stack these keys and values into matrices following:

where the subscripts of k {\bm{k}}k and v {\bm{v}}v represent the index of the to-be-updated knowledge. Based on these, the objective can be expressed as:

where ∥⋅∥2\left\| \cdot \right\|^2∥⋅∥2 denotes the sum of the squared elements in the matrix.

Additionally, let K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 and V0 {\bm{V}}_0V0 represent the matrices formed by stacking the k {\bm{k}}k and v {\bm{v}}v of the preserved knowledge. Current methods ([10, 23]) typically incorporate the error involving K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 and V0 {\bm{V}}_0V0 to preserve it, as follows:

Since K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 and V0 {\bm{V}}_0V0 encode the preserved knowledge in LLMs, we have WK0=V0 {\bm{W}} {\bm{K}}_0= {\bm{V}}_0WK0=V0 (cf. Eqn. 1). Thus, by applying the normal equation ([28]), if the closed-form solution of Eqn. 4 exists, it can be written as:

Although K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 is difficult to obtain directly since we hardly have access to the LLM's full extent of knowledge, it can be estimated using abundant text input ([10]). In practical applications, 100,000100, 000100,000 (s,r,o)(s, r, o)(s,r,o) triplets from Wikipedia are typically randomly selected to encode K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 ([10]), making K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 a high-dimensional matrix with 100,000100, 000100,000 columns (i.e., K0∈Rd0×100,000 {\bm{K}}_0\in \mathbb{R}^{d_{0} \times 100, 000}K0∈Rd0×100,000). See Appendix B.1 for detailed implementation steps.

3. Method

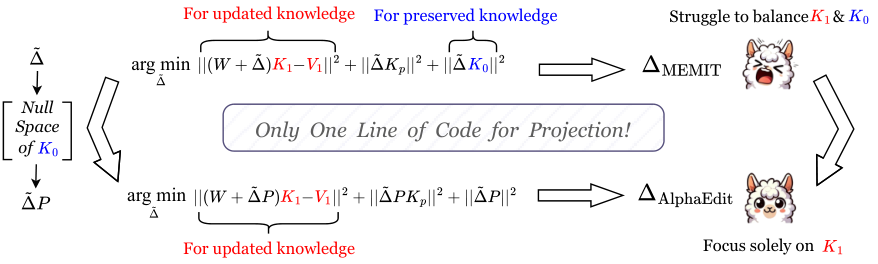

In this section, the authors address the fundamental problem that standard model editing methods struggle to balance updating target knowledge while preserving existing knowledge, leading to model forgetting and collapse in sequential editing scenarios. They introduce the concept of null space projection as the solution: by projecting the parameter perturbation onto the null space of the matrix encoding preserved knowledge, the post-edited model's outputs remain unchanged when queried about preserved information, mathematically guaranteeing protection. The projection matrix is computed via singular value decomposition of a covariance matrix, requiring only a single computation that can be reused across all editing tasks. This approach enables a reformulated optimization objective that eliminates the preservation error term entirely, allowing the model to focus solely on minimizing update error while the null space constraint inherently protects preserved knowledge. The result is a method requiring just one additional line of code that significantly boosts existing editing algorithms' performance with negligible computational overhead.

In this section, the appendix provides comprehensive implementation details and theoretical foundations for AlphaEdit's experimental framework, beginning with detailed descriptions of five datasets (Counterfact, ZsRE, KnowEdit, LEME, and MQuAKE) that measure editing efficacy, generalization, specificity, fluency, and consistency across different knowledge update scenarios. The evaluation metrics are formally defined for both ZsRE and Counterfact benchmarks, with specific formulations for measuring editing success through probability comparisons and entropy calculations. Implementation details specify layer-targeting strategies and hyperparameters for GPT-2 XL, GPT-J, and LLaMA3 models, while baseline methods including MEND, ROME, MEMIT, PRUNE, RECT, SERAC, MELO, and GRACE are characterized by their distinct approaches to model editing. Mathematical proofs establish that the projection matrix successfully maps parameter updates onto the null space of preserved knowledge representations, ensuring edits update target facts without degrading the model's retained capabilities, thereby validating AlphaEdit's theoretical framework for balancing knowledge modification with preservation.

In this section, we first introduce the concept of the null space and its relationship to model editing (Section 3.1). Based on this, we present the method for projecting a given perturbation Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ onto the null space of the matrix K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0, which encodes the persevered knowledge (Section 3.2). Following that, a new editing objective that incorporates the aforementioned projection method is introduced in Section 3.3.

3.1 Null Space

Null space is at the core of our work. Here we first introduce the definition of the left null space (hereafter referred to simply as null space). Specifically, given two matrices A {\bm{A}}A and B {\bm{B}}B, B {\bm{B}}B is in the null space of A {\bm{A}}A if and only if BA=0 {\bm{B}} {\bm{A}}=\bm{0}BA=0. See Adam-NSCL ([20]) for more details.

In the context of model editing, if the perturbation Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ is projected into the null space of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 (i.e., Δ′K0=0{\bm{\Delta}'} {\bm{K}}_0=\bm{0}Δ′K0=0, where Δ’\bm{\Delta}’Δ’ denotes the projected perturbation), adding it to the parameters W {\bm{W}}W results in:

This implies that the projected Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ will not disrupt the key-value associations of the preserved knowledge (i.e., {K0,V0}\{{\bm{K}}_0, {\bm{V}}_0\}{K0,V0}), ensuring that the storage of the preserved knowledge remains intact.

Therefore, in this work, before adding perturbation Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ to the model parameters W {\bm{W}}W, we project it onto the null space of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 to protect the preserved knowledge. This protection allows us to remove the first term — the term focusing on protecting the preserved knowledge — from the objective in Eqn. 4.

3.2 Null Space Projecting

In Section 3.1, we briefly explained why Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ should be projected into the null space of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0. In this part, we focus on how to implement this projection.

As introduced at the end of Section 2.2, the matrix K0∈Rd0×100,000 {\bm{K}}_0\in \mathbb{R}^{d_{0} \times 100, 000}K0∈Rd0×100,000 has a high dimensionality with 100,000100, 000100,000 columns. Hence, directly projecting the given perturbation Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ onto the null space of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 presents significant computational and storage challenges. In sight of this, we adopt the null space of the non-central covariance matrix K0K0T∈Rd0×d0 {\bm{K}}_0 {\bm{K}}_0^T\in \mathbb{R}^{d_{0} \times d_{0}}K0K0T∈Rd0×d0 as a substitute to reduce computational complexity, as d0d_{0}d0 is typically much smaller than 100,000100, 000100,000. This matrix's null space is equal to that of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 (please see Appendix B.2 for detailed proof).

Following the existing methods for conducting null space projection ([20]), we first apply a Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T:

where each column in U {\bm{U}}U is an eigenvector of K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T. Then, we remove the eigenvectors in U {\bm{U}}U that correspond to non-zero eigenvalues, and define the remaining submatrix as U^\hat{{\bm{U}}}U^. Based on this, the projection matrix P {\bm{P}}P can be defined as follows:

This projection matrix can map the column vectors of Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ into the null space of K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T, as it satisfies the condition ΔP⋅K0(K0)T=0\bm{\Delta} {\bm{P}} \cdot {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^T=\bm{0}ΔP⋅K0(K0)T=0. The detailed derivation is exhibited in Appendix B.3.

Since K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 and K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T share the same null space, we can derive ΔP⋅K0=0\bm{\Delta} {\bm{P}} \cdot {\bm{K}}_0 =\bm{0}ΔP⋅K0=0. Hence, we have:

This shows the projection matrix P {\bm{P}}P ensures that the model edits occur without interference with the preserved knowledge in LLMs.

3.3 Null-Space Constrained Model Editing

Section 3.2 has provided how to apply projection to ensure that preserved knowledge is not disrupted. Here, we introduce how to leverage this projection to optimize the current model editing objective.

Starting with the single-edit objective in Eqn. 4, the optimization follows three steps: (1) Replace Δ\bm{\Delta}Δ with the projected perturbation ΔP\bm{\Delta} {\bm{P}}ΔP, ensuring that the perturbation would not disrupt the preserved knowledge; (2) Remove the first term involving K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0, as Step (1) has already protected the preserved knowledge from being disrupted; (3) Add a regularization term ∣∣ΔP∣∣2||\bm{\Delta} {\bm{P}}||^2∣∣ΔP∣∣2 to guarantee stable convergence. With these optimizations, Eqn. 4 becomes:

where K1 {\bm{K}}_1K1 and V1 {\bm{V}}_1V1 denote the key and value matrices of to-be-updated knowledge defined in Eqn. 2.

In sequential editing tasks, during the current edit, we also need to add a term to the objective (cf. Eqn. 5) to prevent the perturbation from disrupting the updated knowledge in previous edits. Let Kp {\bm{K}}_pKp and Vp {\bm{V}}_pVp present the key and value matrices of the previously updated knowledge, analogous to the earlier definitions of K1 {\bm{K}}_1K1 and V1 {\bm{V}}_1V1. This term should minimize ∣∣(W+Δ~P)Kp−Vp∣∣2||({\bm{W}}+\bm{\tilde{\Delta}} {\bm{P}}) {\bm{K}}_p- {\bm{V}}_p||^2∣∣(W+Δ~P)Kp−Vp∣∣2 to protect the association. Since the related knowledge has been updated in previous edits, we have WKp=Vp {\bm{W}} {\bm{K}}_p= {\bm{V}}_pWKp=Vp. Hence, this term can be simplified to ∣∣Δ~PKp∣∣2||\bm{\tilde{\Delta}} {\bm{P}} {\bm{K}}_p||^2∣∣Δ~PKp∣∣2, and adding it to Eqn. 5 gives the new objective:

To facilitate expression, we define the residual vector of the current edit as R=V1−WK1 {\bm{R}} = {\bm{V}}_1 - {\bm{W}} {\bm{K}}_1R=V1−WK1. Based on this, Eqn. 6 can be solved using the normal equation ([28]):

Solving Eqn. 7 yields the final perturbation ΔAlphaEdit=ΔP\bm{{\Delta}}_{\textbf{AlphaEdit}}=\bm{\Delta} {\bm{P}}ΔAlphaEdit=ΔP which will be added to the model parameters W {\bm{W}}W:

The detailed derivation process and the invertibility of the term within the brackets are provided in Appendix B.4 and Appendix B.5 respectively. This solution ΔAlphaEdit\bm{{\Delta}}_{\textbf{AlphaEdit}}ΔAlphaEdit could not only store the to-be-updated knowledge in the current edit, but also ensure that both the preserved knowledge and the previously updated knowledge remain unaffected. Furthermore, for better comparison, we also present the commonly used solution in existing methods like MEMIT ([10]) as follows:

By comparing Eqn. 8 and 9, it is evident that our approach requires only a minor modification to the standard solution by incorporating the projection matrix P {\bm{P}}P. This makes our method easily integrable into existing model editing algorithms. Figure 3 summarizes this modification from the perspective of convergence objectives. We emphasize that by adding just a single line of code for this modification, the performance of most editing methods could be significantly enhanced, as shown in Figure 2. More detailed experimental results are exhibited in Section 4.

Furthermore, since the projection matrix P {\bm{P}}P is entirely independent of the to-be-updated knowledge, it only needs to be computed once and can then be directly applied to any downstream editing tasks. Consequently, AlphaEdit introduces negligible additional time consumption compared to baselines, making it both efficient and effective.

4. Experiment

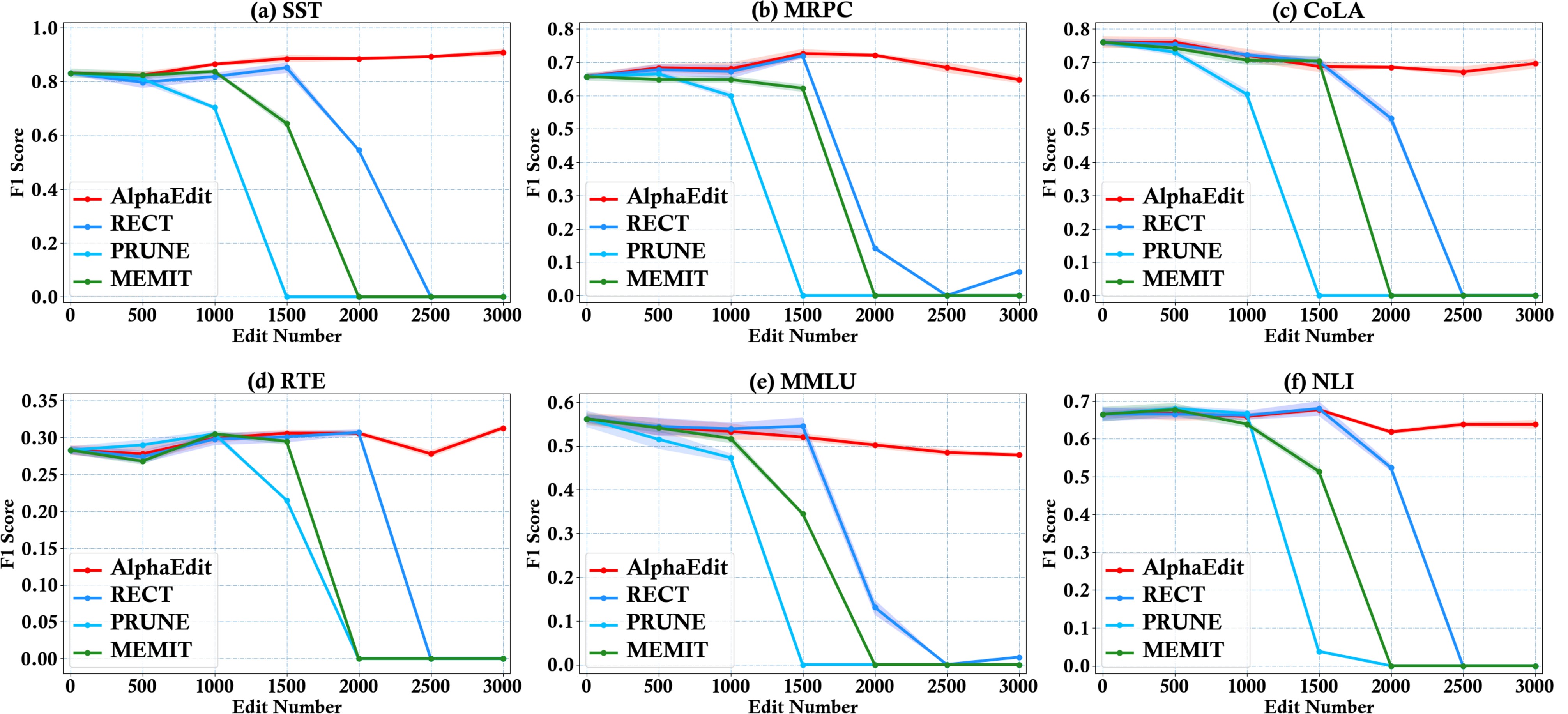

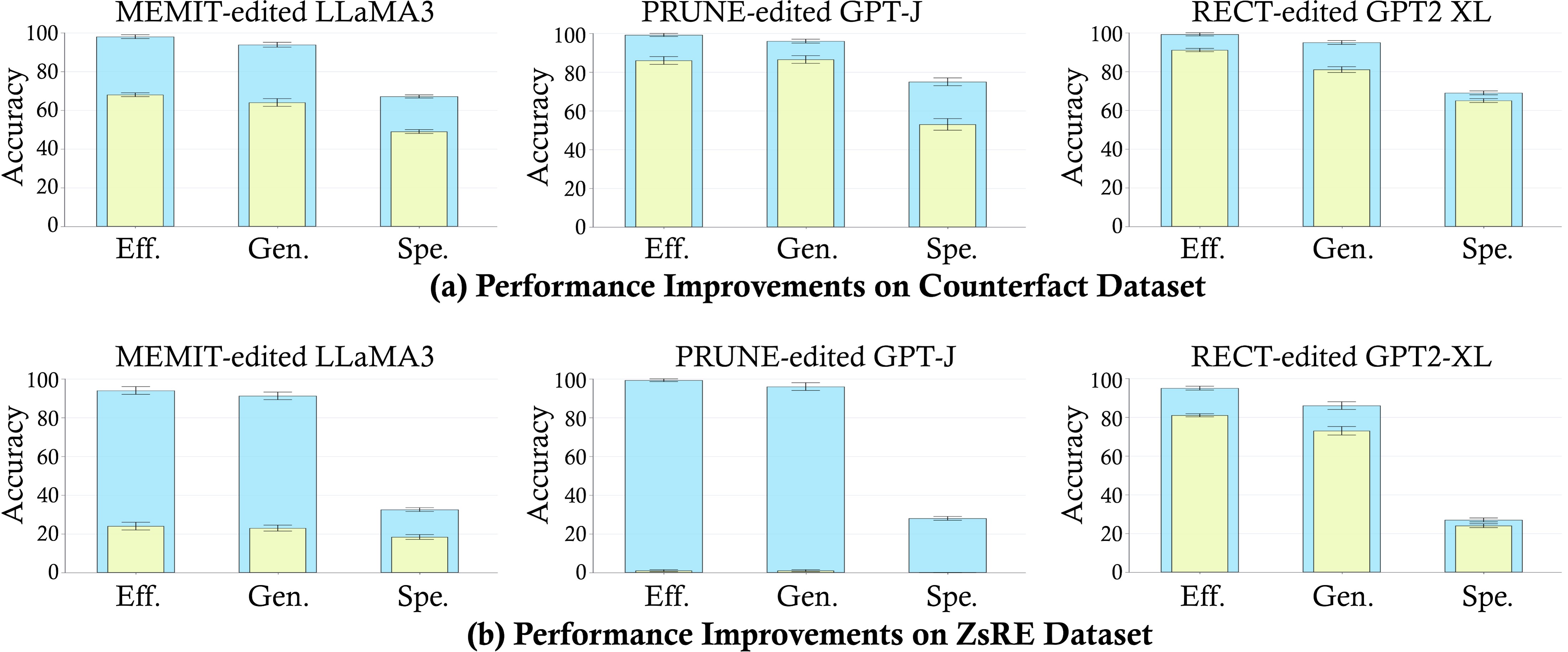

In this section, the authors evaluate AlphaEdit's performance on sequential model editing tasks across three language models (GPT2-XL, GPT-J, and LLaMA3) using Counterfact and ZsRE datasets, comparing it against seven baseline methods including MEMIT, ROME, and fine-tuning. AlphaEdit achieves superior results across nearly all metrics, providing average improvements of 12.54% in Efficacy and 16.78% in Generalization over the best baselines, with particularly dramatic gains on LLaMA3 (32.85% and 30.60% respectively). General capability tests on six GLUE benchmark tasks demonstrate that AlphaEdit preserves the model's original performance even after editing 3,000 samples, while baseline methods experience severe degradation after 2,000 edits. Hidden representation analysis using t-SNE visualization reveals that AlphaEdit maintains distributional consistency, preventing the overfitting that causes baseline methods to exhibit significant distributional shifts. Finally, ablation studies confirm that integrating AlphaEdit's null-space projection into existing methods requires only a single line of code yet yields substantial performance improvements averaging 28.24% on editing capability and 42.65% on general capability.

In this section, we conduct experiments to address the following research questions:

- RQ1: How does AlphaEdit perform on sequential editing tasks compared to baseline methods? Can it mitigate the issues of model forgetting and model collapse exhibited in Figure 1?

- RQ2: How does AlphaEdit-edited LLM perform on general ability evaluations? Does the post-edited LLM successfully retain its inherent capabilities?

- RQ3: Can AlphaEdit effectively prevent the model from overfitting to updated knowledge? Specifically, can the post-edited LLM avoid shifts in the distribution of hidden representations?

- RQ4: Can the performance of baseline methods be significantly improved with a single line of code in AlphaEdit (i.e., the code for projection)?

4.1 Experimental Setup

We begin by briefly outlining the evaluation metrics, datasets, and baseline methods. For more detailed descriptions of the experimental settings, please refer to Appendix A.

Base LLMs & Baseline Methods. Our experiments are conducted on three LLMs: GPT2-XL (1.5B), GPT-J (6B), and LLaMA3 (8B). We compare our method against several model editing baselines, including Fine-Tuning (FT) ([29]), MEND ([6]), InstructEdit ([30]), ROME ([16]), MEMIT ([10]), PRUNE ([22]), and RECT ([23]). Furthermore, to further validate the generalizability of AlphaEdit, we include three memory-based editing methods (i.e., SERAC ([7]), GRACE ([14]) and MELO ([13])) as baselines in Appendix C.5, along with two additional base LLMs: Gemma ([31]) and phi-1.5 ([32]) in Appendix C.6.

Datasets & Evaluation Metrics. We evaluate AlphaEdit using two widely adopted benchmarks: the Counterfact dataset ([16]) and the ZsRE dataset ([33]). In line with prior works ([16]), we employ Efficacy (efficiency success), Generalization (paraphrase success), Specificity (neighborhood success), Fluency (generation entropy), and Consistency (reference score) as evaluation metrics. In addition, for comprehensive evaluation, Appendix C.7 presents experiments conducted on three additional datasets: LongformEvaluation ([34]), MQUAKE ([35]), and KnowEdit ([36]). We encourage interested readers to refer to Appendix C.7 for further details.

4.2 Performance on Knowledge Update and Preservation (RQ1)

To evaluate the performance of different editing methods in terms of knowledge update and retention, we conducted sequential editing on three base LLMs using AlphaEdit and the baseline methods. Table 1 presents the results under a commonly used configuration for the sequential editing task, where 2, 000 samples are randomly drawn from the dataset for updates, with 100 samples per edit (i.e., a batch size of 100). For additional experimental results, such as case studies of model outputs after editing, please refer to Appendix C. Based on Table 1, we can draw the following observations:

- Obs 1: AlphaEdit achieves superior performance across nearly all metrics and base models. Specifically, in terms of Efficacy and Generalization metrics, AlphaEdit provides an average improvement of 12.54% and 16.78%, respectively, over the best baseline. On LLaMA3, these performance boosts are even more remarkable (*i.e., * 32.85%↑32.85\% \uparrow32.85%↑ and 30.60%↑30.60\% \uparrow30.60%↑). These gains arise from AlphaEdit’s ability to mitigate the trade-off between updating and preserving knowledge.

- Obs 2: AlphaEdit enhances text generation fluency and coherence.

In addition to editing capabilities, AlphaEdit also exhibits substantial improvements in Fluency and Coherence. For instance, on GPT2-XL, AlphaEdit achieves an 18.33%18.33\%18.33% improvement over the strongest baseline, demonstrating that it can preserve both the knowledge and the ability to generate fluent text.

4.3 General Capability Tests (RQ2)

To further evaluate the intrinsic knowledge of post-edited LLMs, we perform General Capability Tests using six natural language tasks from the General Language Understanding Evaluation (GLUE) benchmark ([37]). Specifically, the evaluation tasks include:

- 1. SST (The Stanford Sentiment Treebank) ([38]) is a single-sentence classification task involving sentences from movie reviews and their corresponding human-annotated sentiment labels. The task requires classifying the sentiment into two categories.

- 2. MRPC (Microsoft Research Paraphrase Corpus) ([39]) is a well-known benchmark for text matching and semantic similarity assessment. In the MRPC task, the objective is to determine whether a given pair of sentences is semantically equivalent.

- 3. MMLU (Massive Multi-task Language Understanding) ([40]) is a comprehensive evaluation designed to measure the multi-task accuracy of text models. This assessment focuses on evaluating models under zero-shot and few-shot settings.

- 4. RTE (Recognizing Textual Entailment) ([41]) involves natural language inference that determines if a premise sentence logically entails a hypothesis sentence.

- 5. CoLA (Corpus of Linguistic Acceptability) ([42]) is a single-sentence classification task, where sentences

are annotated as either grammatically acceptable or unacceptable.

- 6. NLI (Natural Language Inference) ([43]) focuses on natural language understanding, requiring the model to infer the logical relationship between pairs of sentences.

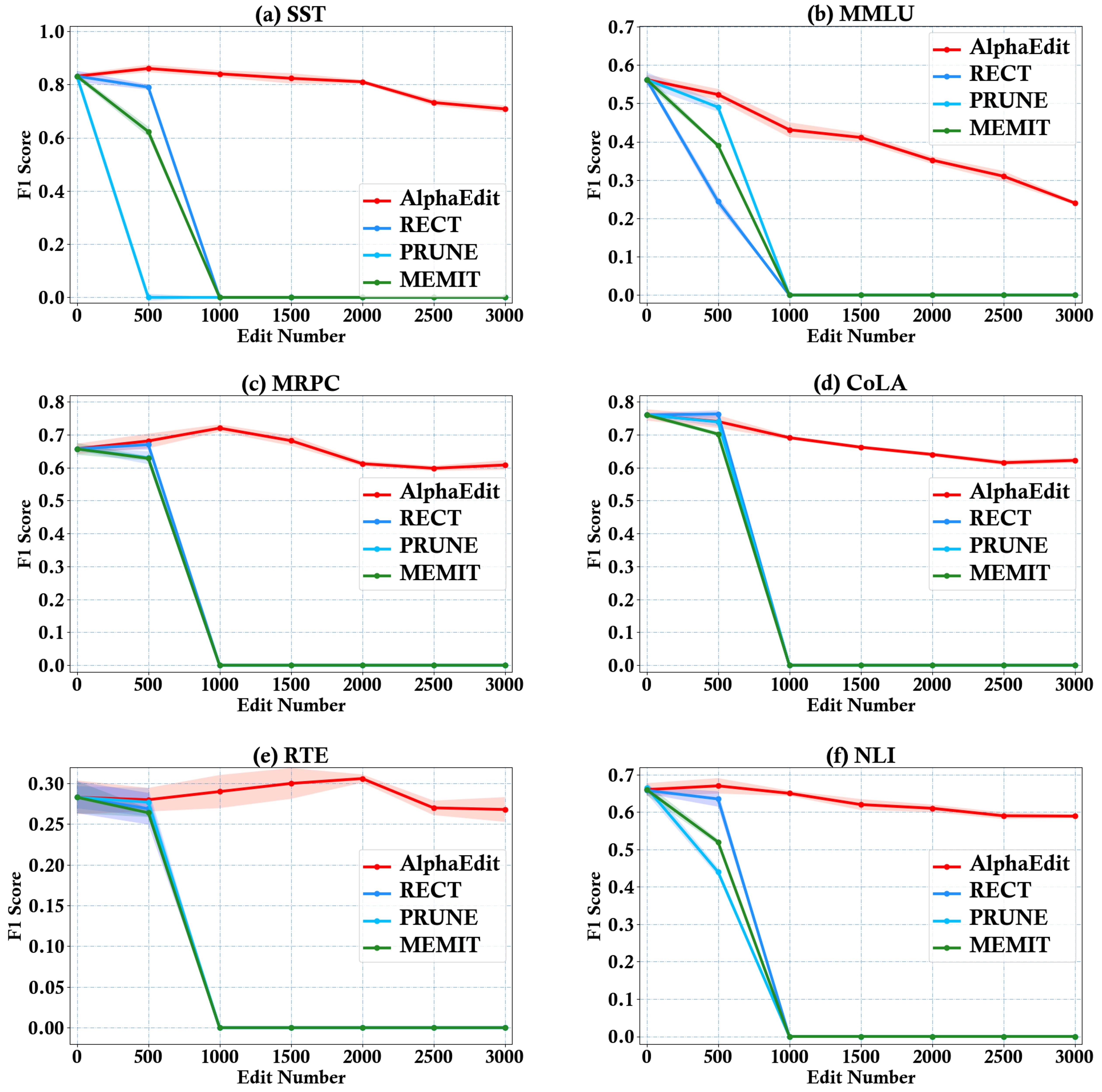

Figure 4 illustrates the performance as the number of edited samples increases across six tasks. More results are provided in Appendix C.2. Based on Figure 4, we have the following observations:

- Obs 3: AlphaEdit sustains the general capability of post-edited LLMs even after extensive editing. Specifically, AlphaEdit maintains the original model performance across all metrics, even after editing 3, 000 samples,

demonstrating that the null-space projection not only safeguards the preserved knowledge but also protects the general capability learned from this knowledge's corpus.

- Obs 4: LLMs edited with baseline methods experience significant degradation of general capability after editing 2, 000 samples. Specifically, in this case, all metrics are rapidly approaching zero, confirming our theoretical analysis that the common objective are inherently flawed and fail to balance knowledge update and preservation.

4.4 Hidden Representations Analysis (RQ3)

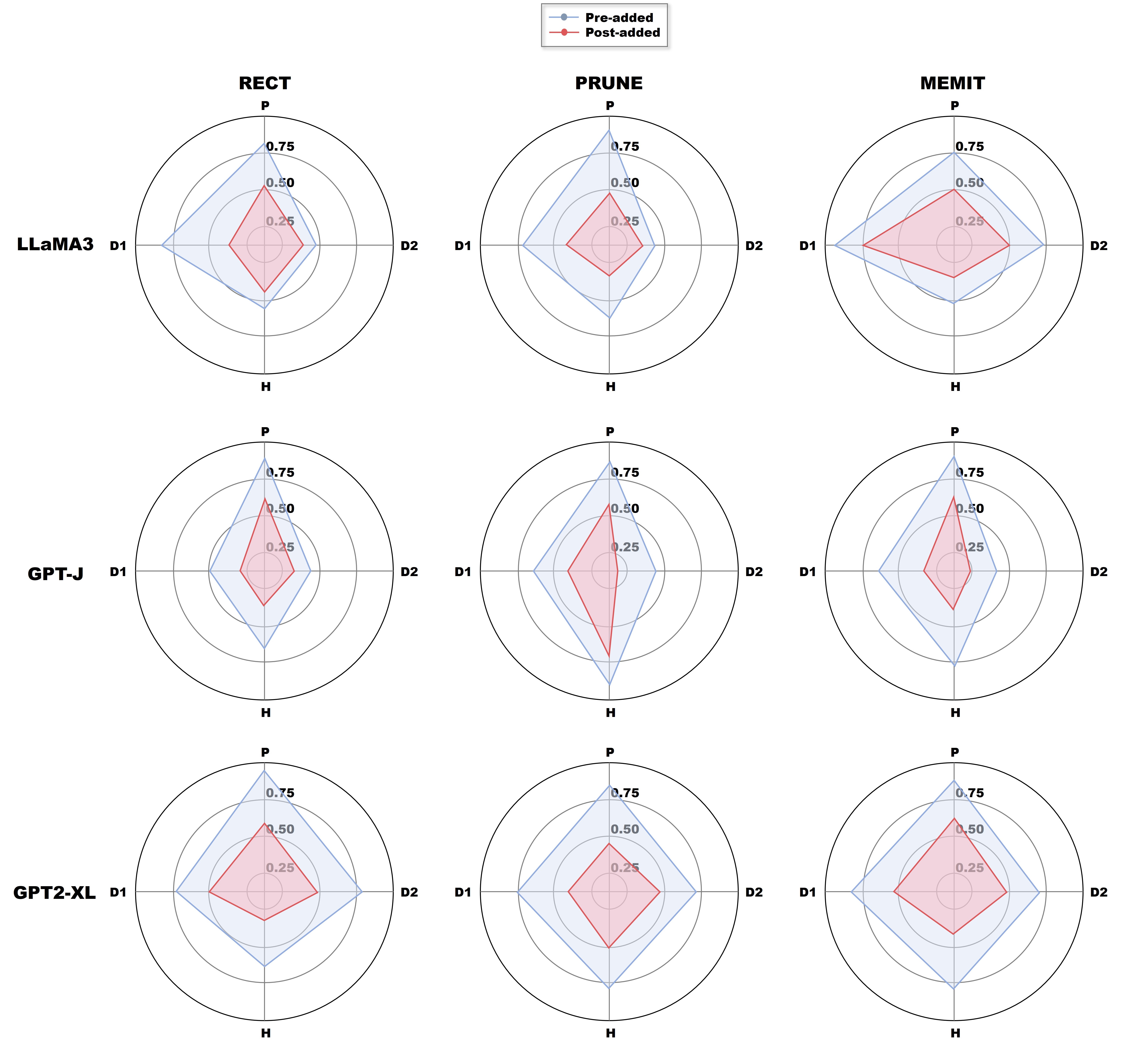

As discussed in previous sections, current editing methods often cause post-edited LLMs to overfit to the updated knowledge, leading to a shift in the distribution of hidden representations. Hence, here we aim to empirically verify that AlphaEdit can prevent overfitting and avoid this distributional shift. To validate it, we conducted the following steps: (1) We randomly select 1, 000 factual prompts and extract the hidden representations within pre-edited LLMs. (2) Subsequently, we performed 2, 000 sequential edits on the LLMs and recomputed these hidden representation. (3) Finally, we used t-SNE ([44]) to visualize the hidden representation before and after editing. Figure 5 exhibits them and their marginal distribution curves. Furthermore, we quantify the deviation of scatter point distributions and the differences of marginal distribution curves in Figure 5, and the results are provided in Appendix C.3. According to Figure 5 we can find that:

- Obs 5: AlphaEdit maintains consistency in hidden representations after editing. Specifically, the hidden representations within LLMs edited using AlphaEdit remain consistent with the original distribution across all three base models. This stability indicates that AlphaEdit effectively mitigates overfitting, in turn explaining its superior knowledge preservation and generalization capabilities.

- Obs 6: There is a significant shift in the distribution of hidden representations within baseline-edited LLMs. In some cases (*e.g., * RECT-edited LLaMA3), the trend of the distribution before and after editing is even completely reversed. This discrepancy becomes more pronounced as sequential editing progresses, further underscoring the importance of projection-based optimization.

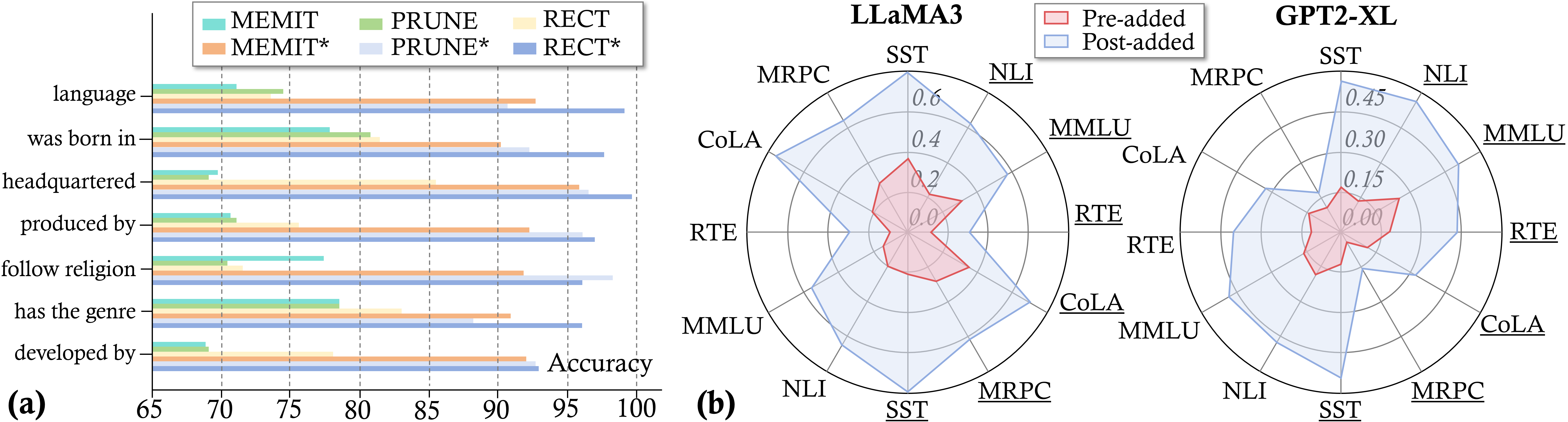

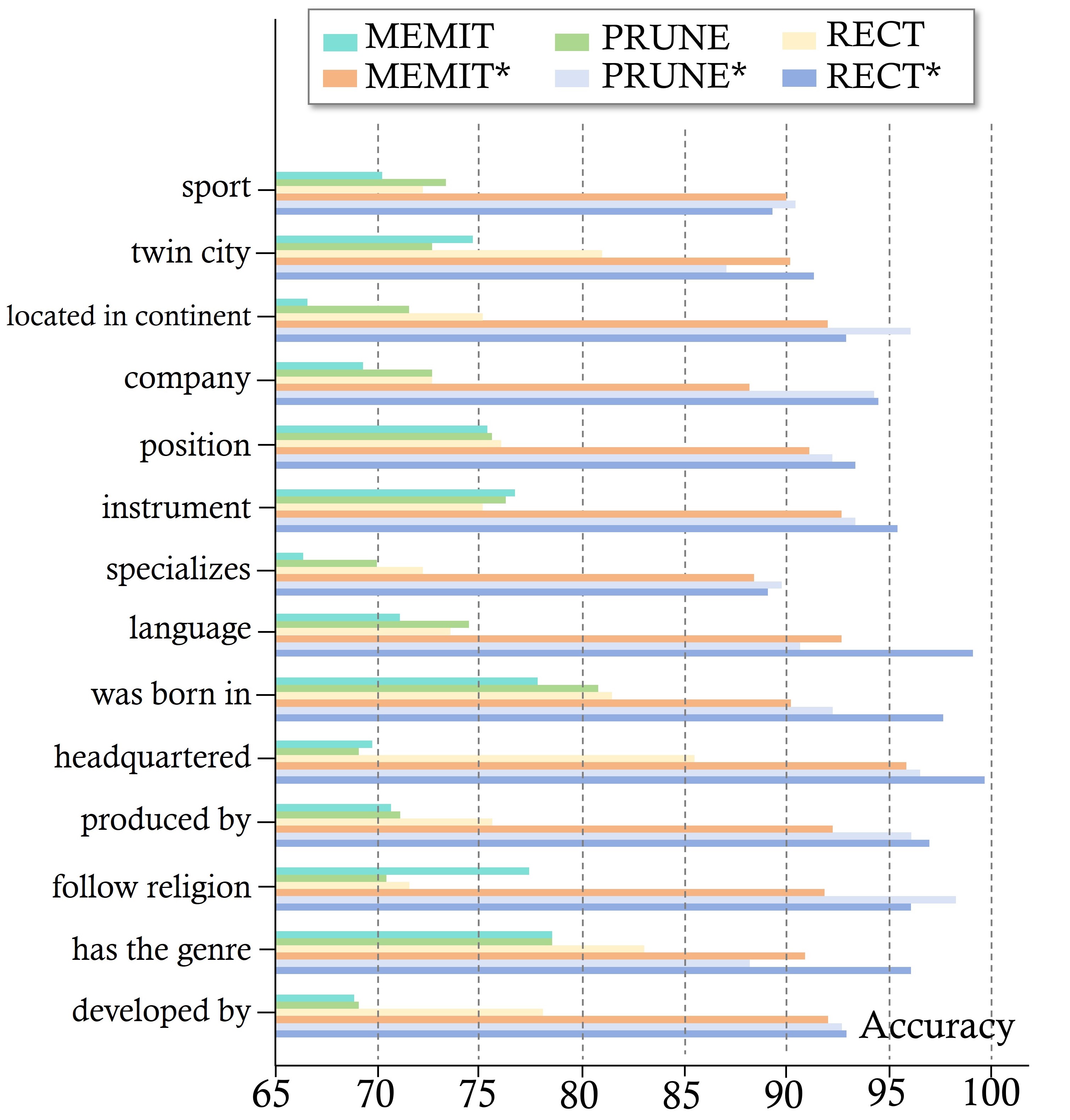

4.5 Performance Improvements of Baseline Methods (RQ4)

We conclude by evaluating whether integrating AlphaEdit's projection strategy can comprehensively enhance current editing methods. To achieve this, we add one line of code from AlphaEdit (the code for projection) to baselines and measure their performance before and after the addition. Following previous works ([10]), we analyze (1) the average performance across all editing samples, (2) the performance on editing samples involving specific semantics and (3) the general capability of post-edited LLMs. Results are shown in Figure 6, Figure 7 (a), and Figure 7 (b), respectively. Note that in Figure 7 (a), the y-axis represents the knowledge belonging to different semantic categories. For instance, the labeled "language" indicates the knowledge instances related to language. Detailed experimental settings can be found in Appendix C.4. The results show that:

- Obs 7: AlphaEdit seamlessly integrates with other model editing methods, significantly boosting their overall performance. The optimized baselines show an average improvement of 28.24%28.24\%28.24% on editing capability and 42.65%42.65\%42.65% on general capability, underscoring the substantial potential and broad applicability of the null-space projection in enhancing model editing methods.

5. Related Work

In this section, model editing methods are categorized into two main approaches: parameter-modifying and parameter-preserving techniques. Parameter-modifying methods either use meta-learning strategies, where hypernetworks like KE, MEND, and InstructEdit adapt model parameters for multi-task editing, or locate-then-edit approaches like ROME and MEMIT that identify and directly modify feed-forward module weights storing factual knowledge, with extensions like GLAME leveraging knowledge graphs and AnyEdit enabling recursive editing of arbitrary-length knowledge. Parameter-preserving methods instead use auxiliary modules—codebooks, neurons, or external models as in SERAC, T-Patcher, GRACE, and MELO—or incorporate knowledge into prompts like MemPrompt and IKE, with WISE recently introducing dual memory and conflict-free sharding to balance reliability and generalization. These developments are evaluated using diverse benchmarks including KnowEdit for knowledge insertion and modification, and LEME, CKnowEdit, and MQuAKE for long-form, multi-lingual, and multi-hop knowledge assessments, collectively enabling comprehensive evaluation of editing efficacy.

Parameter-modifying Model Editing. This approach typically employs meta-learning or locating-then-editing strategies ([36]) to conduct editing. Meta-learning, as implemented by KE ([5]) and MEND ([6]), involves adapting model parameters through a hypernetwork. InstructEdit ([30]) extends MEND by designing instructions for training on different tasks. Locate-then-edit strategies, exemplified by ROME ([16]) and MEMIT ([10]), prioritize pinpointing the knowledge's storage location before making targeted edits. GLAME ([45]) enhances ROME by leveraging knowledge graphs to facilitate the editing of related knowledge. Recent work has introduced AnyEdit ([11]), a recursive approach designed to modify knowledge of arbitrary length and format stored within LLMs.

Parameter-preserving Model Editing. This line utilizes additional modules to store to-be-updated knowledge. These modules may include codebooks, neurons, or auxiliary models, as seen in methods like SERAC ([7]), T-Patcher ([12]), GRACE ([14]), and MELO ([13]). Additionally, MemPrompt ([46]) and IKE ([15]) achieve editing by incorporating to-be-updated knowledge into input prompts. More recently, WISE ([47]) innovates prior module designs by introducing dual memory and conflict-free knowledge sharding, overcoming trade-off between reliability and generalization.

Evaluating Knowledge Editing. Recent work has introduced diverse benchmarks to assess the efficacy of model editing. For instance, KnowEdit ([36]) provides a unified datasets by collecting different types of knowledge tailored for knowledge insertion, modification, and erasure tasks; LEME ([34]), CKnowEdit ([48]), and MQuAKE ([35]) shift attention to long-form, multi-lingual, and multi-hop knowledge, respectively. These benchmarks collectively push for more comprehensive evaluations.

6. Limitations & Future Discussion

While AlphaEdit demonstrates the capability to edit knowledge with minimal performance degradation, we also recognize its limitations. Concretely, its applicability to multi-modal LLMs ([49]) and large reasoning models ([4]) remains unexplored. Hence, future research could focus on extending AlphaEdit to a broader range of base LLMs. Furthermore, the superior performance of null-space projection in balancing knowledge updates and preservation suggests its potential for broader applications. Especially, it could enhance specific LLM capabilities — such as safety, mathematics, or biochemistry — without degrading other abilities. These avenues present exciting opportunities to improve both the applicability and scalability of our method.

7. Conclusion

In this section, the authors conclude their presentation of AlphaEdit, a novel model editing method designed to resolve the fundamental trade-off between updating knowledge in large language models and preserving their existing capabilities. The method achieves this balance through a remarkably simple intervention: projecting parameter perturbations onto the null space of key matrices, which ensures that updates affect only the target knowledge while leaving preserved knowledge undisturbed. This null-space projection requires only a single line of code to implement, making it both elegant and practical. Extensive experimental validation across multiple base models—including LLaMA3, GPT-2 XL, and GPT-J—demonstrates that AlphaEdit substantially outperforms existing editing approaches, achieving an average improvement of 36.7% in editing capabilities. The results confirm that AlphaEdit not only addresses a critical limitation in current model editing techniques but does so with minimal computational overhead and maximal effectiveness.

In this work, we introduced AlphaEdit, a novel model editing method to address a critical challenge in current approaches — the trade-off between knowledge update and preservation — with only a single line of code. Specifically, AlphaEdit minimizes disruption to the preserved knowledge by projecting parameter perturbations onto the null space of its key matrices, allowing the model to focus solely on knowledge update. Extensive experiments on multiple base LLMs, including LLaMA3, GPT-2 XL, and GPT-J, demonstrate that AlphaEdit significantly enhances the performance of existing model editing methods, delivering an average improvement of 36.7%36.7\%36.7% in editing capabilities.

Ethics Statement

In this section, the authors acknowledge that while AlphaEdit significantly enhances sequential model editing performance and provides valuable capabilities for updating and managing knowledge in large language models, the technology introduces potential ethical risks. The ability to directly modify stored knowledge could enable the introduction of false or harmful information into models, creating serious concerns about misuse. To mitigate these risks, the authors strongly urge researchers to implement strict validation and oversight mechanisms when applying these editing techniques. Despite these concerns, they emphasize that the fundamental purpose of model editing remains positive—to enable efficient updates of large models as knowledge evolves. The authors conclude by encouraging the research community to leverage this technology responsibly and with appropriate care, balancing innovation with ethical considerations to ensure that advancements in model editing serve beneficial purposes while minimizing potential harms.

Our AlphaEdit method significantly enhances the performance of sequential model editing, making it invaluable for updating and managing knowledge in real-world applications. While the ability to directly modify stored knowledge introduces potential risks, such as the introduction of false or harmful information, we strongly urge researchers to implement strict validation and oversight to ensure the ethical use of these techniques. Nevertheless, the original goal of model editing is positive, aiming to facilitate efficient updates of large models in the future. Therefore, we encourage researchers to leverage this technology responsibly and with care.

Reproducibility

In this section, the authors address reproducibility by providing comprehensive resources for researchers to verify and replicate their AlphaEdit method. Detailed implementation instructions are available in Appendix A, covering experimental configurations, datasets, metrics, and hyperparameter settings for different base models including GPT-2 XL, GPT-J, and LLaMA3. The source code is publicly accessible through a GitHub repository, ensuring transparency and ease of access for the research community. These measures collectively enable other researchers to independently validate the reported findings, replicate the experiments across multiple large language models and benchmarks, and build upon the work. By making both detailed documentation and code openly available, the authors facilitate rigorous scientific verification and encourage further development of projection-based model editing techniques in the field.

To ensure the reproducibility of our findings, detailed implementation instructions for AlphaEdit can be found in Appendix A. Additionally, the source code is publicly available at the following URL:

https://github.com/jianghoucheng/AlphaEdit. These measures are intended to facilitate the verification and replication of our results by other researchers in the field.

Acknowledgement

In this section, the authors acknowledge the funding sources and external support that enabled their research on AlphaEdit. The work received financial backing from three grants provided by the National Science and Technology Major Project and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, specifically projects numbered 2023ZD0121102, 92270114, and U24B20180. Beyond monetary support, the research benefited from technical assistance provided by the EasyEdit platform, an open-source framework for model editing available on GitHub. This acknowledgement highlights the collaborative nature of advanced AI research, where institutional funding from Chinese national science programs and community-driven open-source tools combine to facilitate innovations in large language model editing. The authors express gratitude for these resources, which were instrumental in developing and validating their novel null-space projection method for balancing knowledge updates with preservation of existing model capabilities.

This research is supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD0121102), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92270114), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24B20180). We also thank the EasyEdit platform for their support (

https://github.com/zjunlp/EasyEdit).

Appendix

A. Experimental Setup

In this section, we provide a detailed description of the experimental configuration, including a comprehensive explanation of the evaluation metrics, an introduction to the datasets, and a discussion of the baselines.

A.1 Datasets

Here, we provide a detailed introduction to the datasets used in this paper:

- Counterfact ([16]) is a more challenging dataset that contrasts counterfactual with factual statements, initially scoring lower for Counterfact. It constructs out-of-scope data by replacing the subject entity with approximate entities sharing the same predicate. The Counterfact dataset has similar metrics to ZsRE for evaluating efficacy, generalization, and specificity. Additionally, Counterfact includes multiple generation prompts with the same meaning as the original prompt to test the quality of generated text, specifically focusing on fluency and consistency.

- ZsRE ([33]) is a question answering (QA) dataset that uses questions generated through back-translation as equivalent neighbors. Following previous work, natural questions are used as out-of-scope data to evaluate locality. Each sample in ZsRE includes a subject string and answers as the editing targets to assess editing success, along with the rephrased question for generalization evaluation and the locality question for evaluating specificity.

- KnowEdit ([36]) introduces a comprehensive benchmark aimed at systematically evaluating knowledge editing methods, categorizing them into approaches that rely on external knowledge, intrinsic knowledge updates, or merging new knowledge into the model. The benchmark not only measures the impact of editing on specific domains but also emphasizes preserving the model’s overall performance across tasks, offering a unified framework for evaluating editing efficiency and impact. In our paper, we employ the wiki_recent and wikibio within KnowEdit to conduct our experiments.

- LEME (Long-form Evaluation of Model Editing) ([34]) extends the evaluation paradigm by focusing on long-form generative outputs, revealing unique challenges such as factual drift, internal consistency, and lexical cohesion. This protocol highlights that short-form metrics fail to correlate with long-form generative outcomes, shedding light on previously unexplored dimensions of editing.

- MQuAKE ([35]) addresses a critical gap in current evaluations by introducing multi-hop reasoning questions to test the ripple effects of factual updates. Unlike single-fact recall benchmarks, MQUAKE measures the consistency of entailed beliefs after editing, uncovering limitations in existing methods when handling complex relational dependencies.

A.2 Metrics

Now we introduce the evaluation metrics used for ZsRE and Counterfact datasets, respectively.

A.2.1 ZsRE Metrics

Following the previous work ([6, 16, 10]), this section defines each ZsRE metric given a LLM fθf_\thetafθ, a knowledge fact prompt (si,ri)(s_i, r_i)(si,ri), an edited target output oio_ioi, and the model's original output oico_i^coic:

- Efficacy: Efficacy is calculated as the average top-1 accuracy on the edit samples:

- Generalization: Generalization measures the model's performance on equivalent prompt of (si,ri)(s_i, r_i)(si,ri), such as rephrased statements N((si,ri))N((s_i, r_i))N((si,ri)). This is evaluated by the average top-1 accuracy on these N((si,ri))N((s_i, r_i))N((si,ri)):

- Specificity: Specificity ensures that the editing does not affect samples unrelated to the edit cases O(si,ri)O(s_i, r_i)O(si,ri). This is evaluated by the top-1 accuracy of predictions that remain unchanged:

A.2.2 Counterfact Metrics

Following previous work ([16, 10]), this section defines each Counterfact metric given a LLM fθf_\thetafθ, a knowledge fact prompt (si,ri)(s_i, r_i)(si,ri), an edited target output oio_ioi, and the model's original output oico_i^coic:

- Efficacy (efficacy success): The proportion of cases where oio_ioi is more probable than ocio_c^ioci with the (si,ri)(s_i, r_i)(si,ri) prompt:

- Generalization (paraphrase success): The proportion of cases where oio_ioi is more probable than ocio_c^ioci in rephrased statements N((si,ri))N((s_i, r_i))N((si,ri)):

- Specificity (neighborhood success): The proportion of neighborhood prompts O((si,ri))O((s_i, r_i))O((si,ri)), which are prompts about distinct but semantically related subjects, where the model assigns a higher probability to the correct fact:

- Fluency (generation entropy): Measure for excessive repetition in model outputs. It uses the entropy of n-gram distributions:

where gn(⋅)g_n(\cdot)gn(⋅) is the n-gram frequency distribution.

- Consistency (reference score): The consistency of the model's outputs is evaluated by giving the model fθ{f_\theta}fθ a subject sss and computing the cosine similarity between the TF-IDF vectors of the model-generated text and a reference Wikipedia text about ooo.

A.3 Implementation Details

Our implementation of AlphaEdit with GPT-2 XL and GPT-J follows the configurations outlined in MEMIT ([10]). Specifically,

- For the GPT-2 XL model, we target critical layers [13,14,15,16,17][13, 14, 15, 16, 17][13,14,15,16,17] for editing, with the hyperparameter λ\lambdaλ set to 20, 000. During the computation of hidden representations of the critical layer, we perform 20 optimization steps with a learning rate of 0.5.

- For the GPT-J model, we target critical layers [3,4,5,6,7,8][3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8][3,4,5,6,7,8] for editing, with the hyperparameter λ\lambdaλ set to 15, 000. During the computation of hidden representations of the critical layer, we perform 25 optimization steps, also with a learning rate of 0.5.

- For Llama3 (8B) model, we target critical layers [4,5,6,7,8][4, 5, 6, 7, 8][4,5,6,7,8] for editing. The hyperparameter λ\lambdaλ is set to 15, 000. During the process of computing hidden representations of the critical layer, we perform 25 steps with a learning rate of 0.1.

All experiments are conducted on a single A40 (48GB) GPU. The LLMs are loaded using HuggingFace Transformers ([50]).

A.4 Baselines

Here we introduce the five baseline models employed in this study. For the hyperparameter settings of the baseline methods, except the settings mentioned in Appendix A.3, we used the original code provided in the respective papers for reproduction. It is important to note that, since the code for PRUNE is not publicly available, we implemented the method based on the description in the original paper. Specifically, in our implementation, the threshold for retaining eigenvalues in PRUNE was set to eee.

- MEND is a method for efficiently editing large pre-trained models using a single input-output pair. MEND utilizes small auxiliary networks to make fast, localized changes to the model without full retraining. By applying a low-rank decomposition to the gradient from standard fine-tuning, MEND enables efficient and tractable parameter adjustments. This approach allows for post-hoc edits in large models while avoiding the overfitting common in traditional fine-tuning methods.

- InstructEdit enables the learning of a well-formed Editor by designing corresponding instructions for training on different tasks. InstructEdit applies meta-learning editing methods based on MEND to train the editor with a variety of meticulously curated instructions, and through this approach, InstructEdit can endow the Editor with the capacity for multi-task editing, thus saving a significant amount of human and computational resources.

- ROME is a method for updating specific factual associations in LLMs. By identifying key neuron activations in middle-layer feed-forward modules that influence factual predictions, ROME modifies feed-forward weights to edit these associations directly. ROME demonstrates that mid-layer feed-forward modules play a crucial role in storing and recalling factual knowledge, making direct model manipulation a viable editing technique.

- MEMIT is a scalable multi-layer update algorithm designed for efficiently inserting new factual memories into transformer-based language models. Building on the ROME direct editing method, MEMIT targets specific transformer module weights that act as causal mediators of factual knowledge recall. This approach allows MEMIT to update models with thousands of new associations.

- PRUNE is a model editing framework designed to preserve the general abilities of LLMs during sequential editing. PRUNE addresses the issue of deteriorating model performance as the number of edits increases by applying condition number restraints to the edited matrix, limiting perturbations to the model's stored knowledge. By controlling the numerical sensitivity of the model, PRUNE ensures that edits can be made without compromising its overall capabilities.

- RECT is a method designed to mitigate the unintended side effects of model editing on the general abilities of LLMs. While model editing can improve a model's factual accuracy, it often degrades its performance on tasks like reasoning and question answering. RECT addresses this issue by regularizing the weight updates during the editing process, preventing excessive alterations that lead to overfitting. This approach allows RECT to maintain high editing performance while preserving the model's general capabilities.

- SERAC ([7]) introduces Semi-Parametric Editing with a Retrieval-Augmented Counterfactual Model, addressing limitations of traditional editors in defining edit scope and handling sequential updates. It stores edits in explicit memory and reasons over them to adjust model behavior as needed. SERAC outperforms existing methods on three challenging tasks—question answering, fact-checking, and dialogue generation.

- MELO ([13]) proposes Neuron-Indexed Dynamic LoRA, a plug-in method that dynamically activates LoRA blocks to edit model behavior efficiently. Adaptable across multiple LLM backbones, it achieves state-of-the-art performance on tasks like document classification, question answering, and hallucination correction, with minimal computational cost and trainable parameters.

- GRACE ([14]) introduces a lifelong model editing framework that uses a local codebook in the latent space to handle thousands of sequential edits without degrading model performance. It makes targeted fixes while preserving generalization, demonstrating superior results on T5, BERT, and GPT for retaining and generalizing edits.

B. Implementation Details of Current Model Editing & Related Proofs

Here, we provide the implementation details of the current model editing methods along with the proof process related to it and the concept of the null space ([20]).

B.1 Model Editing

Model editing aims to refine a pre-trained model through one or multiple edits, while each edit replaces (s,r,o)(s, r, o)(s,r,o) with the new knowledge (s,r,o∗)(s, r, o^\ast)(s,r,o∗) ([51, 52]). Then, model is expected to recall the updated object o∗o^\asto∗ given a natural language prompt p(s,r)p(s, r)p(s,r), such as "The President of the United States is" ([53]).

To achieve this, locating-and-editing methods are proposed for effectively model editing ([54, 55]). These methods typically adhere to the following steps ([56]):

Step 1: Locating Influential Layers. The first step is to identify the specific FFN layers to edit using causal tracing ([16]). This method involves injecting Gaussian noise into the hidden states, and then incrementally restoring them to original values. By analyzing the degree to which the original output recovers, the influential layers can be pinpointed as the targets for editing.

Step 2: Acquiring the Excepted Output. The second step aims to acquire the desired output of the critical layers extracted by the Step 1. Concretely, following the aforementioned key-value theory, the key k {\bm{k}}k, which encodes (s,r)(s, r)(s,r), is processed through the output weights Woutl {\bm{W}}_{\text{out}}^lWoutl to produce the original value v {\bm{v}}v encoding ooo. Formally:

To achieve knowledge editing, v {\bm{v}}v is expected to be replaced with a new value v∗ {\bm{v}}^\astv∗ encoding o∗o^\asto∗. To this end, current methods typically use gradient descent on v {\bm{v}}v, maximizing the probability that the model outputs the word associated with o∗o^\asto∗ ([10]). The optimization objective is as follows:

where fWoutl(ml+=δ)f_{{\bm{W}}_{\text{out}}^l}({\bm{m}}^l += {\mathbf{\boldsymbol{\delta}}})fWoutl(ml+=δ) represents the original model with ml {\bm{m}}^lml updated to ml+δl {\bm{m}}^l + \mathbf{\boldsymbol{\delta}}^lml+δl.

Step 3: Updating Woutl {\bm{W}}_{\text{out}}^lWoutl. This step aims to update the parameters Woutl{{{\bm{W}}}_{\text{out}}^l}Woutl. It includes a factual set {K1,V1}\{{\bm{K}}_1, {\bm{V}}_1\}{K1,V1} containing uuu new associations, while preserving the set {K0,V0}\{{\bm{K}}_0, {\bm{V}}_0\}{K0,V0} containing nnn original associations. Specifically,

where vectors k {\bm{k}}k and v {\bm{v}}v defined in Eqn. 10 and their subscripts represent the index of the knowledge. Based on these, the objective can be defined as:

By applying the normal equation ([28]), its closed-form solution can be derived:

Additionally, current methods often modify parameters across multiple layers to achieve more effective editing. For more details, please refer to [10].

B.2 Proof for the Shared Null Space of K0K_0K0 and K0(K0)TK_0 (K_0)^TK0(K0)T

Theorem: Let K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 be a m×nm \times nm×n matrix. Then K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 and K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T share the same left null space.

Proof: Define the left null space of a matrix A {\bm{A}}A as the set of all vectors x\mathbf{x}x such that xTA=0\mathbf{x}^T {\bm{A}} = 0xTA=0. We need to show that if x\mathbf{x}x is in the left null space of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0, then x\mathbf{x}x is also in the left null space of K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T, and vice versa.

- Inclusion N(xTK0)⊆N(xTK0(K0)T)\mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{x}^T K_0\right) \subseteq \mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{x}^T K_0\left(K_0\right)^T\right)N(xTK0)⊆N(xTK0(K0)T):

- Suppose x\mathbf{x}x is in the left null space of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0, i.e., xTK0=0\mathbf{x}^T {\bm{K}}_0 = \bm{0}xTK0=0.

- It follows that xT(K0(K0)T)=(xTK0)(K0)T=0⋅(K0)T=0\mathbf{x}^T\left(K_0\left(K_0\right)^T\right)=\left(\mathbf{x}^T K_0\right)\left(K_0\right)^T=\bm{0} \cdot\left(K_0\right)^T=\bm{0}xT(K0(K0)T)=(xTK0)(K0)T=0⋅(K0)T=0.

- Therefore, x\mathbf{x}x is in the left null space of K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T.

- Inclusion N(xTK0(K0)T)⊆N(xTK0)\mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{x}^T K_0\left(K_0\right)^T\right) \subseteq \mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{x}^T K_0\right)N(xTK0(K0)T)⊆N(xTK0):

- Suppose x\mathbf{x}x is in the left null space of K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T, i.e., xT(K0(K0)T)=0\mathbf{x}^T\left(K_0\left(K_0\right)^T\right)=\bm{0}xT(K0(K0)T)=0.

- Expanding this expression gives (xTK0)(K0)T=0\left(\mathbf{x}^T K_0\right)\left(K_0\right)^T=\bm{0}(xTK0)(K0)T=0.

- Since K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T is non-negative (as any vector multiplied by its transpose results in a non-negative scalar), xTK0\mathbf{x}^T {\bm{K}}_0xTK0 must be a zero vector for their product to be zero.

- Hence, x\mathbf{x}x is also in the left null space of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0.

From these arguments, we establish that both K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 and K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T share the same left null space. That is, x\mathbf{x}x belongs to the left null space of K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 if and only if x\mathbf{x}x belongs to the left null space of K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T. This equality of left null spaces illustrates the structural symmetry and dependency between K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 and its self-product K0(K0)T {\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T.

B.3 Proof for Equation ΔPK0(K0)T=0\Delta P K_0 (K_0)^T=0ΔPK0(K0)T=0

The SVD of K0(K0)T{\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T provides us the eigenvectors U{\bm{U}}U and eigenvalues Λ{\bm{\Lambda}}Λ. Based on this, we can express U{\bm{U}}U and Λ{\bm{\Lambda}}Λ as U=[U1,U2]{\bm{U}} = [{\bm{U}}_1, {\bm{U}}_2]U=[U1,U2] and correspondingly $ {\bm{\Lambda}} =

,whereallzeroeigenvaluesarecontainedin, where all zero eigenvalues are contained in ,whereallzeroeigenvaluesarecontainedin {\bm{\Lambda}}_2 ,and, and ,and {\bm{U}}_2 consistsoftheeigenvectorscorrespondingtoconsists of the eigenvectors corresponding toconsistsoftheeigenvectorscorrespondingto {\bm{\Lambda}}_2 $.

Since U{\bm{U}}U is an orthogonal matrix, it follows that:

This implies that the column space of U2{\bm{U}}_2U2 spans the null space of K0(K0)T{\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T. Accordingly, the projection matrix onto the null space of K0(K0)T{\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T can be defined as:

Based on the Eqn. 14 and 15, we can derive that:

which confirms that ΔP\Delta {\bm{P}}ΔP projects Δ\DeltaΔ onto the null space of K0(K0)T{\bm{K}}_0 ({\bm{K}}_0)^TK0(K0)T.

B.4 Derivation of AlphaEdit Perturbation

Given the orthogonal projection matrix P=U^U^⊤ {\bm{P}} = \hat{{\bm{U}}}\hat{{\bm{U}}}^\topP=U^U^⊤ with U^⊤U^=I\hat{{\bm{U}}}^\top\hat{{\bm{U}}} = {\bm{I}}U^⊤U^=I, it satisfies P=P⊤ {\bm{P}} = {\bm{P}}^\topP=P⊤ and P2=P {\bm{P}}^2 = {\bm{P}}P2=P. We aim to minimize the objective:

where R=V1−WK1 {\bm{R}} = {\bm{V}}_1 - {\bm{W}} {\bm{K}}_1R=V1−WK1. Setting the matrix derivative ∂J∂Δ~\frac{\partial J}{\partial \bm{\tilde{\Delta}}}∂Δ~∂J to zero yields:

Simplifying via Projection Properties: Factorize ΔP\bm{\Delta} {\bm{P}}ΔP and utilize P=P⊤ {\bm{P}} = {\bm{P}}^\topP=P⊤, P2=P {\bm{P}}^2 = {\bm{P}}P2=P:

Closed-Form Solution: Left-multiplying by the inverse of the bracketed term gives:

where the solution is constrained to the column space of U^\hat{{\bm{U}}}U^ via P {\bm{P}}P.

B.5 Invertibility of (KpKpTP+K1K1TP+αI)(K_p K_p^T P + K_1 K_1^T P +\alpha I)(KpKpTP+K1K1TP+αI)

To prove the invertibility of the matrix (KpKpTP+K1K1TP+αI)({\bm{K}}_p {\bm{K}}_p^T {\bm{P}} + {\bm{K}}_1 {\bm{K}}_1^T {\bm{P}} + \alpha {\bm{I}})(KpKpTP+K1K1TP+αI), note that KpKpT{\bm{K}}_p {\bm{K}}_p^TKpKpT and K1K1T{\bm{K}}_1 {\bm{K}}_1^TK1K1T are symmetric and positive semidefinite matrices, and P{\bm{P}}P is a projection matrix which is also symmetric and positive semidefinite. Since P{\bm{P}}P projects onto a subspace, the matrices KpKpTP{\bm{K}}_p {\bm{K}}_p^T {\bm{P}}KpKpTP and K1K1TP{\bm{K}}_1 {\bm{K}}_1^T {\bm{P}}K1K1TP are positive semidefinite.

Adding the term αI\alpha {\bm{I}}αI, where α>0\alpha > 0α>0, to these positive semidefinite matrices makes the entire matrix positive definite. This is because the addition of αI\alpha {\bm{I}}αI increases each eigenvalue by α\alphaα, ensuring that all eigenvalues are positive, thereby making the matrix invertible. Thus, the matrix (KpKpTP+K1K1TP+αI {\bm{K}}_p {\bm{K}}_p^T {\bm{P}} + {\bm{K}}_1 {\bm{K}}_1^T {\bm{P}} + \alpha {\bm{I}}KpKpTP+K1K1TP+αI) is invertible.

C. More Experimental Results

C.1 Case Study

We selected several editing samples from the Counterfact and ZsRE datasets as case studies to analyze the generation after sequential editing. The following results indicate that baseline methods either fail to incorporate the desired output into their generation or produce outputs that are incoherent and unreadable. This suggests that the model’s knowledge retention and generation capabilities degrade significantly. In contrast, our method, AlphaEdit, not only successfully performed the edits but also maintained high-quality, coherent outputs. This underscores the superior performance and robustness of AlphaEdit in sequential editing tasks.

C.1.1 Case 1

C.2 General Capability Tests

Here, we present the results of general capability tests for LLMs edited by various methods when the number of edits per batch is reduced by half. The results are shown in Figure 8. Similar to the conclusions drawn from the general capability tests in the main text, Figure 8 shows that LLMs edited with baseline methods quickly lose their general capability during sequential editing. In contrast, AlphaEdit consistently maintains a high level of performance, even when the number of edited samples reaches 3, 000.

C.3 Quantification of Distribution Shift

Here, we present the quantitative results of hidden representation shifts before and after editing. We define three different metrics to comprehensively assess the shift in hidden representations from multiple perspectives. Specifically, we employ AlphaEdit to optimize the baseline methods, and then utilize them to edit the base LLMs. The results are shown in Figure 9.

In more detail, in Figure 9, we first calculate the overlap between the marginal distribution curves before and after editing, with the overlap across two dimensions defined as metrics D1D1D1 and D2D2D2. Next, we introduced the Hausdorff distance, labeled as HHH, to measure the distance between the edited and original distributions. Finally, we calculated the probability that post-edit data points in the confidence interval of the pre-edit distribution, defining this metric as PPP.

Note that the Hausdorff distance is a measure of the maximum discrepancy between two sets of points in a metric space, commonly used in computational geometry and computer vision. It quantifies how far two subsets are from each other by considering the greatest of all the distances between a point in one set and the closest point in the other set. This makes it particularly useful for comparing shapes, contours, or point clouds. For two sets AAA and BBB in a metric space, the Hausdorff distance dH(A,B)=max{supa∈Ainfb∈Bd(a,b),supb∈Binfa∈Ad(b,a)}d_H(A, B)=\max \left\{\sup _{a \in A} \inf _{b \in B} d(a, b), \sup _{b \in B} \inf _{a \in A} d(b, a)\right\}dH(A,B)=max{supa∈Ainfb∈Bd(a,b),supb∈Binfa∈Ad(b,a)} is defined as:

where:

- d(a,b)d(a, b)d(a,b) is the distance between points aaa and bbb (often the Euclidean distance);

- infb∈Bd(a,b)\inf _{b \in B} d(a, b)infb∈Bd(a,b) represents the distance from point aaa in set AAA to the nearest point in set BBB;

- supa∈A\sup _{a \in A}supa∈A is the supremum (*i.e., * maximum) of all such minimum distances from AAA to BBB, and similarly for points in BBB to AAA.

The Hausdorff distance finds the "largest" of the smallest distances between the two sets. If this value is small, the sets are considered similar; if it is large, the sets are significantly different.

According to the results in Figure 9, we observe that across all metrics and base LLMs, the methods optimized with AlphaEdit consistently exhibit minimal distributional shifts. This further supports the qualitative analysis presented in the main text, demonstrating that AlphaEdit effectively prevents post-edited LLMs from overfitting hidden representations to the updated knowledge, thereby preserving the original knowledge.

C.4 Editing Facts involving Various Semantics

To gain a deeper understanding of the performance when editing facts involving different semantics, following MEMIT ([10]), we selected several semantics from the Counterfact dataset, each containing at least 300 examples, and evaluated the performance of each baseline methods on these examples (which were evenly distributed across the sequential editing batches). Some of the results are shown in Figure 7 in the main text, with more comprehensive results displayed in Figure 10. In these figures, the horizontal axis represents Accuracy, defined as the average of Efficacy and Generalization across the 300 examples. For instance, the bar labeled "language, " with a height of 98, indicates that out of 1, 000 knowledge instances related to language (e.g., "The primary language in the United States is English, " or "The official language of France is French"), AlphaEdit successfully edited 98% of them. This metric provides a fine-grained assessment of AlphaEdit's effectiveness across various knowledge domains. The results in Figure 10 show that methods incorporating the projection code from AlphaEdit achieve better accuracy across all semantics. It also indicates that some semantics are more challenging to edit than others. However, even in these more difficult cases, baseline methods enhanced with AlphaEdit's projection code still achieve over 90% accuracy.

C.5 Comparison between AlphaEdit and Memory-based Editing Methods

Although our AlphaEdit mainly focuses on the parameter-modifying editing method, we also hope to explore the advantages of our method compared with some mainstream memory-based editing methods. Specifically, we select SERAC ([7]), GRACE ([14]), and MELO ([13]) as the representative baselines of the memory-based editing methods. The results are shown in Table 2. According to Table 2 we can summarize that:

- Across all models and tasks, AlphaEdit consistently achieves the highest scores in efficacy (Eff.) and generalization (Gen.). This indicates that AlphaEdit is highly effective at correctly applying the desired edits while maintaining robust generalization to the other knowledge. For example, on GPT-J under the Counterfact dataset, AlphaEdit achieves an efficacy of 99.75, significantly outperforming memory-based methods like SERAC and MELO.

- While AlphaEdit generally achieves competitive scores in specificity (Spe.) and fluency (Flu.), it does not always surpass the memory-based methods. However, we believe this trade-off is reasonable and acceptable because memory-based methods inherently rely on consuming storage space to better preserve existing knowledge.

C.6 Evaluation on Additional Base LLMs: Gemma and phi-1.5

To enhance evaluation diversity, we extended experiments to two additional base LLMs, Gemma ([31]) and phi-1.5 ([32]). We summarize the results in Table 3. These results demonstrate that AlphaEdit consistently outperforms MEMIT and RECT across key metrics on both the Counterfact and ZsRE datasets. Notably, on Gemma, AlphaEdit achieves the highest fluency (398.96) and consistency (32.91), reflecting its ability to maintain coherence and accuracy. Similarly, on phi-1.5, AlphaEdit excels in efficacy (70.79) and fluency (399.47), showcasing its adaptability to smaller, efficient models. These findings confirm AlphaEdit's robustness across diverse LLM architectures and its capability to deliver high-quality edits while preserving model integrity.

C.7 Evaluation on Expanding Benchmark: KnowEdit, LEME and MQUAKE

In this part, we selected two datasets from the KnowEdit ([36]) benchmark, namely wiki_recent and wikibio, for testing. During our experiments, we noticed that some samples within these datasets exhibit abnormally high norms in the hidden states when processed by the LLaMA3-8B-instruct model. These elevated norms are often accompanied by disproportionately large target value norms, which, if forcibly edited, could compromise the model's stability. To mitigate this issue, we implemented an automatic filtering mechanism to exclude samples with excessively high hidden state norms during the continuous editing process. Experimental results are presented in Table 4.

Additionally, we extended our evaluations to two critical datasets, LEME ([34]) and MQUAKE ([35]), to test AlphaEdit's performance in more challenging scenarios. LEME focuses on long-form generative tasks, emphasizing consistency, factual correctness, and lexical cohesion. MQUAKE, on the other hand, evaluates the ripple effects of factual updates using multi-hop reasoning questions. Results for these two datasets are summarized in Table 5.

According to Table 4 and Table 5 we can find that:

- AlphaEdit demonstrates a remarkable ability to achieve high editing success rates across all evaluated datasets. For instance, on the wiki_recent dataset, AlphaEdit achieves an impressive 96.10% editing success, which is significantly higher than the second-best method, RECT (82.47%). A similar trend is observed on wikibio, where AlphaEdit reaches 95.34%, outperforming RECT by a substantial margin.

- AlphaEdit demonstrates the best performance in both Multi-hop and Multi-hop (CoT) tasks, with scores of 9.14 and 9.75 respectively, significantly surpassing competing methods. This showcases its strong capability in handling complex reasoning tasks and ensuring logical consistency across interdependent facts.

- On LEME, AlphaEdit excels in all three metrics, showcasing its ability to generate accurate long-form outputs. Its consistently high performance across GPT-J and GPT2-XL reinforces its reliability in executing precise edits while maintaining the structural coherence and integrity of the generated text.

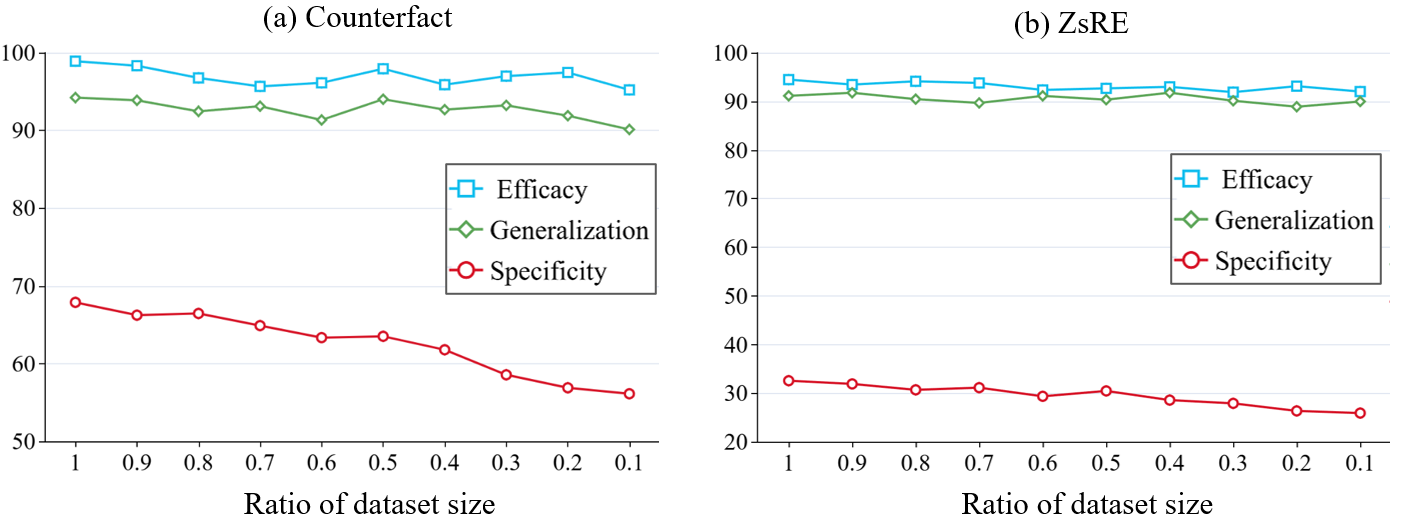

C.8 Impact of Dataset Size on AlphaEdit’s Performance

{To explore the relationship between dataset size for calculating K0 {\bm{K}}_0K0 and AlphaEdit's performance, we conduct additional experiments to evaluate the robustness of the model under reduced dataset conditions. Specifically, we progressively reduce the size of the dataset used to compute K0K_0K0 to proportions [0.9,0.8,0.7,…,0.1][0.9, 0.8, 0.7, \dots, 0.1][0.9,0.8,0.7,…,0.1] of its original size. The goal is to analyze the impact of dataset size on three key metrics: Efficacy, Generalization, and Specificity. All the results are summarized in Table 6. To further illustrate trend changes, we select the results for LLaMA3 and visualized them using line charts, as presented in Figure 11. According to Figure 11 we can find that:

- As the dataset size decreased, both Efficacy and Generalization demonstrate notable stability. Even at only 10% of the original dataset size, the drop in these metrics is negligible (less than 5%), suggesting that AlphaEdit effectively generalizes to unseen data and remains efficient even with reduced data availability.

- In contrast, the Specificity metric experience a significant decline as the dataset size is reduced. When the dataset size is limited to just 10% of its original volume, Specificity drop by 11.76%, indicating that the model's ability to store neighborhood knowledge heavily relies on the availability of a sufficiently large dataset.

C.9 Runtime Evaluation of AlphaEdit

{The computational complexity of the null-space projection in AlphaEdit depends solely on the dimension of the hidden dimension d0d_0d0 within the base LLM. Specifically, calculating the null-space projection matrix only requires operations on K0K0T∈Rd0×d0 {\bm{K}}_0 {\bm{K}}_0^T \in \mathbb{R}^{d_0 \times d_0}K0K0T∈Rd0×d0, which are independent of the number of layers, model size, or the knowledge base size.

To empirically validate the scalability of our method, we measured the average runtime for performing 100 edits with AlphaEdit and MEMIT on three LLMs with different model sizes and knowledge bases: LLaMA3, GPT-J, and GPT2-XL. The results are summarized in Table 7.

From these results, it is evident that AlphaEdit does not incur additional runtime overhead compared to MEMIT, even as the model size or knowledge base grows. This supports our claim that the null-space projection method is highly scalable and practical for large-scale model editing tasks.

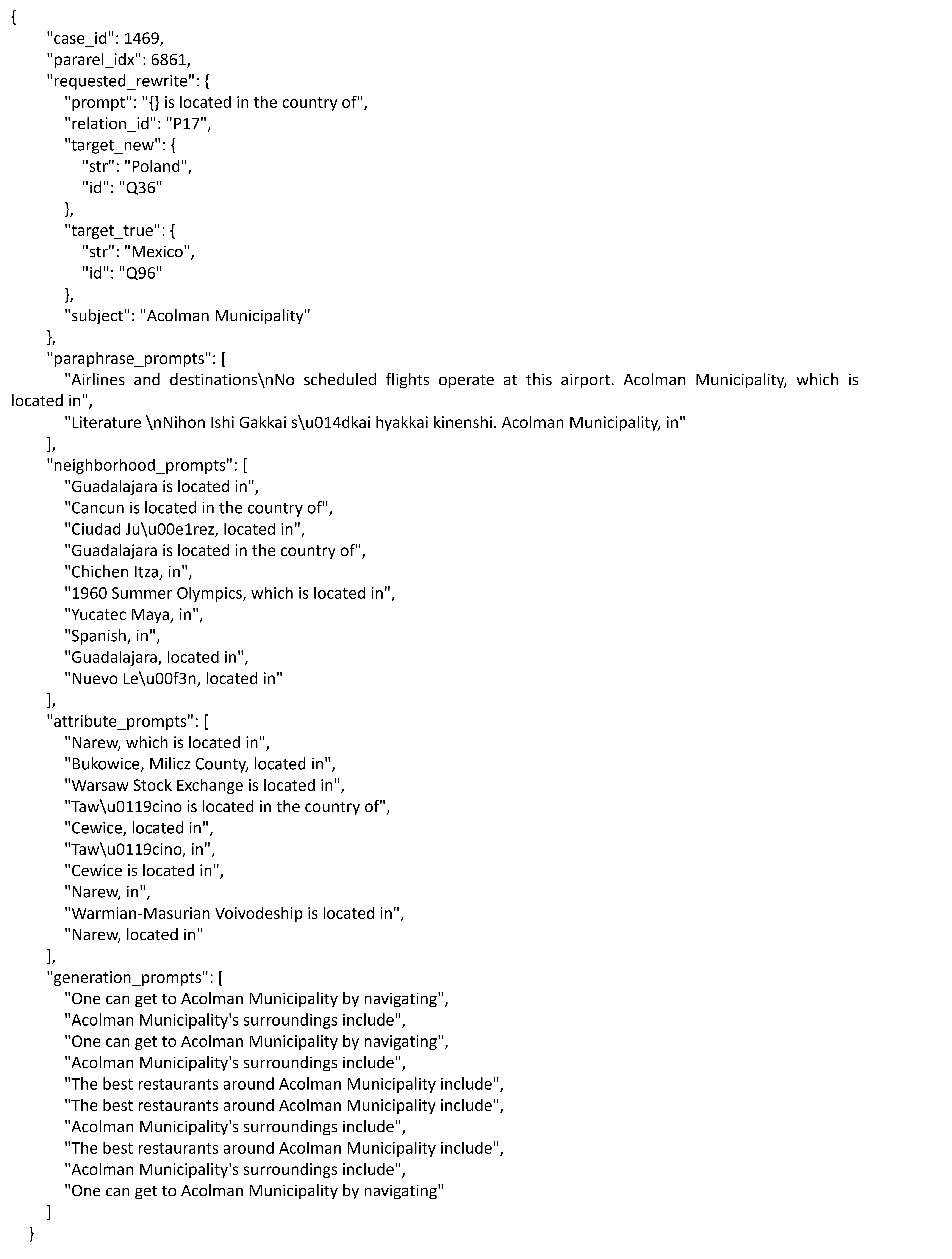

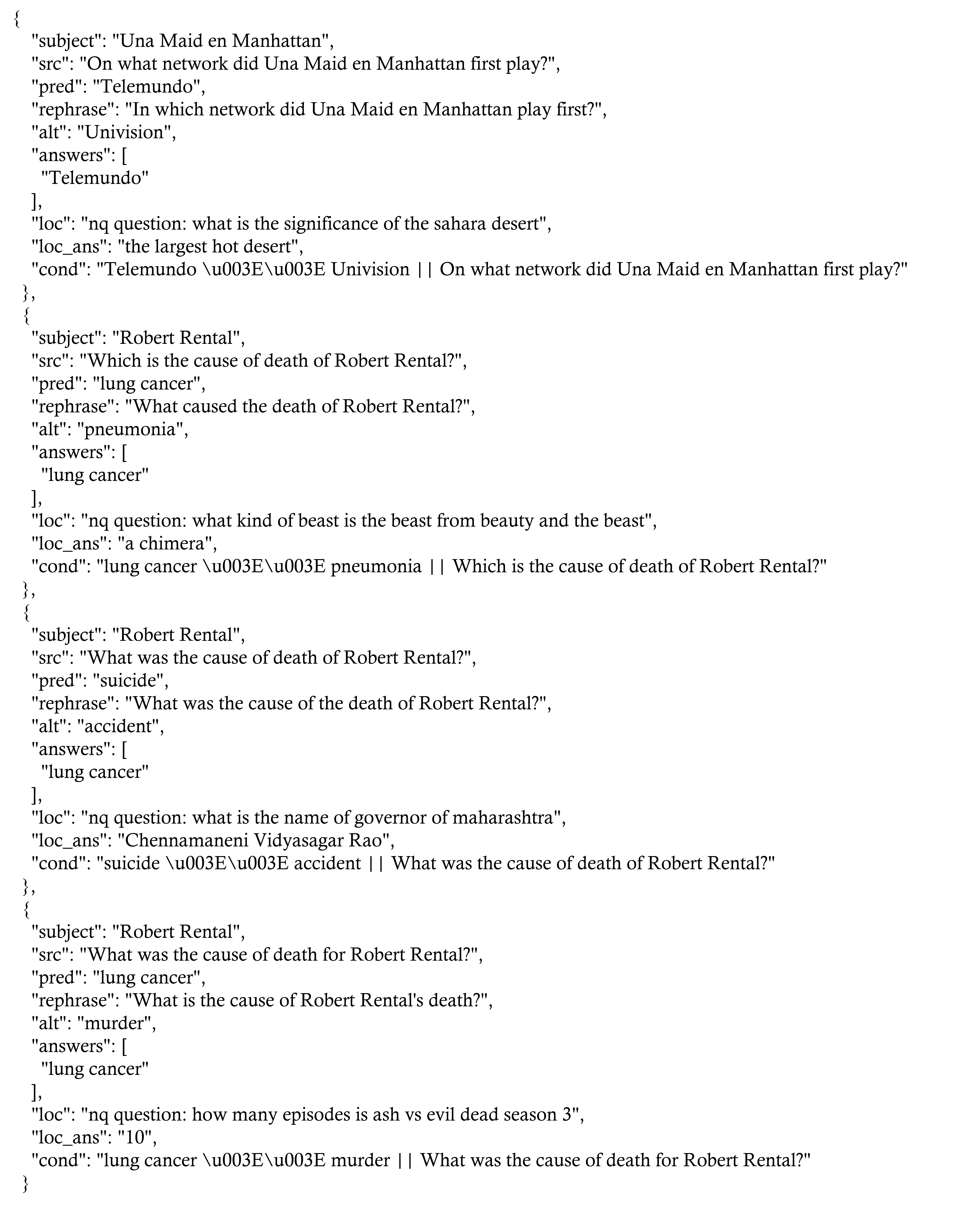

D. Visualizing the Counterfact and ZSRE Datasets Through Examples

To help readers unfamiliar with model editing tasks better understand the Counterfact and ZSRE datasets, we provide two examples from them in Figure 12 and Figure 13. These examples illustrate the types of modifications and factual updates applied to the models during the editing process.

References