Efficient Rectification of Neuro-Symbolic Reasoning Inconsistencies by Abductive Reflection

Show me an executive summary.

Purpose and context

Neural networks can solve complex problems quickly but often produce outputs that violate domain rules and knowledge. Existing neuro-symbolic AI methods that combine neural networks with logical reasoning either weaken the symbolic reasoning or require computationally expensive processes to fix these errors. This work introduces Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl), a new method that efficiently identifies and corrects errors in neural network outputs by using a "reflection mechanism" trained directly from domain knowledge. The goal is to achieve high accuracy with less training data and faster inference while maintaining the full power of both neural networks and symbolic reasoning.

What was done

The research team developed ABL-Refl, which adds a reflection layer to standard neural networks. This layer generates a "reflection vector" that flags which parts of the neural network's output likely violate domain knowledge constraints. The flagged positions are then corrected using symbolic reasoning (abduction) based on a knowledge base containing domain rules. Unlike previous methods that must search through exponentially many possible corrections, ABL-Refl narrows the search space by focusing only on flagged errors, requiring just one call to the symbolic solver instead of billions.

The reflection vector is trained using a reinforcement learning approach that measures how much flagging and correcting errors improves consistency with the knowledge base. Importantly, this training uses only the domain knowledge itself, not additional labeled data. The method was tested on three types of problems: solving Sudoku puzzles from symbolic inputs, solving Sudoku from handwritten digit images, and finding maximum cliques and independent sets in graphs.

Key findings

ABL-Refl significantly outperformed existing neuro-symbolic methods across all tasks. For symbolic Sudoku, it achieved 97.4% accuracy compared to 76.5% for the best baseline, while maintaining similar inference speed. With only 2,000 labeled training examples instead of 20,000, ABL-Refl still exceeded the accuracy of baselines trained on the full dataset. For visual Sudoku (from handwritten digits), accuracy reached 93.5% versus 63.5% for the closest competitor. On graph optimization problems with up to 74 nodes and 2,457 edges per graph, ABL-Refl achieved near-perfect approximation ratios (0.98-0.99) while baselines ranged from 0.78 to 0.93.

The reflection mechanism proved far more effective than simply using neural network confidence scores to identify errors. It correctly identified 99% of actual errors, compared to only 83% when using confidence scores, and did so with consistent inference times around 0.2 seconds. In contrast, the previous ABL consistency optimization approach required over an hour to process 1,000 test cases due to making billions of queries to the symbolic solver.

What the findings mean

These results demonstrate that explicitly training neural networks to detect their own errors using domain knowledge creates a practical bridge between fast pattern recognition and reliable logical reasoning. The substantial reduction in required training data (up to 90% less) and training time (reaching high accuracy in just a few epochs) means the method can be deployed with less upfront investment in data collection and annotation. The maintained or improved inference speed, despite incorporating symbolic reasoning, makes the approach viable for real-time or large-scale applications.

The method's effectiveness across different input types (symbols, images, graphs) and knowledge representations (propositional logic, first-order logic, mathematical constraints) indicates broad applicability. The ability to handle high-dimensional problems that stymied previous methods expands the range of practical use cases.

Recommendations and next steps

Organizations should consider ABL-Refl for applications where outputs must satisfy strict domain constraints, such as automated planning, code generation, medical diagnosis systems, or any task where errors have significant consequences. The method is particularly valuable when labeled training data is expensive or scarce but domain knowledge is well-defined.

For implementation, set the hyperparameter C (which controls how much to trust the neural network versus symbolic reasoning) between 0.6 and 0.9; the specific value is not critical within this range and can balance accuracy against computation time based on application needs. Start with existing neural network architectures and add the reflection layer without major redesign.

The next research priority should be applying ABL-Refl to large language models to identify and correct errors in their text generation, improving reliability for high-stakes applications. Additional work should explore scaling to even larger problem sizes and more complex knowledge bases, and investigate whether the reflection mechanism can transfer across related tasks.

Limitations and confidence

The experiments used well-defined, relatively structured problems with clear knowledge bases. Performance on less structured domains or with incomplete or contradictory knowledge bases is unknown. The method requires access to a symbolic solver appropriate for the knowledge representation, which may not exist or may be slow for certain types of constraints. The REINFORCE training algorithm can be sensitive to reward design, though the consistency measurement used here proved robust.

Confidence in the core results is high, supported by consistent improvements across multiple problem types and datasets with small variance across repeated runs. The claimed benefits for real-world deployment are based on experimental evidence but have not been validated in production systems. The estimated training data reduction is solid, but the exact reduction possible will depend on problem complexity and the quality of the knowledge base.

Authors: Wen-Chao Hu1,2^{1,2}1,2, Wang-Zhou Dai1,3^{1,3}1,3, Yuan Jiang1,2^{1,2}1,2, Zhi-Hua Zhou1,2^{1,2}1,2

1^11National Key Laboratory for Novel Software Technology, Nanjing University, China

2^22School of Artificial Intelligence, Nanjing University, China

3^33School of Intelligence Science and Technology, Nanjing University, China

{huwc, daiwz, jiangy, zhouzh}@lamda.nju.edu.cn

Abstract

Neuro-Symbolic (NeSy) AI could be regarded as an analogy to human dual-process cognition, modeling the intuitive System 1 with neural networks and the algorithmic System 2 with symbolic reasoning. However, for complex learning targets, NeSy systems often generate outputs inconsistent with domain knowledge and it is challenging to rectify them. Inspired by the human Cognitive Reflection, which promptly detects errors in our intuitive response and revises them by invoking the System 2 reasoning, we propose to improve NeSy systems by introducing Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl) based on the Abductive Learning (ABL) framework. ABL-Refl leverages domain knowledge to abduce a reflection vector during training, which can then flag potential errors in the neural network outputs and invoke abduction to rectify them and generate consistent outputs during inference. ABL-Refl is highly efficient in contrast to previous ABL implementations. Experiments show that ABL-Refl outperforms state-of-the-art NeSy methods, achieving excellent accuracy with fewer training resources and enhanced efficiency.

1 Introduction

In this section, the challenge of reconciling inconsistencies between neural network outputs and domain knowledge in Neuro-Symbolic AI systems is addressed through a novel framework called Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl). Neuro-symbolic systems mirror human dual-process cognition, with neural networks acting as fast, intuitive System 1 and symbolic reasoning as deliberate System 2, but neural networks often produce outputs that violate domain constraints in complex tasks. While existing approaches either relax symbolic knowledge into neural constraints or approximate logic within networks—losing full reasoning power—the Abductive Learning framework preserves both components but suffers from computationally expensive consistency optimization. Drawing inspiration from human cognitive reflection, which rapidly detects and corrects intuitive errors by selectively invoking deliberate reasoning, ABL-Refl introduces a reflection mechanism that flags potential inconsistencies and triggers targeted abduction during inference. This reflection vector is trained using domain knowledge without requiring additional labeled data, achieving superior accuracy with reduced computational resources compared to state-of-the-art methods.

Human decision-making is generally recognized as an interaction between two systems: System 1 quickly generates an intuitive response, and System 2 engages in further algorithmic and slow reasoning [1, 2]. In Neuro-Symbolic (NeSy) Artificial Intelligence (AI), neural networks often resemble System 1 for rapid pattern recognition, and symbolic reasoning mirrors System 2 to leverage domain knowledge and handle complex problems thoughtfully, yet in a slower and more controlled way [3]. Like human System 1 reasoning, when facing complicated tasks, neural networks often produce unreliable outputs which cause inconsistencies with domain knowledge. These inconsistencies can then be reconciled with the help of the symbolic reasoning counterpart [4].

To achieve the above process, some methods relax symbolic domain knowledge as neural network constraints [5, 6], some attempt to approximate logical calculus using distributed representations within neural networks [7]. However, a loss of full symbolic reasoning ability often occurs during these relaxation or approximation, hampering the ability of generating reliable output.

Abductive Learning (ABL) [8, 9] is a framework for bridging machine learning and logical reasoning while preserving full expressive power in each side. In ABL, the machine learning component first converts raw data into primitive symbolic outputs. These outputs can be utilized by the symbolic reasoning component, which leverages domain knowledge and performs abduction to generate a revised, more reliable output. However, previous implementations of ABL require a highly discrete combinatorial consistency optimization before applying abduction, and this optimization has high complexity which encumbers, thereby severely limiting the efficiency and applicability to large-scale scenarios.

Human reasoning naturally exploits both sides efficiently, a hypothetical model for this process is called Cognitive Reflection, where the fast System 1 thinking is called to quickly generate an approximate over-all solution, and then seamlessly hands the complicated parts to System 2 [1]. The key to this process is the reflection mechanism, which promptly detects which part in the intuitive response may contain inconsistencies with domain knowledge and invokes System 2 to rectify them. This reflection typically positively associates with System 2 capabilities, as both are closely linked to an individual's mastery of domain knowledge [10]. Following the reflection, the process of the step-by-step formal reasoning becomes less complex: With a largely reduced search space, deriving the correct solution for System 2 becomes straightforward.

Inspired by this phenomenon, we propose a general enhancement, Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl). Based on ABL framework, ABL-Refl preserves full expressive power of neural networks and symbolic reasoning, while replacing the time-consuming consistency optimization with the reflection mechanism, thereby significantly improves efficiency and applicability. Specifically, in ABL-Refl, a reflection vector is concurrently generated with the neural network intuitive output, which flags potential errors in the output and invokes symbolic reasoning to perform abduction, thereby rectifying these errors and generating a new output that is more consistent with domain knowledge. During model training, the training information for the reflection derives from domain knowledge. In essence, the reflection vector is abduced from domain knowledge and serves as an attention mechanism for narrowing the problem space of symbolic reasoning. The reflection can be trained unsupervisedly, requiring only the same amount of domain knowledge as state-of-the-art NeSy systems without generating extra training data.

We validate the effectiveness of ABL-Refl in solving Sudoku NeSy benchmarks in both symbolic and visual forms. Compared to previous NeSy methods, ABL-Refl performs significantly better, achieving higher reasoning accuracy efficiently with fewer training resources. We also compare our method to symbolic solvers, and show that the reduced search space in ABL-Refl improves the reasoning efficiency. Further experiments on solving combinatorial optimization on graphs validate that ABL-Refl can handle diverse types of data in varied dimensions, and exploit knowledge base in different forms.

2 Related Work

In this section, recent progress in neuro-symbolic AI reveals multiple approaches to enhancing neural networks with symbolic reasoning, each with distinct limitations. Methods using differentiable fuzzy logic or relaxing symbolic knowledge as neural network constraints tend to soften symbolic reasoning requirements, compromising output reliability. Models like DeepProbLog and NeurASP interpret neural outputs as distributions over symbols before applying symbolic solvers, incurring substantial computational costs. Abductive Learning (ABL) balances machine learning and logical reasoning while preserving full expressive power on both sides, offering an open-source toolkit with practical applications, but suffers from high-complexity consistency optimization that limits scalability. Related work following prediction-error-reasoning processes remains confined to narrow knowledge domains or minimal world models. Cornelio et al. use error selection modules requiring large pre-generated synthetic datasets, whereas the proposed approach automatically abduces reflection vectors during training, eliminating this preprocessing burden while maintaining integration between neural and symbolic components.

Recently, there has been notable progress in enhancing neural networks with reliable symbolic reasoning. Some methods use differentiable fuzzy logic [11, 12] or relax symbolic domain knowledge as constraints for neural network training [5, 6, 13, 14], while others learn constraints within neural networks by approximating logic reasoning with distributed representations [15, 16, 7]. These models tend to soften the requirements in symbolic reasoning, impacting the reliability of output generation. Models like DeepProbLog [17] and NeurASP [18] interpret the neural network output as a distribution over symbols and then apply a symbolic solver, incurring substantial computational costs. Abductive Learning (ABL) [8, 9] attempts to integrate machine learning and logical reasoning in a balanced and mutually supporting way. It features an easy-to-use open-source toolkit [19] with many practical applications [20, 21, 22, 23]. However, the consistency optimization is with high complexity.

Another category of work related to our study also follows a similar process of prediction, error identification, and reasoning [24, 25, 26]. These methods are usually constrained in a narrow scope of domain knowledge, confined to specific mathematical problems or are bounded within a minimal world model.

Cornelio el al. [27] generates a selection module to identify errors requiring symbolic reasoning rectification. In constrast to their approach which requires the preparation of a large synthetic dataset in advance, our approach automatically abduces the reflection vector during model training.

3 Abductive Reflection

In this section, the authors address the computational bottleneck in traditional Abductive Learning (ABL), where consistency optimization requires exponentially scaling combinatorial searches that repeatedly query the knowledge base. They propose Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl), which replaces this expensive optimization with an efficient reflection mechanism inspired by human cognitive reflection. The method augments a neural network with a reflection layer that generates a binary vector concurrently with the intuitive output, flagging which elements likely contain errors inconsistent with domain knowledge. During training, this reflection vector is abduced directly from the knowledge base using a consistency improvement reward optimized via REINFORCE, combined with a size penalty to minimize unnecessary abduction invocations. Crucially, the reflection training requires no labeled data beyond what standard neuro-symbolic systems use, as it leverages domain knowledge directly. This architecture narrows the search space for symbolic reasoning to a single abduction call, dramatically improving efficiency while maintaining full expressive power in both neural and symbolic components.

This section presents problem setting and the Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl) method.

3.1 Problem Setting

The main task of this paper is as follows: The input is raw data x\boldsymbol{x}x, which can be in either symbolic or sub-symbolic form, and the target output is y=[y1,y2,…,yn]\boldsymbol{y}=\left[y_1, y_2, \dots, y_n\right]y=[y1,y2,…,yn], with each yiy_iyi being a symbol from a set Y\mathcal{Y}Y that contains all possible output symbols. We assume two key components at our disposal: neural network fff and domain knowledge base KB\mathcal{KB}KB. fff can directly map x\boldsymbol{x}x to y\boldsymbol{y}y, and KB\mathcal{KB}KB holds constraints between the symbols in y\boldsymbol{y}y. KB\mathcal{KB}KB can assume various forms, including propositional logic, first-order logic, mathematical or physical equations, etc., and can perform symbolic reasoning operations by exploiting the corresponding symbolic solver. The output y\boldsymbol{y}y should adhere to the constraints in KB\mathcal{KB}KB, otherwise it will inevitably contain errors that lead to inconsistencies with the domain knowledge and incorrect reasoning results.

This problem type has broad applications. For example, it can be used to solve Sudoku puzzles, where the output y\boldsymbol{{y}}y consists of n=81n=81n=81 symbols from the set Y={1,2,…,9}\mathcal{Y}=\{1, 2, \dots, 9\}Y={1,2,…,9}, and the constraints in KB\mathcal{KB}KB are the rules of Sudoku. It can also be applied in deploying generative models for text generation, gene prediction, mathematical problem-solving, etc., producing outputs that adhere to intricate commonsense, biological, or mathematical logics in KB\mathcal{KB}KB.

3.2 Brief Introduction to Abductive Learning

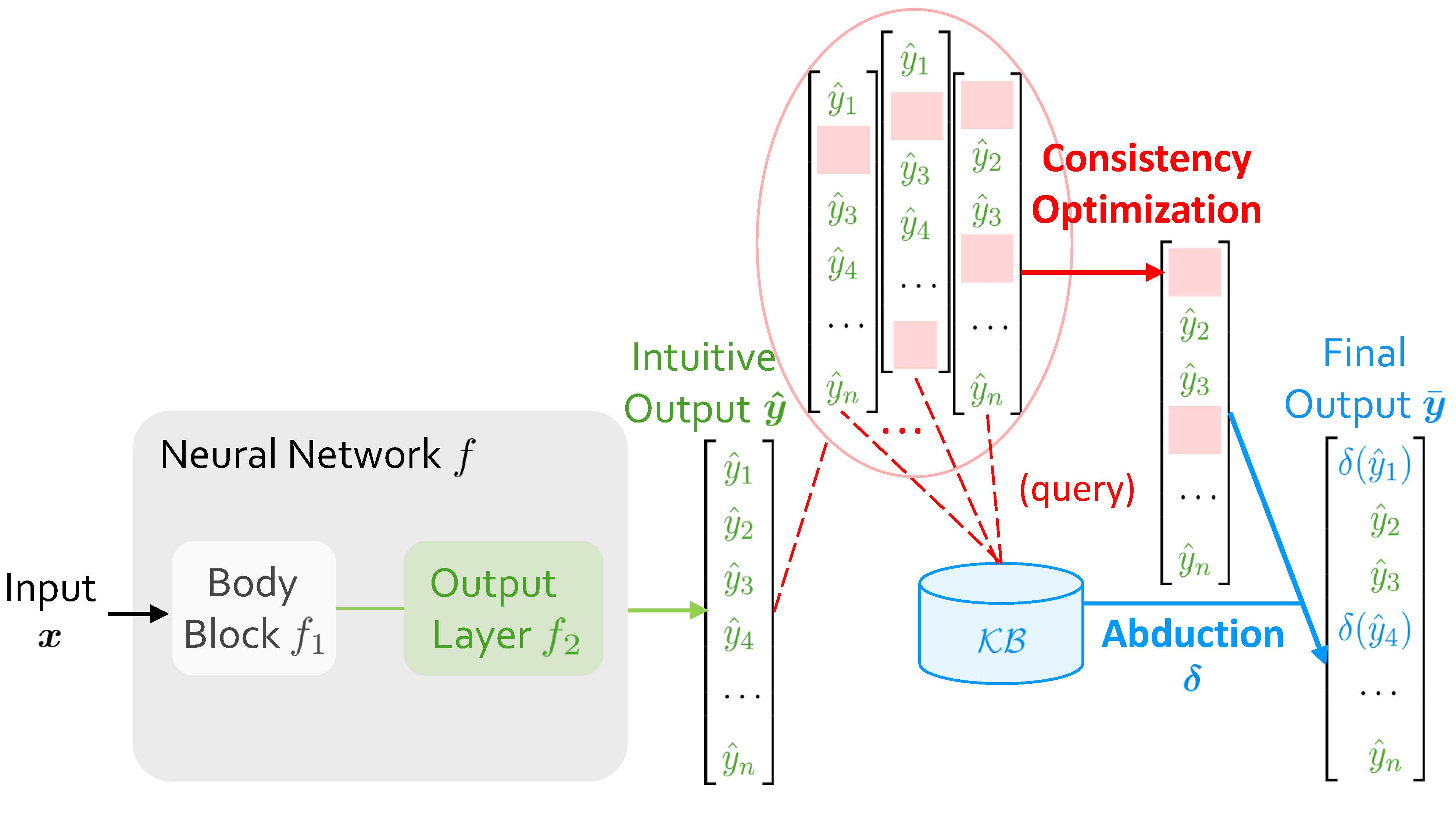

When Abductive Learning (ABL) receives an input x\boldsymbol{x}x, it initially employs fff to map x\boldsymbol{x}x into an intuitive output y^=[y^1,y^2,…,y^n]\boldsymbol{\hat{y}} = \left[\hat{y}_1, \hat{y}_2, \dots, \hat{y}_n\right]y^=[y^1,y^2,…,y^n]. When fff is under-trained, y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^ might contain errors leading to inconsistencies with KB\mathcal{KB}KB. ABL then tries to rectify them, and obtains a revised yˉ\boldsymbol{\bar{y}}yˉ. As shown in Figure 1, the final output, yˉ\boldsymbol{\bar{y}}yˉ, consists of two parts: the green part retains the results from neural network, and the blue part is the modified result obtained by abduction, a basic form of symbolic reasoning that seeks plausible explanations for observations based on KB\mathcal{KB}KB.

Specifically, the process of obtaining yˉ\boldsymbol{\bar{y}}yˉ can be divided into two sequential steps. The first step, consistency optimization, determines which positions in y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^ include elements that contain errors causing inconsistencies, so that performing abduction at these positions will yield a yˉ\boldsymbol{\bar{y}}yˉ consistent with KB\mathcal{KB}KB. Essentially, this process is pinpointing propositions (or ground atoms, etc.) which have incorrect truth assignments, and most neuro-symbolic tasks can be formalized into this form. Once these positions are determined, the second step is rectifying by abduction, which then becomes easy for KB\mathcal{KB}KB and its corresponding symbolic solver.

Challenge.

In previous ABL, consistency optimization has always been a computational bottleneck. It operates as an external module using zeroth-order optimization methods, independent from both fff and KB\mathcal{KB}KB [28, 9]. For each time of inference, it involves repetitively selecting various possible positions and querying the KB\mathcal{KB}KB to see if a consistent result can be inferred. Each query involves an invocation of KB\mathcal{KB}KB for slow symbolic reasoning. Also, since it is a complex combinatorial problem with a highly discrete nature, the number of such queries required escalates exponentially as data scale increases. This large number leads to a marked increase in time consumption, hence confines the applicability of ABL to only small datasets, usually those with output dimension nnn less than 10.

3.3 Architecture

To address the challenges above, we propose Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl). In this section, we will provide a detailed description of its architecture.

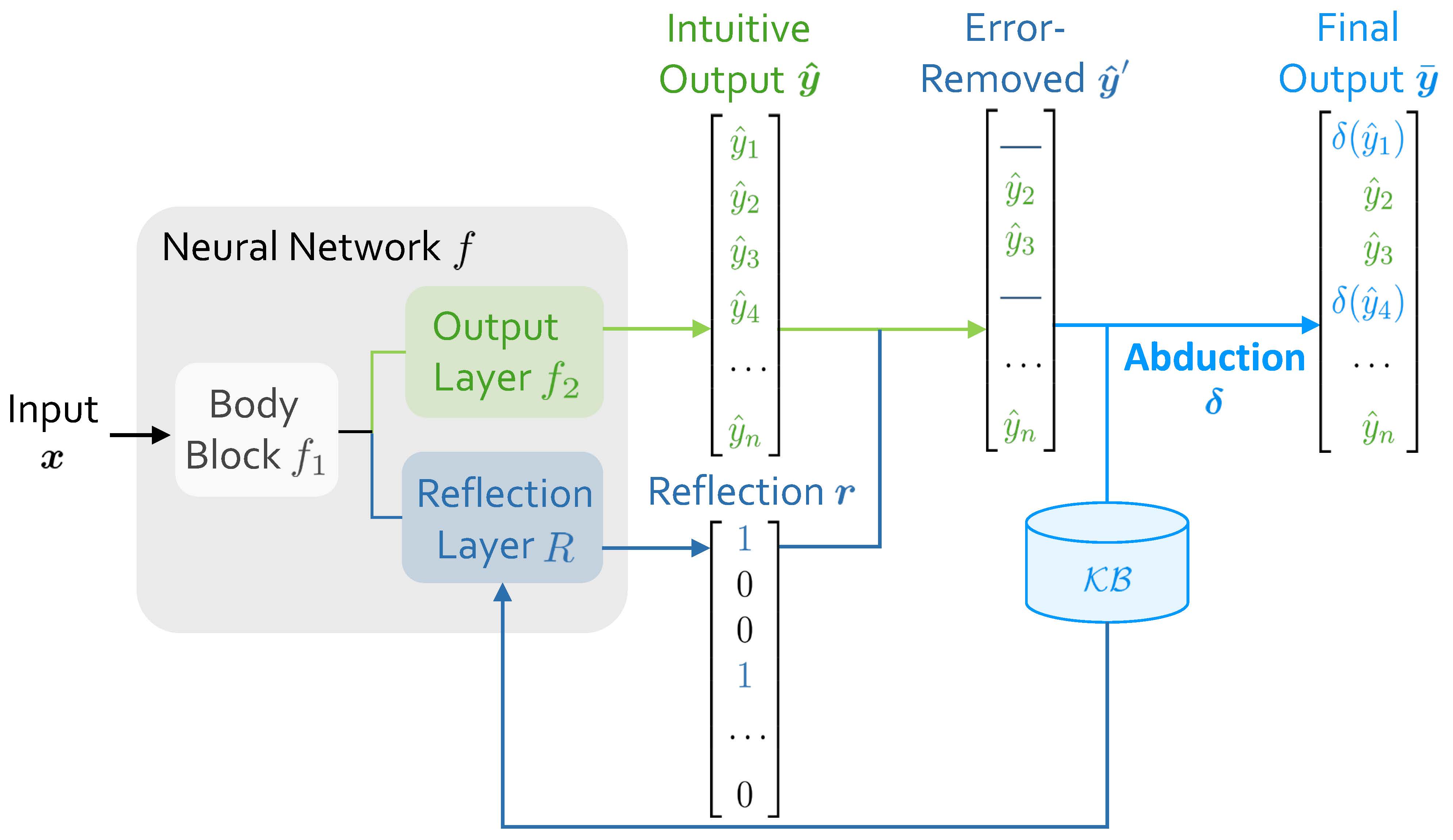

Let's first revisit the role of the neural network fff when we map the input to symbols from the set Y\mathcal{Y}Y. Typically, the raw data is first passed through the body block of the network, denoted by f1f_1f1, resulting in a high-dimensional embedding which encapsulates a wealth of feature information of the raw data. The form of f1f_1f1 varies, including structures like recurrent layers, graph convolution layers, or Transformers, etc. The result of f1f_1f1 is subsequently passed into several layers, usually linear layers, denoted by f2f_2f2, to obtain the intuitive output: y^=argmax(f2(f1(x)))∈Yn\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}=\text{argmax}(f_2(f_1(\boldsymbol{x})))\in\mathcal{Y}^ny^=argmax(f2(f1(x)))∈Yn.

Besides the structure described above, as shown in Figure 2, our architecture further incorporates a reflection layer RRR after the body block f1f_1f1, generating a reflection vector: r=argmax(R(f1(x)))∈{0,1}n\boldsymbol{r}=\text{argmax}(R(f_1(\boldsymbol{x})))\in \{0, 1\}^nr=argmax(R(f1(x)))∈{0,1}n. The reflection layer RRR and reflection vector r\boldsymbol{r}r together constitute the reflection mechanism. This vector r\boldsymbol{r}r has the same dimensionality nnn as the intuitive output y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^, and each element, rir_iri, acts as a binary classifier to indicate whether the corresponding element y^i\hat{y}_iy^i is an error leading to inconsistencies with KB\mathcal{KB}KB (flagged as 1 for an error, and 0 otherwise). The reflection vector r\boldsymbol{r}r is generated concurrently with the intuitive response during inference, resonating with human cognition where cognitive reflection typically forms right upon generation of an intuitive response [1].

With the initial intuitive output y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^ and the corresponding reflection vector r\boldsymbol{r}r, we seamlessly obtain the error-removed output y^′\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}^\primey^′: In y^′\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}^\primey^′, elements flagged as error by r\boldsymbol{r}r are removed and left as blanks, while the rest are retained. Subsequently, KB\mathcal{KB}KB applies abduction to fill in these blanks, thereby generating an output yˉ\boldsymbol{\bar{y}}yˉ that is consistent with KB\mathcal{KB}KB. That is:

where δ\deltaδ denotes abduction. We treat yˉ=[yˉ1,yˉ2,…,yˉn]\boldsymbol{\bar{y}}= \left[\bar{y}_1, \bar{y}_2, \dots, \bar{y}_n\right]yˉ=[yˉ1,yˉ2,…,yˉn] as the final output.

During model training, the reflection is abduced from KB\mathcal{KB}KB by directly leveraging information from domain knowledge (discussed later in Section 3.4). It can be seen as an attention mechanism generated from neural networks, which can help quickly focus symbolic reasoning specifically on areas it identifies as errors, hence largely narrowing the problem space of deliberate symbolic reasoning [29].

Benefits.

Compared to previous ABL implementations, ABL-Refl replaces the zeroth-order consistency optimization module with the reflection mechanism to address the computational bottleneck. In this way, the need for a substantial number of querying KB\mathcal{KB}KB is mitigated: After promptly pinpointing inconsistencies in System 1 output, regardless of the data scale, only a single invocation of KB\mathcal{KB}KB is required to obtain a rectified and more consistent output.

Another thing worth noticing is that, in the architecture, the reflection layer directly connects to the body block, which helps leveraging information from the embeddings and linking more closely with the raw data. Therefore, the reflection vector r\boldsymbol{r}r establishes a more direct and tighter bridge between raw data and domain knowledge.

3.4 Training Paradigm

In this section, we will discuss how to train the ABL-Refl method, especially the reflection in it.

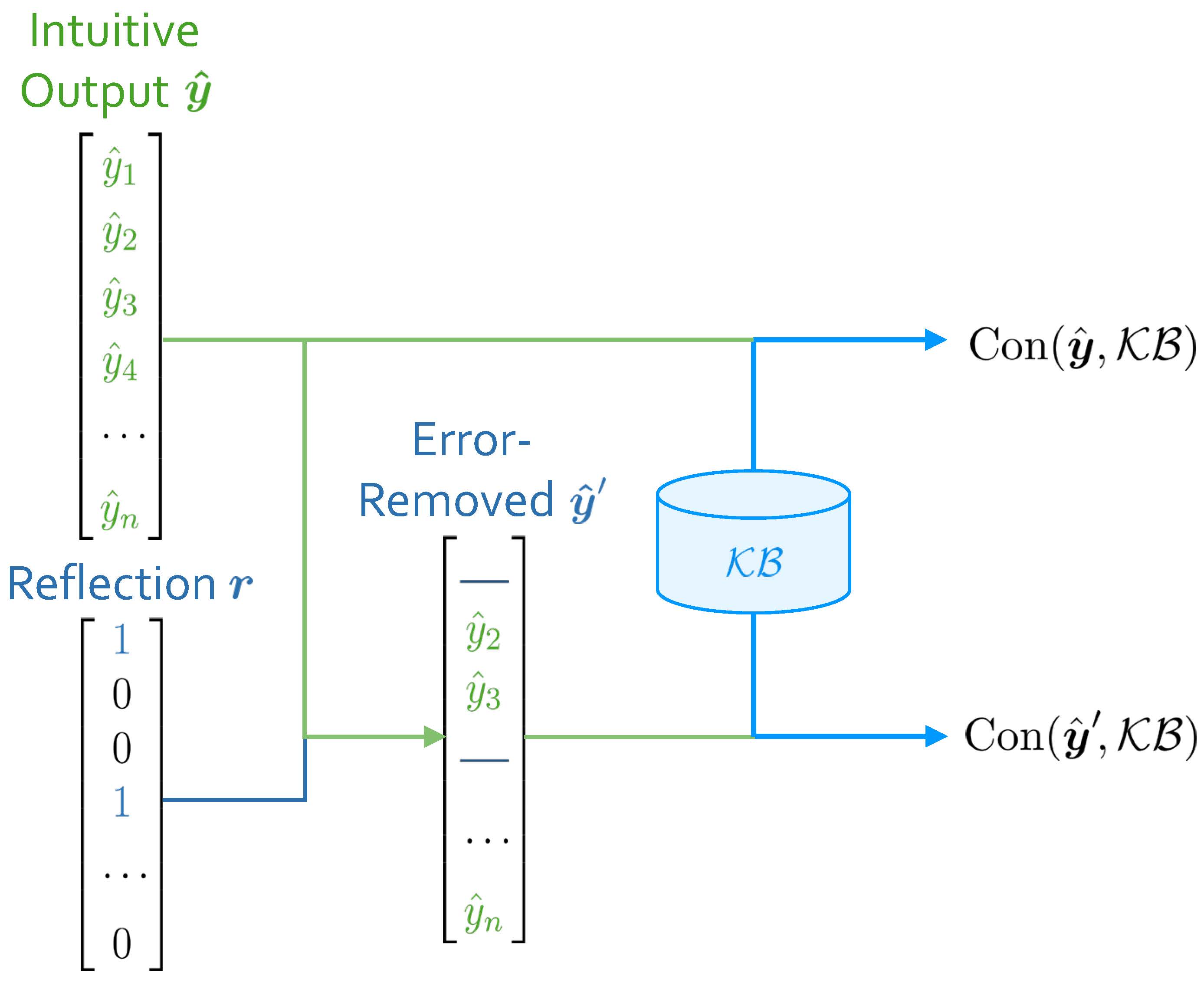

In ABL-Refl, when each input x\boldsymbol{x}x is processed by the neural network, we obtain the intuitive output y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^ and the reflection vector r\boldsymbol{r}r, and subsequently obtain the error-removed (by r\boldsymbol{r}r) output y^′\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}^\primey^′. With y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^ and y^′\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}^\primey^′, we can measure their consistency with KB\mathcal{KB}KB, respectively. We denote these consistency measurements as Con(y^,KB)\text{Con}(\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}, \mathcal{KB})Con(y^,KB) and Con(y^′,KB)\text{Con}(\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}^\prime, \mathcal{KB})Con(y^′,KB), as shown in Figure 3. For a simplest example, if all elements in y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^ (or y^′\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}^\primey^′) adhere to constraints in KB\mathcal{KB}KB, the consistency measurement is 1; otherwise, it is 0.

Consequently, the improvement in consistency measurement after reflection, as denoted by

naturally indicates the effectiveness of the reflection vector: A higher value of it signifies that reflection r\boldsymbol{r}r can more effectively detect inconsistencies within y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^. Our training goal is to guide the neural network's parameters towards generating reflections that can maximize this value. Given that ΔConr(y^)\Delta\text{Con}_{\boldsymbol{r}}(\boldsymbol{\hat{y}})ΔConr(y^) is usually a discrete value, we employ the REINFORCE algorithm to achieve this goal [30], which optimizes the policy (implicitly defined by neural network fff) through maximizing a specified reward — in this case, ΔConr(y^)\Delta\text{Con}_{\boldsymbol{r}}(\boldsymbol{\hat{y}})ΔConr(y^). This process leads to the following consistency loss:

where θ\thetaθ are parameters of neural network fff.

Additionally, given that the time abduction required often escalates with problem size, we want to invoke it judiciously during inference, applying it only when it is truly necessary. Therefore, we aim to avoid the reflection vector from flagging too many elements in y^\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}y^ as error. To achieve this, we then introduce a reflection size loss:

where Φ(a)≜max(0,a)2\Phi(a)\triangleq \max(0, a)^2Φ(a)≜max(0,a)2 and CCC is a hyperparameter ranging between 0 and 1. When CCC is set at a higher value, the reflection vector tends to retain a greater number of intuitive output elements instead of flagging them as error and delegating to abduction.

In addition to the above-mentioned training methods, using labeled data, we employ data-driven supervised training methods similar to common neural network training paradigm. The loss function in this process, e.g., cross-entropy loss, is denoted by Llabeled(x,y)L_{labeled}(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y})Llabeled(x,y).

Therefore, combining all the training loss, the total loss for ABL-Refl is represented as follows:

where α\alphaα and β\betaβ are hyperparameters, Dl={(x1,y1),(x2,y2),… }D_l=\{(\boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{y}_1), (\boldsymbol{x}_2, \boldsymbol{y}_2), \dots\}Dl={(x1,y1),(x2,y2),…} are the labeled datasets and Du={x1,x2,… }D_u=\{\boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots\}Du={x1,x2,…} are the unlabeled datasets.

Note that neither LconL_{con}Lcon nor LsizeL_{size}Lsize, which are loss functions specifically related to the reflection, incorporate information from the data label. Instead, we leverage training information directly from KB\mathcal{KB}KB to train the reflection. Also, despite sharing the prior feature layers, the output layer f2f_2f2 and reflection layer RRR utilize different training information, thereby decoupling the objectives of intuitive problem-solving and inconsistency reflection.

4 Experiments

In this section, the authors conduct experiments to validate ABL-Refl's effectiveness across three progressively challenging domains: symbolic Sudoku solving, visual Sudoku with MNIST images, and NP-hard graph combinatorial optimization problems. The experiments address four key questions regarding performance, resource efficiency, reasoning acceleration, and broad applicability. On symbolic Sudoku, ABL-Refl achieves over 20% higher accuracy than baselines while requiring significantly less training time and labeled data, demonstrating that reflection-guided abduction effectively narrows the symbolic reasoning search space. The visual Sudoku task confirms that ABL-Refl handles both symbolic and sub-symbolic inputs through end-to-end training. Finally, on maximum clique problems across multiple graph datasets, the method achieves near-perfect approximation ratios even as data scales increase, showing that ABL-Refl works with diverse knowledge representations beyond logic, including basic mathematical formulations, and maintains high accuracy in high-dimensional settings where previous methods struggle.

In this section, we will conduct several experiments. First, we will test our method on the NeSy benchmark task of solving Sudoku to comprehensively verify its effectiveness. Next, we will change the Sudoku input from symbols to images, which requires integrating and simultaneous reasoning with both sub-symbolic and symbolic elements, representing one of the most challenging tasks in this field. Finally, we will tackle NP-hard combinatorial optimization problems on graphs, using a knowledge base of only mathematical definitions, to demonstrate our method's versatility. Through these experiments, we aim to answer the following questions:

- Q1 Compared to existing neuro-symbolic learning methods, can ABL-Refl achieve better performance in tasks requiring complex reasoning?

- Q2 Can ABL-Refl reduce the training resources required?

- Q3 Can ABL-Refl narrow the problem space for symbolic reasoning to achieve acceleration?

- Q4 Does ABL-Refl possess the capability for broad application, such as handling diverse data scenarios or various forms of domain knowledge?

All experiments are performed on a server with Intel Xeon Gold 6226R CPU and Tesla A100 GPU. In our experiments, we simply set hyperparameters α\alphaα and β\betaβ in Eq. (3) to 1, since adjusting them does not have a noticeable impact on the results. , and have provided discussions in Appendix C, demonstrating that setting it to a value within a broad moderate range (e.g., 0.6-0.9) would always be a recommended choice. All experiments are repeated 5 times.

4.1 Solving Sudoku

Dataset and Setting.

This task aims to solve a 9 ×\times× 9 Sudoku: Given 81 digits of 0-9 (where 0 represents a blank space) in a 9 ×\times× 9 board, we aim to find a solution y∈{1,2,…,9}81\boldsymbol{y}\in\{1, 2, \dots, 9\}^{81}y∈{1,2,…,9}81 that adhere to the Sudoku rules: no duplicate numbers are allowed in any row, column, or 3 ×\times× 3 subgrid. In this section, we first consider inputs in symbolic form, x∈{0,1,…,9}81\boldsymbol{x}\in\{0, 1, \dots, 9\}^{81}x∈{0,1,…,9}81, and use datasets from a publicly available Kaggle site [31].

For the neural network fff, we use a simple graph neural network (GNN): the body block f1f_1f1 consists of one embedding layer and eight iterations of message-passing layers, resulting in a 128-dimensional embedding for each number, and then connects to both a linear output layer f2f_2f2 to obtain the intuitive output y^\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}y^ and a linear reflection layer RRR to obtain the reflection vector r{\boldsymbol{r}}r. We use the cross-entropy loss as LlabeledL_{labeled}Llabeled. For the domain knowledge base KB\mathcal{KB}KB, it contains the Sudoku rules mentioned above. We express KB\mathcal{KB}KB in the form of propositional logic and utilize the MiniSAT solver [32], an open-source SAT solver, as the symbolic solver to leverage KB\mathcal{KB}KB and perform abduction.

For the consistency measurement, we define it as follows: one point is awarded for each row, each column and each 3 ×\times× 3 subgrid with no duplicate numbers, additionally, ten points are awarded if the entire board has no inconsistencies with KB\mathcal{KB}KB. In this way, it is entirely based on KB\mathcal{KB}KB. Notice that we deviated from the 1 or 0 measurement example setup mentioned in Section 3.4 to avoid a predominance of zero values in ΔConr(y^)\Delta\text{Con}_{\boldsymbol{r}}(\boldsymbol{\hat{y}})ΔConr(y^) of Eq. (1), facilitating effective training with the REINFORCE algorithm. Similar considerations are applied in subsequent experiments.

Compared Methods and Results.

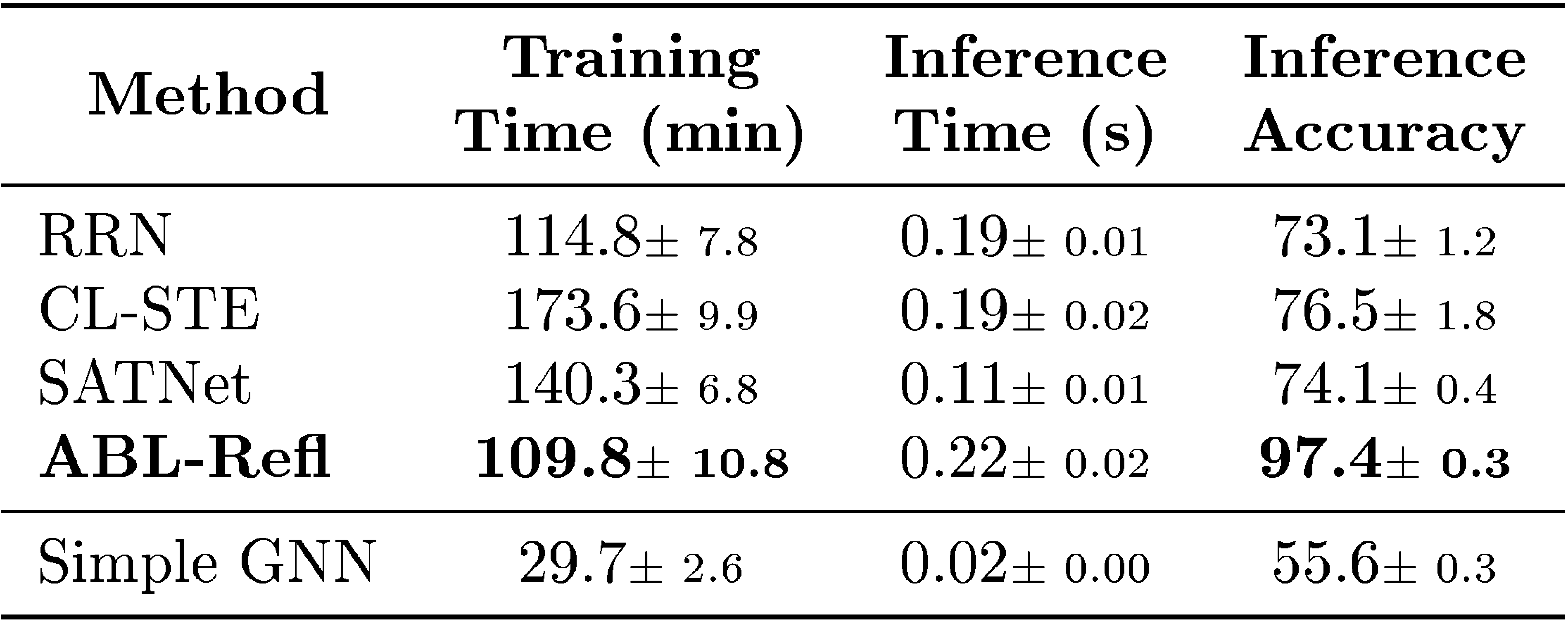

We compare ABL-Refl with the following baseline methods: 1) Recurrent Relational Network (RRN) [33], a pure neural network method, 2) CL-STE [6], a representative method of logic-based regularized loss, and 3) SATNet [7]. A detailed description of these methods is provided in Appendix A. We also report the result for Simple GNN, which is the very same neural network used in our setting, yet directly treats the intuitive output y^\hat{\boldsymbol{y}}y^ as the final output.

We report the training time (for a total of 100 epochs using 20K training data), inference time (on 1K test data) and accuracy (the percentage of completely accurate Sudoku solution boards on test data) in Table 1. We may see that our method outperforms the baselines significantly, improving by over 20% while maintaining a comparable inference time. This suggests an answer to Q1: ABL-Refl can achieve better reasoning performance. This improvement is primarily due to the use of abduction to rectify the neural network's output during inference.

Furthermore, our method reaches high accuracy in only a few epochs (training curve is shown in Appendix B), significantly reducing training time. Even considering under identical training epochs, our total training time is less than baseline methods, despite involving a time-consuming symbolic solver. This partly stems from the neural network in our approach being less complex than those in baseline methods while achieving high accuracy. Overall, this suggests an answer to Q2: ABL-Refl can reduce the training time required.

We also attempt to reduce the amount of labeled data, removing labels from 50%, 75%, and 90% of the training data. We record the inference accuracy in Table 2. It can be observed that even with only 2K labeled training data, our method still achieves far better accuracy than the baseline methods with 20K labeled training data. This suggests an answer to Q2 from another aspect: ABL-Refl can reduce the labeled training data required.

Table 2: Inference accuracy on solving Sudoku after reducing the amount of labeled data.

Comparing to Symbolic Solvers.

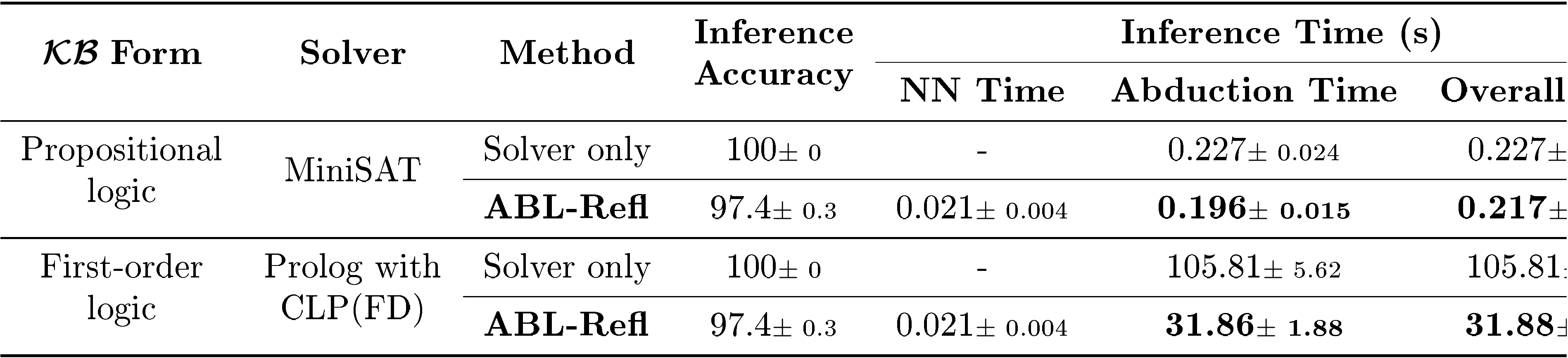

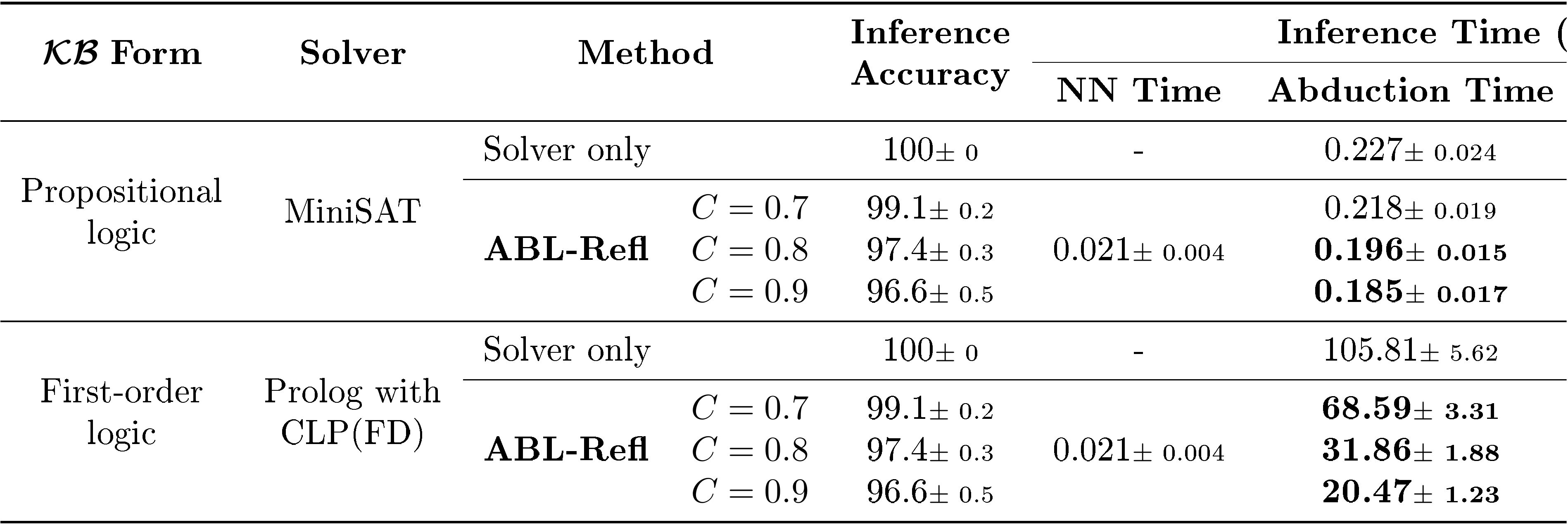

We next compare our method with merely employing symbolic solvers from scratch, to demonstrate its capability in accelerating symbolic reasoning. We perform inference on 1K test data and record the accuracy and time in Table 3. The inference time for our method includes the combined duration for data processing through both the neural network (NN time) and symbolic reasoning (abduction time).

As observed in the former two lines, our method achieves a notable acceleration in the abduction process, consequently decreasing the overall inference time, with only a minor compromise in accuracy. This efficiency gain is due to the fact that in ABL-Refl, after quickly generating an intuition through the neural network, abduction only needs to focus on areas identified as necessary by the reflection vector, whereas using only symbolic solvers requires abduction to reason through all blanks in a Sudoku puzzle. Overall, this suggests an answer to Q3: ABL-Refl can quickly generate the reflection, thereby reducing the symbolic reasoning search space and enhancing reasoning efficiency.

We also compared with Prolog with CLP(FD) [34] solver, by expressing the same KB\mathcal{KB}KB with a first-order constraint logic program. As shown in the table, we observe a significant reduction in abduction time and overall inference time, which puts another evidence to our previous answer to Q3, and also suggests an answer to Q4: ABL-Refl can effectively utilize the two most commonly used forms in symbolic knowledge representation, propositional logic and first-order logic.

4.2 Solving Visual Sudoku

Dataset and Setting.

In this section, we modify the input from 81 symbolic digits to 81 MNIST images (handwritten digits of 0-9). We use the dataset provided in SATNet [7] and use 9K Sudoku boards for training and 1K for testing.

In order to process image data, we first pass each image through a LeNet convolutional neural network (CNN) [35] to obtain the probability of each digit. The rest of our setting follows from that described in Section 4.1.

Compared Methods and Results.

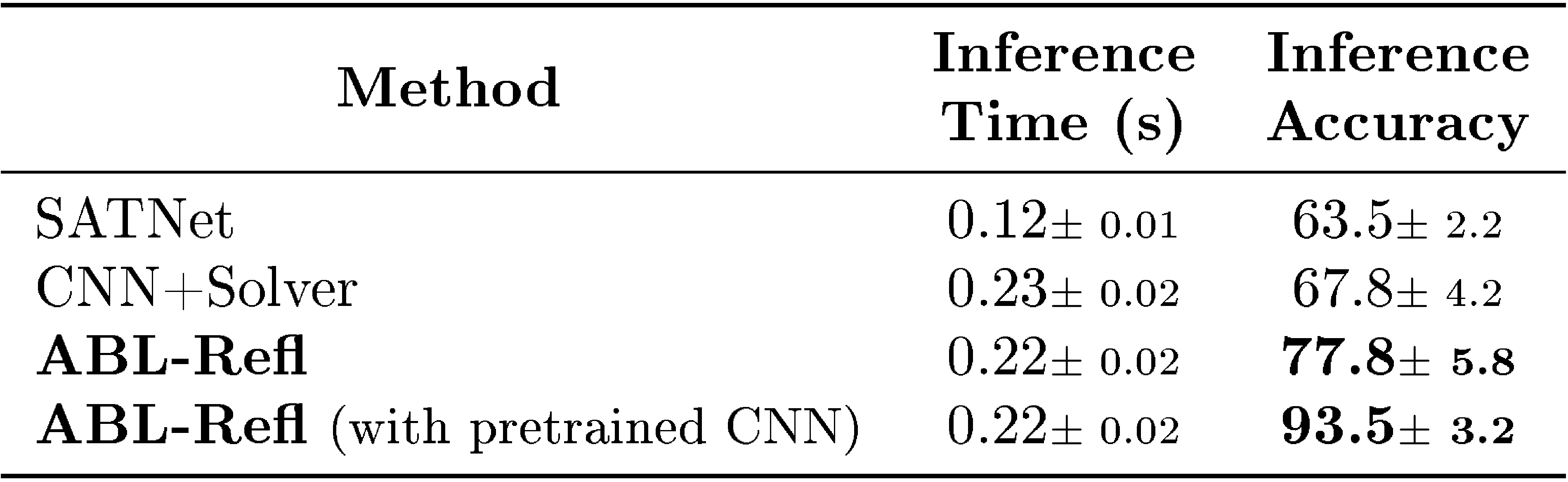

We compare ABL-Refl with SATNet, as both methods allow for end-to-end training from visual inputs. We report the results in Table 4 and the training curve in Appendix B. Compared to SATNet, ABL-Refl shows notable improvement in reasoning accuracy within only a few training epochs. We then consider pretraining the CNN in advance using self-supervised learning methods [36] and find that this can further improve accuracy. Overall, the results further suggest positive answers to Q1 and Q2.

We also compare with CNN+Solver: each image is first mapped to symbolic form by a fully trained CNN (with 99.6% accuracy on the MNIST dataset) and then directly fed into the symbolic solver to fill in the blanks and derive the final output. In such scenarios, the problem space for the symbolic solver includes all the Sudoku blanks, and additionally, since the symbolic solver cannot revise errors from CNN, any inaccuracies in CNN's output could lead the symbolic solver to crash (i.e., output no solution). Consequently, inference accuracy and time are adversely affected. This confirms the positive answer to Q3.

Finally, an overview of Section 4.1 and Section 4.2 also suggests an answer to Q4: ABL-Refl is capable of handling both symbolic and sub-symbolic forms of input data.

4.3 Solving Combinatorial Optimization Problems on Graphs

In this section, we will further expand the application domain of our method. We apply ABL-Refl to solving combinatorial optimization problems on graphs. We conduct the experiment on finding the maximum clique in this section, and provide an additional experiment in Appendix E.

Dataset and Setting.

In this task, we are given a graph G=(V,E)G=(V, E)G=(V,E) with ∣V∣=n|V|=n∣V∣=n nodes, and aim to output y∈{0,1}n\boldsymbol{y}\in\{0, 1\}^ny∈{0,1}n, where each index corresponds to a node, and the set of indices assigned the value of 1 collectively constitute the maximum clique. Note that this problem is a challenging NP-hard problem with extensive applications in real-life scenarios, and is generally considered challenging for neural networks [37].

We use several datasets from the TUDatasets [38], with their basic information shown in Table 5. We use 80% of the data for training and 20% for testing.

In our method, the body layer f1f_1f1 consists of a single GAT layer [39] and 16 gated graph convolution layers [40], and the output layer f2f_2f2 and reflection layer RRR are both linear layers. We use binary cross-entropy loss as LlabeledL_{labeled}Llabeled. The domain knowledge base KB\mathcal{KB}KB expresses the mathematical definition of maximum clique, i.e., every pair of vertices in the output set should be connected by an edge. We use Gurobi solver, an efficient mixed-integer program solver, to perform abduction. We define the consistency measurement as follows: one point is awarded for each pair of vertices if they are not connected by an edge; additionally, the size of the output set multiplied by 10 is added if the output set is indeed a clique.

Compared Methods and Results.

We compare our methods with the following baselines: 1) Erdos [41], 2) Neural SFE [42], both leading methods for solving graph combinatorial problems. Their detailed descriptions are provided in Appendix A.

We report the approximation ratios in Table 5. The approximation ratio, indicating the result set size relative to the actual maximum set size, is better when closer to 1. We may observe that our method outperforms the baseline methods, achieving near-perfect results on all datasets. This confirms the positive answer to Q1. Also, as the scale of the data increases, our method maintains a high level of accuracy, showing a more pronounced improvement compared to baseline methods. This suggests an answer to Q4: ABL-Refl is capable of handling scalable data scenarios, even in high-dimensional settings that are challenging for previous methods. Finally, an overview of this section provides another aspect to Q4: ABL-Refl can utilize a wide range of KB\mathcal{KB}KB, not limited to logical expressions but can also operate effectively with just the basic mathematical formulations.

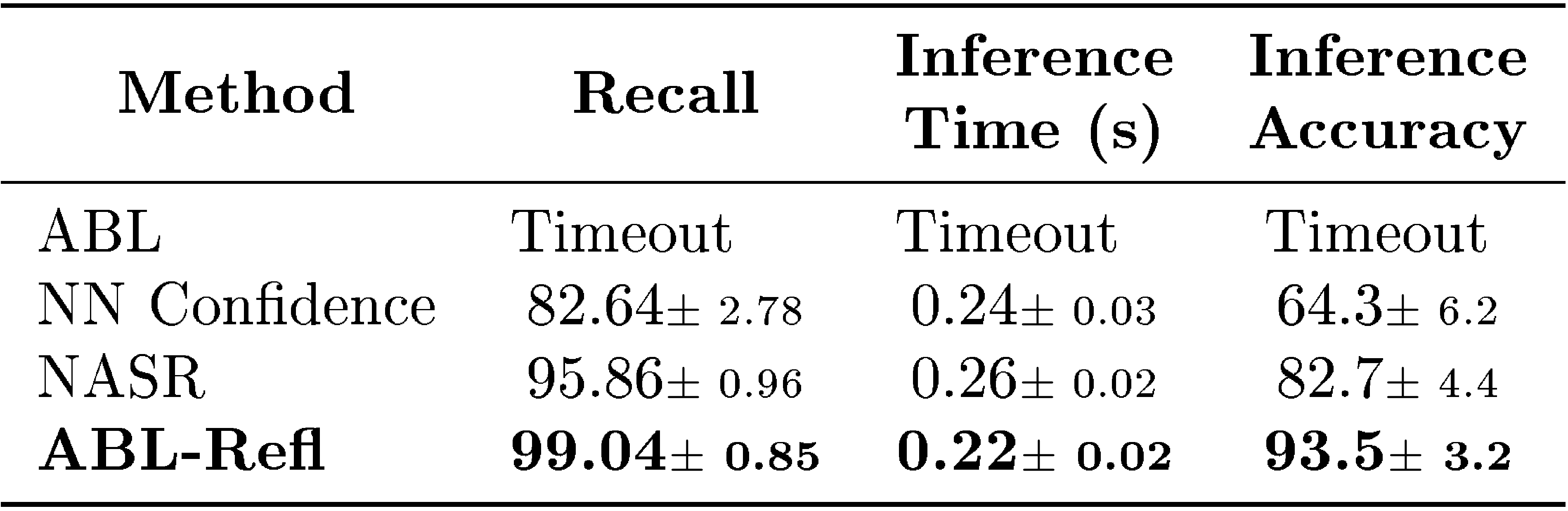

5 Effects of Reflection Mechanism

In this section, the effectiveness of ABL-Refl's reflection mechanism is validated by comparing it against alternative methods that achieve similar error detection and rectification pipelines. The reflection vector, abduced from domain knowledge, serves as an efficient attention mechanism directing symbolic search to potential error locations in neural network outputs. Three baseline approaches are tested on visual Sudoku: ABL (using consistency optimization), NN Confidence (retaining top 80% confidence outputs), and NASR (using a Transformer-based selection module trained on synthetic data). ABL suffers from computational intractability, requiring billions of queries and hours of inference time due to its exponential search space. NN Confidence performs poorly because neural networks trained without explicit knowledge integration fail to align confidence levels with domain knowledge consistency. NASR underperforms because its independently trained selection module lacks deep connection to raw data and adds sequential overhead. In contrast, ABL-Refl achieves superior recall, inference time, and accuracy by generating reflections concurrently with neural outputs and leveraging information directly from the network's body block.

This section provides a further analysis on the reflection mechanism. In ABL-Refl, the reflection is abduced from domain knowledge, and acts as an efficient attention mechanism to direct the focus for symbolic search. This reflection is the key in our method to accomplish the NeSy reasoning rectification pipeline, i.e., a pipeline that detects errors in neural networks and then invokes symbolic reasoning to rectify these positions. To corroborate the effectiveness of the reflection, we conduct direct comparison with other methods that achieve the same pipeline:

-

- ABL, minimizing the inconsistency of intuitive output and knowledge base with an external zeroth-order consistency optimization module, as detailed in Section 3.2;

-

- NN Confidence, retaining intuitive output with the top 80% confidence from the neural network result (other retain thresholds are explored in Appendix D) and passing the remaining into symbolic reasoning;

-

- NASR [27], using a Transformer-based external selection module to detect error, and the module is trained on a large synthetic dataset in advance.

We compare them on the solving visual Sudoku task in Section 4.2. For a fair comparison, all methods employ the same neural network, KB\mathcal{KB}KB and MiniSAT solver setup. We report the recall (the percentage of errors from neural networks that can be identified), inference time and accuracy (on 1K test data) in Table 6. Note that "recall" directly evaluates the effectiveness of the detection module itself. The following analysis examines the results:

- The consistency optimization in ABL faces significant efficiency challenges due to the large data scale (output dimension n=81n=81n=81). In such scenarios, the potential rectifications can reach up to 2812^{81}281, resulting in an overwhelmingly large search space for consistency optimization. Also, as an external module, its only way of interacting with KB\mathcal{KB}KB is to treat it as a black box and repetitively submit queries for consistency evaluation. As a result, it may require more than 10910^9109 queries to identify errors for each Sudoku example, resulting in several hours to complete inference on 1K test data.

- NN Confidence performs poorly in identifying outputs with errors. Since the pure data-driven neural network training does not explicitly incorporate KB\mathcal{KB}KB information, a low confidence from it does not necessarily indicate an inconsistency with the domain knowledge. This subsequently results in the frequent crashing in symbolic solver, therefore hampering the overall inference time and accuracy. This result parallels human cognitive reflection abilities, which do not show much positive correlation with System 1 intuition [43]. To further illustrate this point, we provide additional analysis, including a case study, in Appendix D.

- Our method also outperforms NASR, and notably, without the need of a synthetic dataset. This could be due to the fact that NASR's error-selection module is trained independently from other components, and operates sequentially and separately during inference. Therefore, it can only rely on information from the output label, in contrast to our method, which can leverage information directly from the body block of neural network, establishing a deeper connection with the raw data. Additionally, in NASR, traversing the separate selection module takes additional time, whereas in ABL-Refl, the reflection is generated concurrently with the neural network output, avoiding efficiency loss.

6 Conclusion

In this section, the authors present Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl), a neuro-symbolic method that addresses the challenge of combining neural network learning with logical reasoning. The approach leverages domain knowledge to generate a reflection vector that identifies potential errors in neural network outputs, then uses this vector as an attention mechanism to guide symbolic reasoning toward a focused problem space rather than searching exhaustively. Through experiments on tasks including Sudoku solving and graph combinatorial optimization, ABL-Refl demonstrates significant performance advantages over existing neuro-symbolic methods, achieving superior reasoning accuracy while requiring fewer training resources and maintaining faster inference speed. The method's ability to preserve both the learning capabilities of neural networks and the precision of logical reasoning, coupled with its versatility across different problem domains, positions it as a promising approach for broader applications, particularly in enhancing the trustworthiness and reliability of large language models by detecting and correcting errors in their outputs.

In this paper, we present Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl). It leverages domain knowledge to abduce a reflection vector, which flags potential errors in neural network outputs and then invokes abduction, serving as an attention mechanism for symbolic reasoning to focus on a much smaller problem space. Experiments show that ABL-Refl significantly outperforms other NeSy methods, achieving excellent reasoning accuracy with fewer training resources, and has successfully enhanced reasoning efficiency.

ABL-Refl preserves the integrity of both machine learning and logical reasoning with superior inference speed and high versatility. Therefore, it has the potential for broad application. In the future, it can be applied to large language models [44] to help identify errors within their outputs, and subsequently exploit symbolic reasoning to enhance their trustworthiness and reliability.

Acknowledgments

In this section, the authors acknowledge the funding sources that supported their research on Abductive Reflection (ABL-Refl). The work was financially backed by two grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC), specifically grants numbered 62176117 and 62206124, along with support from the Jiangsu Science Foundation Leading-edge Technology Program under grant BK20232003. These funding bodies provided the necessary resources to develop and validate the ABL-Refl framework, which integrates neural networks with symbolic reasoning through an abductive reflection mechanism. The acknowledgment highlights the collaborative nature of advancing neuro-symbolic AI research and underscores the importance of institutional support in enabling innovative approaches to combine machine learning with logical reasoning for enhanced accuracy, efficiency, and reduced training requirements.

This research was supported by the NSFC (62176117, 62206124) and Jiangsu Science Foundation Leading-edge Technology Program (BK20232003).

A Comparison Methods

In this section, the baseline methods used for comparison across different experimental tasks are detailed to contextualize the performance evaluation of ABL-Refl. For Sudoku experiments, the baselines include Recurrent Relational Network (RRN), a pure neural network approach; CL-STE, which injects logical knowledge as neural network constraints during training; and SATNet, which incorporates a differentiable MaxSAT solver into the neural architecture. CL-STE represents logic-based regularized loss methods and achieves strong accuracy and efficiency by avoiding complex SDD construction, while other methods like ABL struggle with exponential search spaces leading to runtime thousands of times longer, and DeepProbLog and NeurASP face substantial computational costs or accuracy limitations. For combinatorial optimization on graphs, the baselines are Erdos, which uses neural networks to parametrize distributions over sets, and Neural SFE, which extends set functions to continuous domains, both employing the same graph neural network body block as ABL-Refl for fair comparison.

In this section, we will provide a brief supplementary introduction to the compared baseline methods used in experiments.

A.1 Solving Sudoku

In the solving Sudoku experiment (Section 4.1 and Section 4.2), we have compared our method with the following baselines:

-

- Recurrent Relational Network (RRN) [33], a state-of-the-art pure neural network method tailored for this problem;

-

- CL-STE [6], injecting logical knowledge (defined in the same way as our KB\mathcal{KB}KB) as neural network constraints during the training of RRN;

-

- SATNet [7], incorporating a differentiable MaxSAT solver into the neural network to perform reasoning.

Note that CL-STE is a representative method of logic-based regularized loss, relaxing symbolic logic as neural network loss. Additionally, among these methods, CL-STE stands out in both accuracy and efficiency (partly because it prevents constructing complex SDDs, unlike other methods including semantic loss [5]).

Other lines of methods generally underperform above baselines in scenarios where nnn (the scale of y\boldsymbol{y}y) is high. For instance, ABL faces the challenge where consistency optimization needs to choose among exponential query candidates, resulting in runtimes thousands of times longer than other methods, as seen in Section 5. Take two other representative NeSy methods as examples: DeepProbLog [17] involves substantial computational costs, taking days to complete solving Sudoku; NeurASP [18] also performs slow and lags in accuracy, as shown in Yang et al. [6].

A.2 Solving Combinatorial Optimization on Graphs

In the solving combinatorial optimization on graphs experiment (Section 4.3 and Appendix E), we have compared our method with the following baselines:

-

- Erdos [41], optimizing set functions using a neural network parametrizing a distribution over sets;

-

- Neural SFE [42], optimizing set functions by extending them onto high-dimensional continuous domains.

In this experiment, the above methods use the same body block graph neural network as our method.

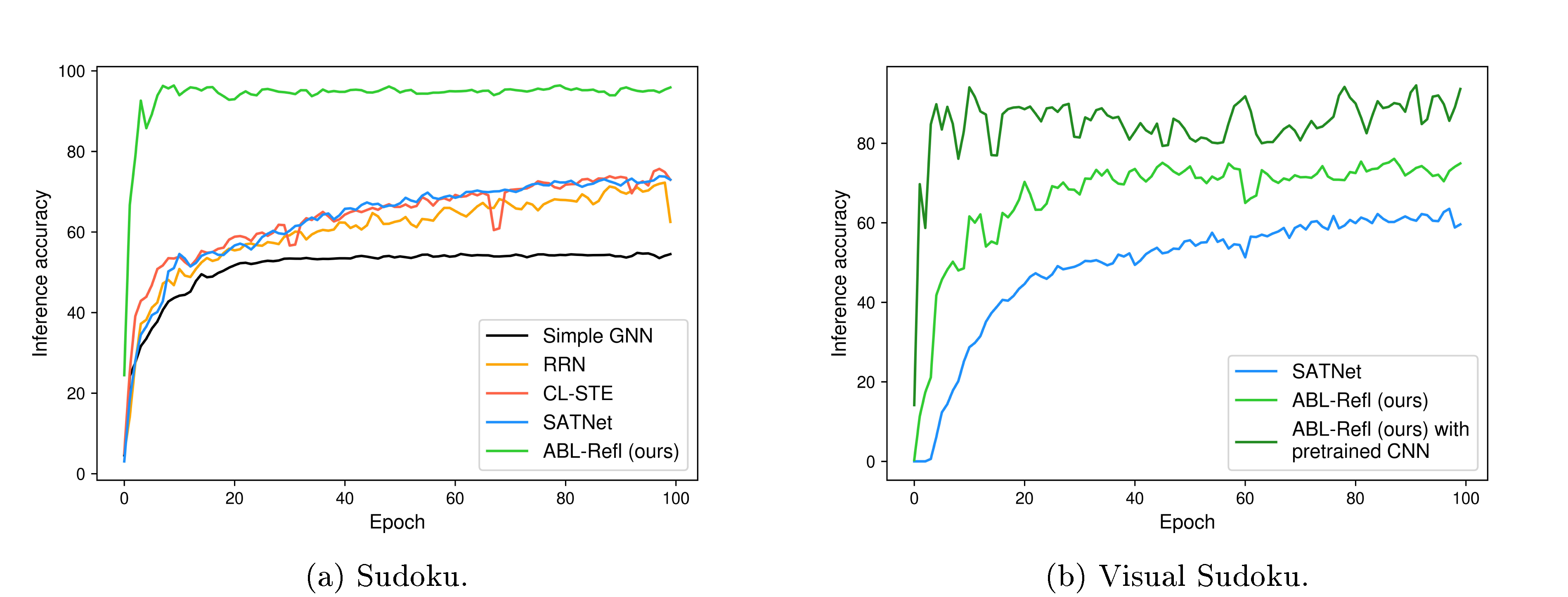

B Training Curve

In this section, the training efficiency of ABL-Refl is demonstrated through training curves for both symbolic Sudoku and visual Sudoku experiments. Figure 4 presents two plots with training epochs on the horizontal axis and inference accuracy on the vertical axis, comparing ABL-Refl against baseline methods including RRN, CL-STE, and SATNet. The key finding is that ABL-Refl achieves high accuracy within just a few training epochs, substantially reducing the time required to reach strong performance compared to other methods. This rapid convergence suggests that the reflection mechanism effectively guides the learning process by focusing symbolic reasoning on likely error positions, allowing the model to learn more efficiently from fewer training iterations. The accelerated training characteristic reinforces ABL-Refl's practical advantage, making it not only more accurate but also significantly faster to train than competing neuro-symbolic approaches.

In this section, we will report the training curve in the experiments on solving Sudoku (Section 4.1) and visual Sudoku (Section 4.2). The respective training curves for each scenario are shown in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, with the horizontal axis representing training epochs and the vertical axis representing inference accuracy. We may see that our method achieves high accuracy within just a few epochs, significantly reducing training time compared to other baseline methods.

C Discussion on Hyperparameter CCC

In this section, we will discuss the effect of the hyperparameter CCC. Previous experiments in Section 4 and Section 5, CCC was consistently set to 0.8, and we will now explore adjustments. We report the extended results in Table 7 and Table 8. It is shown that when CCC is set within a wide range, ABL-Refl uniformly outperforms the baseline methods.

Intuitively, as mentioned in Section Figure 3, setting CCC lower delegates more elements to the solver for correction, thereby often enhancing reasoning accuracy. The results in Table 7 and Table 8 have also demonstrated this point.

However, setting CCC to more extreme lower values, while potentially further enhancing reasoning accuracy, will face the risk of weakening the reflection in accelerating reasoning, since more elements are delegated to symbolic reasoning. Therefore, we do not recommend excessively lowering CCC. For this effect of CCC in computational efficiency, we have also conducted experimental evaluation: The runtime after adjusting CCC are reported in Table 9. It can be seen that setting CCC to a higher value can further narrow the search space for symbolic reasoning, thereby offering a more substantial efficiency improvement. (On the contrary, setting CCC to a more extreme high value would essentially rely merely on the neural network's intuitive output, rendering the reflection vector ineffective; hence, such settings are not considered.)

In summary, to utilize the reflection vector’s role in bridging neural network outputs and symbolic reasoning, setting CCC within a moderate range is advised. Experimental evidence suggests that within this broad range, e.g., 0.6-0.9, the specific value of CCC actually does not significantly impact outcomes; it is merely a balance between accuracy and computation time.

D More Discussion on Comparison with Neural Network Confidence

In this section, the core idea of ABL-Refl—identifying neural network outputs inconsistent with domain knowledge—is contrasted with the naive approach of using the network's own confidence scores to flag errors. A case study from Sudoku demonstrates that while the reflection vector correctly identifies positions violating knowledge-base constraints (duplicate numbers in rows, columns, or subgrids), neural network confidence misidentifies errors based on spurious data patterns learned during training, such as common co-occurrences unrelated to logical rules. Because pure data-driven networks lack explicit access to symbolic knowledge during training, their confidence values fail to correlate with knowledge-base compatibility. Extended experiments across multiple retention thresholds (60%, 70%, 80%, 90%) show ABL-Refl consistently outperforms the NN Confidence baseline in both recall and inference accuracy, achieving over 98% recall and above 91% accuracy regardless of threshold, while NN Confidence struggles with recall dropping from 93% to 71% and accuracy plummeting from 77% to 52% as thresholds increase.

The core idea of ABL-Refl is to identify areas in the neural network’s intuitive output where inconsistencies with knowledge are most likely to occur. Thus, a straightforward approach might seem to be letting the neural network itself highlight errors, i.e., treating elements with low confidence values from the neural network result as potential errors. However, Section 5 have proven that such a naive approach significantly underperforms our method. This is because neural networks cannot explicitly utilize symbolic knowledge during training, making it challenging to establish a correlation between confidence levels and inconsistencies with knowledge.

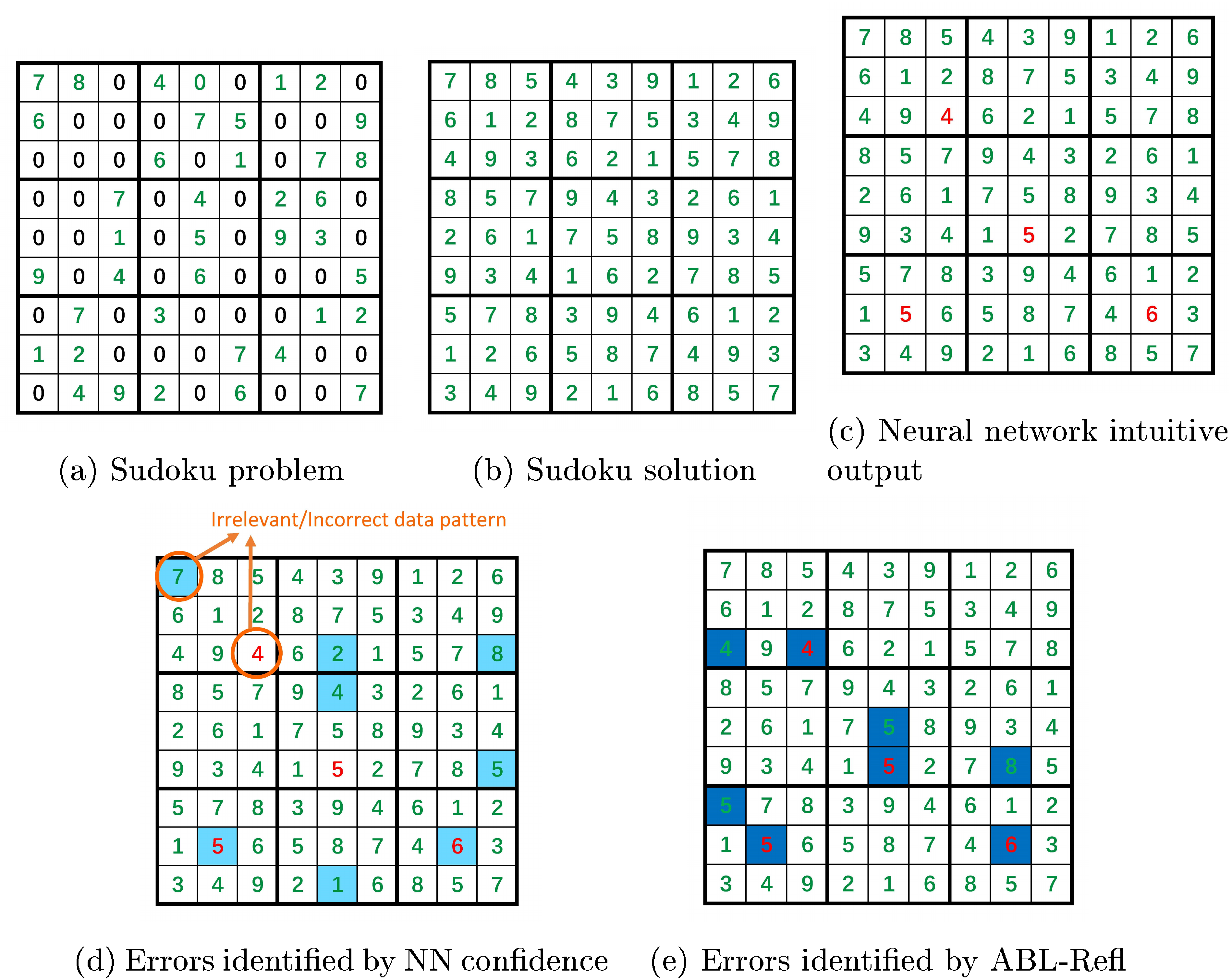

To illustrate this more clearly, we now demonstrate a case study in the solving Sudoku experiment: Figures 5a-5b below depict a Sudoku problem and its correct solution. Figure 5c shows the intuitive output obtained from the GNN, where several numbers marked in red are incorrect. Figure 5d and Figure 5e display the results using NN confidence and the reflection vector, respectively, with identified potential error positions in blue.

It can be seen that the errors marked by the reflection vector generally correspond to the constraints in KB\mathcal{KB}KB, containing duplicate numbers either in a row, column, or subgrid. In contrast, errors identified by NN confidence are difficult to align with such knowledge. Take the incorrect identification of the first row, first column as an example, after examining the dataset, we find that there are some of the Sudoku solutions with a number 4" in the third row, third column and a number 7" in the first row, first column at the same time. These irrelevant yet common data patterns likely lead the neural network to erroneously learn during training. Hence, when an error occurs in the third row and third column, the confidence in the first row and first column also drops. This case study highlights that pure data-driven networks cannot explicitly utilize KB knowledge: during training, they only have access to data labels, not the logical principles behind the data. Consequently, due to factors like learning incorrect data patterns or overfitting to noise, confidence values often misalign with the compatibility with domain knowledge, leading them become unreliable to identify errors. In contrast, the training information for the reflection vector is directly derived from the KB\mathcal{KB}KB.

Furthermore, as discussed in Appendix C, in ABL-Refl, adjusting the hyperparameter CCC, as a soft margin, can help determine how much of the neural network's output is retained. In Section 5, corresponding to C=0.8C=0.8C=0.8, the neural network's output with top 80% confidence was retained. We will now test adjusting this threshold of retaining neural network's output. We report the results in Table 10. As can be seen, regardless of the threshold value, our method consistently outperforms NN confidence.

E Additional Experiment on Solving Combinatorial Optimization Problems on Graphs

In this section, the authors extend their ABL-Refl method to the problem of finding maximum independent sets in graphs, demonstrating the approach's flexibility across different reasoning scenarios. While the previous maximum clique experiment relied on high homophily (nodes clustering together), the independent set problem exhibits significant heterophily (nodes being separated), which typically challenges graph neural networks. Using the same graph neural network structure and Gurobi solver with minimal modifications to the knowledge base and consistency measurement, ABL-Refl achieves near-perfect approximation ratios across four datasets (ENZYMES, PROTEINS, IMDB-Binary, COLLAB) with performance around 0.94-0.99 depending on the hyperparameter C. Notably, while baseline methods (Erdos and Neural SFE) show degraded performance when switching from maximum clique to maximum independent set tasks, ABL-Refl maintains consistently high performance, highlighting its robustness in handling fundamentally different reasoning requirements with only minimal adjustments to the reasoning components.

In this section, we present an additional experiment on solving combinatorial optimization problems on graphs, finding the maximum independent set. In this experiment, we will demonstrate how our method can easily extend across varied reasoning scenarios.

Dataset and Settings.

The input is the same as in Section 4.3 for solving the maximum clique, given a graph G=(V,E)G=(V, E)G=(V,E) with ∣V∣=n|V|=n∣V∣=n nodes, but in this section, we aim for the output y∈{0,1}n\boldsymbol{y}\in\{0, 1\}^ny∈{0,1}n where the set of value 1 collectively constitutes the maximum independent set. While the two problems share similarities, they exhibit distinct reasoning capabilities: cliques rely on high homophily, whereas an independent set demonstrates significant heterophily. Generally, it is challenging for graph neural networks to simultaneously handle both scenarios effectively.

We utilize the same structure of graph neural networks as in Section 4.3. For the reasoning part, we continue to use Gurobi as the symbolic solver, and KB\mathcal{KB}KB remains the basic mathematical definition of an independent set, i.e., no two nodes are connected by an edge. For consistency measurement, we adopt a similar definition in Section 4.3 as follows: one point is awarded for each pair of vertices if they are not connected by an edge; additionally, if the output set is indeed an independent set, the size of the output set multiplied by 10 is added. We may see that although the nature of the reasoning becomes entirely opposite compared to solving the maximum clique, we are able to flexibly transition to the new scenario with minimal changes.

Results.

We report the results in Table 11. We may see that our method significantly outperforms compared methods. Additionally, when compared to the results in Table 8, it can be observed that the performance of other baselines has declined when switching from finding maximum cliques to this task of finding maximum independent set. However, the performance of ABL-Refl has remained near perfect.

References

In this section, the references catalogue foundational and contemporary work spanning cognitive science, neuro-symbolic AI, and combinatorial optimization. The bibliography begins with psychological studies on dual-process cognition distinguishing intuitive System 1 from reflective System 2 thinking, then transitions to neuro-symbolic approaches that integrate neural learning with logical reasoning through methods like semantic loss functions, differentiable SAT solvers, and abductive learning frameworks. Key contributions include techniques for embedding symbolic constraints into neural networks, toolkits for implementing abductive learning, and applications ranging from Sudoku solving to judicial sentencing and historical document analysis. The references further cover graph neural networks for combinatorial problems like maximum clique and independent set finding, alongside datasets and benchmarks for evaluating AI reasoning capabilities. Together, these works establish the theoretical foundation and practical infrastructure for bridging fast neural intuition with deliberate symbolic reasoning.

[1] Frederick, S. 2005. Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic perspectives, 19(4): 25–42.

[2] Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. macmillan.

[3] Bengio, Y. 2019. From system 1 deep learning to system 2 deep learning. In Neural Information Processing Systems.

[4] Hitzler, P. 2022. Neuro-symbolic artificial intelligence: The state of the art. IOS Press.

[5] Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Friedman, T.; Liang, Y.; and Broeck, G. 2018. A semantic loss function for deep learning with symbolic knowledge. In International conference on machine learning, 5502–5511. PMLR.

[6] Yang, Z.; Lee, J.; and Park, C. 2022. Injecting logical constraints into neural networks via straight-through estimators. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 25096–25122. PMLR.

[7] Wang, P.-W.; Donti, P.; Wilder, B.; and Kolter, Z. 2019. Satnet: Bridging deep learning and logical reasoning using a differentiable satisfiability solver. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 6545–6554. PMLR.

[8] Zhou, Z.-H. 2019. Abductive learning: towards bridging machine learning and logical reasoning. Science China Information Sciences, 62: 1–3.

[9] Zhou, Z.-H.; and Huang, Y.-X. 2022. Abductive Learning. In Hitzler, P.; and Sarker, M. K., eds., Neuro-Symbolic Artificial Intelligence: The State of the Art, 353–369. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

[10] Sinayev, A.; and Peters, E. 2015. Cognitive reflection vs. calculation in decision making. Frontiers in psychology, 6: 532.

[11] Serafini, L.; and Garcez, A. d. 2016. Logic tensor networks: Deep learning and logical reasoning from data and knowledge. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.04422.

[12] Marra, G.; Giannini, F.; Diligenti, M.; and Gori, M. 2020. Integrating learning and reasoning with deep logic models. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, 517–532. Springer.

[13] Hoernle, N.; Karampatsis, R. M.; Belle, V.; and Gal, K. 2022. Multiplexnet: Towards fully satisfied logical constraints in neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 36, 5700–5709.

[14] Ahmed, K.; Wang, E.; Chang, K.-W.; and Van den Broeck, G. 2022. Neuro-symbolic entropy regularization. In Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, 43–53. PMLR.

[15] Amos, B.; and Kolter, J. Z. 2017. Optnet: Differentiable optimization as a layer in neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 136–145. PMLR.

[16] Selsam, D.; Lamm, M.; Bünz, B.; Liang, P.; de Moura, L.; and Dill, D. L. 2018. Learning a SAT solver from single-bit supervision. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.03685.

[17] Manhaeve, R.; Dumancic, S.; Kimmig, A.; Demeester, T.; and De Raedt, L. 2018. Deepproblog: Neural probabilistic logic programming. advances in neural information processing systems, 31.

[18] Yang, Z.; Ishay, A.; and Lee, J. 2020. Neurasp: Embracing neural networks into answer set programming. In 29th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

[19] Huang, Y.-X.; Hu, W.-C.; Gao, E.-H.; and Jiang, Y. 2024. ABLkit: A Python Toolkit for Abductive Learning. Frontiers of Computer Science, pp. to appear.

[20] Huang, Y.-X.; Dai, W.-Z.; Yang, J.; Cai, L.-W.; Cheng, S.; Huang, R.; Li, Y.-F.; and Zhou, Z.-H. 2020. Semi-Supervised Abductive Learning and Its Application to Theft Judicial Sentencing. In Proceedings of the 20th IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM'20), 1070–1075.

[21] Cai, L.-W.; Dai, W.-Z.; Huang, Y.-X.; Li, Y.-F.; Muggleton, S. H.; and Jiang, Y. 2021. Abductive Learning with Ground Knowledge Base. In Proceedings of the 30th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI'21), 1815–1821.

[22] Wang, J.; Deng, D.; Xie, X.; Shu, X.; Huang, Y.-X.; Cai, L.-W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.-L.; Zhou, Z.-H.; and Wu, Y. 2021. Tac-Valuer: Knowledge-based Stroke Evaluation in Table Tennis. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD'21), 3688–3696.

[23] Gao, E.-H.; Huang, Y.-X.; Hu, W.-C.; Zhu, X.-H.; and Dai, W.-Z. 2024. Knowledge-Enhanced Historical Document Segmentation and Recognition. In Proceedings of the 38th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI'24), 8409–8416.

[24] Nair, V.; Bartunov, S.; Gimeno, F.; Von Glehn, I.; Lichocki, P.; Lobov, I.; O'Donoghue, B.; Sonnerat, N.; Tjandraatmadja, C.; Wang, P.; et al. 2020. Solving mixed integer programs using neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.13349.

[25] Nye, M.; Tessler, M.; Tenenbaum, J.; and Lake, B. M. 2021. Improving coherence and consistency in neural sequence models with dual-system, neuro-symbolic reasoning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34: 25192–25204.

[26] Han, Q.; Yang, L.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, A.; Sun, R.; and Luo, X. 2023. A GNN-Guided Predict-and-Search Framework for Mixed-Integer Linear Programming. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.05636.

[27] Cornelio, C.; Stuehmer, J.; Hu, S. X.; and Hospedales, T. 2023. Learning where and when to reason in neuro-symbolic inference. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations.

[28] Dai, W.-Z.; Xu, Q.; Yu, Y.; and Zhou, Z.-H. 2019. Bridging machine learning and logical reasoning by abductive learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 32.

[29] Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Li, G.; Cai, S.; Xiong, Y.; and Zhang, L. 2020. NLocalSAT: Boosting local search with solution prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.09398.

[30] Williams, R. J. 1992. Simple statistical gradient-following algorithms for connectionist reinforcement learning. Reinforcement learning, 5–32.

[32] Sörensson, N. 2010. Minisat 2.2 and minisat++ 1.1. A short description in SAT Race.

[33] Palm, R.; Paquet, U.; and Winther, O. 2018. Recurrent relational networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 31.

[34] Triska, M. 2012. The finite domain constraint solver of SWI-Prolog. In Functional and Logic Programming: 11th International Symposium, 307–316. Springer.

[35] LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; and Haffner, P. 1998. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE, 86(11): 2278–2324.

[36] Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; and Hinton, G. 2020. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International conference on machine learning, 1597–1607. PMLR.

[37] Zhang, B.; Luo, S.; Wang, L.; and He, D. 2023. Rethinking the expressive power of gnns via graph biconnectivity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.09505.

[38] Morris, C.; Kriege, N. M.; Bause, F.; Kersting, K.; Mutzel, P.; and Neumann, M. 2020. Tudataset: A collection of benchmark datasets for learning with graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.08663.

[39] Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; and Bengio, Y. 2017. Graph attention networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.10903.

[40] Li, Y.; Tarlow, D.; Brockschmidt, M.; and Zemel, R. 2015. Gated graph sequence neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.05493.

[41] Karalias, N.; and Loukas, A. 2020. Erdos goes neural: an unsupervised learning framework for combinatorial optimization on graphs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33: 6659–6672.

[42] Karalias, N.; Robinson, J.; Loukas, A.; and Jegelka, S. 2022. Neural Set Function Extensions: Learning with Discrete Functions in High Dimensions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.04055.

[43] Pennycook, G.; Cheyne, J. A.; Koehler, D. J.; and Fugelsang, J. A. 2016. Is the cognitive reflection test a measure of both reflection and intuition? Behavior research methods, 48: 341–348.

[44] Mialon, G.; Fourrier, C.; Swift, C.; Wolf, T.; LeCun, Y.; and Scialom, T. 2023. GAIA: a benchmark for General AI Assistants. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.12983.