Block Diffusion: Interpolating Between Autoregressive and Diffusion Language Models

Show me an executive summary.

Purpose and Context

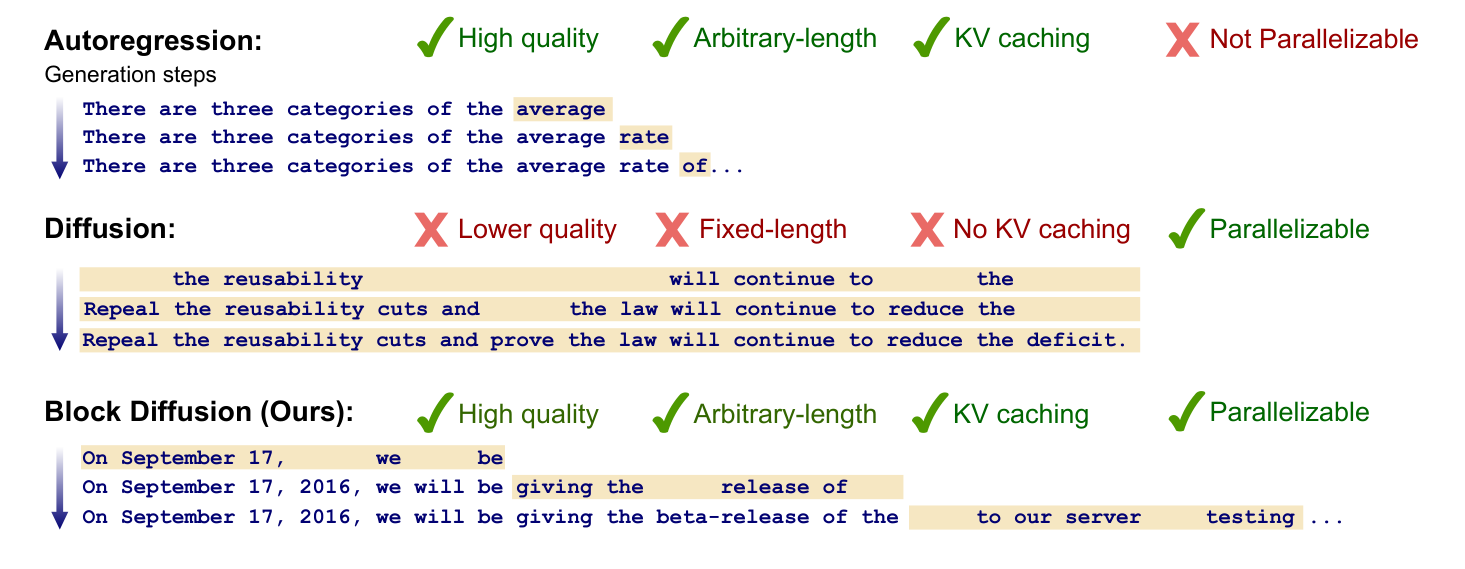

Language models today use either autoregressive generation (producing one token at a time in sequence) or diffusion methods (gradually denoising all tokens in parallel). Autoregressive models generate high-quality text but slowly, requiring hundreds of sequential steps. Diffusion models can theoretically generate faster through parallelization and offer better controllability, but they produce lower-quality text, cannot generate variable-length sequences, and lack efficiency optimizations like key-value caching. This work introduces Block Diffusion Language Models (BD3-LMs) to combine the strengths of both approaches while overcoming their individual limitations.

What Was Done

The research team developed a hybrid approach that divides text into blocks and processes them sequentially (like autoregressive models) while using diffusion within each block to generate multiple tokens in parallel. They built specialized training algorithms to make this computationally efficient, identified that high variance in gradient updates was limiting diffusion model quality, and designed custom noise schedules that reduce this variance. The models were trained and evaluated on standard language modeling benchmarks (One Billion Words dataset and OpenWebText) using 110 million parameter transformer architectures.

Key Findings

BD3-LMs achieve the best performance among all diffusion-based language models tested, with perplexity improvements of up to 13% over the previous best diffusion method. When generating sequences of length 1024 tokens, BD3-LMs produced text with a quality score of 25.7 (measured by generative perplexity under GPT2-Large), compared to 46.8 for the best previous diffusion method and 14.1 for standard autoregressive models. The models successfully generated sequences over 10 times longer than previous diffusion models (up to approximately 10,000 tokens versus 1,024 tokens) and did so using 40 times fewer computational steps than alternative block-based approaches. The custom noise schedules reduced training variance from 1.52 to 0.11 in controlled tests, directly improving final model quality.

What the Results Mean

These findings demonstrate that diffusion language models can approach autoregressive quality while maintaining advantages in parallelization and controllability. The ability to generate variable-length sequences removes a major practical limitation that prevented diffusion models from being used in applications like chat systems. The reduced number of generation steps (bounded by sequence length rather than requiring thousands of diffusion steps) makes these models more practical for real-world deployment. However, a quality gap remains—BD3-LMs still underperform autoregressive models by approximately 45% on standard metrics, meaning they are not yet ready to replace autoregressive approaches for applications requiring the highest quality text.

Recommendations and Next Steps

Organizations evaluating text generation approaches should consider BD3-LMs when controllability or parallel generation matters more than achieving absolute best quality, such as in constrained generation tasks or applications requiring real-time intervention. For production chat systems or applications requiring state-of-the-art text quality, autoregressive models remain the better choice. Researchers should explore whether the variance reduction techniques developed here can improve standard diffusion models (not just block-based versions), as this could yield broader benefits. Development teams should investigate optimal block sizes for specific applications—the experiments showed that smaller blocks (4 tokens) produced better quality than larger blocks (128 tokens), but the ideal size likely depends on the specific use case. Further work is needed to close the remaining quality gap before BD3-LMs can compete directly with autoregressive models on all fronts.

Limitations and Confidence

Training BD3-LMs costs up to twice as much computationally as training standard diffusion models, though the team reduced this overhead through algorithmic optimizations and pre-training strategies. Generation speed improvements depend on block size—smaller blocks (which perform better) reduce the parallelization benefit. The models inherit general limitations of all generative language models, including potential for generating false information, copyright concerns, and harmful content. The results are based on relatively small models (110 million parameters) and specific benchmarks; performance characteristics may differ at larger scales or on other types of text. Confidence is high that the variance reduction approach improves diffusion model quality based on controlled experiments, but confidence is moderate that these specific models will perform well on diverse real-world tasks beyond the benchmarks tested.

Authors: Marianne Arriola†^{†}†, Aaron Kerem Gokaslan, Justin T. Chiu‡^{‡}‡, Zhihan Yang†^{†}†, Zhixuan Qi†^{†}†, Jiaqi Han¶^{¶}¶, Subham Sekhar Sahoo†^{†}†, Volodymyr Kuleshov†^{†}†

†^††Cornell Tech, NY, USA. ¶^¶¶Stanford University, CA, USA.‡^‡‡ Cohere, NY, USA.

Abstract

Diffusion language models offer unique benefits over autoregressive models due to their potential for parallelized generation and controllability, yet they lag in likelihood modeling and are limited to fixed-length generation. In this work, we introduce a class of block diffusion language models that interpolate between discrete denoising diffusion and autoregressive models. Block diffusion overcomes key limitations of both approaches by supporting flexible-length generation and improving inference efficiency with KV caching and parallel token sampling. We propose a recipe for building effective block diffusion models that includes an efficient training algorithm, estimators of gradient variance, and data-driven noise schedules to minimize the variance. Block diffusion sets a new state-of-the-art performance among diffusion models on language modeling benchmarks and enables generation of arbitrary-length sequences. We provide the code, along with the model weights and blog post on the project page:

1. Introduction

In this section, the authors address three key limitations of discrete diffusion language models: their restriction to fixed-length generation, their inability to use KV caching due to bidirectional context requirements, and their inferior perplexity compared to autoregressive models. To overcome these challenges, they introduce Block Discrete Denoising Diffusion Language Models (BD3-LMs), which combine autoregressive modeling over blocks of tokens with discrete diffusion within each block. The main technical innovations include specialized training algorithms for efficient computation, estimators of gradient variance that identify high variance as a performance bottleneck, and custom data-driven noise schedules designed to minimize this variance. The resulting models achieve state-of-the-art perplexity among discrete diffusion approaches, support arbitrary-length sequence generation, enable KV caching and parallel token sampling for improved inference efficiency, and significantly outperform alternative semi-autoregressive formulations while requiring an order of magnitude fewer generation steps.

Diffusion models are widely used to generate images ([1, 2, 3]) and videos ([4, 5]), and are becoming increasingly effective at generating discrete data such as text ([6, 7]) or biological sequences ([8, 9]). Compared to autoregressive models, diffusion models have the potential to accelerate generation and improve the controllability of model outputs ([10, 11, 12, 13]).

Discrete diffusion models currently face at least three limitations. First, in applications such as chat systems, models must generate output sequences of arbitrary length (e.g., a response to a user's question). However, most recent diffusion architectures only generate fixed-length vectors ([14, 6]). Second, discrete diffusion uses bidirectional context during generation and therefore cannot reuse previous computations with KV caching, which makes inference less efficient ([15]). Third, the quality of discrete diffusion models, as measured by standard metrics such as perplexity, lags behind autoregressive approaches and further limits their applicability ([16, 7]).

This paper makes progress towards addressing these limitations by introducing Block Discrete Denoising Diffusion Language Models (BD3-LMs), which interpolate between discrete diffusion and autoregressive models. Specifically, block diffusion models (also known as semi-autoregressive models) define an autoregressive probability distribution over blocks of discrete random variables ([17, 18]); the conditional probability of a block given previous blocks is specified by a discrete denoising diffusion model ([14, 7]).

Developing effective BD3-LMs involves two challenges. First, efficiently computing the training objective for a block diffusion model is not possible using one standard forward pass of a neural network and requires developing specialized algorithms. Second, training is hampered by the high variance of the gradients of the diffusion objective, causing BD3-LMs to under-perform autoregression even with a block size of one (when both models should be equivalent). We derive estimators of gradient variance, and demonstrate that it is a key contributor to the gap in perplexity between autoregression and diffusion. We then propose custom noise processes that minimize gradient variance and make progress towards closing the perplexity gap.

We evaluate BD3-LMs on language modeling benchmarks, and demonstrate that they are able to generate sequences of arbitrary length, including lengths that exceed their training context. In addition, BD3-LMs achieve new state-of-the-art perplexities among discrete diffusion models. Compared to alternative semi-autoregressive formulations that perform Gaussian diffusion over embeddings ([19, 20]), our discrete approach features tractable likelihood estimates and yields samples with improved generative perplexity using an order of magnitude fewer generation steps. In summary, our work makes the following contributions:

- We introduce block discrete diffusion language models, which are autoregressive over blocks of tokens; conditionals over each block are based on discrete diffusion. Unlike prior diffusion models, block diffusion supports variable-length generation and KV caching.

- We introduce custom training algorithms for block diffusion models that enable efficiently leveraging the entire batch of tokens provided to the model.

- We identify gradient variance as a limiting factor of the performance of diffusion models, and we propose custom data-driven noise schedules that reduce gradient variance.

- Our results establish a new state-of-the-art perplexity for discrete diffusion and make progress toward closing the gap to autoregressive models.

2. Background: Language Modeling Paradigms

In this section, two foundational approaches to language modeling are contrasted to set the stage for block diffusion models. Autoregressive models factorize the probability of a sequence into a product of conditional probabilities for each token given all preceding tokens, enabling efficient training through next-token prediction but requiring sequential generation that scales linearly with sequence length. Discrete denoising diffusion probabilistic models take an alternative approach by reversing a forward corruption process that progressively adds noise to clean data, defining latent variables at different noise levels and modeling the reverse process using a neural network that predicts clean tokens from noisy sequences. While diffusion models are trained using variational inference with a negative evidence lower bound involving KL divergences between forward and reverse processes, they offer potential advantages in parallelization and controllability but face challenges in likelihood quality and fixed-length generation constraints that motivate the hybrid block diffusion approach introduced in subsequent sections.

Notation We consider scalar discrete random variables with VVV categories as 'one-hot' column vectors in the space V={x∈{0,1}V:∑ixi=1}⊂ΔV\mathcal{V} = \{{\mathbf x} \in \{0, 1\}^{V} : \sum_i {\mathbf x}_i = 1\}\subset \Delta^VV={x∈{0,1}V:∑ixi=1}⊂ΔV for the simplex ΔV\Delta^VΔV. Let the VVV-th category denote a special [MASK] token, where m∈V{\mathbf m} \in \mathcal{V}m∈V is its one-hot vector. We define x1:L{\mathbf x}^{1:L}x1:L as a sequence of LLL tokens, where xℓ∈V{\mathbf x}^\ell \in \mathcal{V}xℓ∈V for all tokens ℓ∈{1,…,L},\ell \in \{1, \ldots, L\}, ℓ∈{1,…,L}, and use VL\mathcal{V}^LVL to denote the set of all such sequences. Throughout the work, we simplify notation and refer to the token sequence as x{\mathbf x}x and an individual token as xℓ{\mathbf x}^\ellxℓ. Finally, let Cat(⋅;p)\text{Cat}(\cdot; p)Cat(⋅;p) be a categorical distribution with probability p∈ΔVp \in \Delta^Vp∈ΔV.

2.1 Autoregressive Models

Consider a sequence of LLL tokens x=[x1,…,xL]{\mathbf x} = \left[{\mathbf x}^1, \dots, {\mathbf x}^L \right]x=[x1,…,xL] drawn from the data distribution q(x)q({\mathbf x})q(x). Autoregressive (AR) models define a factorized distribution of the form

where each pθ(xℓ∣x<ℓ)p_\theta({\mathbf x}^\ell \mid {\mathbf x}^{<\ell})pθ(xℓ∣x<ℓ) is parameterized directly with a neural network. As a result, AR models may be trained efficiently via next token prediction. However, AR models take LLL steps to generate LLL tokens due to the sequential dependencies.

2.2 Discrete Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models

Diffusion models fit a model pθ(x)p_\theta(\mathbf{x})pθ(x) to reverse a forward corruption process qqq ([21, 1, 3]). This process starts with clean data x\mathbf{x}x and defines latent variables xt=[xt1,…,xtL]\mathbf{x}_t = \left[\mathbf{x}^1_t, \dots, \mathbf{x}^L_t\right]xt=[xt1,…,xtL] for t∈[0,1]t \in [0, 1]t∈[0,1], which represent progressively noisier versions of x\mathbf{x}x. Given a discretization into TTT steps, we define s(j)=(j−1)/Ts(j) = (j -1)/Ts(j)=(j−1)/T and t(j)=j/Tt(j) = j /Tt(j)=j/T. For brevity, we drop jjj from t(j)t(j)t(j) and s(j)s(j)s(j) below; in general, sss denotes the time step preceding ttt.

The D3PM framework ([14]) defines qqq as a Markov forward process acting independently on each token xℓ\mathbf{x}^\ellxℓ: q(xtℓ∣xsℓ)=Cat(xtℓ;Qtxsℓ)q(\mathbf{x}^\ell_{t} \mid \mathbf{x}^\ell_{s}) = \operatorname{Cat}(\mathbf{x}^\ell_t ; Q_t \mathbf{x}^\ell_{s})q(xtℓ∣xsℓ)=Cat(xtℓ;Qtxsℓ) where Qt∈RV×VQ_t \in \mathbb{R}^{V \times V}Qt∈RV×V is the diffusion matrix. The matrix QtQ_tQt can model various transformations, including masking, random token changes, and related word substitutions.

An ideal diffusion model pθ{p_\theta}pθ is the reverse of the process qqq. The D3PM framework defines pθ{p_\theta}pθ as

where the denoising base model pθ(xℓ∣xt){p_\theta}({\mathbf x}^\ell \mid {\mathbf x}_t)pθ(xℓ∣xt) predicts clean token xℓ{\mathbf x}^\ellxℓ given the noisy sequence xt\mathbf{x}_txt, and the reverse posterior q(xsℓ∣xtℓ,x)q(\mathbf{x}^\ell_s \mid \mathbf{x}^\ell_t, \mathbf{x})q(xsℓ∣xtℓ,x) is defined following [14] in Suppl. Appendix B.3.

The diffusion model pθp_\thetapθ is trained using variational inference. Let KL[⋅]\operatorname{KL}[\cdot]KL[⋅] denote the Kullback-Leibler divergence. Then, the Negative ELBO (NELBO) is given by ([21]):

This formalism extends to continuous time via Markov chain (CTMC) theory and admits score-based generalizations ([22, 6, 23]). Further simplifications ([7, 24, 25]) tighten the ELBO and enhance performance.

3. Block Diffusion Language Modeling

In this section, Block Discrete Denoising Diffusion Language Models (BD3-LMs) are introduced as a hybrid approach that combines autoregressive and diffusion modeling by factorizing sequences into blocks and applying discrete diffusion within each block while modeling blocks autoregressively. The model uses a single transformer with block-causal attention to parameterize all block-conditional distributions, outputting denoised token predictions along with key-value caches for efficient computation. A novel training algorithm minimizes computational overhead by precomputing keys and values for clean sequences, then denoising each block using cached context, with a vectorized implementation enabling parallel loss computation across all blocks in one forward pass. For sampling, blocks are generated sequentially using cached keys and values from previous blocks, with parallel token generation within each block. This architecture overcomes key limitations of pure diffusion models by enabling variable-length generation through sequential block sampling and improving inference efficiency through KV caching, while maintaining the parallel generation benefits of diffusion within blocks.

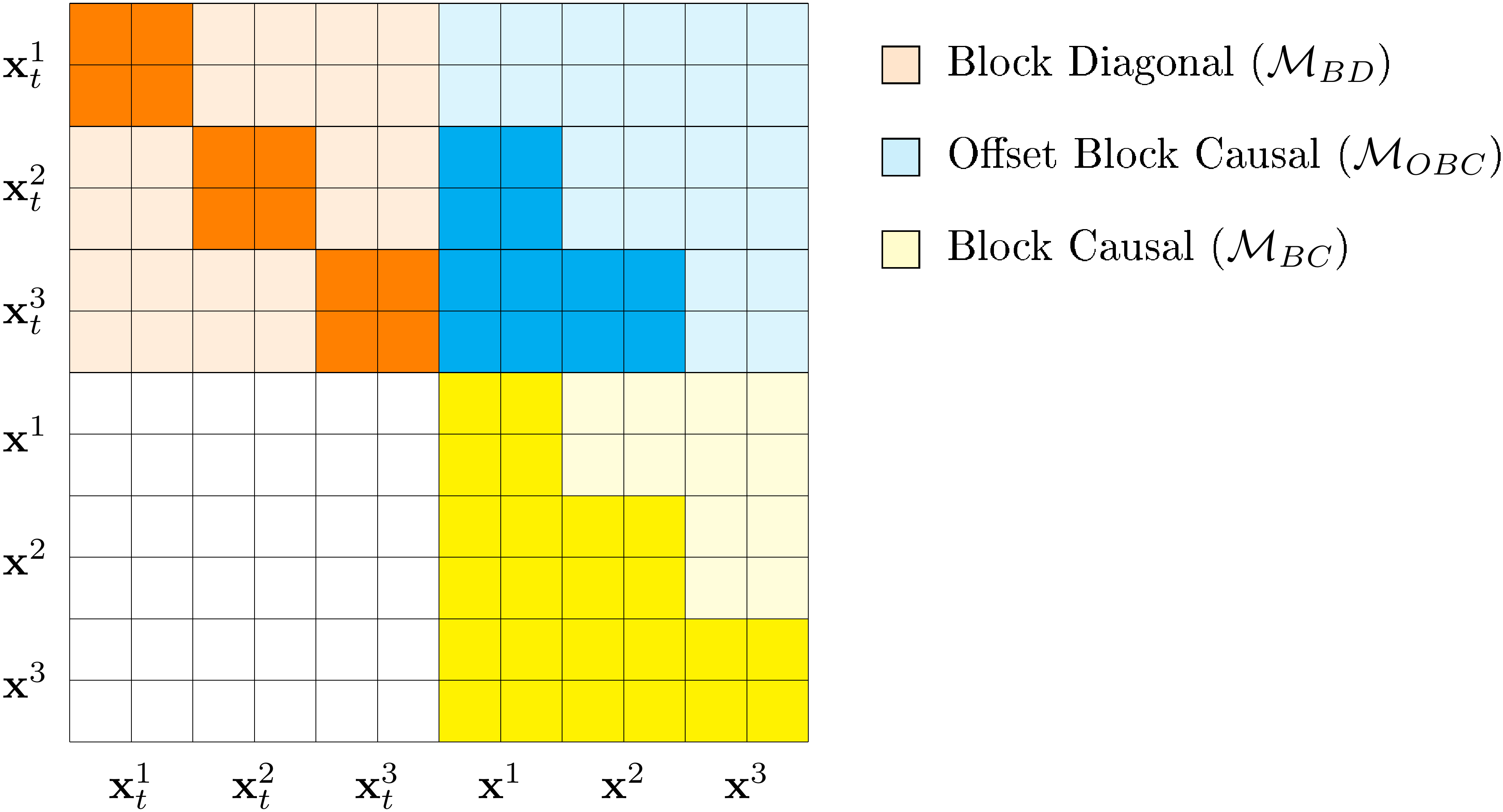

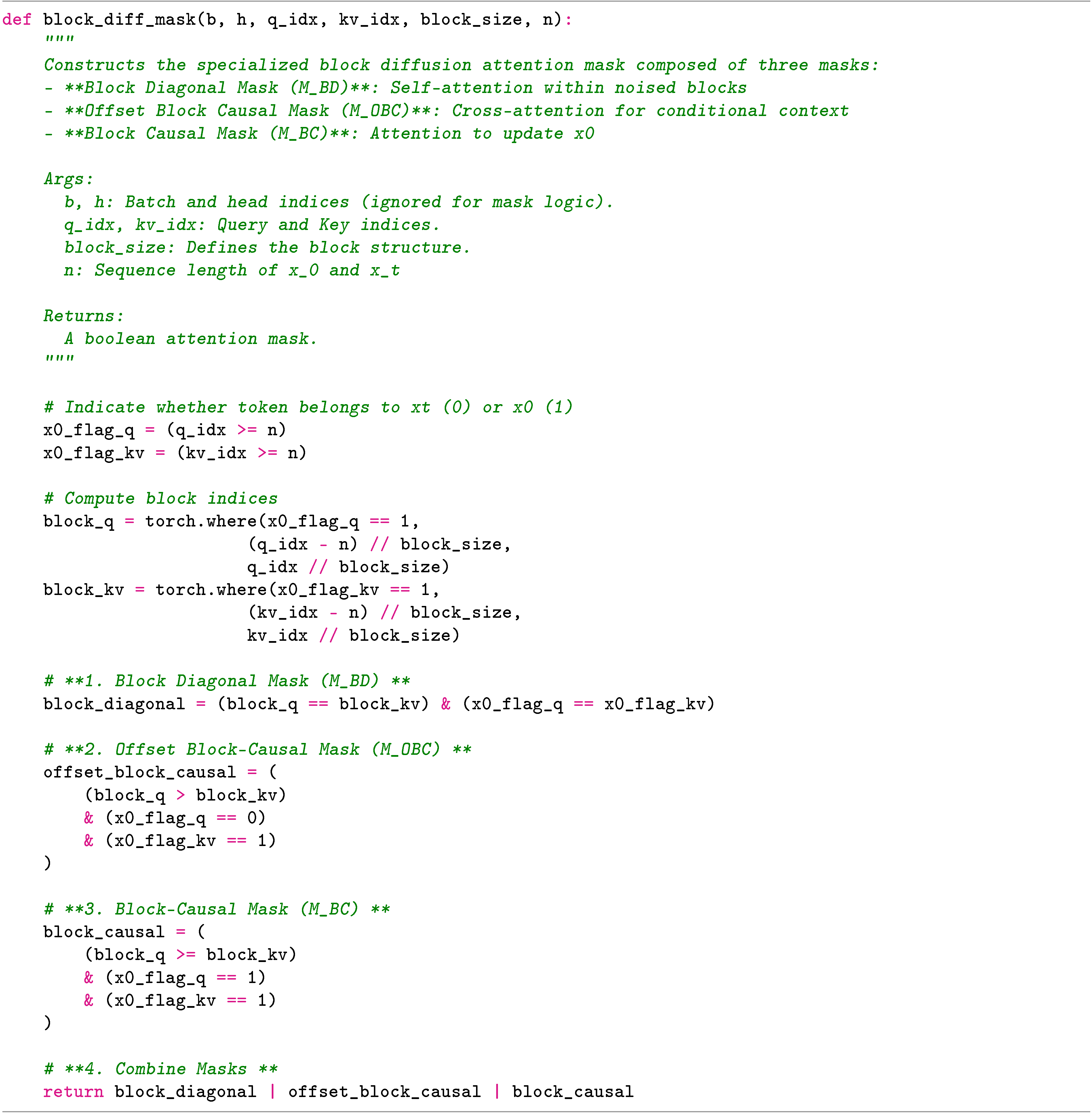

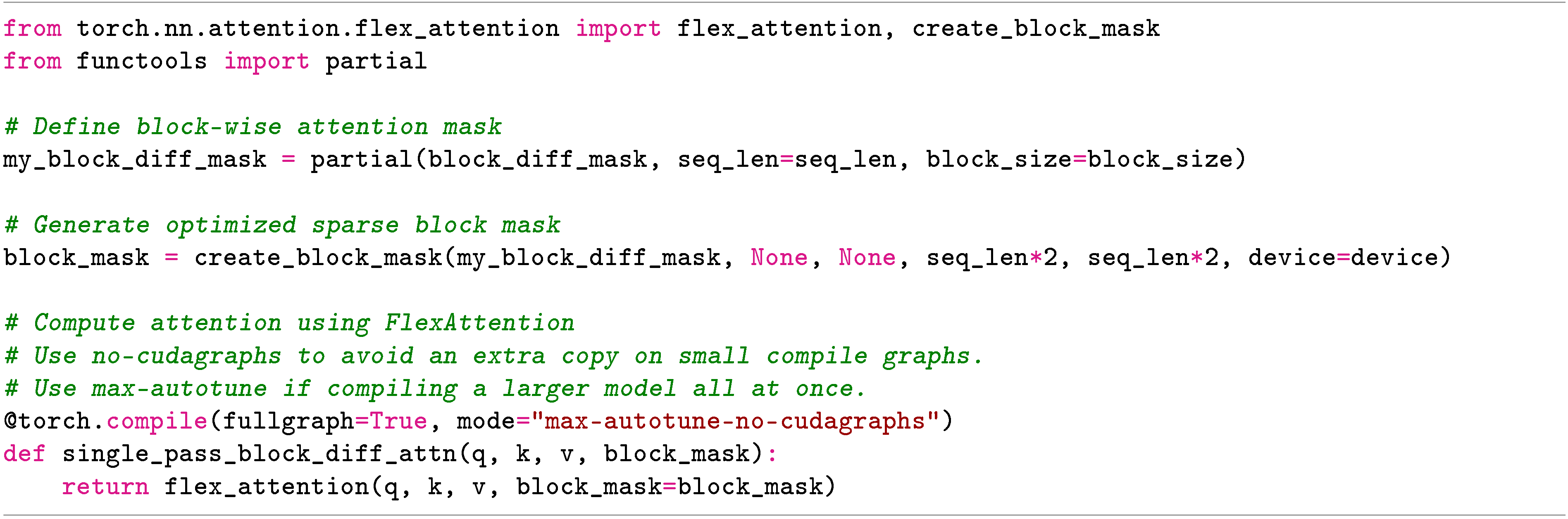

In this section, the authors provide the mathematical foundations and technical details for Block Diffusion Discrete Denoising Language Models (BD3-LMs), beginning with the derivation of the block diffusion Negative Evidence Lower Bound (NELBO) that factorizes sequences into blocks and applies diffusion within each block conditioned on previous blocks. They then specialize to masked diffusion processes, showing how the NELBO simplifies in continuous time to a weighted cross-entropy objective that is invariant to noise schedules, and prove that for single-token blocks this recovers the standard autoregressive negative log-likelihood, establishing that the NELBO tightness increases monotonically with block size. The appendix introduces specialized block-diagonal and offset block-causal attention masks that enable efficient simultaneous processing of noised sequences and conditional contexts by concatenating them and using structured sparse attention, which is optimized through FlexAttention to exploit sparsity and achieve significant computational speedups during training while maintaining the mathematical correctness of the block diffusion framework.

We explore a class of Block Discrete Denoising Diffusion Language Models (BD3-LMs) that interpolate between autoregressive and diffusion models by defining an autoregressive distribution over blocks of tokens and performing diffusion within each block. We provide a block diffusion objective for maximum likelihood estimation and efficient training and sampling algorithms. We show that for a block size of one, the diffusion objective suffers from high variance despite being equivalent to the autoregressive likelihood in expectation. We identify high training variance as a limitation of diffusion models and propose data-driven noise schedules that reduce the variance of the gradient updates during training.

3.1 Block Diffusion Distributions and Model Architectures

We propose to combine the language modeling paradigms in Section 2 by autoregressively modeling blocks of tokens and performing diffusion within each block. We group tokens in x{\mathbf x}x into BBB blocks of length L′L'L′ with B=L/L′B=L/L'B=L/L′ (we assume that BBB is an integer). We denote each block x(b−1)L′:bL′{\mathbf x}^{(b-1)L':bL'}x(b−1)L′:bL′ from token at positions (b−1)L′(b-1)L'(b−1)L′ to bL′bL'bL′ for blocks b∈{1,…,B}b \in \{ 1, \dots, B \}b∈{1,…,B} as xb{\mathbf x}^bxb for simplicity. Our likelihood factorizes over blocks as

and each pθ(xb∣x<b)p_\theta({\mathbf x}^b \mid {\mathbf x}^{<b})pθ(xb∣x<b) is modeled using discrete diffusion over a block of L′L'L′ tokens. Specifically, we define a reverse diffusion process as in (Equation 2), but restricted to block bbb:

We obtain a principled learning objective by applying the NELBO in (Equation 3) to each term in (Equation 4) to obtain

where each L(xb,x<b;θ)\mathcal{L}({\mathbf x}^b, {\mathbf x}^{<b}; \theta)L(xb,x<b;θ) is an instance of (Equation 3) applied to logpθ(xb∣x<b)\log p_\theta({\mathbf x}^{b} \mid {\mathbf x}^{<b})logpθ(xb∣x<b). Since the model is conditioned on x<b{\mathbf x}^{<b}x<b, we make the dependence on x<b,θ{\mathbf x}^{<b}, \thetax<b,θ explicit in L\mathcal{L}L. We denote the sum of these terms LBD(x;θ)\mathcal{L}_\text{BD}({\mathbf x}; \theta)LBD(x;θ) (itself a valid NELBO).

Model Architecture Crucially, we parameterize the BBB base denoiser models pθ(xb∣xtb,x<b)p_\theta({\mathbf x}^b \mid {\mathbf x}^b_t, {\mathbf x}^{<b})pθ(xb∣xtb,x<b) using a single neural network xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ. The neural network xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ outputs not only the probabilities pθ(xb∣xtb,x<b)p_\theta({\mathbf x}^b \mid {\mathbf x}_t^b, {\mathbf x}^{<b})pθ(xb∣xtb,x<b), but also computational artifacts for efficient training. This will enable us to compute the loss LBD(x;θ)\mathcal{L}_\text{BD}({\mathbf x}; \theta)LBD(x;θ) in parallel for all BBB blocks in a memory-efficient manner. Specifically, we parameterize xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ using a transformer ([26]) with a block-causal attention mask. The transformer xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ is applied to LLL tokens, and tokens in block bbb attend to tokens in blocks 1 to bbb. When xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ is trained, xθb(xtb,x<b){\mathbf x}^b_\theta({\mathbf x}^b_t, {\mathbf x}^{<b})xθb(xtb,x<b) yields L′L'L′ predictions for denoised tokens in block bbb based on noised xtb{\mathbf x}^b_txtb and clean x<b{\mathbf x}^{<b}x<b.

In autoregressive generation, it is normal to cache keys and values for previously generated tokens to avoid recomputing them at each step. Similarly, we use Kb,Vb\mathbf{K}^b, \mathbf{V}^bKb,Vb to denote the keys and values at block bbb, and we define xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ to support these as input and output. The full signature of xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ is

where xlogitsb{\mathbf x}_\text{logits}^bxlogitsb are the predictions for the clean xb{\mathbf x}^bxb, and Kb,Vb\mathbf{K}^b, \mathbf{V}^bKb,Vb is the key-value cache in the forward pass of xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ, and K1:b−1,V1:b−1\mathbf{K}^{1:b-1}, \mathbf{V}^{1:b-1}K1:b−1,V1:b−1 are keys and values cached on a forward pass of xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ over x<b{\mathbf x}^{<b}x<b (hence the inputs x<b{\mathbf x}^{<b}x<b and K1:b−1,V1:b−1\mathbf{K}^{1:b-1}, \mathbf{V}^{1:b-1}K1:b−1,V1:b−1 are equivalent).

3.2 Efficient Training and Sampling Algorithms

Ideally, we wish to compute the loss LBD(x;θ)\mathcal{L}_\text{BD}({\mathbf x}; \theta)LBD(x;θ) in one forward pass of xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ. However, observe that denoising xtb{\mathbf x}_t^bxtb requires a forward pass on this noisy input, while denoising the next blocks requires running xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ on the clean version xb{\mathbf x}^bxb. Thus every block has to go through the model at least twice.

Training Based on this observation, we propose a training algorithm with these minimal computational requirements (Algorithm 1). Specifically, we precompute keys and values K1:B,V1:B\mathbf{K}^{1:B}, \mathbf{V}^{1:B}K1:B,V1:B for the full sequence x{\mathbf x}x in a first forward pass (∅,K1:B,V1:B)←xθ(x)(\emptyset, \mathbf{K}^{1:B}, \mathbf{V}^{1:B}) \gets {\mathbf x}_\theta({\mathbf x})(∅,K1:B,V1:B)←xθ(x). We then compute denoised predictions for all blocks using xθb(xtb,K1:b-1,V1:b-1){\mathbf x}_\theta^b({\mathbf x}_{t}^b, \mathbf{K}^{1:b\text{-}1}, \mathbf{V}^{1:b\text{-}1})xθb(xtb,K1:b-1,V1:b-1). Each token passes through xθ{\mathbf x}_\thetaxθ twice.

Vectorized Training Naively, we would compute the logits by applying xθb(xtb,K1:b-1,V1:b-1){\mathbf x}_\theta^b({\mathbf x}_{t}^b, \mathbf{K}^{1:b\text{-}1}, \mathbf{V}^{1:b\text{-}1})xθb(xtb,K1:b-1,V1:b-1) in a loop BBB times. We propose a vectorized implementation that computes LBD(x;θ)\mathcal{L}_\text{BD}({\mathbf x}; \theta)LBD(x;θ) in one forward pass on the concatenation xnoisy⊕x{\mathbf x}_\text{noisy} \oplus {\mathbf x}xnoisy⊕x of clean data x{\mathbf x}x with noisy data xnoisy=xt11⊕⋯⊕xtBB{\mathbf x}_\text{noisy} = {\mathbf x}^1_{t_1} \oplus \dots \oplus {\mathbf x}^B_{t_B}xnoisy=xt11⊕⋯⊕xtBB obtained by applying a noise level tbt_btb to each block xb{\mathbf x}^bxb. We design an attention mask for xnoisy⊕x{\mathbf x}_\text{noisy} \oplus {\mathbf x}xnoisy⊕x such that noisy tokens attend to other noisy tokens in their block and to all clean tokens in preceding blocks (see Suppl. Appendix B.6). Our method keeps the overhead of training BD3-LMs tractable and combines with pretraining to further reduce costs.

Sampling We sample one block at a time, conditioned on previously sampled blocks (Algorithm 2). We may use any sampling procedure SAMPLE(xθb,K1:b-1,V1:b-1)\text{S{\scriptsize AMPLE}}({\mathbf x}_\theta^b, \mathbf{K}^{1:b\text{-}1}, \mathbf{V}^{1:b\text{-}1})SAMPLE(xθb,K1:b-1,V1:b-1) to sample from the conditional distribution pθ(xsb∣xtb,x<b)p_\theta({\mathbf x}_{s}^b | {\mathbf x}_{t}^b, {\mathbf x}^{<b})pθ(xsb∣xtb,x<b), where the context conditioning is generated using cross-attention with pre-computed keys and values K1:b−1,V1:b−1\mathbf{K}^{1:b-1}, \mathbf{V}^{1:b-1}K1:b−1,V1:b−1. Similar to AR models, caching the keys and values saves computation instead of recalculating them when sampling a new block.

Notably, our block diffusion decoding algorithm enables us to sample sequences of arbitrary length, whereas diffusion models are restricted to fixed-length generation. Further, our sampler admits parallel generation within each block, whereas AR samplers are constrained to generate token-by-token.

4. Understanding Likelihood Gaps Between Diffusion & AR Models

4.1 Masked BD3-LMs

The most effective diffusion language models leverage a masking noise process ([14, 6, 7]), where tokens are gradually replaced with a special mask token. Here, we introduce masked BD3-LMs, a special class of block diffusion models based on the masked diffusion language modeling framework ([7, 24, 25]).

More formally, we adopt a per-token noise process q(xtℓ∣xℓ)=Cat(xtℓ;αtxℓ+(1−αt)m)q({\mathbf x}^\ell_t| {\mathbf x}^\ell) = \text{Cat}({\mathbf x}^\ell_t; \alpha_{t} {\mathbf x}^\ell + (1 - \alpha_{t}) {\mathbf m})q(xtℓ∣xℓ)=Cat(xtℓ;αtxℓ+(1−αt)m) for tokens ℓ∈{1,…,L}\ell \in \{1, \dots, L\}ℓ∈{1,…,L} where m{\mathbf m}m is a one-hot encoding of the mask token, and αt∈[0,1]\alpha_t \in [0, 1]αt∈[0,1] is a strictly decreasing function in ttt, with α0=1\alpha_{0} = 1α0=1 and α1=0\alpha_{1} = 0α1=0. We employ the linear schedule where the probability of masking a token at time ttt is 1−αt1-\alpha_t1−αt. We adopt the simplified objective from [7, 24, 25] (the full derivation is provided in Suppl. Appendix B.3):

where αt′\alpha_{t}'αt′ is the instantaneous rate of change of αt\alpha_{t}αt under the continuous-time extension of (Equation 3) that takes T→∞T \rightarrow \inftyT→∞. The NELBO is tight for L′=1L'=1L′=1 but becomes a looser approximation of the true negative log-likelihood for L′→LL' \rightarrow LL′→L (see Suppl. Appendix B.5).

4.2 Case Study: Single Token Generation

Our block diffusion parameterization (Equation 7) is equivalent in expectation to the autoregressive NLL (Equation 1) in the limiting case where L′=1L'=1L′=1 (see Suppl. Appendix B.4). Surprisingly, we find a two point perplexity gap between our block diffusion model for L′=1L'=1L′=1 and AR when training both models on the LM1B dataset.

Although the objectives are equivalent in expectation, we show that the remaining perplexity gap is a result of high training variance. Whereas AR is trained using the cross-entropy of LLL tokens, our block diffusion model for L′=1L'=1L′=1 only computes the cross-entropy for masked tokens xtℓ=m ∀ℓ∈{1,…L}{\mathbf x}^\ell_t = {\mathbf m} \; \forall \ell \in \{ 1, \dots L \}xtℓ=m∀ℓ∈{1,…L} so that Et∼U[0,1]q(xtℓ=m∣xℓ)=0.5\mathbb{E}_{t \sim \mathcal{U}[0, 1]} q({\mathbf x}^\ell_t = {\mathbf m} | {\mathbf x}^\ell) = 0.5Et∼U[0,1]q(xtℓ=m∣xℓ)=0.5. Thus, training on the diffusion objective involves estimating loss gradients with 2x fewer tokens and is responsible for higher training variance compared to AR.

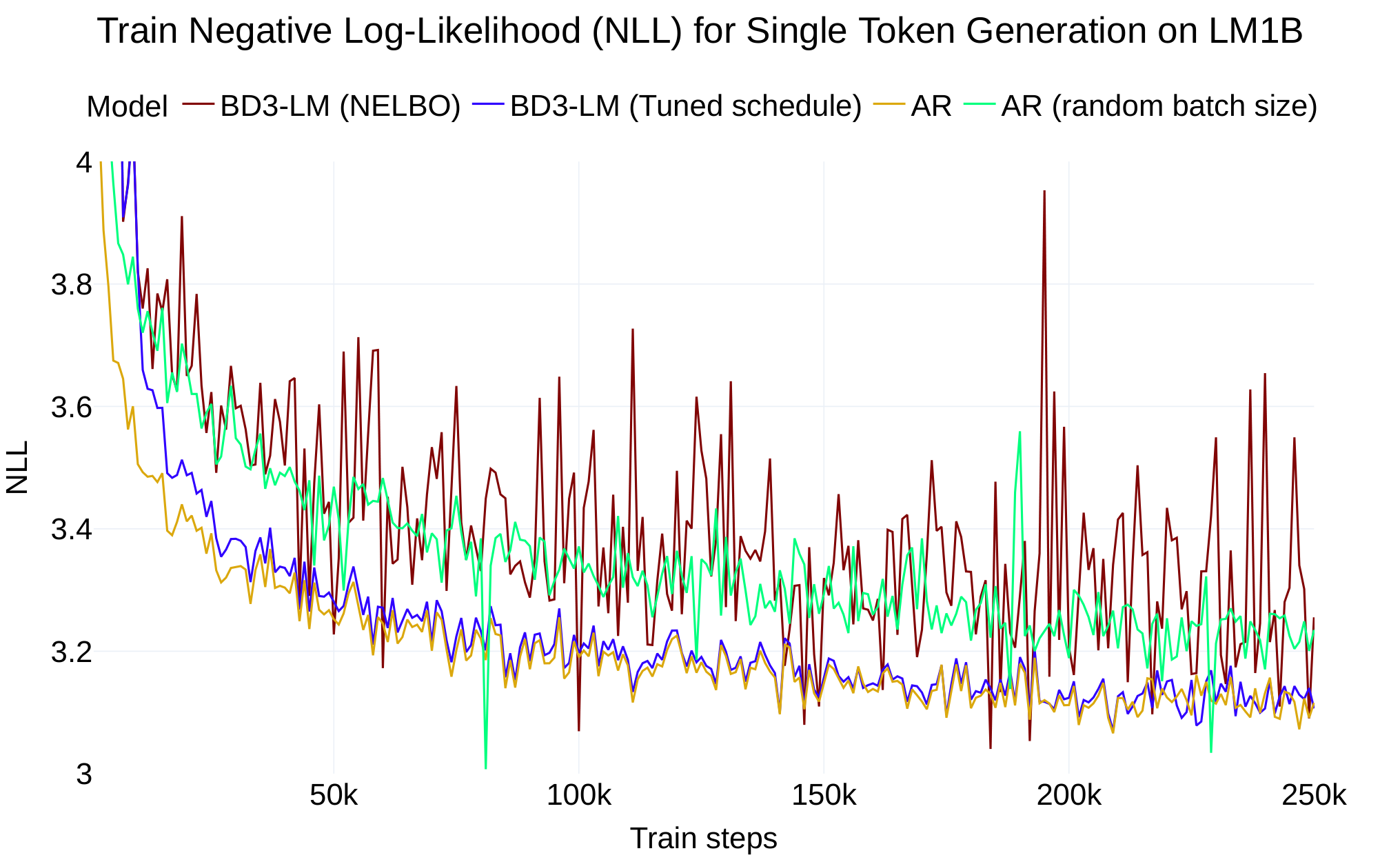

To close the likelihood gap, we train a BD3-LM for L′=1L'=1L′=1 by designing the forward process to fully mask tokens, i.e. q(xtℓ=m∣xℓ)=1q({\mathbf x}^\ell_t = {\mathbf m} | {\mathbf x}^\ell) =1q(xtℓ=m∣xℓ)=1. Under this schedule, the diffusion objective becomes equivalent to the AR objective (Suppl. Appendix B.4). In Table 1, we show that training under the block diffusion objective yields the same perplexity as AR training. Empirically, we see that this reduces the variance of the training loss in Figure 2. We verify that tuning the noise schedule reduces the variance of the objective by measuring Varx,t[LBD(x;θ)]\text{Var}_{{\mathbf x}, t} \left[\mathcal{L}_{\text{BD}} ({\mathbf x}; \theta)\right]Varx,t[LBD(x;θ)] after training on 328M tokens: while training on the NELBO results in a variance of 1.52, training under full masking reduces the variance to 0.11.

4.3 Diffusion Gap from High Variance Training

Next, we formally describe the issue of gradient variance in training diffusion models. Given our empirical observations for single-token generation, we propose an estimator for gradient variance that we use to minimize the variance of diffusion model training for L′≥1L' \geq 1L′≥1. While the NELBO is invariant to the choice of noise schedule (Suppl. Appendix B.3), this invariance does not hold for our Monte Carlo estimator of the loss used during training. As a result, the variance of the estimator and its gradients are dependent on the schedule. First, we express the estimator of the NELBO with a batch size KKK. We denote a batch of sequences as X=[x(1),x(2),…,x(K)]\mathbf{X} = \left[{\mathbf x}^{(1)}, {\mathbf x}^{(2)}, \ldots, {\mathbf x}^{(K)}\right]X=[x(1),x(2),…,x(K)], with each x(k)∼iidq(x){\mathbf x}^{(k)}\overset{\text{iid}}\sim q({\mathbf x})x(k)∼iidq(x). We obtain the batch NELBO estimator below, where t(k,b)t(k, b)t(k,b) is sampled in sequence kkk and block bbb:

The variance of the gradient estimator over MMM batches for each batch Xm ∀m∈{1,…,M}\mathbf{X}^m \; \forall m \in \{ 1, \dots, M\}Xm∀m∈{1,…,M} is:

5. Low-Variance Noise Schedules for BD3-LMs

In this section, the authors address the challenge of high-variance gradient estimation in training block diffusion language models by designing optimized noise schedules that avoid extreme masking rates. They propose "clipped" schedules that sample mask rates uniformly from a restricted range, avoiding both minimal masking (which provides trivial reconstruction tasks) and complete masking (which reduces to learning marginal token distributions), as both extremes yield poor learning signals and high-variance gradients. These clipped schedules are parameterized by bounds beta and omega, which are adaptively optimized during training through periodic grid searches to minimize the variance of the diffusion objective across different block sizes. Experimental results demonstrate that variance of the NELBO correlates strongly with test perplexity, and that optimal clipping ranges are block-size-specific: larger blocks benefit from lighter masking while smaller blocks require heavier masking. This data-driven approach to schedule selection enables BD3-LMs to achieve lower perplexity than previous diffusion models while maintaining training efficiency.

5.1 Intuition: Avoid Extreme Mask Rates

We aim to identify schedules that minimize the variance of the gradient estimator and make training most efficient. In a masked setting, we want to mask random numbers of tokens, so that the model learns to undo varying levels of noise, which is important during sampling. However, if we mask very few tokens, reconstructing them is easy and does not provide useful learning signal. If we mask everything, the optimal reconstruction are the marginals of each token in the data distribution, which is easy to learn, and again is not useful. These extreme masking rates lead to poor high-variance gradients: we want to learn how to clip them via a simple and effective new class of schedules.

5.2 Clipped Schedules for Low-Variance Gradients

We propose a class of "clipped" noise schedules that sample mask rates 1−αt∼U[β,ω]1- \alpha_{t} \sim \mathcal{U}[\beta, \omega]1−αt∼U[β,ω] for 0≤β,ω≤10 \leq \beta, \omega \leq 10≤β,ω≤1. We argue that from the perspective of deriving Monte Carlo gradient estimates, these schedules are equivalent to a continuous schedule where the mask probability is approximately 0 before the specified range such that 1−α<β≈ϵ1-\alpha_{<\beta} \approx \epsilon1−α<β≈ϵ and approximately 1 after the specified range 1−α>ω≈1−ϵ1-\alpha_{>\omega} \approx 1-\epsilon1−α>ω≈1−ϵ. Consequently, αt′\alpha_{t}'αt′ is linear within the range: αt′≈1/(β−ω)\alpha_{t}' \approx 1 / (\beta - \omega)αt′≈1/(β−ω).

5.3 Data-Driven Clipped Schedules Across Block Sizes

As the optimal mask rates may differ depending on the block size L′L'L′, we adaptively learn the schedule during training. While [27] perform variance minimization by isolating a variance term using their squared diffusion loss, this strategy is not directly applicable to our variance estimator in Equation 8 since we seek to reduce variance across random batches in addition to random tbt_btb.

Instead, we optimize parameters β,ω\beta, \omegaβ,ω to directly minimize training variance. To limit the computational burden of the optimization, we use the variance of the estimator of the diffusion ELBO as a proxy for the gradient estimator to optimize β,ω\beta, \omegaβ,ω: minβ,ωVarX,t[L(X;θ,β,ω)]\min_{\beta, \omega} \text{Var}_{\mathbf{X}, t} \left[\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{X}; \theta, \beta, \omega) \right]minβ,ωVarX,t[L(X;θ,β,ω)]. We perform a grid search at regular intervals during training to find the optimal β,ω\beta, \omegaβ,ω (experimental details in Section 6).

In Table 2, we show that variance of the diffusion NELBO is correlated with test perplexity. Under a range of "clipped" noise rate distributions, we find that there exists a unique distribution for each block size L′∈{4,16,128}L' \in \{4, 16, 128\}L′∈{4,16,128} that minimizes both the variance of the NELBO and the test perplexity.

6. Experiments

In this section, the authors evaluate BD3-LMs on standard language modeling benchmarks to demonstrate their superiority over existing diffusion methods in both likelihood estimation and variable-length sequence generation. BD3-LMs achieve up to 13% perplexity improvement over MDLM on LM1B and outperform all prior diffusion models on OpenWebText, with smaller block sizes yielding better results. Zero-shot evaluation across multiple datasets shows BD3-LMs achieve the best diffusion perplexities on Wikitext, LM1B, and AG News, even surpassing autoregressive models on Pubmed. Unlike prior diffusion methods constrained to fixed-length outputs, BD3-LMs generate sequences up to 10 times longer than SEDD while maintaining superior sample quality, achieving generative perplexities of 23.6 compared to MDLM's 41.3 for 2048-token sequences. Ablations confirm that optimized clipped noise schedules reduce training variance and improve perplexity, while the vectorized training algorithm provides 20-25% speedup over naive implementations.

We evaluate BD3-LMs across standard language modeling benchmarks and demonstrate their ability to generate arbitrary-length sequences unconditionally. We pre-train a base BD3-LM using the maximum block size L′=LL'=LL′=L for 850K gradient steps and fine-tune under varying L′L'L′ for 150K gradient steps on the One Billion Words dataset (LM1B; [29]) and OpenWebText (OWT; [30]). Details on training and inference are provided in Suppl Appendix C.

To reduce the variance of training on the diffusion NELBO, we adaptively learn the range of masking rates by optimizing parameters β,ω\beta, \omegaβ,ω as described in Section 5.3. In practice, we do so using a grid search during every validation epoch (after ∼\sim∼ 5K gradient updates) to identify β,ω\beta, \omegaβ,ω: minβ,ωVarX,t[L(X;θ,β,ω)]\min_{\beta, \omega} \text{Var}_{\mathbf{X}, t} \left[\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{X}; \theta, \beta, \omega) \right]minβ,ωVarX,t[L(X;θ,β,ω)]. During evaluation, we report likelihood under uniformly sampled mask rates (Equation 7) as in [14, 7].

6.1 Likelihood Evaluation

On LM1B, BD3-LMs outperform all prior diffusion methods in Table 3. Compared to MDLM ([7]), BD3-LMs achieve up to 13% improvement in perplexity. We observe a similar trend on OpenWebText in Table 4.

We also evaluate the ability of BD3-LMs to generalize to unseen datasets in a zero-shot setting, following the benchmark from [31]. We evaluate the likelihood of models trained with OWT on datasets Penn Tree Bank (PTB; ([32])), Wikitext ([33]), LM1B, Lambada ([34]), AG News ([35]), and Scientific Papers (Pubmed and Arxiv subsets; ([36])). In Table 5, BD3-LM achieves the best zero-shot perplexity on Pubmed, surpassing AR, and the best perplexity among diffusion models on Wikitext, LM1B, and AG News.

6.2 Sample Quality and Variable-Length Sequence Generation

One key drawback of many existing diffusion language models (e.g, . [14, 6]) is that they cannot generate full-length sequences that are longer than the length of the output context chosen at training time. The OWT dataset is useful for examining this limitation, as it contains many documents that are longer than the training context length of 1024 tokens.

We record generation length statistics of 500 variable-length samples in Table 6. We continue sampling tokens until an end-of-sequence token [EOS] is generated or sample quality significantly degrades (as measured by sample entropy). BD3-LMs generate sequences up to ≈\approx≈ 10 ×\times× longer than those of SEDD ([6]), which is restricted to the training context size.

We also examine the sample quality of BD3-LMs through quantitative and qualitative analyses. In Table 7, we generate sequences of lengths L=1024,2048L=1024, 2048L=1024,2048 and measure their generative perplexity under GPT2-Large. To sample L=2048L=2048L=2048 tokens from MDLM, we use their block-wise decoding technique (which does not feature block diffusion training as in BD3-LMs).

We also compare to SSD-LM ([19]), an alternative block diffusion formulation. Unlike our discrete diffusion framework, SSD-LM uses Gaussian diffusion and does not support likelihood estimation. Further, BD3-LM adopts an efficient sampler from masked diffusion, where the number of generation steps (NFEs) is upper-bounded by LLL since tokens are never remasked ([7, 25]). For SSD-LM, we compare sample quality using T=1T=1T=1 K diffusion steps per block, matching their experimental setting (yielding ≥\geq≥ 40K NFEs), and T=25T=25T=25 where NFEs are comparable across methods.

BD3-LMs achieve the best generative perplexities compared to previous diffusion methods. Relative to SSD-LM, our discrete approach yields samples with improved generative perplexity using an order of magnitude fewer generation steps. We also qualitatively examine samples taken from BD3-LM and baselines (AR, MDLM) trained on the OWT dataset; we report samples in Suppl. Appendix D. We observe that BD3-LM samples have higher coherence than MDLM samples and approach the quality of AR.

6.3 Ablations

We assess the impact of the design choices in our proposed block diffusion recipes, namely 1) selection of the noise schedule and 2) the efficiency improvement of the proposed training algorithm relative to a naive implementation.

Selecting Noise Schedules to Reduce Training Variance

Compared to the linear schedule used in [6, 7], training under "clipped" noise schedules is the most effective for reducing the training variance which correlates with test perplexity. In Table 8, the ideal "clipped" masking rates, which are optimized during training, are specific to the block size and further motivate our optimization.

Relative to other standard noise schedules ([37]), "clipped" masking achieves the best performance. As heavier masking is effective for the smaller block size L′=4L'=4L′=4, we compare with logarithmic and square root schedules that also encourage heavy masking. As lighter masking is optimal for L′=16L'=16L′=16, we compare with square and cosine schedules.

Efficiency of Training Algorithm

In the BD3-LM training algorithm (Section 3.2), we compute xlogit{\mathbf x}_{\text{logit}}xlogit using two options. We may perform two forward passes through the network (precomputing keys and values for the full sequence x{\mathbf x}x, then computing denoised predictions), or combine these passes by concatenating the two inputs into the same attention kernel.

We find that a single forward pass is more efficient as we reduce memory bandwidth bottlenecks by leveraging efficient attention kernels ([38, 39]), see Suppl. Appendix B.7. Instead of paying the cost of two passes through the network, we only pay the cost of a more expensive attention operation. Our vectorized approach has 20-25% speed-up during training relative to performing two forward passes.

7. Discussion and Prior Work

In this section, the authors position BD3-LMs relative to existing diffusion and autoregressive approaches for language modeling. Block diffusion extends D3PM by enabling variable-length generation, reducing gradient variance through optimized schedules, and improving perplexity. Compared to MDLM, BD3-LMs demonstrate that noise schedules significantly affect gradient variance despite theoretical invariance of the NELBO, achieving state-of-the-art perplexity among discrete diffusion models. Unlike Gaussian diffusion over continuous embeddings, the discrete formulation yields better perplexity. Relative to semi-autoregressive methods like SSD-LM, BD3-LMs provide tractable likelihood estimation, require orders of magnitude fewer generation steps, and produce higher-quality samples. The approach interpolates between autoregressive and diffusion performance while supporting efficient KV caching. However, training costs remain higher than standard diffusion (though within 2x via vectorization), sequential block generation inherits autoregressive speed constraints for small blocks, and optimal block size is task-dependent. BD3-LMs also face typical generative model limitations including hallucinations, copyright issues, and potential harmful outputs.

Comparison to D3PM Block diffusion builds off D3PM ([14]) and applies it to each autoregressive conditional. We improve over D3PM in three ways: (1) we extend D3PM beyond fixed sequence lengths; (2) we study the perplexity gap of D3PM and AR models, identify gradient variance as a contributor, and design variance-minimizing schedules; (3) we improve over the perplexity of D3PM models. Our work applies to extensions of D3PM ([40, 6]) including ones in continuous time ([41, 23]).

Comparison to MDLM BD3-LMs further make use of the perplexity-enhancing improvements in MDLM ([7, 24, 25]). We also build upon MDLM: (1) while [7] point out that their NELBO is invariant to the noise schedule, we show that the noise schedule has a significant effect on gradient variance; (2) we push the state-of-the-art in perplexity beyond MDLM. Note that our perplexity improvements stem not only from block diffusion, but also from optimized schedules, and could enhance standard MDLM and D3PM models.

Comparison to Gaussian Diffusion Alternatively, one may perform diffusion over continuous embeddings of discrete tokens ([42, 43, 44]). This allows using algorithms for continuous data ([45, 46]), but yields worse perplexity ([47, 16]).

Comparison to Semi-Autoregressive Diffusion [19, 20] introduced a block formulation of Gaussian diffusion. BD3-LMs instead extend [14], and feature: (1) tractable likelihood estimates for principled evaluation; (2) faster generation, as our number of model calls is bounded by the number of generated tokens, while SSD-LM performs orders of magnitude more calls; (3) improved sample quality. AR-Diffusion ([48]) extends SSD-LM with a left-to-right noise schedule; [49, 50] apply to decision traces and videos; [51, 52] extend to latent reasoning. PARD ([53]) applies discrete block diffusion to graphs. In contrast, we (1) interpolate between AR/diffusion performance; (2) support KV caching; (3) perform attention within noised blocks, whereas PARD injects new empty blocks.

Autoregressive diffusion models ([54, 55]) extend any-order AR models (AO-ARMs; [56]) to support parallel sampling. [57] prove equivalence between MDLM and AO-ARM training. Further extensions of ARMs that compete with diffusion include iterative editing ([58]), parallel and speculative decoding ([59, 60, 61, 62]), consistency training ([63]), guidance ([64]), and cross-modal extensions ([65, 66]).

Limitations Training BD3-LMs is more expensive than regular diffusion training. We propose a vectorized algorithm that keeps training speed within <2x of diffusion training speed; in our experiments, we also pre-train with a standard diffusion loss to further reduce the speed gap. Additionally, BD3-LMs generate blocks sequentially, and hence may face the same speed and controllability constraints as AR especially when blocks are small. Their optimal block size is task specific (e.g., larger for greater control). BD3-LMs are subject to inherent limitations of generative models, including hallucinations ([67]), copyright infringement ([68]), controllability ([10, 69]) and harmful outputs ([70]).

8. Conclusion

In this section, the authors address two critical limitations of existing discrete diffusion language models: the inability to generate arbitrary-length sequences and a significant perplexity gap compared to autoregressive models. They introduce BD3-LMs, a block-wise extension of the D3PM framework that applies diffusion within autoregressive blocks rather than across entire fixed-length sequences. The approach incorporates a specialized training algorithm that efficiently processes noised blocks and their conditional context simultaneously, along with custom "clipped" noise schedules optimized to reduce training variance. These design choices enable BD3-LMs to generate variable-length documents extending far beyond training context limits while simultaneously achieving state-of-the-art perplexity among discrete diffusion models, with improvements up to 13% over prior methods like MDLM. The work demonstrates that block diffusion successfully bridges the performance gap between fully parallel diffusion and sequential autoregressive generation.

This work explores block diffusion and is motivated by two problems with existing discrete diffusion: the need to generate arbitrary-length sequences and the perplexity gap to autoregressive models. We introduce BD3-LMs, which represent a block-wise extension of the D3PM framework ([14]), and leverage a specialized training algorithm and custom noise schedules that further improve performance. We observe that in addition to being able to generate long-form documents, these models also improve perplexity, setting a new state-of-the-art among discrete diffusion models.

Acknowledgments and Disclosure of Funding

This work was partially funded by the National Science Foundation under awards DGE-1922551, CAREER awards 2046760 and 2145577, and by the National Institute of Health under award MIRA R35GM151243. Marianne Arriola is supported by a NSF Graduate Research Fellowship under award DGE-2139899 and a Hopper-Dean/Bowers CIS Deans Excellence Fellowship. We thank Databricks MosaicML for providing access to computational resources.

Appendix

A. Block Diffusion NELBO

Below, we provide the Negative ELBO (NELBO) for the block diffusion parameterization. Recall that the sequence x1:L=[x1,…,xL]{\mathbf x}^{1:L} = \left[{\mathbf x}^1, \dots, {\mathbf x}^L \right]x1:L=[x1,…,xL] is factorized over BBB blocks, which we refer to as x{\mathbf x}x for simplicity, drawn from the data distribution q(x)q(\mathbf{x})q(x). Specifically, we will factorize the likelihood over BBB blocks of length L′L'L′, then perform diffusion in each block over TTT discretization steps. Let DKL[⋅]D_{\mathrm{KL}}[\cdot]DKL[⋅] to denote the Kullback-Leibler divergence, t,st, st,s be shorthand for t(i)=i/Tt(i) = i / Tt(i)=i/T and s(i)=(i−1)/Ts(i) = (i - 1)/Ts(i)=(i−1)/T ∀i∈[1,T]\forall i \in [1, T]∀i∈[1,T]. We derive the NELBO as follows:

B. Masked BD3-LMs

We explore a specific class of block diffusion models that builds upon the masked diffusion language modeling framework. In particular, we focus on masking diffusion processes introduced by [14] and derive a simplified NELBO under this framework as proposed by [7, 24, 25].

First, we define the diffusion matrix QtQ_tQt for states i∈{1,…,V}i \in \{1, \dots, V\}i∈{1,…,V}. Consider the noise schedule function αt∈[0,1]\alpha_t \in [0, 1]αt∈[0,1], which is a strictly decreasing function in ttt satisfying α0=1\alpha_{0} = 1α0=1 and α1=0\alpha_{1} = 0α1=0. Denote the mask index as m=Vm=Vm=V. The diffusion matrix is defined by [14] as:

The diffusion matrix for the forward marginal Qt∣sQ_{t|s}Qt∣s is:

where αt∣s=αt/αs\alpha_{t|s} = \alpha_{t} / \alpha_{s}αt∣s=αt/αs.

B.1 Forward Process

Under the D3PM framework ([14]), the forward noise process applied independently for each token ℓ∈{1,…L}\ell \in \{1, \dots L\}ℓ∈{1,…L} is defined using diffusion matrices Qt∈RV×VQ_t \in \mathbb{R}^{V \times V}Qt∈RV×V as

B.2 Reverse Process

Let Qt∣sQ_{t|s}Qt∣s denote the diffusion matrix for the forward marginal. We obtain the reverse posterior q(xsℓ∣xtℓ,xℓ)q({\mathbf x}^\ell_s \mid {\mathbf x}^\ell_t, {\mathbf x}^\ell)q(xsℓ∣xtℓ,xℓ) using the diffusion matrices:

where ⊙\odot⊙ denotes the Hadmard product between two vectors.

B.3 Simplified NELBO for Masked Diffusion Processes

Following [7, 24, 25], we simplify the NELBO in the case of masked diffusion processes. Below, we provide the outline of the NELBO derivation; see the full derivation in [7, 24, 25].

We will first focus on simplifying the diffusion loss term Ldiffusion\mathcal{L}_\text{diffusion}Ldiffusion in Equation 9. We employ the SUBS-parameterization proposed in [3] which simplifies the denoising model pθ{p_\theta}pθ for masked diffusion. In particular, we enforce the following constraints on the design of pθ{p_\theta}pθ by leveraging the fact that there only exists two possible states in the diffusion process xtℓ∈{xℓ,m} ∀ℓ∈{1,…,L}{\mathbf x}^\ell_t \in \{ {\mathbf x}^\ell, {\mathbf m} \} \; \forall \ell \in \{1, \dots, L\}xtℓ∈{xℓ,m}∀ℓ∈{1,…,L}.

- Zero Masking Probabilities. We set pθ(xℓ=m∣xtℓ)=0p_\theta({\mathbf x}^\ell = {\mathbf m} | {\mathbf x}^\ell_t) = 0pθ(xℓ=m∣xtℓ)=0 (as the clean sequence x{\mathbf x}x doesn't contain masks).

- Carry-Over Unmasking. The true posterior for the case where xtℓ≠m{\mathbf x}^\ell_t \neq {\mathbf m}xtℓ=m is q(xsℓ=xtℓ∣xtℓ≠m)=1q({\mathbf x}^\ell_s = {\mathbf x}^\ell_t | {\mathbf x}^\ell_t \neq {\mathbf m}) = 1q(xsℓ=xtℓ∣xtℓ=m)=1 (if a token is unmasked in the reverse process, it is never remasked). Thus, we simplify the denoising model by setting pθ(xsℓ=xtℓ∣xtℓ≠m)=1p_\theta ({\mathbf x}^\ell_s = {\mathbf x}^\ell_t | {\mathbf x}^\ell_t \neq {\mathbf m}) = 1pθ(xsℓ=xtℓ∣xtℓ=m)=1.

As a result, we will only approximate the posterior pθ(xsℓ=xℓ∣xtℓ=m){p_\theta}({\mathbf x}^\ell_s = {\mathbf x}^\ell | {\mathbf x}^\ell_t = {\mathbf m})pθ(xsℓ=xℓ∣xtℓ=m). Let xb,ℓ{\mathbf x}^{b, \ell}xb,ℓ denote a token in the ℓ\ellℓ-th position in block b∈{1,…,B}b \in \{1, \dots, B\}b∈{1,…,B}. The diffusion loss term becomes:

Lastly, we obtain a tighter approximation of the likelihood by taking the diffusion steps T→∞T \rightarrow \inftyT→∞ ([7]), for which T(αt−αs)=αt′T (\alpha_{t} - \alpha_{s}) = \alpha_{t}'T(αt−αs)=αt′:

For the continuous time case, [7] (Suppl. A.2.4) show the reconstruction loss reduces to 0 as xt(1)b∼limT→∞Cat(.;xt=1Tb)=Cat(.;xb){\mathbf x}_{t(1)}^b \sim \lim_{T \rightarrow \infty} \text{Cat}\left(.; {\mathbf x}_{t = \frac{1}{T}}^b\right) = \text{Cat}(.; {\mathbf x}^b)xt(1)b∼limT→∞Cat(.;xt=T1b)=Cat(.;xb). Using this, we obtain:

The prior loss Lprior=DKL(q(xt=1b∣xb)∥pθ(xt=1b))\mathcal{L}_\text{prior} = \text{D}_{KL} \left(q({\mathbf x}^{b}_{t=1} | {\mathbf x}^{b}) \parallel {p_\theta}({\mathbf x}^{b}_{t=1}) \right)Lprior=DKL(q(xt=1b∣xb)∥pθ(xt=1b)) also reduces to 0 because αt=1=0\alpha_{t=1} = 0αt=1=0 which ensures q(xt=1b∣xb)=Cat(.;m)q({\mathbf x}_{t=1}^b | {\mathbf x}^b) = \text{Cat} (. ; {\mathbf m})q(xt=1b∣xb)=Cat(.;m) and pθ(xt=1b)=Cat(.;m){p_\theta}({\mathbf x}_{t=1}^b) = \text{Cat} (. ; {\mathbf m})pθ(xt=1b)=Cat(.;m); see [7] (Suppl. A.2.4).

Finally, we obtain a simple objective that is a weighted average of cross-entropy terms:

The above NELBO is invariant to the choice of noise schedule αt\alpha_{t}αt; see [7] (Suppl. E.1.1).

B.4 Recovering the NLL from the NELBO for Single Token Generation

Consider the block diffuson NELBO for a block size of 1 where L′=1,B=LL'=1, B=LL′=1,B=L. The block diffusion NELBO is equivalent to the AR NLL when modeling a single token:

Recall that our denoising model employs the SUBS-parameterization proposed in [3]. The "carry-over unmasking" property ensures that logpθ(xb∣xtb=xb,x<b)=0\log p_\theta({\mathbf x}^b \mid {\mathbf x}_t^b = {\mathbf x}^b, {\mathbf x}^{<b})=0logpθ(xb∣xtb=xb,x<b)=0, as an unmasked token is simply copied over from from the input of the denoising model to the output. Hence, (Equation 10) reduces to following:

For single-token generation (L′=1L'=1L′=1) we recover the autoregressive NLL.

B.5 Tightness of the NELBO

For block sizes 1≤K≤L1 \leq K \leq L1≤K≤L, we show that - logp(x)≤LK≤LK+1\log p({\mathbf x}) \leq \mathcal{L}_{K} \leq \mathcal{L}_{K+1}logp(x)≤LK≤LK+1. Consider K=1K=1K=1, where we recover the autoregressive NLL (see Suppl Appendix B.4):

Consider the ELBO for block size K=2K=2K=2:

We show that L1≤L2\mathcal{L}_1 \leq \mathcal{L}_2L1≤L2, and this holds for all 1≤K≤L1 \leq K \leq L1≤K≤L by induction. Let xb,ℓ{\mathbf x}^{b, \ell}xb,ℓ correspond to the token in position ℓ∈[1,L′]\ell \in [1, L']ℓ∈[1,L′] of block bbb. We derive the below inequality:

B.6 Specialized Attention Masks

We aim to model conditional probabilities pθ(xb∣xtb,x<b)p_\theta({\mathbf x}^b \mid {\mathbf x}^b_t, {\mathbf x}^{<b})pθ(xb∣xtb,x<b) for all blocks b∈[1,B]b \in [1, B]b∈[1,B] simultaneously by designing an efficient training algorithm with our transformer backbone. However, modeling all BBB conditonal terms requires processing both the noised sequence xtb{\mathbf x}_t^bxtb and the conditional context x<b{\mathbf x}^{<b}x<b for all bbb.

Rather than calling the denoising network BBB times, we process both sequences simultaneously by concatenating them xfull←xt⊕x{\mathbf x}_{\text{full}} \gets {\mathbf x}_{t} \oplus {\mathbf x}xfull←xt⊕x as input to a transformer. We update this sequence xfull{\mathbf x}_{\text{full}}xfull of length 2L2L2L tokens using a custom attention mask Mfull∈{0,1}2L×2L\mathcal{M}_{\text{full}} \in \{ 0, 1\}^{2L \times 2L}Mfull∈{0,1}2L×2L for efficient training.

The full attention mask is comprised of four L×LL \times LL×L smaller attention masks:

where MBD\mathcal{M}_{BD}MBD and MOBC\mathcal{M}_{OBC}MOBC are used to update the representation of xt{\mathbf x}_txt and MBC\mathcal{M}_{BC}MBC is used to update the representation of x{\mathbf x}x. We define these masks as follows:

- MBD\mathcal{M}_{BD}MBD (Block-diagonal mask): Self-attention mask within noised blocks xtb{\mathbf x}_t^bxtb

- MOBC\mathcal{M}_{OBC}MOBC (Offset block-causal mask): Cross-attention to conditional context x<b{\mathbf x}^{<b}x<b

- MBC\mathcal{M}_{BC}MBC (Block-causal mask): Attention mask for updating xb{\mathbf x}^bxb

We visualize an example attention mask for L=6L = 6L=6 and block size L′=2L' = 2L′=2 in Figure 3.

B.7 Optimized Attention Kernel with FlexAttention

As Figure 3 demonstrates, our attention matrix is extremely sparse. We can exploit this sparsity to massively improve the efficiency of BD3-LMs.

FlexAttention ([39]) is a compiler-driven programming model that enables efficient implementation of attention mechanisms with structured sparsity in PyTorch. It provides a flexible interface for defining custom attention masks while maintaining high performance comparable to manually optimized attention kernels.

Below in Figure 4 we define a block-wise attention mask, block_diff_mask, based on its definition as Mfull∈{0,1}2L×2L\mathcal{M}_{\text{full}} \in \{0, 1\}^{2L \times 2L}Mfull∈{0,1}2L×2L in Suppl. Appendix B.6. We fuse the attention operations into a single FlexAttention kernel designed to exploit the sparsity in our attention matrix to increase computational efficiency. By doing so, we perform the following optimizations:

- Precomputed Block Masking: The

create_block_mask utility generates a sparse attention mask at compile-time, avoiding per-step computation of invalid attention entries. Through sparsity-aware execution, FlexAttention kernels reduce the number of FLOPs in the attention computation.

- Reduced Memory Footprint: By leveraging block-level sparsity, the attention mechanism avoids full materialization of large-scale attention matrices, significantly reducing memory overhead. FlexAttention minimizes memory accesses by skipping fully masked blocks.

- Optimized Computation via

torch.compile: The integration of torch.compile enables kernel fusion and efficient execution on GPUs by generating optimized Triton-based kernels. This efficiently parallelizes masked attention computations using optimized GPU execution paths.

This implementation exploits FlexAttention's ability to dynamically optimize execution based on the provided sparsity pattern. By precomputing block-level sparsity and leveraging efficient kernel fusion, it enables scalable attention computation for long sequences.

Overall, this approach provides a principled method to accelerate attention computations while preserving structured dependency constraints. End-to-end, replacing FlashAttention kernels using a custom mask with FlexAttention kernels leads to ≈15%\approx15\%≈15% speedup in a model forward pass. We use a single A5000 for L=1024L=1024L=1024 and batch size B=16B=16B=16.

C. Experimental Details

We closely follow the same training and evaluation setup as used by [7].

C.1 Datasets

We conduct experiments on two datasets: The One Billion Word Dataset (LM1B; [29]) and OpenWebText (OWT; [30]). Models trained on LM1B use the bert-base-uncased tokenizer and a context length of 128. We report perplexities on the test split of LM1B. Models trained on OWT use the GPT2 tokenizer [31] and a context length of 1024. Since OWT does not have a validation split, we leave the last 100k documents for validation.

In preparing LM1B examples, [7] pad each example to fit in the context length of L=128L=128L=128 tokens. Since most examples consist of only a single sentence, block diffusion modeling for larger block sizes L′>4L'>4L′>4 would not be useful for training. Instead, we concatenate and wrap sequences to a length of 128. As a result, we retrain our autoregressive baseline, SEDD, and MDLM on LM1B with wrapping.

Similarly for OWT, we do not pad or truncate sequences, but concatenate them and wrap them to a length of 1024 similar to LM1B. For unconditional generation experiments in Section 6.2, we wish to generate sequences longer than the context length seen during training. However, [7] inject beginning-of-sequence and end-of-sequence tokens ([BOS], [EOS] respectively) at the beginning and end of the training context. Thus, baselines from [7] will generate sequences that match the training context size. To examine model generations across varying lengths in Section 6.2, we retrain our AR, SEDD, and MDLM baselines without injecting [BOS] and [EOS] tokens in the examples. We also adopt this preprocessing convention for training all BD3-LMs on OWT.

C.2 Architecture

The model architecture augments the diffusion transformer ([71]) with rotary positional embeddings ([72]). We parameterize our autoregressive baselines, SEDD, MDLM, and BD3-LMs with a transformer architecture from [7] that uses 12 layers, a hidden dimension of 768, and 12 attention heads. This corresponds to 110M parameters. We do not include timestep conditioning as [7] show it does not affect performance. We use the AdamW optimizer with a batch size of 512 and constant learning rate warmup from 0 to 3e-4 for 2.5K gradient updates.

C.3 Training

We train a base BD3-LM using the maximum context length L′=LL'=LL′=L for 850K gradient steps. Then, we fine-tune under varying L′L'L′ using the noise schedule optimization for 150K gradient steps on the One Billion Words dataset (LM1B) and OpenWebText (OWT). This translates to 65B tokens and 73 epochs on LM1B, 524B tokens and 60 epochs on OWT. We use 3090, A5000, A6000, and A100 GPUs.

C.4 Likelihood Evaluation

We use a single Monte Carlo estimate for sampling ttt to evaluate the likelihood of a token block. We adopt a low-discrepancy sampler proposed in [27] that reduces the variance of this estimate by ensuring the time steps are more evenly spaced across the interval [0, 1] following [7]. In particular, we sample the time step for each block b∈{1,…,B}b \in \{1, \dots, B\}b∈{1,…,B} and sequence k∈{1,…,K}k \in \{1, \dots, K\}k∈{1,…,K} from a different partition of the uniform interval t(k,b)∼U[(k−1)B+b−1KB,(k−1)B+bKB]t(k, b) \sim \mathcal{U}[\frac{(k-1)B + b - 1}{KB}, \frac{(k-1)B + b}{KB}]t(k,b)∼U[KB(k−1)B+b−1,KB(k−1)B+b].

This low-discrepancy sampler is used for evaluation. For training, each masking probability may be sampled from a ``clipped" range 1−αt∼U[β,ω]1 - \alpha_{t} \sim \mathcal{U}[\beta, \omega]1−αt∼U[β,ω]. During training, we uniformly sample t∈[0,1]t \in [0, 1]t∈[0,1] under the low-discrepancy sampler. We then apply a linear interpolation to ensure that the masking probability is linear within the desired range: 1−αt=β+(ω−β)t1 - \alpha_{t} = \beta + (\omega - \beta) t1−αt=β+(ω−β)t.

When reporting zero-shot likelihoods on benchmark datasets from [31] using models trained on OWT, we wrap all sequences to 1024 tokens and do not add [EOS] between sequences following [7].

C.5 Inference

Generative Perplexity We report generative perplexity under GPT2-Large from models trained on OWT using a context length of 1024 tokens. Since GPT2-Large uses a context size of 1024, we compute the generative perplexity for samples longer than 1024 tokens using a sliding window with a stride length of 512 tokens.

Nucleus Sampling Following SSD-LM ([19]), we employ nucleus sampling for BD3-LMs and our baselines. For SSD-LM, we use their default hyperparameters p=0.95p=0.95p=0.95 for block size L′=25L'=25L′=25. For BD3-LMs, AR and MDLM, we use p=0.9p=0.9p=0.9. For SEDD, we find that p=0.99p=0.99p=0.99 works best.

Number of Diffusion Steps In Table 7, BD3-LMs and MDLM use T=5T=5T=5 K diffusion steps. BD3-LMs and MDLM use efficient sampling by caching the output of the denoising network as proposed by [7, 25], which ensures that the number of generation steps does not exceed the sample length LLL. Put simply, once a token is unmasked, it is never remasked as a result of the simplified denoising model (Suppl. Appendix B.3). We use MDLM's block-wise decoding algorithm for generating variable-length sequences, however these models are not trained with block diffusion. We adopt their default stride length of 512 tokens.

SSD-LM (first row in Table 7) and SEDD use T=1T=1T=1 K diffusion steps. Since block diffusion performs TTT diffusion steps for each block b∈{1,…,B}b \in \{ 1, \dots, B \}b∈{1,…,B}, SSD-LM undergoes BTBTBT generation steps. Thus to fairly compare with SSD-LM, we also report generative perplexity for T=25T=25T=25 diffusion steps so that the number of generation steps does not exceed the sequence length (second row in Table 7).

Improved Categorical Sampling of Diffusion Models We employ two improvements to Gumbel-based categorical sampling of diffusion models as proposed by [57].

First, we use the corrected Gumbel-based categorical sampling from [57] by sampling 64-bit Gumbel variables. Reducing the precision to 32-bit has been shown to significantly truncate the Gumbel variables, lowering the temperature and decreasing the sentence entropy.

Second, [57] show that the MDLM sampling time scales with the diffusion steps TTT, even though the number of generation steps is bounded by the sequence length. For sample length LLL and vocabulary size VVV, the sampler requires sampling O(TLV)\mathcal{O}(T L V)O(TLV) uniform variables and performing logarithmic operations on them.

We adopt the first-hitting sampler proposed by [57] that requires sampling O(LV)\mathcal{O}(L V)O(LV) uniform variables, and thus greatly improves sampling speed especially when T≫LT \gg LT≫L. The first-hitting sampler is theoretically equivalent to the MDLM sampler and leverages two observations: (1) the transition probability is independent of the denoising network, (2) the transition probability is the same for all masked tokens for a given ttt. Thus, the first timestep where a token is unmasked can be analytically sampled as follows (assuming a linear schedule where αt=1−t\alpha_{t} = 1 - tαt=1−t):

where n∈{L,…,1}n \in \{ L, \dots, 1\}n∈{L,…,1} denotes the number of masked tokens, un∼U[0,1]u_n \sim \mathcal{U}[0, 1]un∼U[0,1] and tn−1t_{n-1}tn−1 corresponds to the first timestep where n−1n-1n−1 tokens are masked.

Variable-Length Sequence Generation For arbitrary-length sequence generation using BD3-LMs and AR in Table 6, we continue to sample tokens until the following stopping criteria are met:

- an [EOS] token is sampled

- the average entropy of the the last 256-token chunk is below 4

where criterion 2 are necessary to prevent run-on samples from compounding errors (for example, a sequence of repeating tokens). We find that degenerate samples with low entropy result in significantly low perplexities under GPT2 and lower the reported generative perplexity. Thus, when a sample meets criterion 2, we regenerate the sample when reporting generative perplexity in Table 7.

D. Samples

References

[1] Jonathan Ho, Ajay Jain, and Pieter Abbeel. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33:6840–6851, 2020.

[3] Subham Sekhar Sahoo, Aaron Gokaslan, Christopher De Sa, and Volodymyr Kuleshov. Diffusion models with learned adaptive noise. In

The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2024b. URL

https://openreview.net/forum?id=loMa99A4p8[4] Jonathan Ho, Tim Salimans, Alexey Gritsenko, William Chan, Mohammad Norouzi, and David J Fleet. Video diffusion models. arXiv:2204.03458, 2022.

[5] Agrim Gupta, Lijun Yu, Kihyuk Sohn, Xiuye Gu, Meera Hahn, Li Fei-Fei, Irfan Essa, Lu Jiang, and Jose Lezama. Photorealistic video generation with diffusion models, 2023. URL

https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.06662[6] Aaron Lou, Chenlin Meng, and Stefano Ermon. Discrete diffusion modeling by estimating the ratios of the data distribution. In

Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024. URL

https://openreview.net/forum?id=CNicRIVIPA[7] Subham Sekhar Sahoo, Marianne Arriola, Aaron Gokaslan, Edgar Mariano Marroquin, Alexander M Rush, Yair Schiff, Justin T Chiu, and Volodymyr Kuleshov. Simple and effective masked diffusion language models. In

The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2024a. URL

https://openreview.net/forum?id=L4uaAR4ArM[8] Pavel Avdeyev, Chenlai Shi, Yuhao Tan, Kseniia Dudnyk, and Jian Zhou. Dirichlet diffusion score model for biological sequence generation. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp.\ 1276–1301. PMLR, 2023.

[9] Shrey Goel, Vishrut Thoutam, Edgar Mariano Marroquin, Aaron Gokaslan, Arash Firouzbakht, Sophia Vincoff, Volodymyr Kuleshov, Huong T Kratochvil, and Pranam Chatterjee. Memdlm: De novo membrane protein design with masked discrete diffusion protein language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.16735, 2024.

[10] Yair Schiff, Subham Sekhar Sahoo, Hao Phung, Guanghan Wang, Sam Boshar, Hugo Dalla-torre, Bernardo P de Almeida, Alexander Rush, Thomas Pierrot, and Volodymyr Kuleshov. Simple guidance mechanisms for discrete diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.10193, 2024.

[11] Hunter Nisonoff, Junhao Xiong, Stephan Allenspach, and Jennifer Listgarten. Unlocking guidance for discrete state-space diffusion and flow models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.01572, 2024.

[12] Xiner Li, Yulai Zhao, Chenyu Wang, Gabriele Scalia, Gokcen Eraslan, Surag Nair, Tommaso Biancalani, Shuiwang Ji, Aviv Regev, Sergey Levine, et al. Derivative-free guidance in continuous and discrete diffusion models with soft value-based decoding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08252, 2024.

[13] Subham Sekhar Sahoo, John Xavier Morris, Aaron Gokaslan, Srijeeta Biswas, Vitaly Shmatikov, and Volodymyr Kuleshov. Zero-order diffusion guidance for inverse problems, 2024c. URL

https://openreview.net/forum?id=JBgBrnhLLL[14] Jacob Austin, Daniel D Johnson, Jonathan Ho, Daniel Tarlow, and Rianne Van Den Berg. Structured denoising diffusion models in discrete state-spaces. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34:17981–17993, 2021.

[15] Daniel Israel, Aditya Grover, and Guy Van den Broeck. Enabling autoregressive models to fill in masked tokens. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.06901, 2025.

[16] Ishaan Gulrajani and Tatsunori B Hashimoto. Likelihood-based diffusion language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36, 2024.

[17] Phillip Si, Allan Bishop, and Volodymyr Kuleshov. Autoregressive quantile flows for predictive uncertainty estimation. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022.

[18] Phillip Si, Zeyi Chen, Subham Sekhar Sahoo, Yair Schiff, and Volodymyr Kuleshov. Semi-autoregressive energy flows: exploring likelihood-free training of normalizing flows. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp.\ 31732–31753. PMLR, 2023.

[19] Xiaochuang Han, Sachin Kumar, and Yulia Tsvetkov. Ssd-lm: Semi-autoregressive simplex-based diffusion language model for text generation and modular control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.17432, 2022.

[20] Xiaochuang Han, Sachin Kumar, Yulia Tsvetkov, and Marjan Ghazvininejad. David helps goliath: Inference-time collaboration between small specialized and large general diffusion lms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14771, 2023.

[21] Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, Eric Weiss, Niru Maheswaranathan, and Surya Ganguli. Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics. In International conference on machine learning, pp.\ 2256–2265. PMLR, 2015.

[22] Yang Song and Stefano Ermon. Generative modeling by estimating gradients of the data distribution. Advances in neural information processing systems, 32, 2019.

[23] Haoran Sun, Lijun Yu, Bo Dai, Dale Schuurmans, and Hanjun Dai. Score-based continuous-time discrete diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.16750, 2022.

[24] Jiaxin Shi, Kehang Han, Zhe Wang, Arnaud Doucet, and Michalis Titsias. Simplified and generalized masked diffusion for discrete data. In

The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2024. URL

https://openreview.net/forum?id=xcqSOfHt4g[25] Jingyang Ou, Shen Nie, Kaiwen Xue, Fengqi Zhu, Jiacheng Sun, Zhenguo Li, and Chongxuan Li. Your absorbing discrete diffusion secretly models the conditional distributions of clean data. In

The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2025. URL

https://openreview.net/forum?id=sMyXP8Tanm[26] Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

[27] Diederik Kingma, Tim Salimans, Ben Poole, and Jonathan Ho. Variational diffusion models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:21696–21707, 2021.

[28] Zihang Dai, Zhilin Yang, Yiming Yang, Jaime Carbonell, Quoc V Le, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. Transformer-xl: Attentive language models beyond a fixed-length context. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.02860, 2019.

[29] Ciprian Chelba, Tomas Mikolov, Mike Schuster, Qi Ge, Thorsten Brants, Phillipp Koehn, and Tony Robinson. One billion word benchmark for measuring progress in statistical language modeling, 2014.

[31] Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, Ilya Sutskever, et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog, 1(8):9, 2019.

[32] Mitch Marcus, Beatrice Santorini, and Mary Ann Marcinkiewicz. Building a large annotated corpus of english: The penn treebank. Computational linguistics, 19(2):313–330, 1993.

[33] Stephen Merity, Caiming Xiong, James Bradbury, and Richard Socher. Pointer sentinel mixture models, 2016.

[34] Denis Paperno, Germán Kruszewski, Angeliki Lazaridou, Ngoc Quan Pham, Raffaella Bernardi, Sandro Pezzelle, Marco Baroni, Gemma Boleda, and Raquel Fernandez. The LAMBADA dataset: Word prediction requiring a broad discourse context. In

Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pp.\ 1525–1534, Berlin, Germany, August 2016. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL

http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P16-1144[35] Xiang Zhang, Junbo Jake Zhao, and Yann LeCun. Character-level convolutional networks for text classification. In NIPS, 2015.

[36] Arman Cohan, Franck Dernoncourt, Doo Soon Kim, Trung Bui, Seokhwan Kim, Walter Chang, and Nazli Goharian. A discourse-aware attention model for abstractive summarization of long documents.

Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers), 2018. doi:10.18653/v1/n18-2097. URL

http://dx.doi.org/10.18653/v1/n18-2097[37] Huiwen Chang, Han Zhang, Lu Jiang, Ce Liu, and William T Freeman. Maskgit: Masked generative image transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp.\ 11315–11325, 2022.

[38] Tri Dao, Dan Fu, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. Flashattention: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with io-awareness. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:16344–16359, 2022.

[39] Juechu Dong, Boyuan Feng, Driss Guessous, Yanbo Liang, and Horace He. Flex attention: A programming model for generating optimized attention kernels. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.05496, 2024.

[40] Zhengfu He, Tianxiang Sun, Kuanning Wang, Xuanjing Huang, and Xipeng Qiu. Diffusionbert: Improving generative masked language models with diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.15029, 2022.

[41] Andrew Campbell, Joe Benton, Valentin De Bortoli, Thomas Rainforth, George Deligiannidis, and Arnaud Doucet. A continuous time framework for discrete denoising models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:28266–28279, 2022.

[42] Xiang Li, John Thickstun, Ishaan Gulrajani, Percy S Liang, and Tatsunori B Hashimoto. Diffusion-lm improves controllable text generation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:4328–4343, 2022.

[43] Sander Dieleman, Laurent Sartran, Arman Roshannai, Nikolay Savinov, Yaroslav Ganin, Pierre H Richemond, Arnaud Doucet, Robin Strudel, Chris Dyer, Conor Durkan, et al. Continuous diffusion for categorical data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.15089, 2022.

[44] Ting Chen, Ruixiang Zhang, and Geoffrey Hinton. Analog bits: Generating discrete data using diffusion models with self-conditioning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.04202, 2022.

[45] Jiaming Song, Chenlin Meng, and Stefano Ermon. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02502, 2020.

[46] Jonathan Ho and Tim Salimans. Classifier-free diffusion guidance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.12598, 2022.

[47] Alex Graves, Rupesh Kumar Srivastava, Timothy Atkinson, and Faustino Gomez. Bayesian flow networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.07037, 2023.

[48] Tong Wu, Zhihao Fan, Xiao Liu, Hai-Tao Zheng, Yeyun Gong, yelong shen, Jian Jiao, Juntao Li, zhongyu wei, Jian Guo, Nan Duan, and Weizhu Chen. AR-diffusion: Auto-regressive diffusion model for text generation. In

Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023. URL

https://openreview.net/forum?id=0EG6qUQ4xE[49] Boyuan Chen, Diego Mart'ı Monsó, Yilun Du, Max Simchowitz, Russ Tedrake, and Vincent Sitzmann. Diffusion forcing: Next-token prediction meets full-sequence diffusion. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37:24081–24125, 2025.

[50] Jiacheng Ye, Shansan Gong, Liheng Chen, Lin Zheng, Jiahui Gao, Han Shi, Chuan Wu, Xin Jiang, Zhenguo Li, Wei Bi, et al. Diffusion of thoughts: Chain-of-thought reasoning in diffusion language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.07754, 2024.

[51] Shibo Hao, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, DiJia Su, Xian Li, Zhiting Hu, Jason Weston, and Yuandong Tian. Training large language models to reason in a continuous latent space. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.06769, 2024.

[52] Deqian Kong, Minglu Zhao, Dehong Xu, Bo Pang, Shu Wang, Edouardo Honig, Zhangzhang Si, Chuan Li, Jianwen Xie, Sirui Xie, et al. Scalable language models with posterior inference of latent thought vectors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.01567, 2025.

[53] Lingxiao Zhao, Xueying Ding, and Leman Akoglu. Pard: Permutation-invariant autoregressive diffusion for graph generation. In

The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2024. URL

https://openreview.net/forum?id=x4Kk4FxLs3[54] Emiel Hoogeboom, Didrik Nielsen, Priyank Jaini, Patrick Forré, and Max Welling. Argmax flows and multinomial diffusion: Learning categorical distributions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34:12454–12465, 2021b.

[55] Emiel Hoogeboom, Alexey A Gritsenko, Jasmijn Bastings, Ben Poole, Rianne van den Berg, and Tim Salimans. Autoregressive diffusion models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.02037, 2021a.

[56] Benigno Uria, Iain Murray, and Hugo Larochelle. A deep and tractable density estimator. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp.\ 467–475. PMLR, 2014.

[57] Kaiwen Zheng, Yongxin Chen, Hanzi Mao, Ming-Yu Liu, Jun Zhu, and Qinsheng Zhang. Masked diffusion models are secretly time-agnostic masked models and exploit inaccurate categorical sampling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.02908, 2024.

[58] Jiatao Gu, Changhan Wang, and Junbo Zhao. Levenshtein transformer. Advances in neural information processing systems, 32, 2019.

[59] Jiatao Gu, James Bradbury, Caiming Xiong, Victor OK Li, and Richard Socher. Non-autoregressive neural machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.02281, 2017.