Mathematical exploration and discovery at scale

Bogdan Georgiev, Javier Gómez-Serrano, Terence Tao, Adam Zsolt Wagner

Department of Mathematics, Brown University, 314 Kassar House, 151 Thayer St., Providence, RI 02912, USA

Institute for Advanced Study, 1 Einstein Drive, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA

[email protected]

Institute for Advanced Study, 1 Einstein Drive, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA

[email protected]

Abstract

AlphaEvolve [1] is a generic evolutionary coding agent that combines the generative capabilities of LLMs with automated evaluation in an iterative evolutionary framework that proposes, tests, and refines algorithmic solutions to challenging scientific and practical problems. In this paper we showcase AlphaEvolve as a tool for autonomously discovering novel mathematical constructions and advancing our understanding of long-standing open problems.To demonstrate its breadth, we considered a list of 67 problems spanning mathematical analysis, combinatorics, geometry, and number theory. The system rediscovered the best known solutions in most of the cases and discovered improved solutions in several. In some instances,

AlphaEvolve is also able to generalize results for a finite number of input values into a formula valid for all input values. Furthermore, we are able to combine this methodology with Deep Think [2] and AlphaProof [3] in a broader framework where the additional proof-assistants and reasoning systems provide automated proof generation and further mathematical insights.These results demonstrate that large language model-guided evolutionary search can autonomously discover mathematical constructions that complement human intuition, at times matching or even improving the best known results, highlighting the potential for significant new ways of interaction between mathematicians and AI systems. We present

AlphaEvolve as a powerful new tool for mathematical discovery, capable of exploring vast search spaces to solve complex optimization problems at scale, often with significantly reduced requirements on preparation and computation time.1. Introduction

The landscape of mathematical discovery has been fundamentally transformed by the emergence of computational tools that can autonomously explore mathematical spaces and generate novel constructions [4,5,6,7].

AlphaEvolve represents a step in this evolution, demonstrating that large language models, when combined with evolutionary computation and rigorous automated evaluation, can discover explicit constructions that either match or improve upon the best-known bounds to long-standing mathematical problems, at large scales.AlphaEvolve is not a general-purpose solver for all types of mathematical problems; it is primarily designed to attack problems in which a key objective is to construct a complex mathematical object that satisfies good quantitative properties, such as obeying a certain inequality with a good numerical constant. In this paper, we report on our experiments testing the performance of AlphaEvolve on a wide variety of such problems, primarily in the areas of analysis, combinatorics, and geometry. In many cases, the constructions provided by AlphaEvolve were not merely numerical in nature, but can be interpreted and generalized by human mathematicians, by other tools such as Deep Think, and even by AlphaEvolve itself. AlphaEvolve was not able to match or exceed previous results in all cases, and some of the individual improvements it was able to achieve could likely also have been matched by more traditional computational or theoretical methods performed by human experts. However, in contrast to such methods, we have found that AlphaEvolve can be readily scaled up to study large classes of problems at a time, without requiring extensive expert supervision for each new problem. This demonstrates that evolutionary computational approaches can systematically explore the space of mathematical objects in ways that complement traditional techniques, thus helping answer questions about the relationship between computational search and mathematical existence proofs.We have also seen that in many cases, besides the scaling, in order to get

AlphaEvolve to output comparable results to the literature and in contrast to traditional ways of doing mathematics, very little overhead is needed: on average the usual preparation time for the setup of a problem using AlphaEvolve took only up to a few hours. We expect that without prior knowledge, information or code, an equivalent traditional setup would typically take significantly longer. This has led us to use the term constructive mathematics at scale.A crucial mathematical insight underlying

AlphaEvolve's effectiveness is its ability to operate across multiple levels of abstraction simultaneously. The system can optimize not just the specific parameters of a mathematical construction, but also the algorithmic strategy for discovering such constructions. This meta-level evolution represents a new form of recursion where the optimization process itself becomes the object of optimization. For example, AlphaEvolve might evolve a program that uses a set of heuristics, a SAT solver, a second order method without convergence guarantee, or combinations of them. This hierarchical approach is particularly evident in AlphaEvolve's treatment of complex mathematical problems (suggested by the user), where the system often discovers specialized search heuristics for different phases of the optimization process. Early-stage heuristics excel at making large improvements from random or simple initial states, while later-stage heuristics focus on fine-tuning near-optimal configurations. This emergent specialization mirrors the intuitive approaches employed by human mathematicians.1.1 Comparison with [1].

Some details of our results were already mentioned in [1]. The purpose of that white paper was to introduce

AlphaEvolve and highlight its general broad applicability. While the paper discussed impact and some usage in the context of mathematics, we have here expanded on the list of considered problems in terms of their breadth, hardness and importance. We now give full details for all of them. The problems below are arranged in no particular order. For reasons of space, we do not attempt to exhaustively survey the history of each of the problems listed here, and refer the reader to the references provided for each problem for a more in-depth discussion of known results.Along with this paper, we will also release a live Repository of Problems with code containing some experiments and extended details of the problems. While the presence of randomness in the evolution process may make reproducibility harder, we expect our results to be fully reproducible with the information given and enough experiments.

1.2 AI and Mathematical Discovery

The emergence of artificial intelligence as a transformative force in mathematical discovery has marked a paradigm shift in how we approach some of mathematics' most challenging problems. Recent breakthroughs [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] have demonstrated AI's capability to assist mathematicians.

AlphaGeometry solved 25 out of 30 Olympiad geometry problems within standard time limits [16]. AlphaProof and AlphaGeometry 2 [3] achieved silver-medal performance at the 2024 International Mathematical Olympiad followed by a gold-medal performance of an advanced Gemini Deep Think framework at the 2025 International Mathematical Olympiad [2]. See [17] for a gold-medal performance by a model from OpenAI. Beyond competition performance, AI has begun making genuine mathematical discoveries, as demonstrated by FunSearch [6], discovering new solutions to the cap set problem and more effective bin-packing algorithms (see also [18]), or PatternBoost [4] disproving a 30-year old conjecture (see also [7]), or precursors such as Graffiti [19] generating conjectures. Other instances of AI helping mathematicians are for example [20,21,22,23], in the context of finding formal and informal proofs of mathematical statements. While AlphaEvolve is geared more towards exploration and discovery, we have been able to pipeline it with other systems in a way that allows us not only to explore but also to combine our findings with a mathematically rigorous proof as well as a formalization of it.1.3 Evolving Algorithms to Find Constructions

At its core,

AlphaEvolve is a sophisticated search algorithm. To understand its design, it is helpful to start with a familiar idea: local search. To solve a problem like finding a graph on 50 vertices with no triangles and no cycles of length four, and the maximum number of edges, a standard approach would be to start with a random graph, and then iteratively make small changes (e.g., adding or removing an edge) that improve its score (in this case, the edge count, penalized for any triangles or four-cycles). We keep 'hill-climbing' until we can no longer improve.The first key idea, inherited from

AlphaEvolve's predecessor, FunSearch [6] (see Table 1 for a head to head comparison) and its reimplementation [18], is to perform this local search not in the space of graphs, but in the space of Python programs that generate graphs. We start with a simple program, then use a large language model (LLM) to generate many similar but slightly different programs ('mutations'). We score each program by running it and evaluating the graph it produces. It is natural to wonder why this approach would be beneficial. An LLM call is usually vastly more expensive than adding an edge or evaluating a graph, so this way we can often explore thousands or even millions of times fewer candidates than with standard local search methods. Many 'nice' mathematical objects, like the optimal Hoffman-Singleton graph for the aforementioned problem [24], have short, elegant descriptions as code. Moreover even if there is only one optimal construction for a problem, there can be many different, natural programs that generate it. Conversely, the countless 'ugly' graphs that are local optima might not correspond to any simple program. Searching in program space might act as a powerful prior for simplicity and structure, helping us navigate away from messy local maxima towards elegant, often optimal, solutions. In the case where the optimal solution does not admit a simple description, even by a program, and the best way to find it is via heuristic methods, we have found that AlphaEvolve excels at this task as well.Still, for problems where the scoring function is cheap to compute, the sheer brute-force advantage of traditional methods can be hard to overcome. Our proposed solution to this problem is as follows. Instead of evolving programs that directly generate a construction,

AlphaEvolve evolves programs that search for a construction. This is what we refer to as the search mode of AlphaEvolve, and it was the standard mode we used for all the problems where the goal was to find good constructions, and we did not care about their interpretability and generalizability.Each program in

AlphaEvolve's population is a search heuristic. It is given a fixed time budget (say, 100 seconds) and tasked with finding the best possible construction within that time. The score of the heuristic is the score of the best object it finds. This resolves the speed disparity: a single, slow LLM call to generate a new search heuristic can trigger a massive cheap computation, where that heuristic explores millions of candidate constructions on its own.We emphasize that the search does not have to start from scratch each time. Instead, a new heuristic is evaluated on its ability to improve the best construction found so far. We are thus evolving a population of 'improver' functions. This creates a dynamic, adaptive search process. In the beginning, heuristics that perform broad, exploratory searches might be favored. As we get closer to a good solution, heuristics that perform clever, problem-specific refinements might take over. The final result is often a sequence of specialized heuristics that, when chained together, produce a state-of-the-art construction. The downside is a potential loss of interpretability in the search process, but the final object it discovers remains a well-defined mathematical entity for us to study. This addition seems to be particularly useful for more difficult problems, where a single search function may not be able to discover a good solution by itself.

1.4 Generalizing from Examples to Formulas: the generalizer mode

Beyond finding constructions for a fixed problem size (e.g., packing for ) on which the above search mode excelled, we have experimented with a more ambitious generalizer mode. Here, we tasked

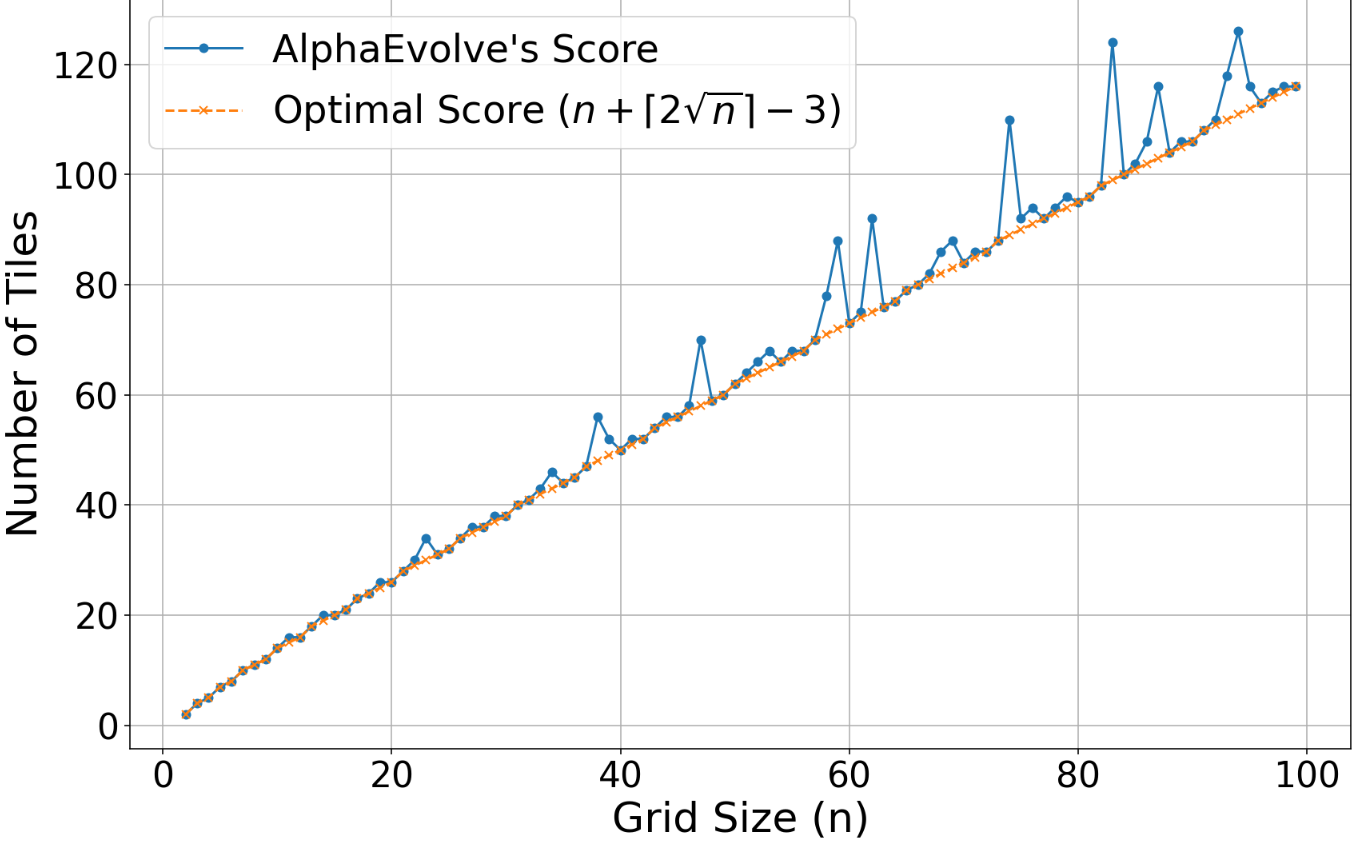

AlphaEvolve with writing a program that can solve the problem for any given . We evaluate the program based on its performance across a range of values. The hope is that by seeing its own (often optimal) solutions for small , AlphaEvolve can spot a pattern and generalize it into a construction that works for all .This mode is more challenging, but it has produced some of our most exciting results. In one case,

AlphaEvolve's proposed construction for the Nikodym problem (see Problem 1) inspired a new paper by the third author [25]. On the other hand, when using the search mode, the evolved programs can not easily be interpreted. Still, the final constructions themselves can be analyzed, and in the case of the artihmetic Kakeya problem (Problem 30) they inspired another paper by the third author [26].1.5 Building a pipeline of several AI tools

Even more strikingly, for the finite field Kakeya problem (cf. Problem 1),

AlphaEvolve discovered an interesting general construction. When we fed this programmatic solution to the agent called Deep Think [2], it successfully derived a proof of its correctness and a closed-form formula for its size. This proof was then fully formalized in the Lean proof assistant using another AI tool, AlphaProof [3]. This workflow, combining pattern discovery (AlphaEvolve), symbolic proof generation (Deep Think), and formal verification (AlphaProof), serves as a concrete example of how specialized AI systems can be integrated. It suggests a future potential methodology where a combination of AI tools can assist in the process of moving from an empirically observed pattern (suggested by the model) to a formally verified mathematical result, fully automated or semi-automated.1.6 Limitations

We would also like to point out that while

AlphaEvolve excels at problems that can be clearly formulated as the optimization of a smooth score function that is possible to 'hill-climbing' on, it sometimes struggles otherwise. In particular, we have encountered several instances where AlphaEvolve failed to attain an optimal or close to optimal result. We also report these cases below. In general, we have found AlphaEvolve most effective when applied at a large scale across a broad portfolio of loosely related problems such as, for example, packing problems or Sendov's conjecture and its variants.In Section 6, we will detail the new mathematical results discovered with this approach, along with all the examples we found where

AlphaEvolve did not manage to find the previously best known construction. We hope that this work will not only provide new insights into these specific problems but also inspire other scientists to explore how these tools can be adapted to their own areas of research.2. General Description of AlphaEvolve and Usage

As introduced in [1],

AlphaEvolve establishes a framework that combines the creativity of LLMs with automated evaluators. Some of its description and usage appears there and we discuss it here in order for this paper to be self-contained. At its heart, AlphaEvolve is an evolutionary system. The system maintains a population of programs, each encoding a potential solution to a given problem. This population is iteratively improved through a loop that mimics natural selection.The evolutionary process consists of two main components:

- A Generator (LLM): This component is responsible for introducing variation. It takes some of the better-performing programs from the current population and 'mutates' them to create new candidate solutions. This process can be parallelized across several CPUs. By leveraging an LLM, these mutations are not random character flips but intelligent, syntactically-aware modifications to the code, inspired by the logic of the parent programs and the expert advice given by the human user.

- An Evaluator (typically provided by the user): This is the 'fitness function'. It is a deterministic piece of code that takes a program from the population, runs it, and assigns it a numerical score based on its performance. For a mathematical construction problem, this score could be how well the construction satisfies certain properties (e.g., the number of edges in a graph, or the density of a packing).

The process begins with a few simple initial programs. In each generation, some of the better-scoring programs are selected and fed to the LLM to generate new, potentially better, offspring. These offspring are then evaluated, scored, and the higher scoring ones among them will form the basis of the future programs. This cycle of generation and selection allows the population to

evolve over time towards programs that produce increasingly high-quality solutions. Note that since every evaluator has a fixed time budget, the total CPU hours spent by the evaluators is directly proportional to the total number of LLM calls made in the experiment. For more details and applications beyond mathematical problems, we refer the reader to [1]. For further applications and improvements of AlphaEvolve to MAX-CUT, MAX- -CUT and MAX-Independent Set problems see [27]. After AlphaEvolve was released, other open-source implementations of frameworks leveraging LLMs for scientific discovery were developed such as OpenEvolve [28], ShinkaEvolve [29] or DeepEvolve [30].When applied to mathematics, this framework is particularly powerful for finding constructions with extremal properties. As described in the introduction, we primarily use it in a search mode, where the programs being evolved are not direct constructions but are themselves heuristic search algorithms. The evaluator gives one of these evolved heuristics a fixed time budget and scores it based on the quality of the best construction it can find in that time. This method turns the expensive, creative power of the LLM towards designing efficient search strategies, which can then be executed cheaply and at scale. This allows

AlphaEvolve to effectively navigate vast and complex mathematical landscapes, discovering the novel constructions we detail in this paper.3. Meta-Analysis and Ablations

To better understand the behavior and sensitivities of

AlphaEvolve, we conducted a series of meta-analyses and ablation studies. These experiments are designed to answer practical questions about the method: How do computational resources affect the search? What is the role of the underlying LLM? What are the typical costs involved? For consistency, many of these experiments use the autocorrelation inequality (Problem 2) as a testbed, as it provides a clean, fast-to-evaluate objective.3.1 The Trade-off Between Speed of Discovery and Evaluation Cost

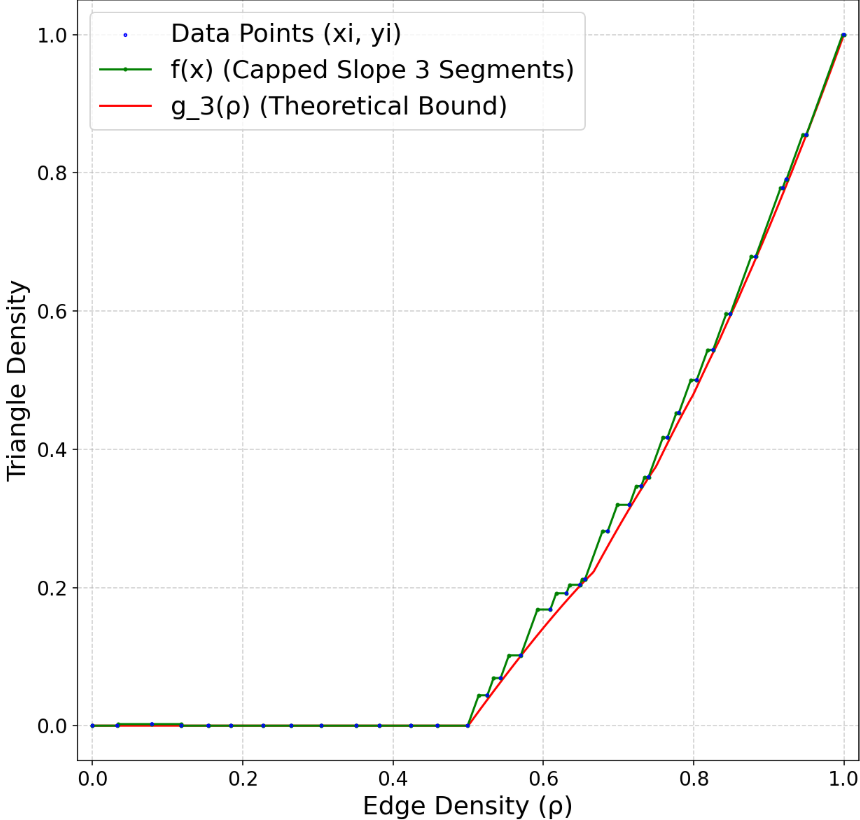

A key parameter in any

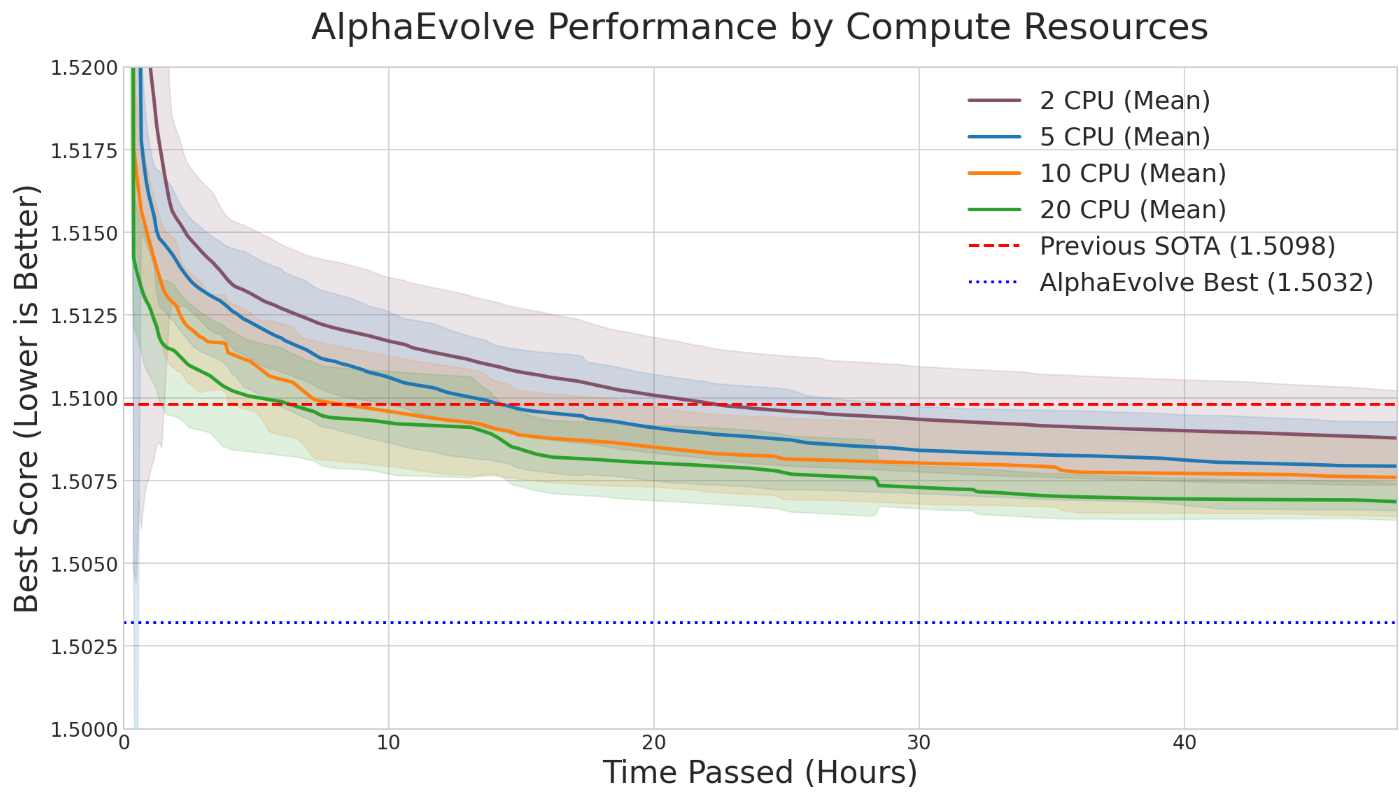

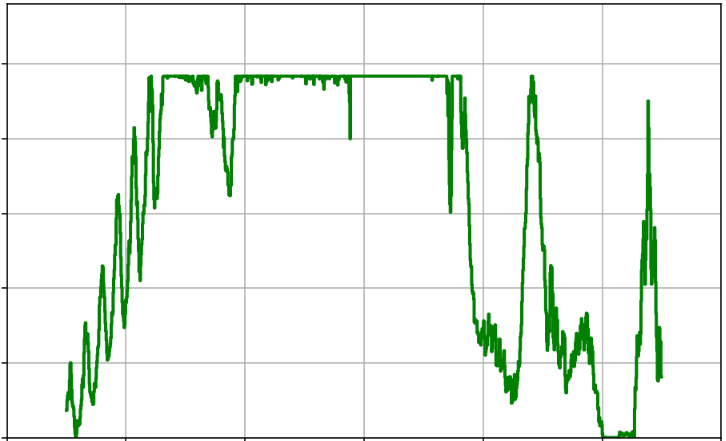

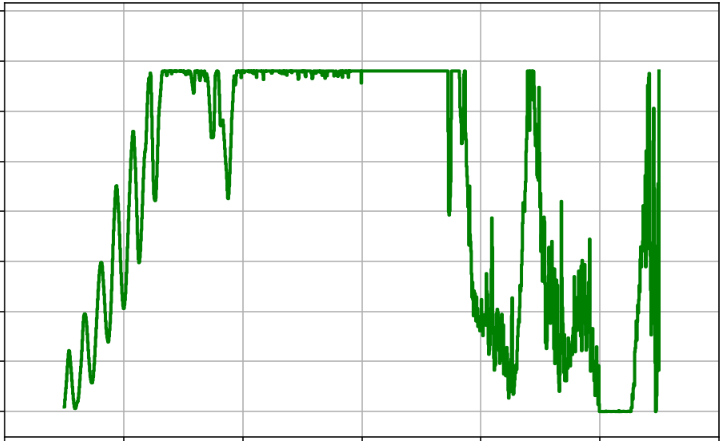

AlphaEvolve run is the amount of parallel computation used (e.g., the number of CPU threads). Intuitively, more parallelism should lead to faster discoveries. We investigated this by running Problem 2 with varying numbers of parallel threads (from 2 up to 20).Our findings (see Figure 2), while noisy, seem to align with this expected trade-off. Increasing the number of parallel threads significantly accelerated the time-to-discovery. Runs with 20 threads consistently surpassed the state-of-the-art bound much faster than those with 2 threads. However, this speed comes at a higher total cost. Since each thread operates semi-independently and makes its own calls to the LLM to generate new heuristics, doubling the threads roughly doubles the rate of LLM queries. Even though the threads communicate with each other and build upon each other's best constructions, achieving the result faster requires a greater total number of LLM calls. The optimal strategy depends on the researcher's priority: for rapid exploration, high parallelism is effective; for minimizing direct costs, fewer threads over a longer period is the more economical choice.

3.2 The Role of Model Choice: Large vs. Cheap LLMs

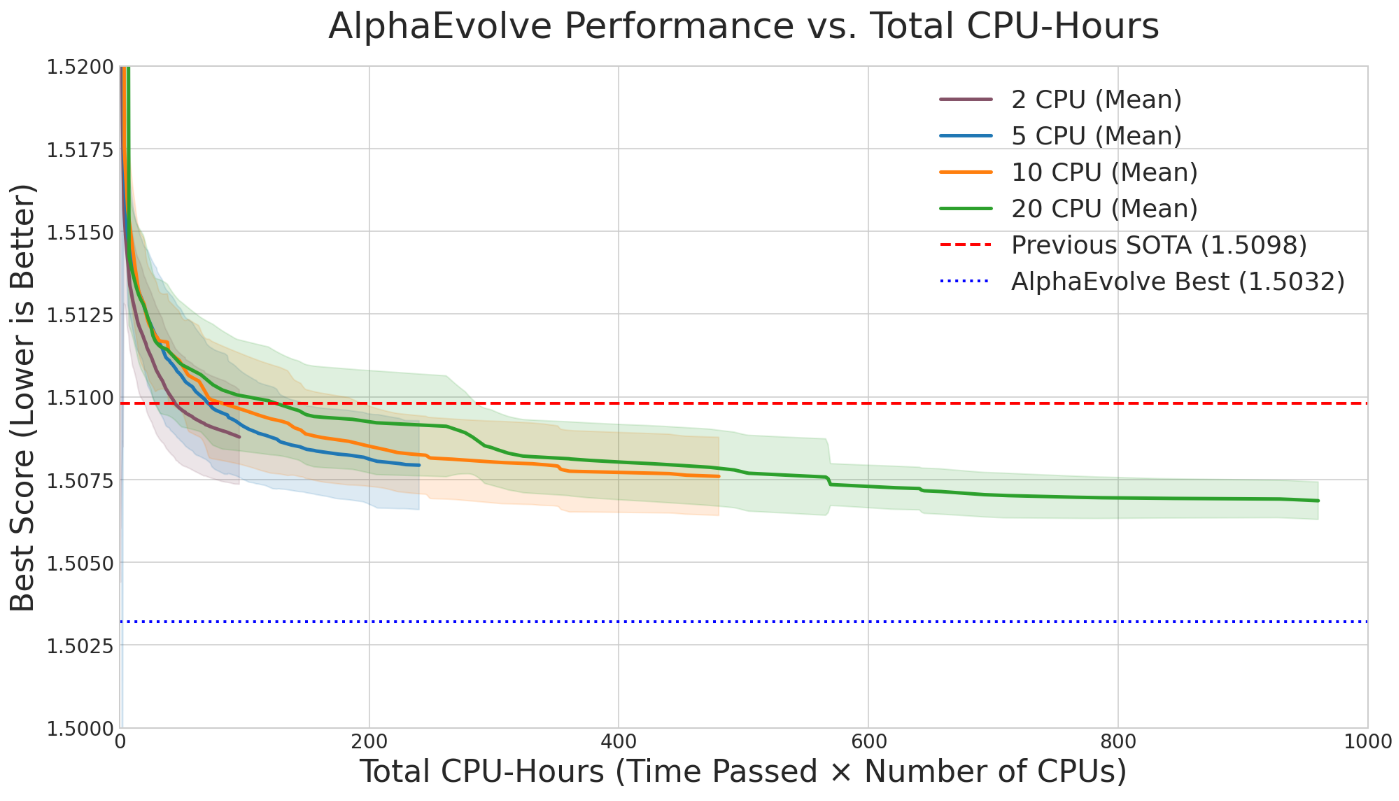

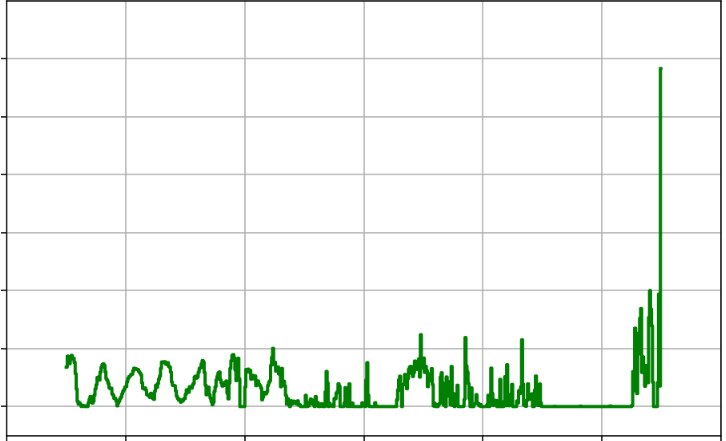

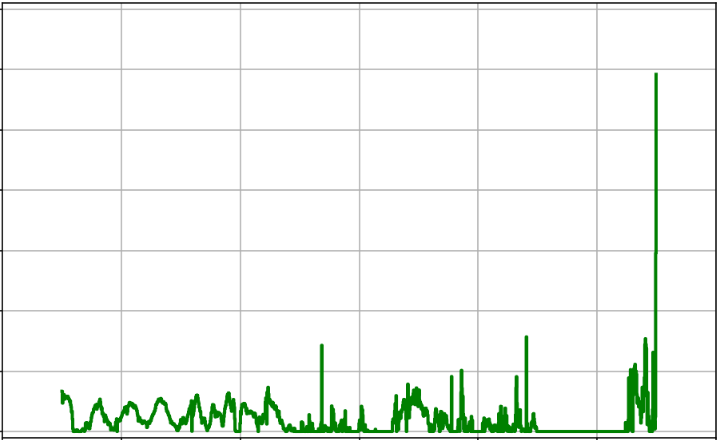

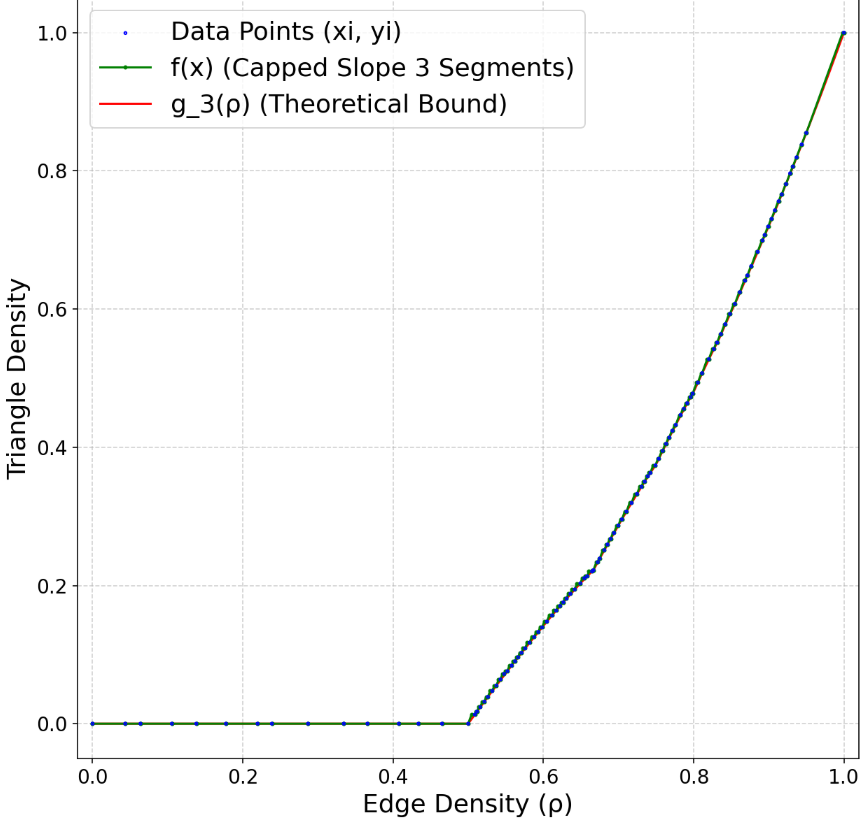

AlphaEvolve's performance is fundamentally tied to the LLM used for generating code mutations. We compared the effectiveness of a high-performance LLM against a much smaller, cheaper model (with a price difference of roughly 15x per input token and 30x per output token).

We observed that the more capable LLM tends to produce higher-quality suggestions (see Figure 3), often leading to better scores with fewer evolutionary steps. However, the most effective strategy was not always to use the most powerful model exclusively. For this simple autocorrelation problem, the most cost-effective strategy to beat the literature bound was to use the cheapest model across many runs. The total LLM cost for this was remarkably low: a few USD. However, for the more difficult problem of Nikodym sets (see Problem ), the cheap model was not able to get the most elaborate constructions.

We also observed that an experiment using only high-end models can sometimes perform worse than a run that occasionally used cheaper models as well. One explanation for this is that different models might suggest very different approaches, and even though a worse model generally suggests lower quality ideas, it does add variance. This suggests a potential benefit to injecting a degree of randomness or "naive creativity" into the evolutionary process. We suspect that for problems requiring deeper mathematical insight, the value of the smarter LLM would become more pronounced, but for many optimization landscapes, diversity from cheaper models is a powerful and economical tool.

4. Conclusions

Our exploration of

AlphaEvolve has yielded several key insights, which are summarized below. We have found that the selection of the verifier is a critical component that significantly influences the system's performance and the quality of the discovered results. For example, sometimes the optimizer will be drawn more towards more stable (trivial) solutions which we want to avoid. Designing a clever verifier that avoids this behavior is key to discover new results.Similarly, employing continuous (as opposed to discrete) loss functions proved to be a more effective strategy for guiding the evolutionary search process in some cases. For example, for Problem 53 we could have designed our scoring function as the number of touching cylinders of any given configuration (or if the configuration is illegal). By looking at a continuous scoring function depending on the distances led to a more successful and faster optimization process.

During our experiments, we also observed a "cheating phenomenon", where the system would find loopholes or exploit artifacts (leaky verifier when approximating global constraints such as positivity by discrete versions of them, unreliable LLM queries to cheap models, etc.) in the problem setup rather than genuine solutions, highlighting the need for carefully designed and robust evaluation environments.

Another important component is the advice given in the prompt and the experience of the prompter. We have found that we got better at knowing how to prompt

AlphaEvolve the more we tried. For example, prompting as in our search mode versus trying to find the construction directly resulted in more efficient programs and much better results in the former case. Moreover, in the hands of a user who is a subject expert in the particular problem that is being attempted, AlphaEvolve has always performed much better than in the hands of another user who is not a subject expert: we have found that the advice one gives to AlphaEvolve in the prompt has a significant impact on the quality of the final construction. Giving AlphaEvolve an insightful piece of expert advice in the prompt almost always led to significantly better results: indeed, AlphaEvolve will always simply try to squeeze the most out of the advice it was given, while retaining the gist of the original advice. We stress that we think that, in general, it was the combination of human expertise and the computational capabilities of AlphaEvolve that led to the best results overall.An interesting finding for promoting the discovery of broadly applicable algorithms is that generalization improves when the system is provided with a more constrained set of inputs or features. Having access to a large amount of data does not necessarily imply better generalization performance. Instead, when we were looking for interpretable programs that generalize across a wide range of the parameters, we constrained

AlphaEvolve to have access to less data by showing it the previous best solutions only for small values of (see for example Problems 29, Problem 64, Problem 1). This "less is more" approach appears to encourage the emergence of more fundamental ideas. Looking ahead, a significant step toward greater autonomy for the system would be to enable AlphaEvolve to select its own hyperparameters, adapting its search strategy dynamically.Results are also significantly improved when the system is trained on correlated problems or a family of related problem instances within a single experiment. For example, when exploring geometric problems, tackling configurations with various numbers of points and dimensions simultaneously is highly effective. A search heuristic that performs well for a specific pair will likely be a strong foundation for others, guiding the system toward more universal principles.

We have found that

AlphaEvolve excels at discovering constructions that were already within reach of current mathematics, but had not yet been discovered due to the amount of time and effort required to find the right combination of standard ideas that works well for a particular problem. On the other hand, for problems where genuinely new, deep insights are required to make progress, AlphaEvolve is likely not the right tool to use. In the future, we envision that tools like AlphaEvolve could be used to systematically assess the difficulty of large classes of mathematical bounds or conjectures. This could lead to a new type of classification, allowing researchers to semi-automatically label certain inequalities as " AlphaEvolve -hard", indicating their resistance to AlphaEvolve -based methods. Conversely, other problems could be flagged as being amenable to further attacks by both theoretical and computer-assisted techniques, thereby directing future research efforts more effectively.5. Future work

The mathematical developments in

AlphaEvolve represent a significant step toward automated mathematical discovery, though there are many future directions that are wide open. Given the nature of the human-machine interface, we imagine a further incorporation of a computer-assisted proof into the output of AlphaEvolve in the future, leading to AlphaEvolve first finding the candidate, then providing the e.g. Lean code of such computer-assisted proof to validate it, all in an automatic fashion. In this work, we have demonstrated that in rare cases this is already possible, by providing an example of a full pipeline from discovery to formalization, leading to further insights that when combined with human expertise yield stronger results. This paper represents a first step of a long-term goal that is still in progress, and we expect to explore more in this direction. The line drawn by this paper is solely due to human time and paper length constraints, but not by our computational capabilities. Specifically, in some of the problems we believe that (ongoing and future) further exploration might lead to more and better results.Acknowledgements: JGS has been partially supported by the MICINN (Spain) research grant number PID2021– 125021NA–I00; by NSF under Grants DMS-2245017, DMS-2247537 and DMS-2434314; and by a Simons Fellowship. This material is based upon work supported by a grant from the Institute for Advanced Study School of Mathematics. TT was supported by the James and Carol Collins Chair, the Mathematical Analysis & Application Research Fund, and by NSF grants DMS-2347850, and is particularly grateful to recent donors to the Research Fund.

We are grateful for contributions, conversations and support from Matej Balog, Henry Cohn, Alex Davies, Demis Hassabis, Ray Jiang, Pushmeet Kohli, Freddie Manners, Alexander Novikov, Joaquim Ortega-Cerdà, Abigail See, Eric Wieser, Junyan Xu, Daniel Zheng, and Goran Žužić. We are also grateful to Alex Bäuerle, Adam Connors, Lucas Dixon, Fernanda Viegas, and Martin Wattenberg for their work on creating the user interface for

AlphaEvolve that lets us publish our experiments so others can explore them.6. Mathematical problems where AlphaEvolve was tested

In our experiments we took problems (both solved and unsolved) from the mathematical literature, most of which could be reformulated in terms of obtaining upper and/or lower bounds on some numerical quantity (which could depend on one or more parameters, and in a few cases was multi-dimensional instead of scalar-valued). Many of these quantities could be expressed as a supremum or infimum of some score function over some set (which could be finite, finite dimensional, or infinite dimensional). While both upper and lower bounds are of interest, in many cases only one of the two types of bounds was amenable to an

AlphaEvolve approach, as it is a tool designed to find interesting mathematical constructions, i.e., examples that attempt to optimize the score function, rather than prove bounds that are valid for all possible such examples. In the cases where the domain of the score function was infinite-dimensional (e.g., a function space), an additional restriction or projection to a finite dimensional space (e.g., via discretization or regularization) was used before AlphaEvolve was applied to the problem.In many cases,

AlphaEvolve was able to match (or nearly match) existing bounds (some of which are known or conjectured to be sharp), often with an interpretable description of the extremizers, and in several cases could improve upon the state of the art. In other cases, AlphaEvolve did not even match the literature bounds, but we have endeavored to document both the positive and negative results for our experiments here to give a more accurate portrait of the strengths and weaknesses of AlphaEvolve as a tool. Our goal is to share the results on all problems we tried, even on those we attempted only very briefly, to give an honest account of what works and what does not.In the cases where

AlphaEvolve improved upon the state of the art, it is likely that further work, using either a version of AlphaEvolve with improved prompting and setup, a more customized approach guided by theoretical considerations or traditional numerics, or a hybrid of the two approaches, could lead to further improvements; this has already occurred in some of the AlphaEvolve results that were previously announced in [1]. We hope that the results reported here can stimulate further such progress on these problems by a broad variety of methods.Throughout this section, we will use the following notation: We will say that (resp. ) whenever there exists a constant independent of such that (resp. ).

6.1 Finite field Kakeya and Nikodym sets

Problem 1: Kakeya and Nikodym sets

Let , and let be a prime power. Let be a finite field of order . A Kakeya set is a set that contains a line in every direction, and a Nikodym set is a set with the property that every point in is contained in a line that is contained in . Let denote the least size of a Kakeya or Nikodym set in respectively.

These quantities have been extensively studied in the literature, due to connections with block designs, the polynomial method in combinatorics, and a strong analogy with the Kakeya conjecture in other settings such as Euclidean space. The previous best known bounds for large can be summarized as follows:

- We have the general inequality

which reflects the fact that a projective transformation of a Nikodym set is essentially a Kakeya set; see [25].

- We trivially have .

- is equal to when is odd and when is even [31,32].

- In contrast, from the theory of blocking sets, is known to be at least , where is the fractional part of [33]. When is a perfect square, this bound is sharp up to a lower order error [34]1. However, there is no obvious way to adapt such results to the non-perfect-square case.

In the notation of that paper, Nikodym sets are the "green" portion of a "green--black coloring".

- In general, we have the bounds

see [35]. In particular, and thus also , thanks to Equation 1.

- It is conjectured that ([31], Conjecture 1.2). In the regime when goes to infinity while the characteristic stays bounded (which in particular includes the case of even ) the stronger bound is known ([36], Theorem 1.6). In three dimensions the conjecture would be implied by a further conjecture on unions of lines ([31], Conjecture 1.4).

- The classes of Kakeya and Nikodym sets can both be checked to be closed under Cartesian products, giving rise to the inequalities and for any . When is a perfect square, one can combine this observation with the constructions in [34] (and the trivial bound ) to obtain an upper bound

for any fixed .

We applied

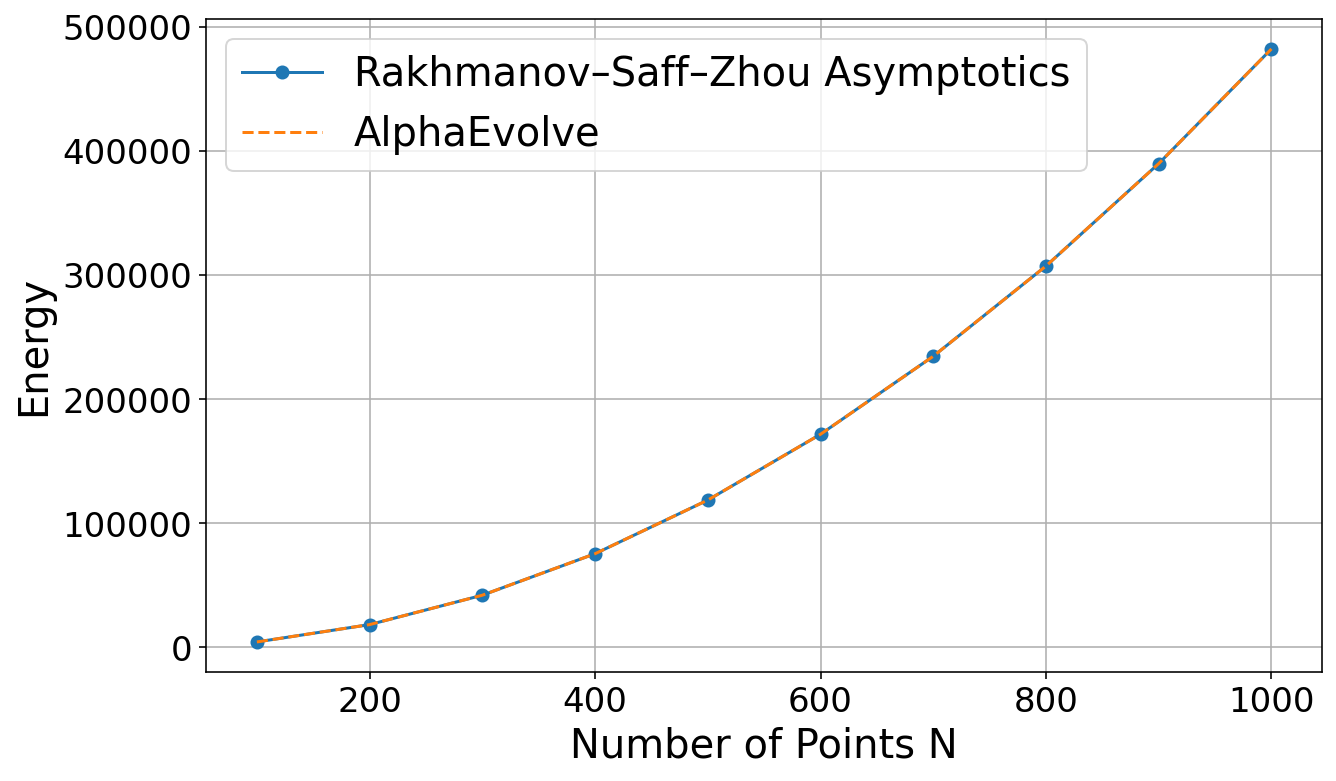

AlphaEvolve to search for new constructions of Kakeya and Nikodym sets in and , for various values of . Since we were after a construction that works for all primes / prime powers (or at least an infinite class of primes / prime powers), we used the generalizer mode of AlphaEvolve. That is, every construction of AlphaEvolve was evaluated on many large values of or , and the final score was the average normalized size of all these constructions. This encouraged AlphaEvolve to find constructions that worked for many values of or simultaneously.Throughout all of these experiments, whenever

AlphaEvolve found a construction that worked well on a large range of primes, we asked Deep Think to give us an explicit formula for the sizes of the sets constructed. If Deep Think succeeded in deriving a closed form expression, we would check if this formula matched our records for several primes, and if it did, it gave us some confidence that the Deep Think produced proof was likely correct. To gain absolute confidence, in one instance we then used AlphaProof to turn this natural language proof into a fully formalized Lean proof. Unfortunately, this last step was possible only when the proof was simple enough; in particular all of its necessary steps needed to have already been implemented in the Lean library mathlib.This investigation into Kakeya sets yielded new constructions with lower-order improvements in dimensions , , and . In three dimensions,

AlphaEvolve discovered multiple new constructions, such as one demonstrating the bound that worked for all primes , via the explicit Kakeya setwhere and is the set of quadratic residues (including ). This slightly refines the previously best known bound from [35]. Since we found so many promising constructions that would have been tedious to verify manually, we found it useful to have

Deep Think produce proofs of formulas for the sizes of the produced sets, which we could then cross-reference with the actual sizes for several primes . When we wanted to be absolutely certain that the proof was correct, here we used AlphaProof to produce a fully formal Lean proof as well. This was only possible because the proofs typically used reasonably elementary, though quite long, number theoretic inclusion-exclusion computations.In four dimensions, the difficulty ramped up quite a bit, and many of the methods that worked for stopped working altogether.

AlphaEvolve came up with a construction demonstrating the bound , again for primes . As in the case, the coefficients in the leading two terms match the best-known construction in [35] (and may have a modest improvement in the term). In the proof of this construction, Deep Think revealed a link to elliptic curves, which explains why the lower-order error terms grow like instead of being simple polynomials. Unfortunately, this also meant that the proofs were too difficult for AlphaProof to handle, and since there was no exact formula for the size of the sets, we could not even cross-reference the asymptotic formula claimed by Deep Think with our actual computed numbers. As such, in stark contrast to the case, we had to resort to manually checking the proofs ourselves.On closer inspection, the construction

AlphaEvolve found for the case of the finite field Kakeya problem was not too far from the constructions in the literature, which also involved various polynomial constraints involving quadratic residues; up to trivial changes of variable, AlphaEvolve matched the construction in [35] exactly outside of a three-dimensional subspace of , and was fairly similar to that construction inside that subspace as well. While it is possible that with more classical numerical experimentation and trial and error one could have found such a construction, it would have been rather time-consuming to do so. Overall, we felt this was a great example of AlphaEvolve finding structures with deep number-theoretic properties, especially since the reference [35] was not explicitly made available to AlphaEvolve.The same pattern held in , where we found a construction establishing of size for primes with a

Deep Think proof that we verified by hand. In both the and cases, our results matched the leading two coefficients from [35], but refined the lower order terms (which was not the focus of [35]).The story with Nikodym sets was a bit different and showed more of a back-and-forth between the AI and us.

AlphaEvolve's first attempt in three dimensions gave a promising construction by building complicated high-degree surfaces that Deep Think had a hard time analyzing. By simplifying the approach by hand to use lower-degree surfaces and more probabilistic ideas, we were able to find a better construction establishing the upper bound for fixed , improving on the best known construction. AlphaEvolve's construction, while not optimal, was a great jumping-off point for human intuition. The details of this proof will appear in a separate paper by the third author [25].Another experiment highlighted how important expert guidance can be. As noted earlier in this section, for fields of square order , there are Nikodym sets in two dimensions giving the bound . At first we asked

AlphaEvolve to solve this problem without any hints, and it only managed to find constructions of size . Next, we ran the same experiment again, but this time telling AlphaEvolve that a construction of size was possible. Curiously, this small bit of extra information had a huge impact on the performance: AlphaEvolve now immediately found constructions of size for a small constant , and eventually it discovered various different constructions of size .We also experimented with giving

AlphaEvolve hints from a relevant paper ([33]) and asked it to reproduce the complicated construction in it via code. We measured its progress just as before, by looking simply at the size of the construction it created on a wide range of primes. After a few hundred iterations AlphaEvolve managed to reproduce the constructions in the paper (and even slightly improve on it via some small heuristics that happen to work well for small primes).6.2 Autocorrelation inequalities

The convolution of two (absolutely integrable) functions is defined by the formula

When is either equal to or a reflection of , we informally refer to such convolutions as autocorrelations. There has been some literature on obtaining sharp constants on various functional inequalities involving autocorrelations; see [37] for a general survey. In this paper,

AlphaEvolve was applied to some of them via its standard search mode, evolving a heuristic search function that produces a good function within a fixed time budget, given the best construction so far as input. We now set out some notation for some of these inequalities.Problem 2

Let denote the largest constant for which one has

for all non-negative . What is ?

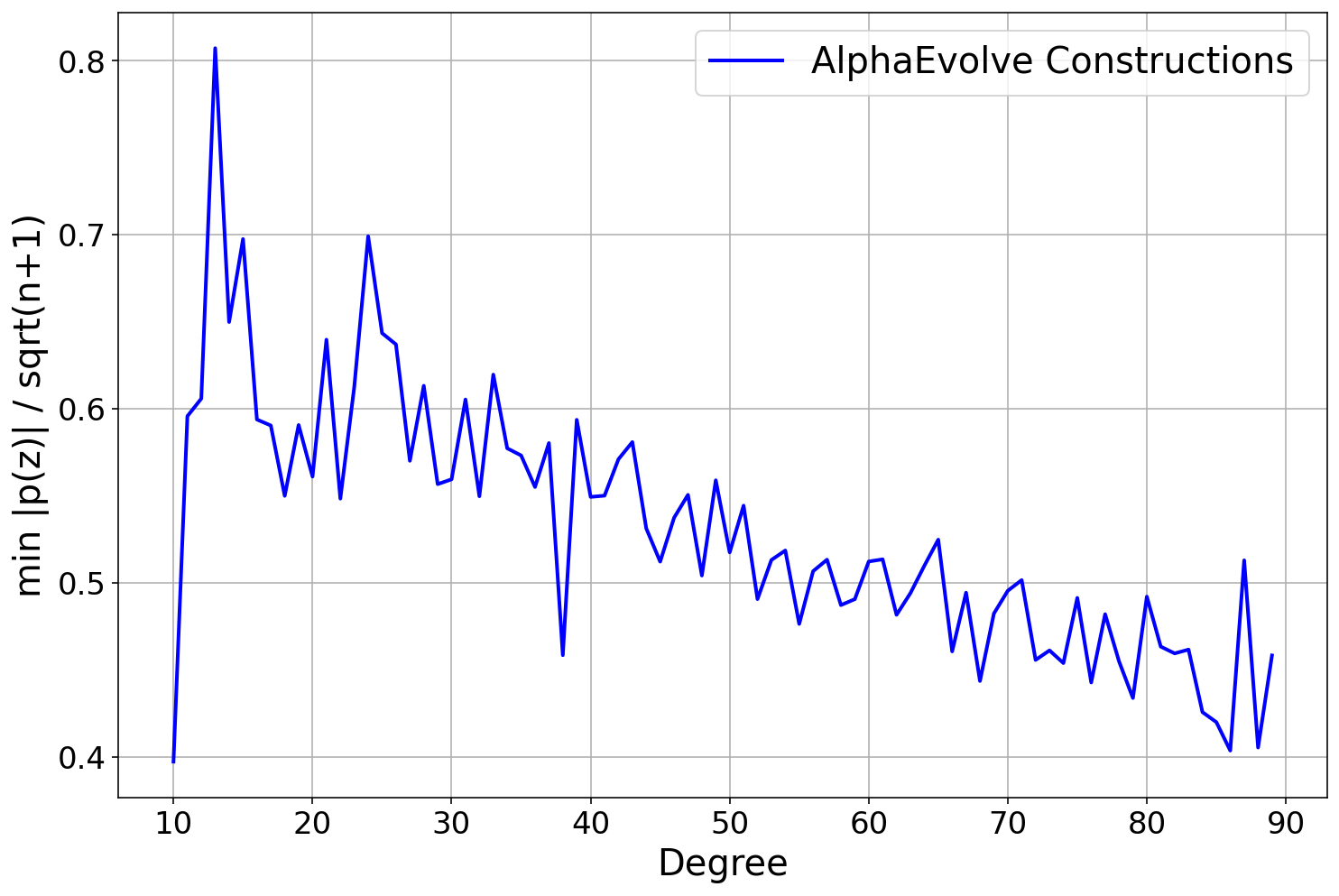

Problem 2 arises in additive combinatorics, relating to the size of Sidon sets. Prior to this work, the best known upper and lower bounds were

with the lower bound achieved in [38] and the upper bound achieved in [39]; we refer the reader to these references for prior bounds on the problem.

Upper and lower bounds for can both be achieved by computational methods, and so both types of bounds are potential use cases for

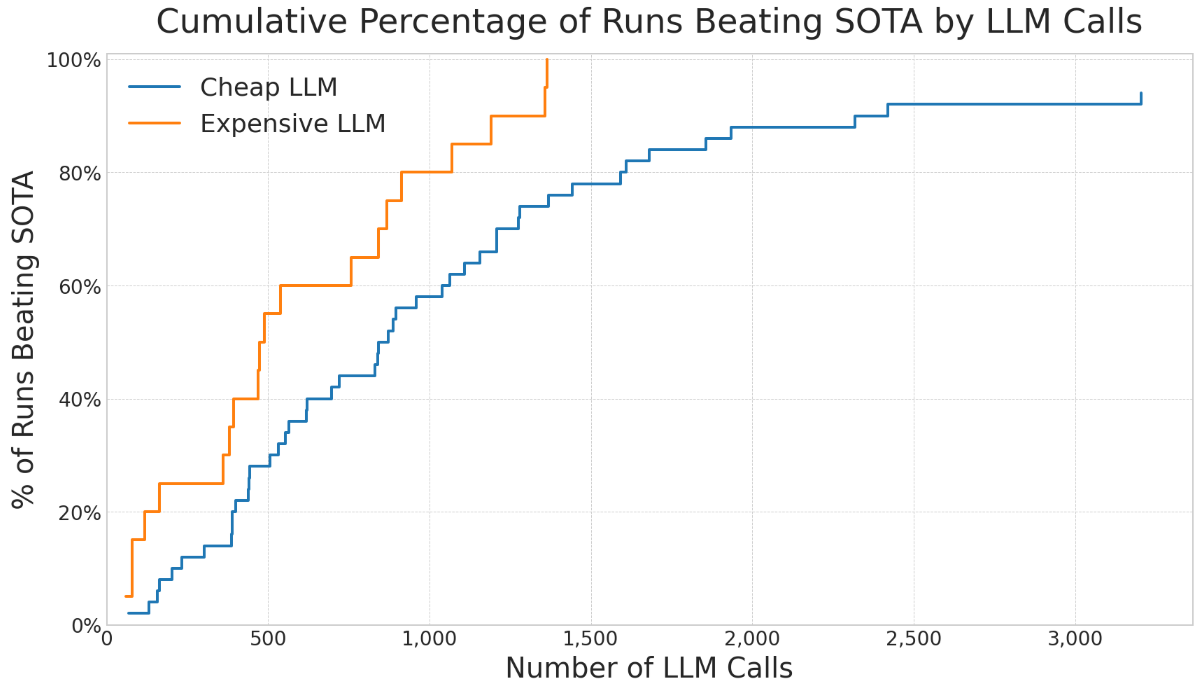

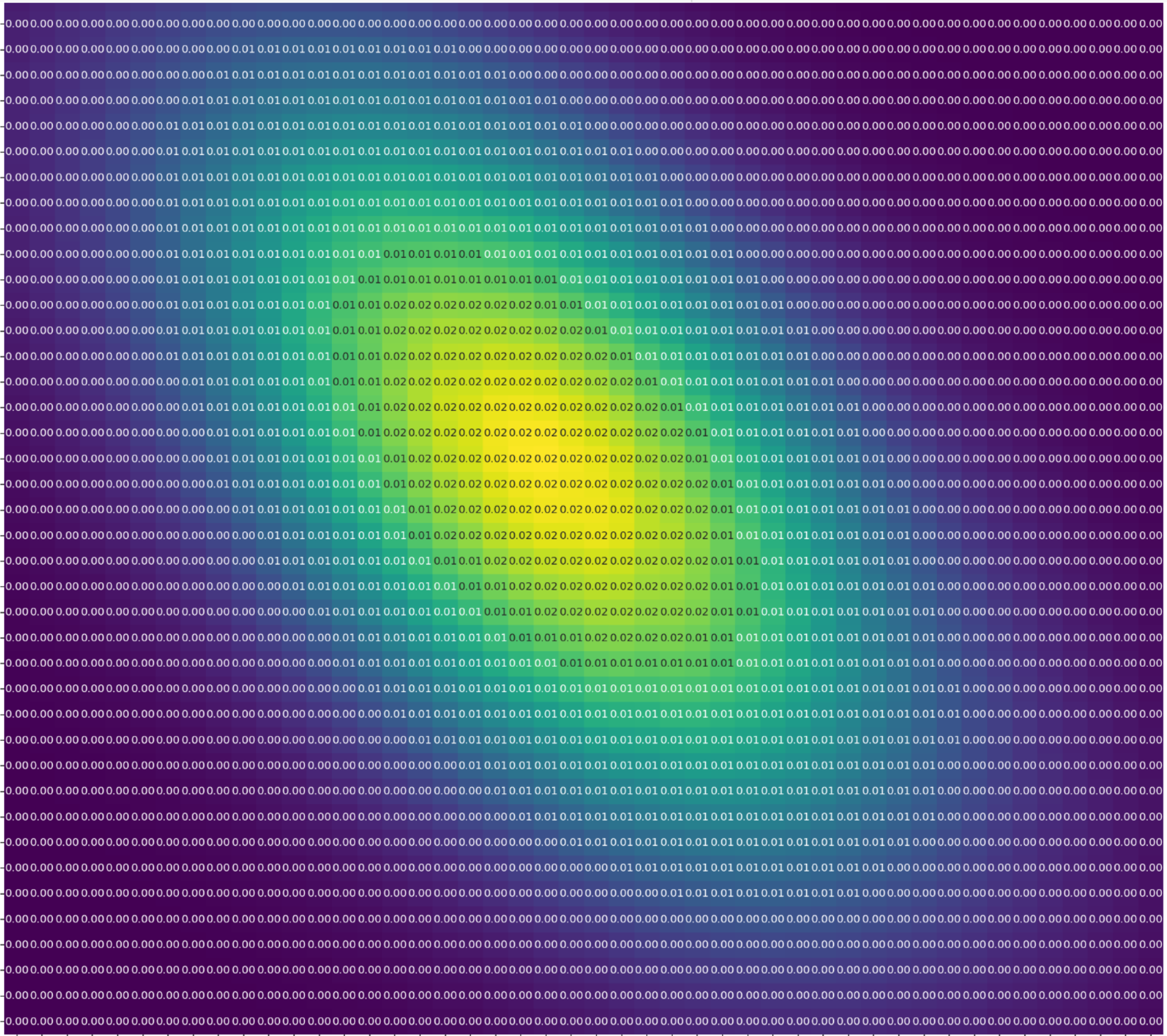

AlphaEvolve. For lower bounds, we refer to [38]. For upper bounds, one needs to produce specific counterexamples . The explicit choicealready gives the upper bound , which at one point was conjectured to be optimal. The improvement comes from a numerical search involving functions that are piecewise constant on a fixed partition of into some finite number of intervals ( is already enough to improve the bound), and optimizing. There are some tricks to speed up the optimization, in particular there is a Newton type method in which one selects an intelligent direction in which to perturb a candidate , and then moves optimally in that direction. See [39] for details. After we told

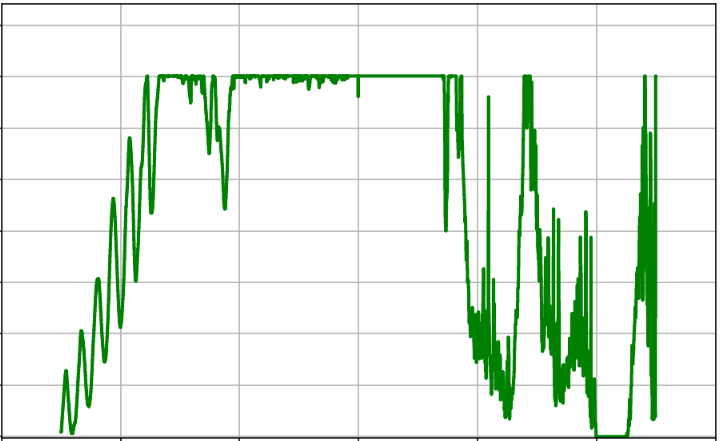

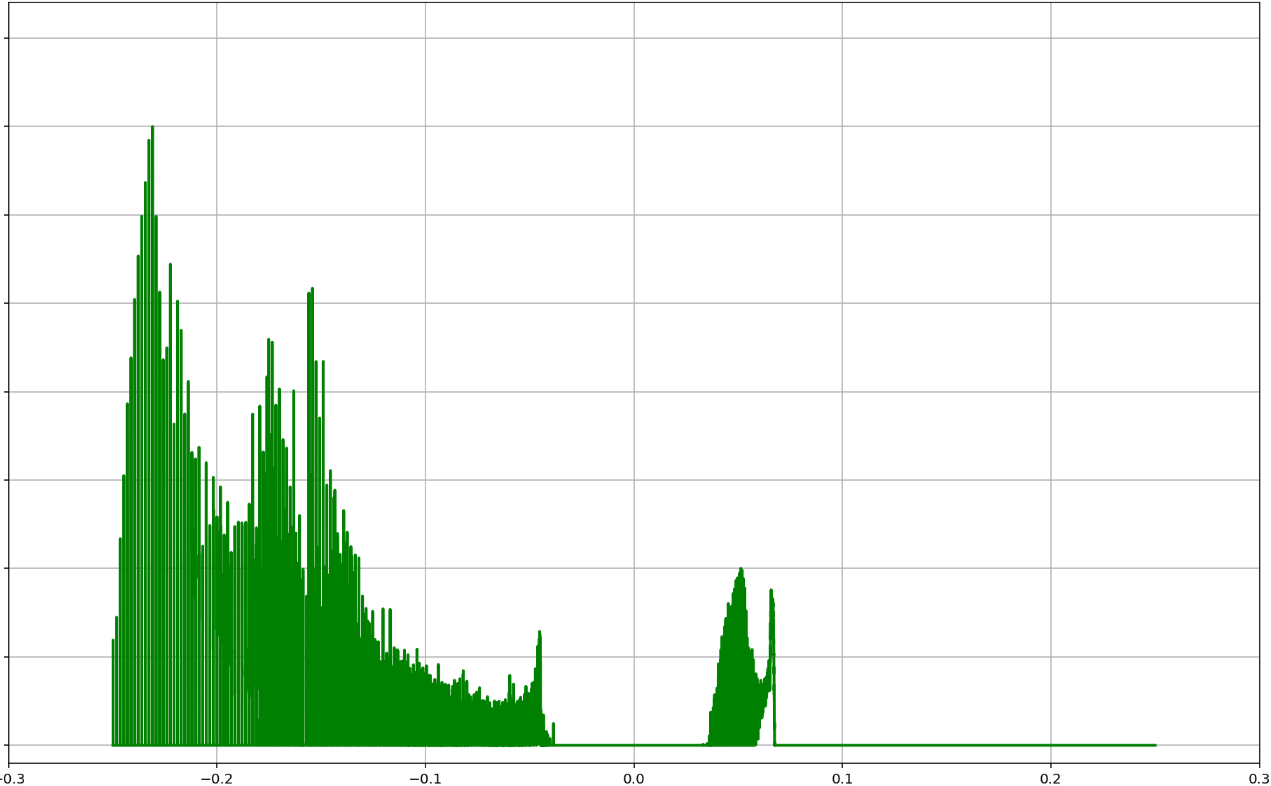

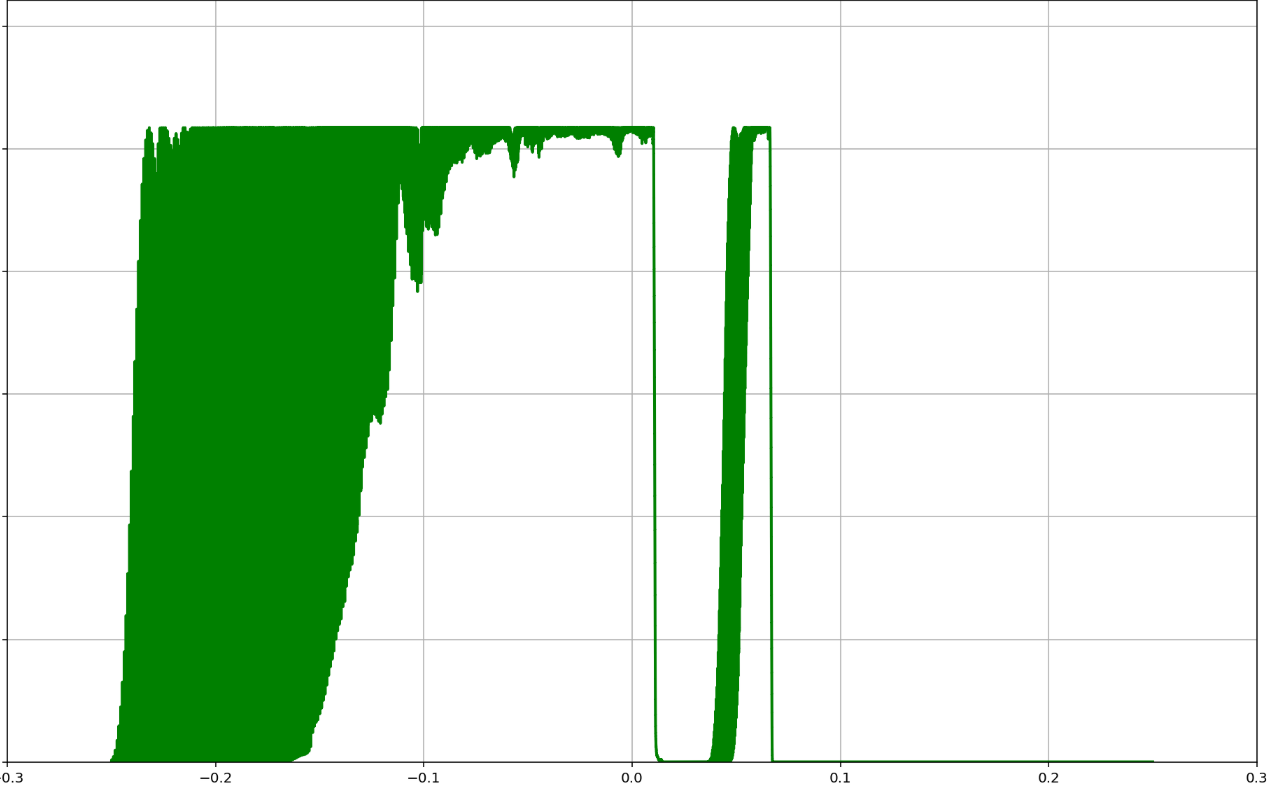

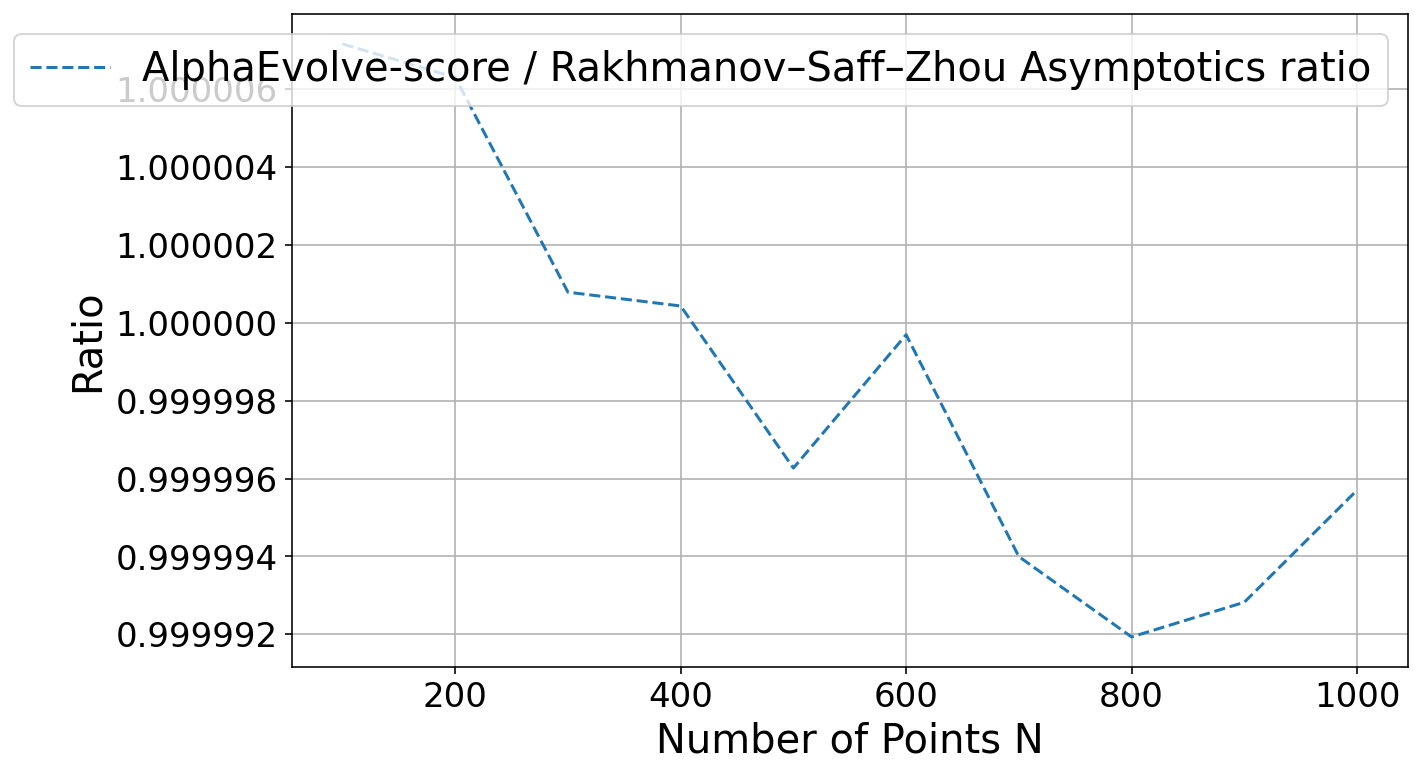

AlphaEvolve about this Newton type method, it found heuristic search methods using "cubic backtracking" that produced constructions reducing the upper bound to . See Repository of Problems for several constructions and some of the search functions that got evolved.After our results, Damek Davis performed a very thorough meta-analysis [40] using different optimization methods and was not able to improve on the results, perhaps due to the highly irregular nature of the numerical optimizers (see Figure 4). This is an example of how much

AlphaEvolve can reduce the effort required to optimize a problem.The following problem, studied in particular in [39], concerns the extent to which an autocorrelation of a non-negative function can resemble an indicator function.

Problem 3

Let be the best constant for which one has

for non-negative . What is ?

It is known that

with the upper bound being immediate from Hölder's inequality, and the lower bound coming from a piecewise constant counterexample. It is tentatively conjectured in [39] that .

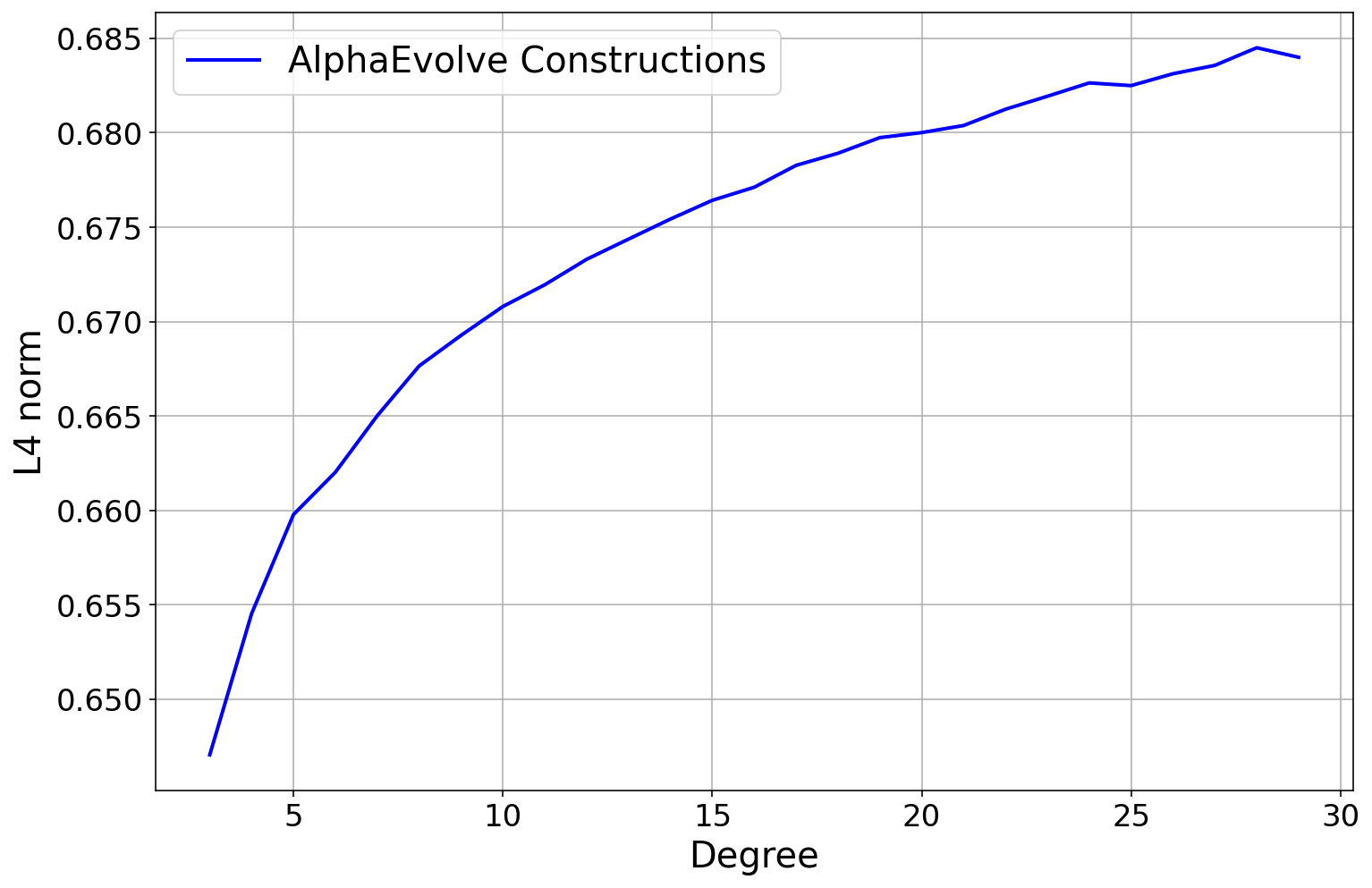

The lower bound requires exhibiting a specific function , and is thus a use case for

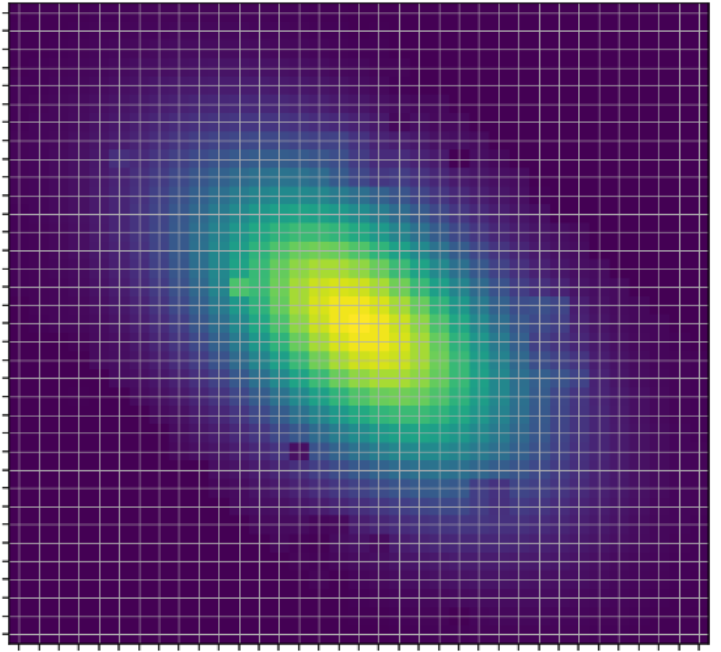

AlphaEvolve. Similarly to how we approached Problem 2, we can restrict ourselves to piecewise constant functions, with a fixed number of equal sized parts. With this simple setup, AlphaEvolve improved the lower bound to in a quick experiment. A recent work of Boyer and Li [41] independently used gradient-based methods to obtain the further improvement . Seeing this result, we ran our experiment for a bit longer. After a few hours AlphaEvolve also discovered that gradient-based methods work well for this problem. Letting it run for several hours longer, it found some extra heuristics that seemed to work well together with the gradient-based methods, and it eventually improved the lower bound to using a step function consisting of 50, 000 parts. We believe that with even more parts, this lower bound can be further improved.Figure 5 shows the discovered step function consisting of 50, 000 parts and its autoconvolution. We believe that the irregular nature of the extremizers is one of the reasons why this optimization problem is difficult to accomplish by traditional means.

One can remove the non-negativity hypothesis in Problem 2, giving a new problem:

Problem 4

Let be the best constant for which one has

for all (note can now take negative values). What is ?

Trivially one has . However, there is a better example that gives a new upper bound on , namely [39]. With the same setup as the previous autocorrelation problems, in a quick experiment

AlphaEvolve improved this to .Problem 5

Let be the largest constant for which

for all non-negative with on and , where we extend by zero outside of . What is ?

The constant controls the asymptotics of the "minimum overlap problem" of Erdős [42], ([43], Problem 36). The bounds

are known; the lower bound was obtained in [44] via convex programming methods, and the upper bound obtained in [45] by a step function construction.

AlphaEvolve managed to improve the upper bound ever so slightly to .The following problem is motivated by a problem in additive combinatorics regarding difference bases.

Problem 6

Let be the smallest constant such that

for . What is ?

In [46] it was shown that

To prove the upper bound, one can assume that is non-negative, and one studies the Fourier coefficients of the autocorrelation . On the one hand, the autocorrelation structure guarantees that these Fourier coefficients are nonnegative. On the other hand, if the minimum in Equation 3 is large, then one can use the Hardy--Littlewood rearrangement inequality to lower bound in terms of the norm of , which is . Optimizing in gives the result.

The lower bound was obtained by using an arcsine distribution (with some epsilon modifications to avoid some technical boundary issues). The authors in [46] reported that attacking this problem numerically "appears to be difficult".

This problem was the very first one we attempted to tackle in this entire project, when we were still unfamiliar with the best practices of using

AlphaEvolve. Since we had not come up with the idea of the search mode for AlphaEvolve yet, instead we simply asked AlphaEvolve to suggest a mathematical function directly. Since this way every LLM call only corresponded to one single construction and we were heavily bottlenecked by LLM calls, we tried to artificially make the evaluation more expensive: instead of just computing the score for the function AlphaEvolve suggested, we also computed the scores of thousands of other functions we obtained from the original function via simple transformations. This was the precursor of our search mode idea that we developed after attempting this problem.The results highlighted our inexperience. Since we forced our own heuristic search method (trying the predefined set of simple transformations) onto

AlphaEvolve, it was much more restricted and did not do well. Moreover, since we let AlphaEvolve suggest arbitrary functions instead of just bounded step functions with fixed step sizes, it always eventually figured out a way to cheat by suggesting a highly irregular function that exploited the numerical integration methods in our scoring function in just the right way, and got impossibly high scores.If we were to try this problem again, we would try the search mode in the space of bounded step functions with fixed step sizes, since this setup managed to improve all the previous bounds in this section.

6.3 Difference bases

This problem was suggested by a custom literature search pipeline based on Gemini 2.5 [47]. We thank Daniel Zheng for providing us with support for it. We plan to explore further literature suggestions provided by AI tools (including open problems) in the future.

Problem 7: Difference bases

For any natural number , let be the size of the smallest set of integers such that every natural number from to is expressible as a difference of two elements of (such sets are known as difference bases for the interval ). Write , and . Establish upper and lower bounds on that are as strong as possible.

It was shown in [48] that converges to as , which is also the infimum of this sequence. The previous best bounds (see [49]) on this quantity were

see [50], [51] . While the lower bound requires some non-trivial mathematical argument, the upper bound proceeds simply by exhibiting a difference set for of cardinality , thus demonstrating that .

We tasked

AlphaEvolve to come up with an integer and a difference set for it, that would yield an improved upper bound. AlphaEvolve by itself, with no expert advice, was not able to beat the 2.6571 upper bound. In order to get a better result we had to show it the correct code for generating Singer difference sets [52]. Using this code AlphaEvolve managed to find a substantial improvement in the upper bound from 2.6571 to 2.6390. The construction can be found in the Repository of Problems.6.4 Kissing numbers

Problem 8: Kissing numbers

For a dimension , define the kissing number to be the maximum number of non-overlapping unit spheres that can be arranged to simultaneously touch a central unit sphere in -dimensional space. Establish upper and lower bounds on that are as strong as possible.

This problem has been studied as early as 1694 when Isaac Newton and David Gregory discussed what would be. The cases and are trivial. The four-dimensional problem was solved by Musin [53], who proved that , using a clever modification of Delsarte's linear programming method [54]. In dimensions 8 and 24, the problem is also solved and the extrema are the lattice and the Leech lattice respectively, giving kissing numbers of and respectively [55,56]. In recent years, Ganzhinov [57], de Laat--Leijenhorst [58] and Cohn--Li [59] managed to improve upper and lower bounds for in dimensions , , and respectively.

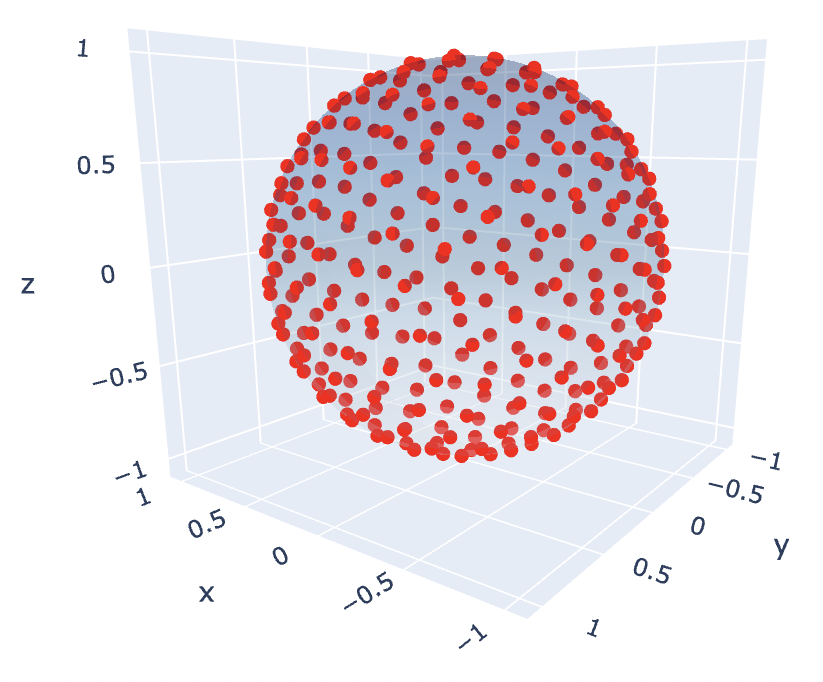

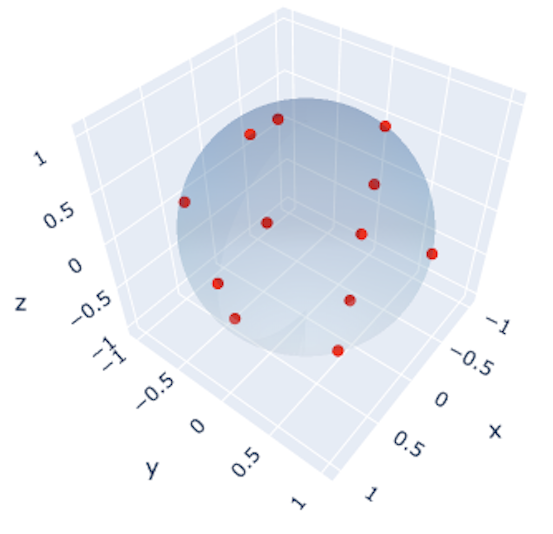

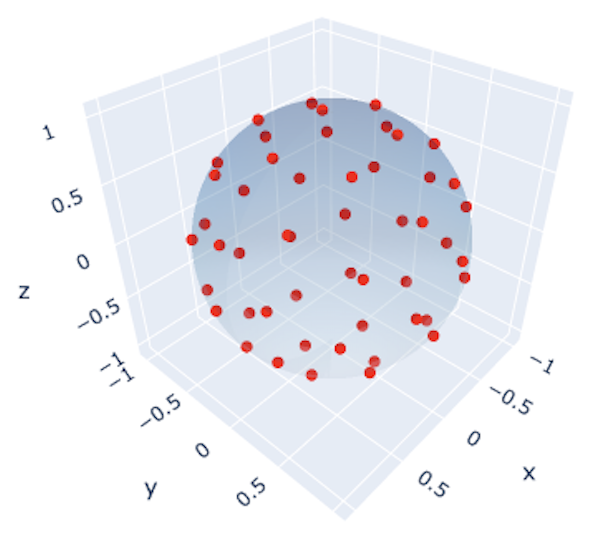

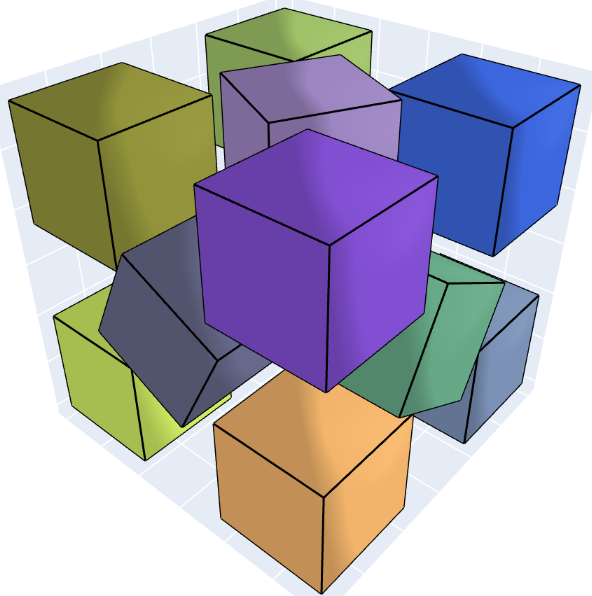

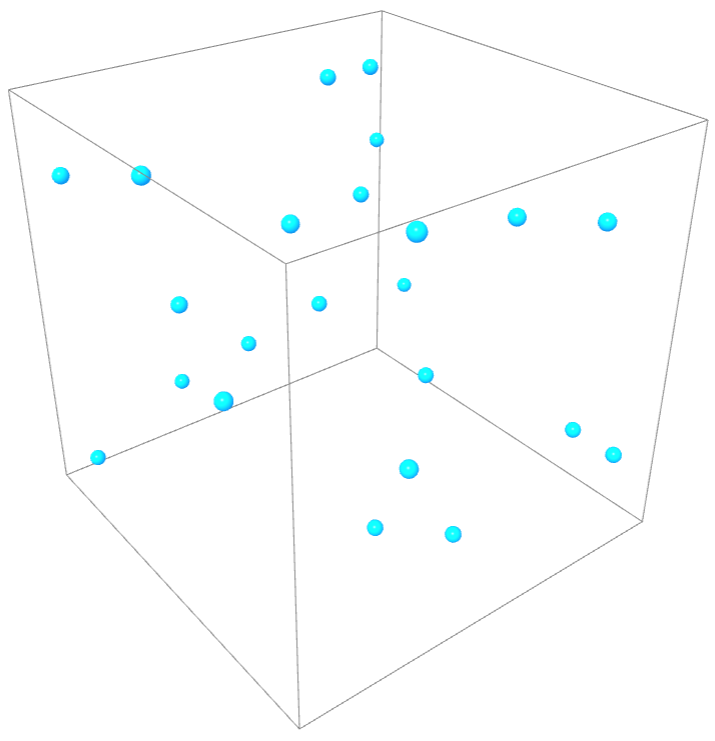

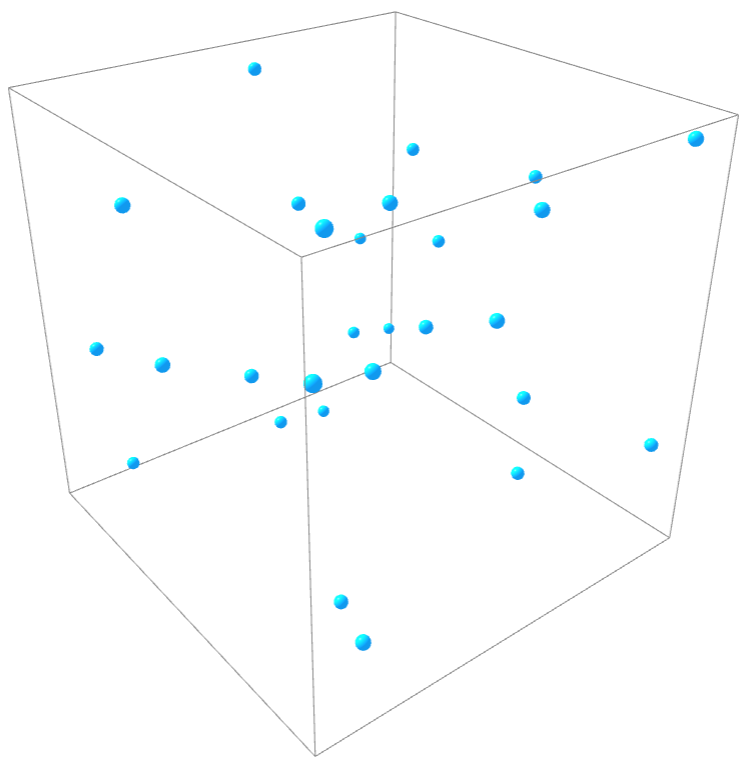

AlphaEvolve was able to improve on the lower bound for , raising it from 592 to 593. See Table 2 for the current best known upper and lower bounds for :Lower bounds on can be generated by producing a finite configuration of spheres, and thus form a potential use case for

AlphaEvolve. We tasked AlphaEvolve to generate a fixed number of vectors, and we placed unit spheres in those directions at distance 2 from the origin. For a pair of spheres, if the distance of their centers was less than 2, we defined their penalty to be , and the loss function of a particular configuration of spheres was simply the sum of all these pairwise penalties. A loss of zero would mean a correct kissing configuration in theory, and this is possible to achieve numerically if e.g. there is a solution where each sphere has some slack. In practice, since we are working with floating point numbers, often the best we can hope for is a loss that is small enough (below was enough) so that we can use simple mathematical results to prove that this approximate solution can then be turned into an exact solution to the problem (for details, see [1,61]).6.5 Kakeya needle problem

Problem 9: Kakeya needle problem

Let . Let denote the minimal area of a union of triangles with vertices , , for some real numbers , and similarly define denote the minimal area of a union of parallelograms with vertices for some real numbers . Finally, define to be the maximal "score"

over triangles as above, and define similarly.

Establish upper and lower bounds for , , , that are as strong as possible.

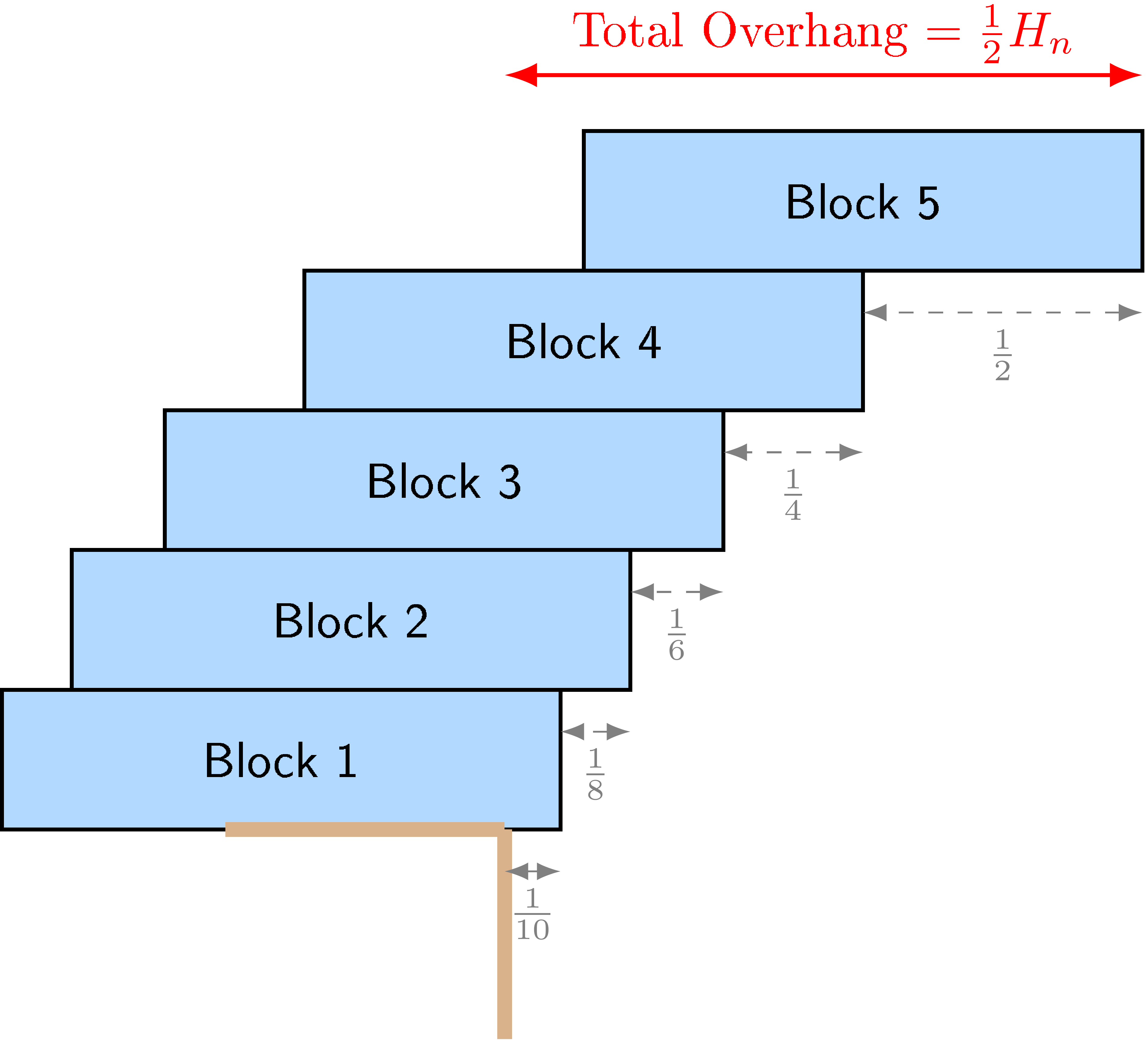

The observation of Besicovitch [62] that solved the Kakeya needle problem (can a unit needle be rotated in the plane using arbitrarily small area?) implied that and both converged to zero as . It is known that

with the lower bound due to Córdoba [63], and the upper bound due to Keich [64]. Since and , we have

and similarly

and so the lower bound of Córdoba in fact follows from the trivial Cauchy--Schwarz bound

and the construction of Keich shows that

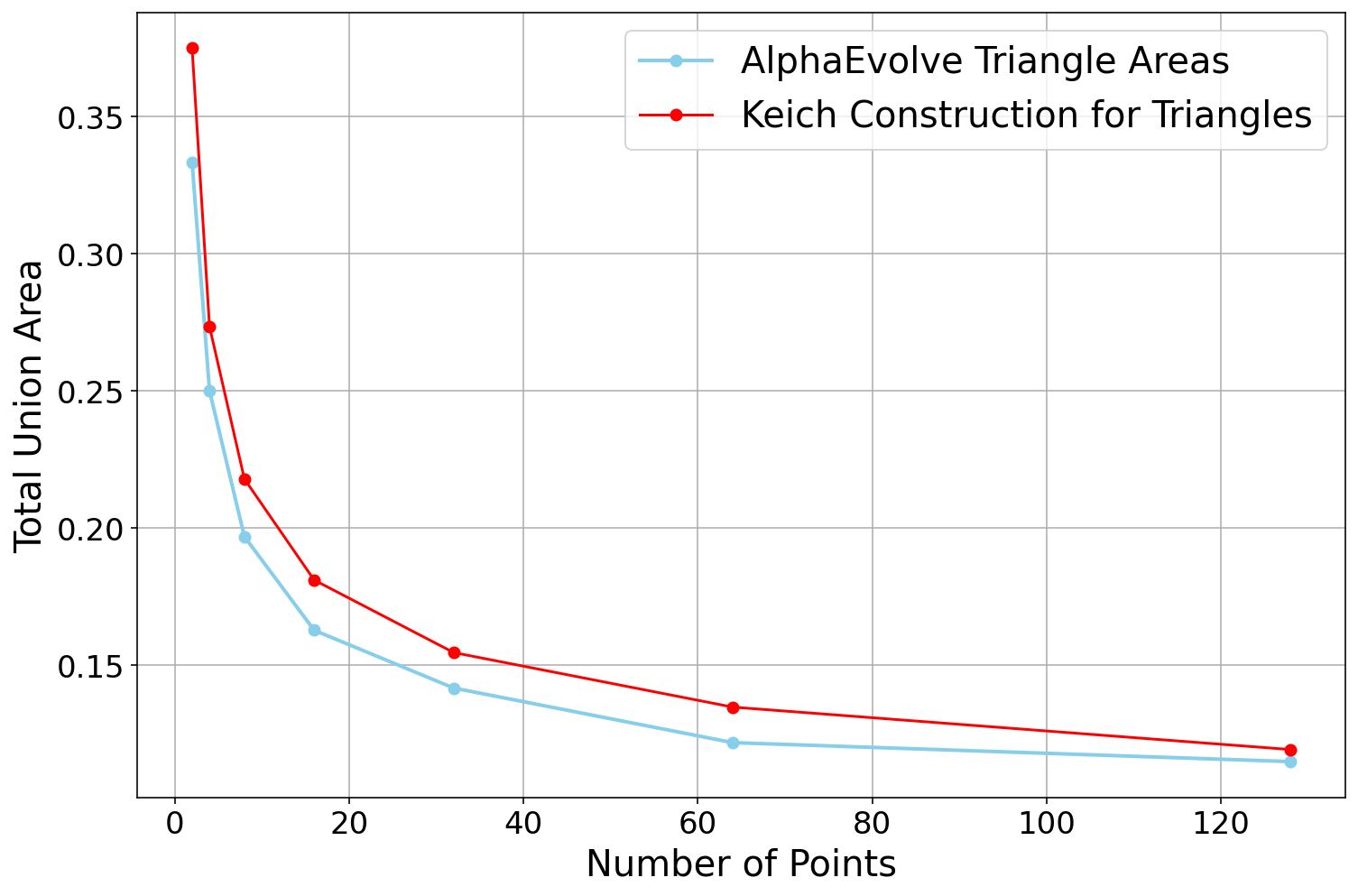

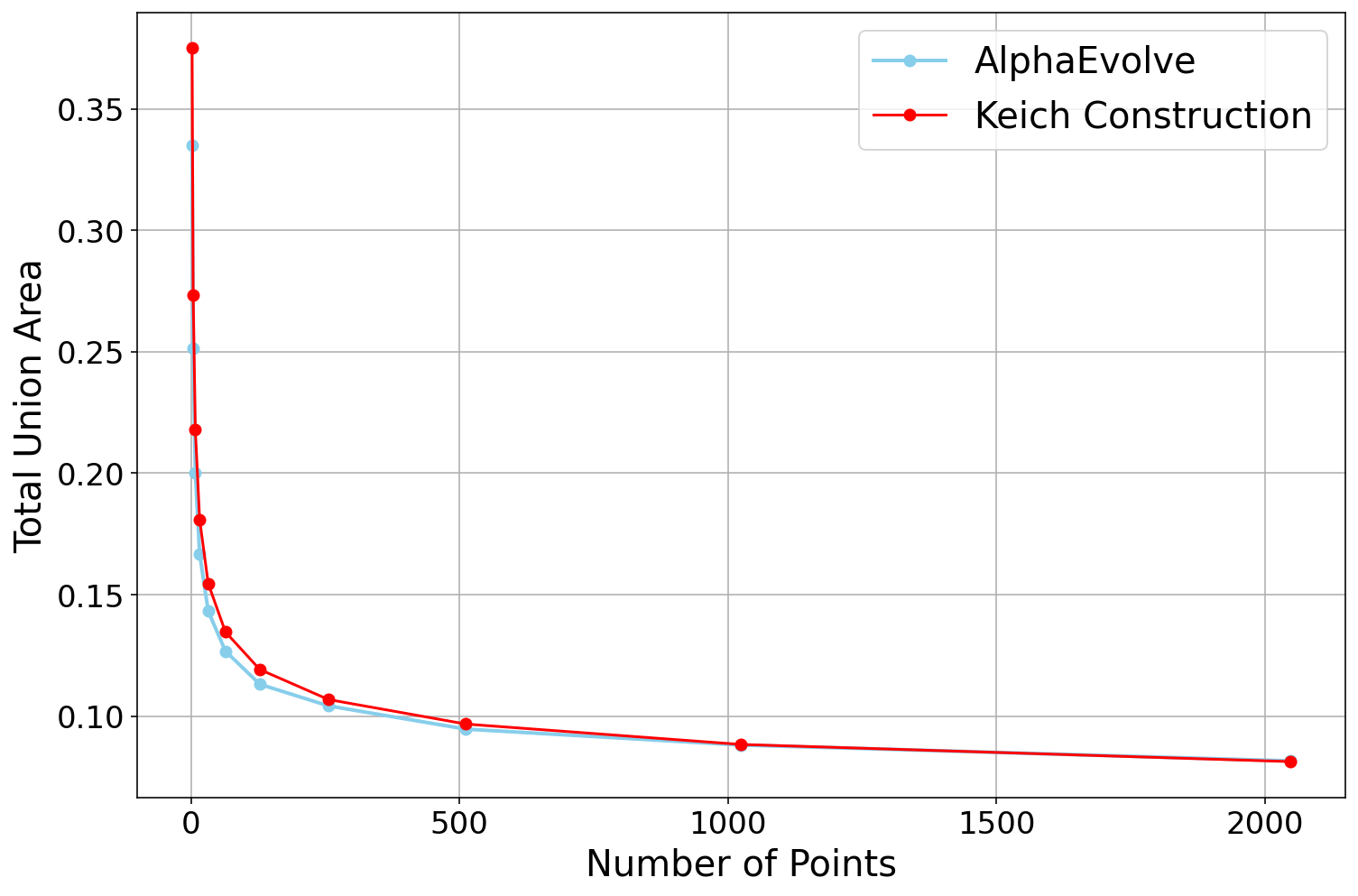

We explored the extent to which

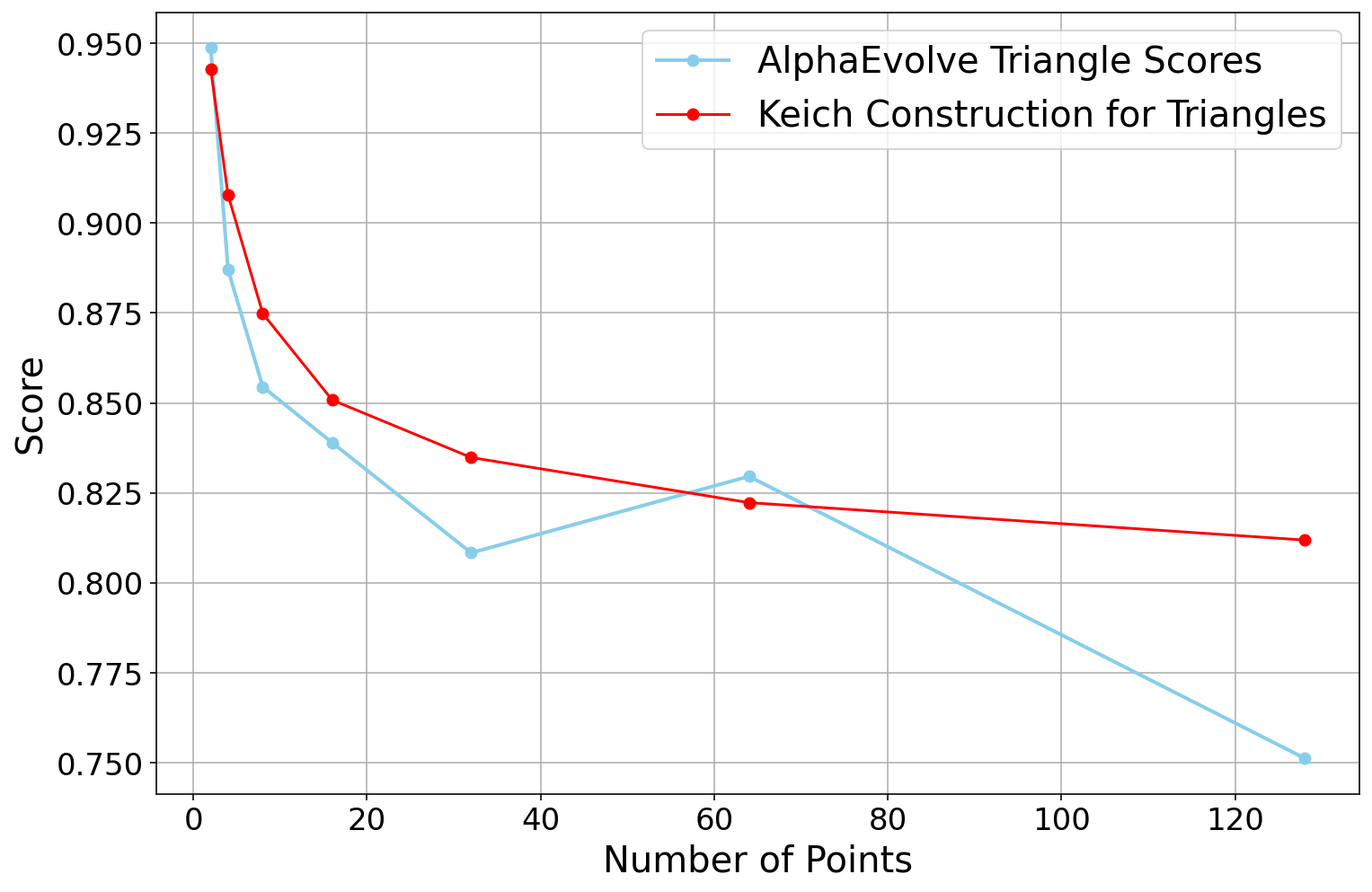

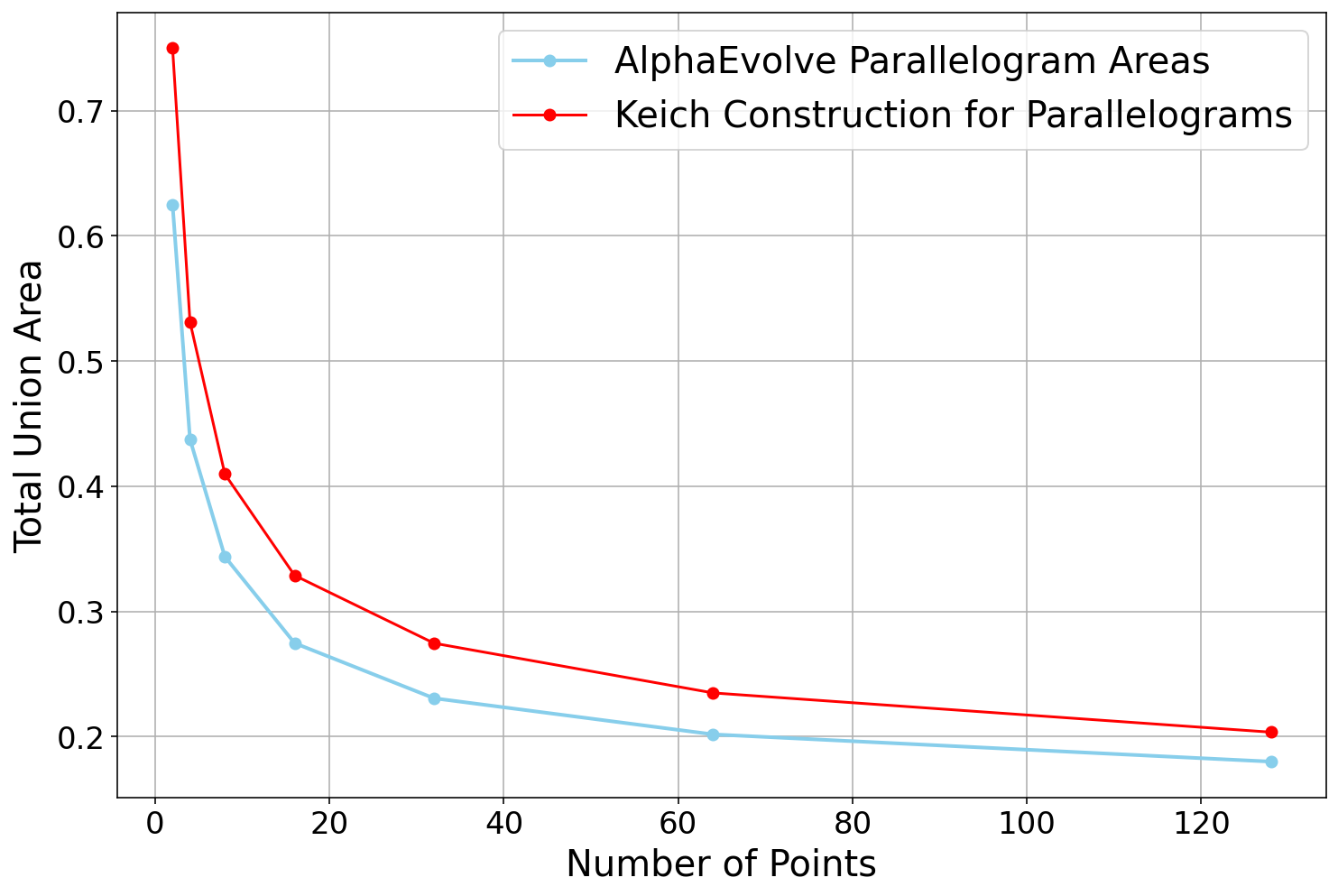

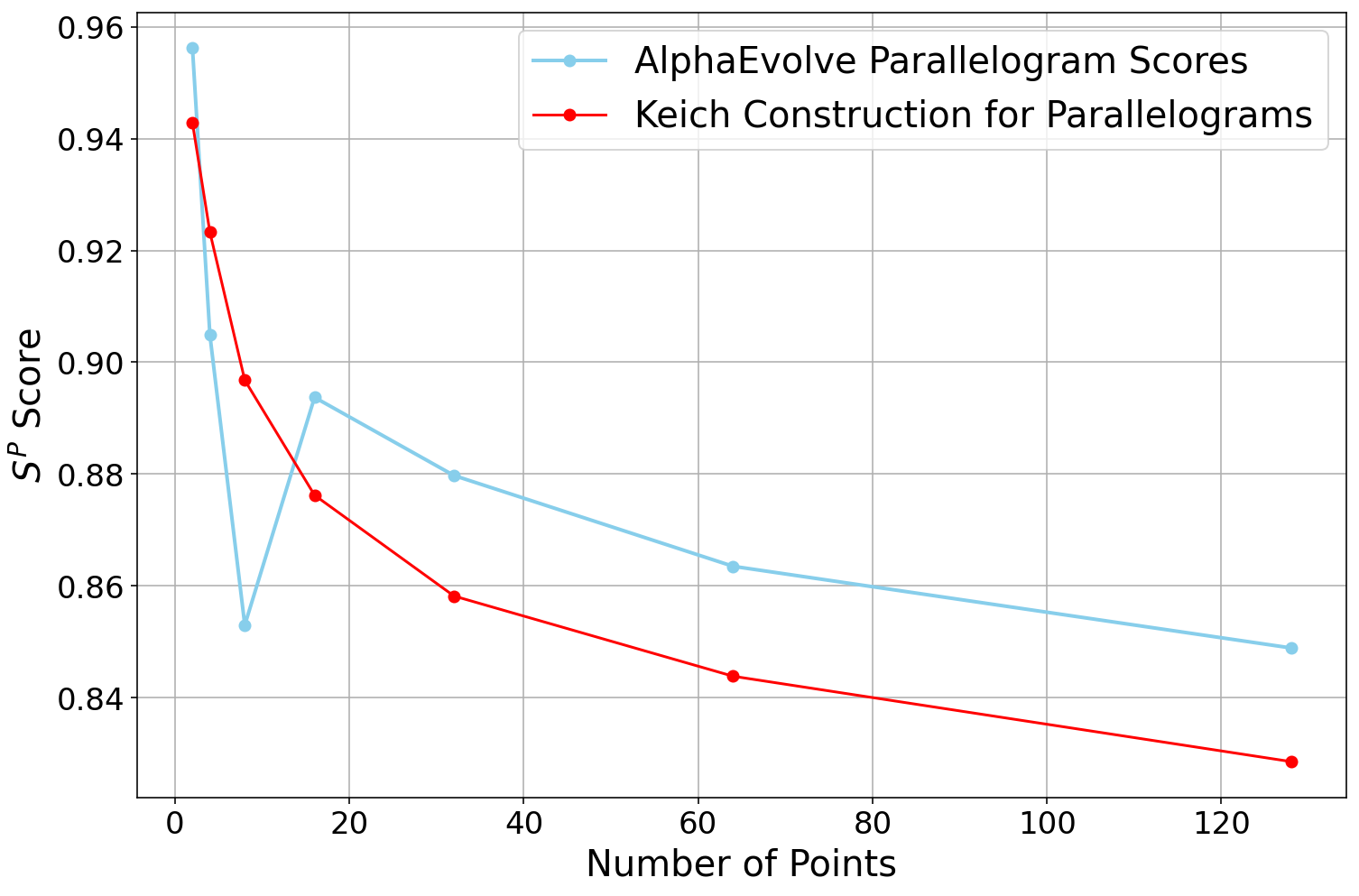

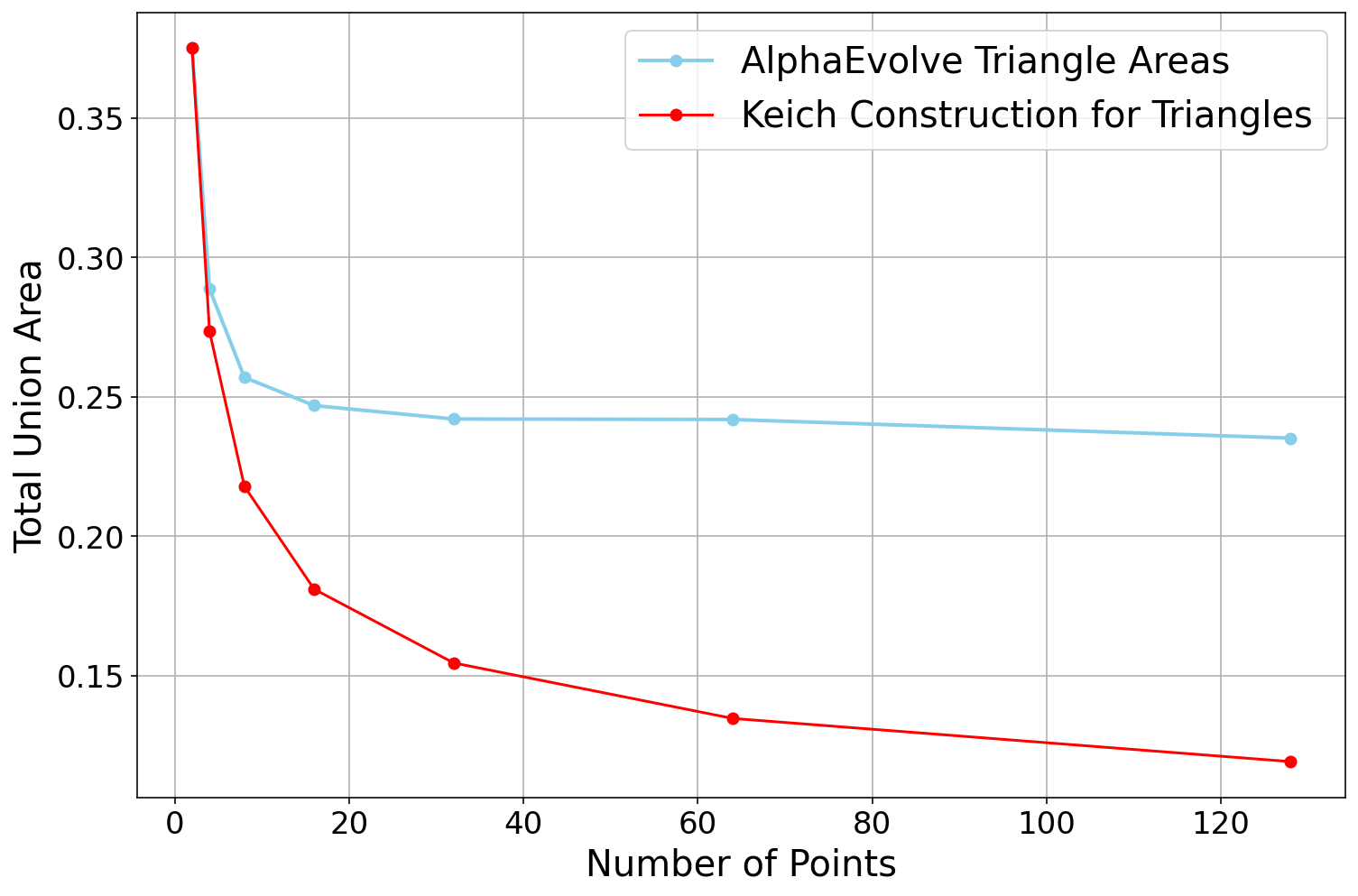

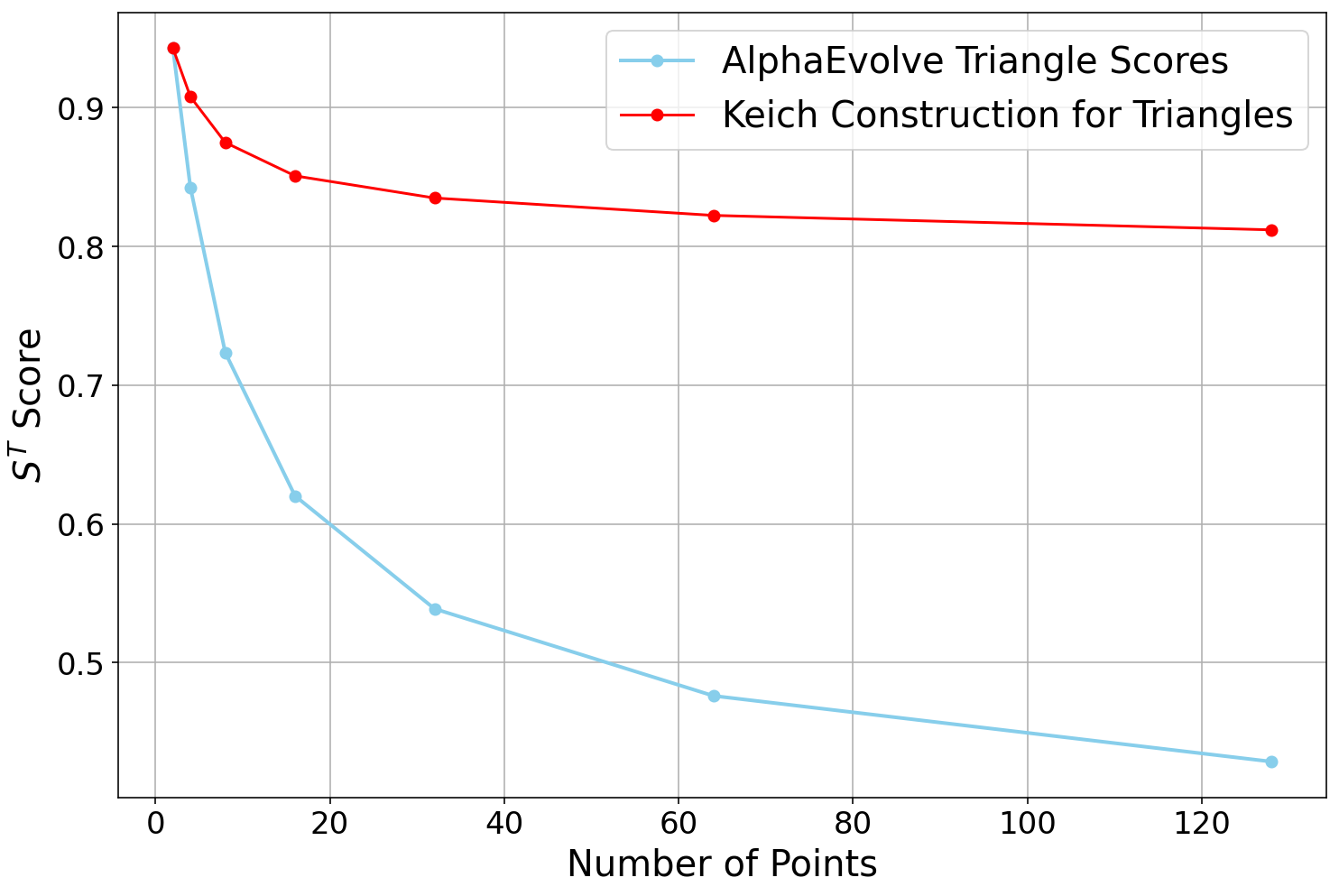

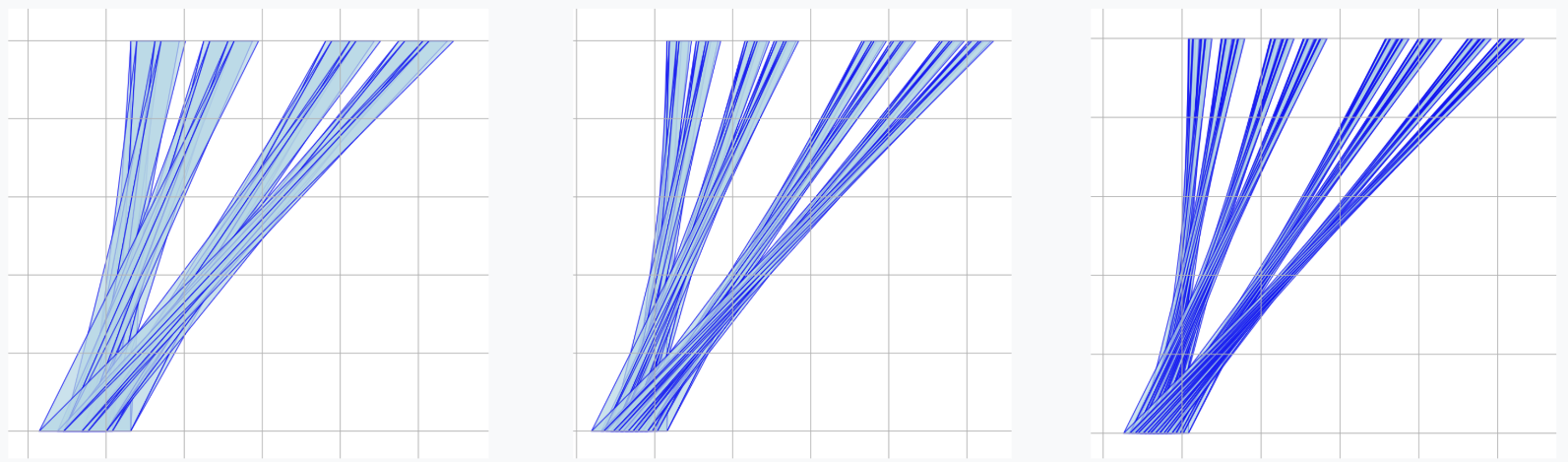

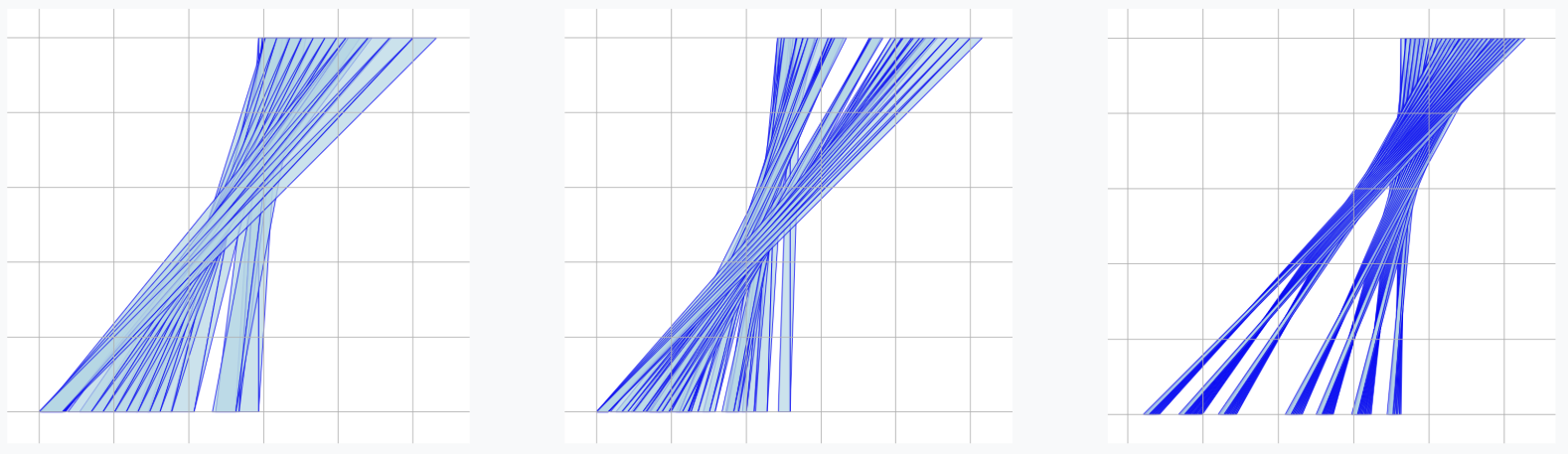

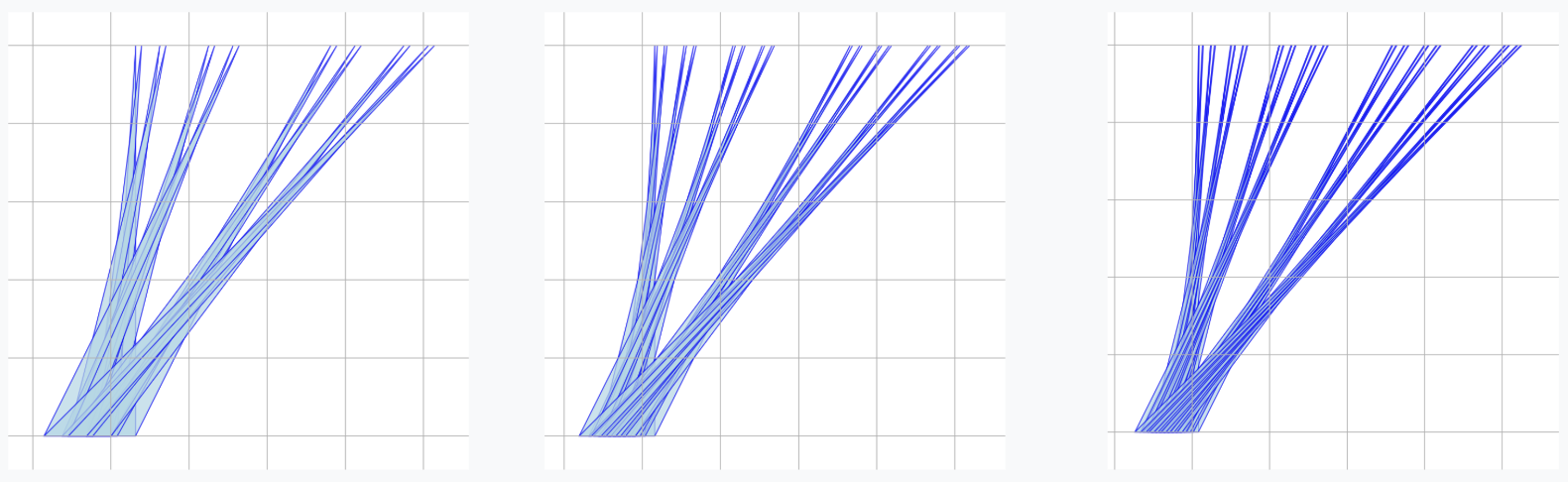

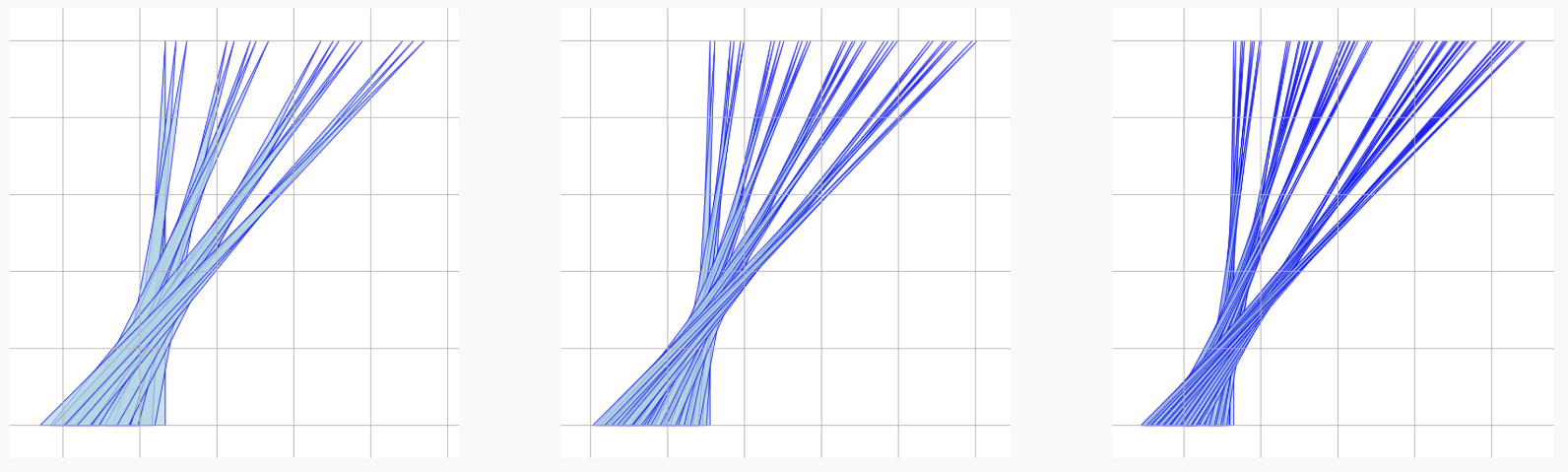

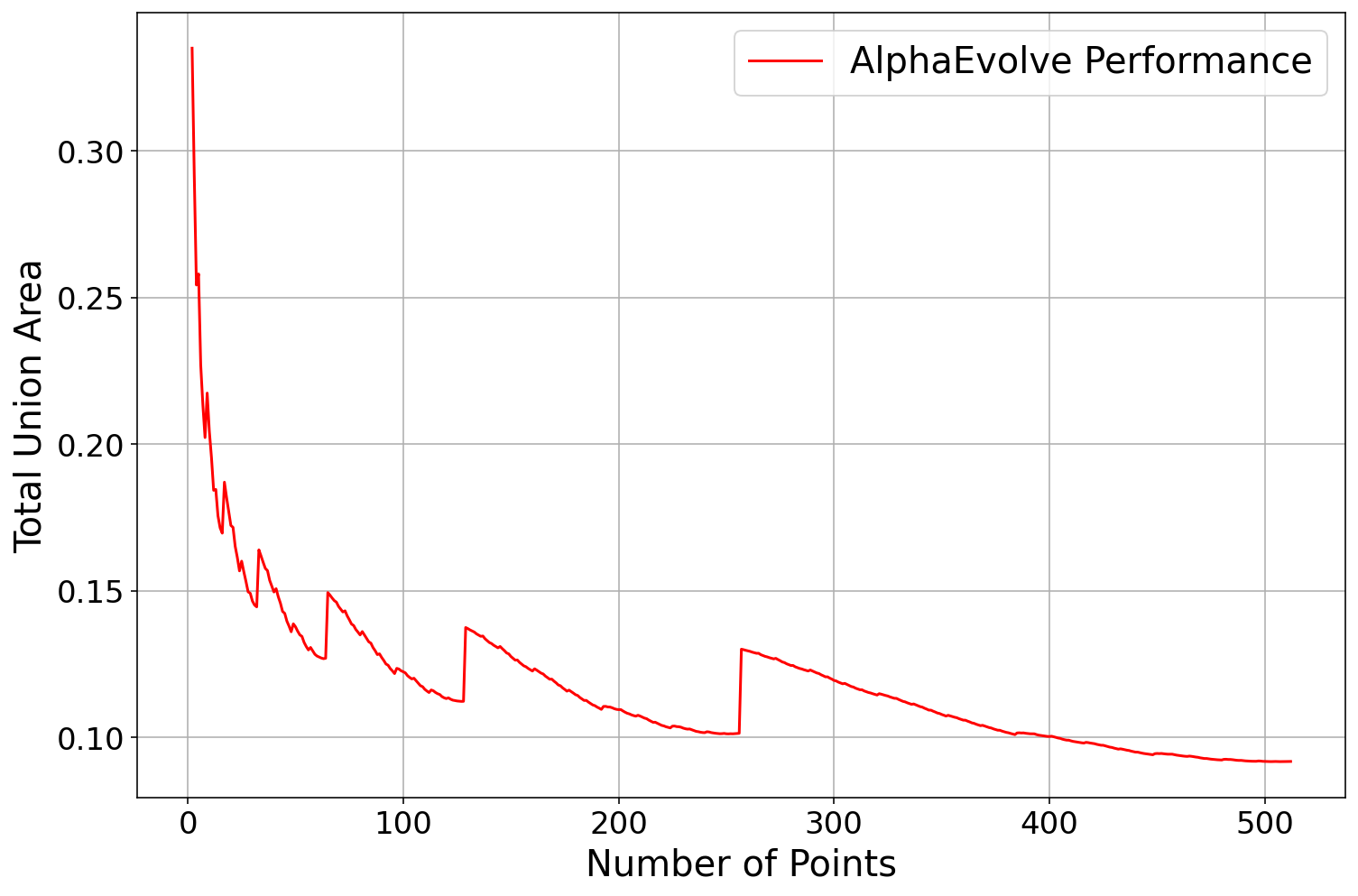

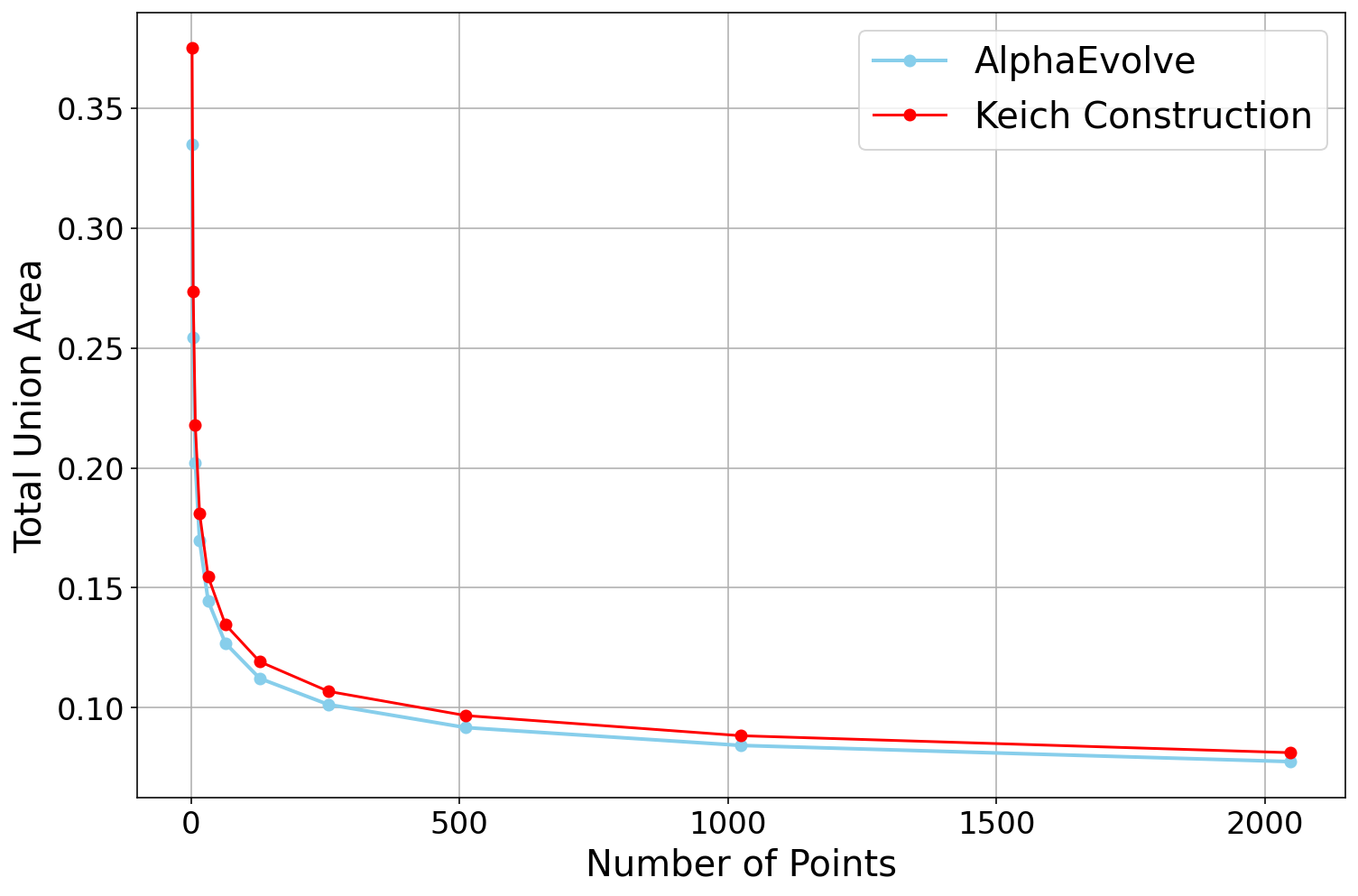

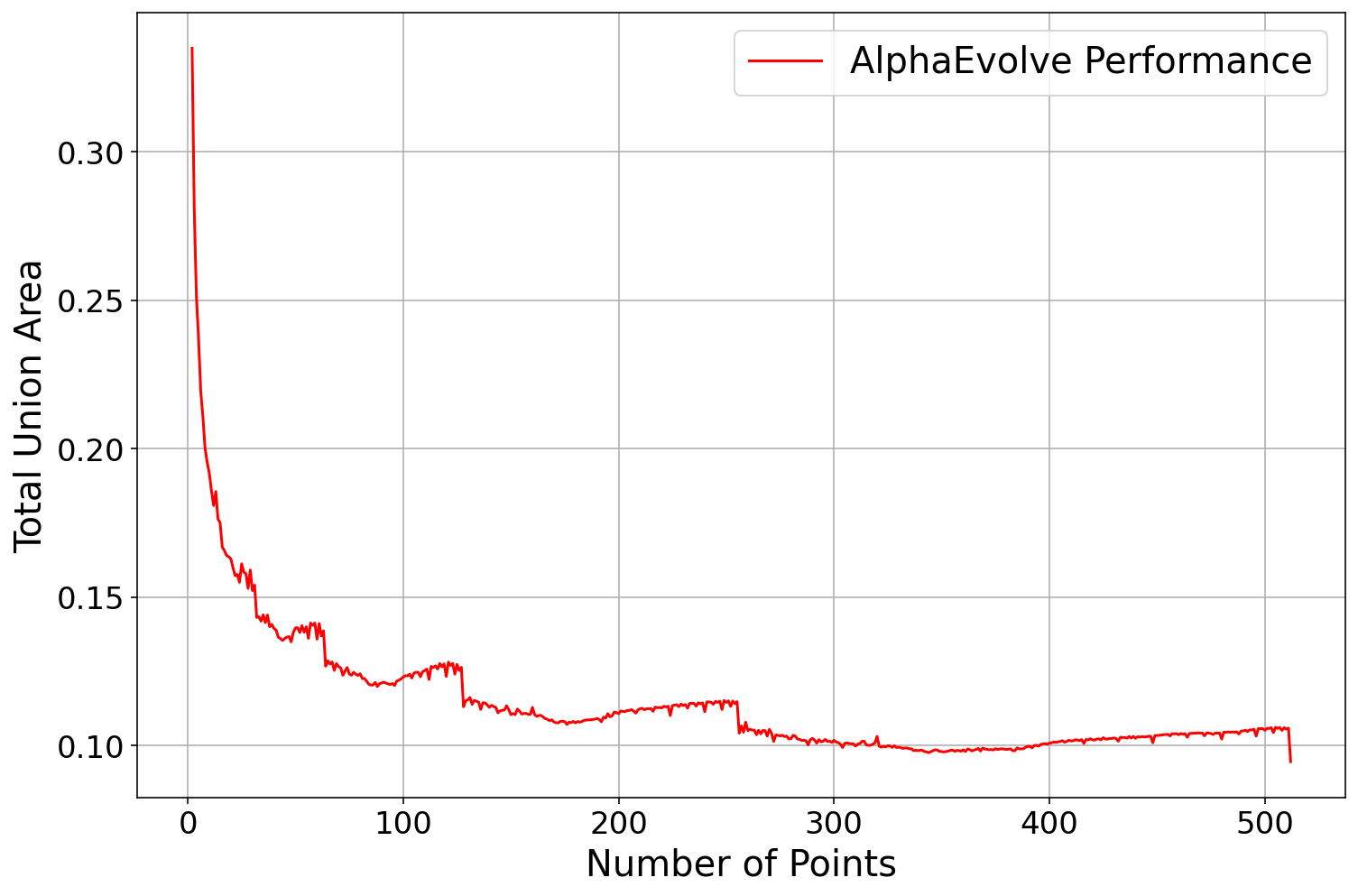

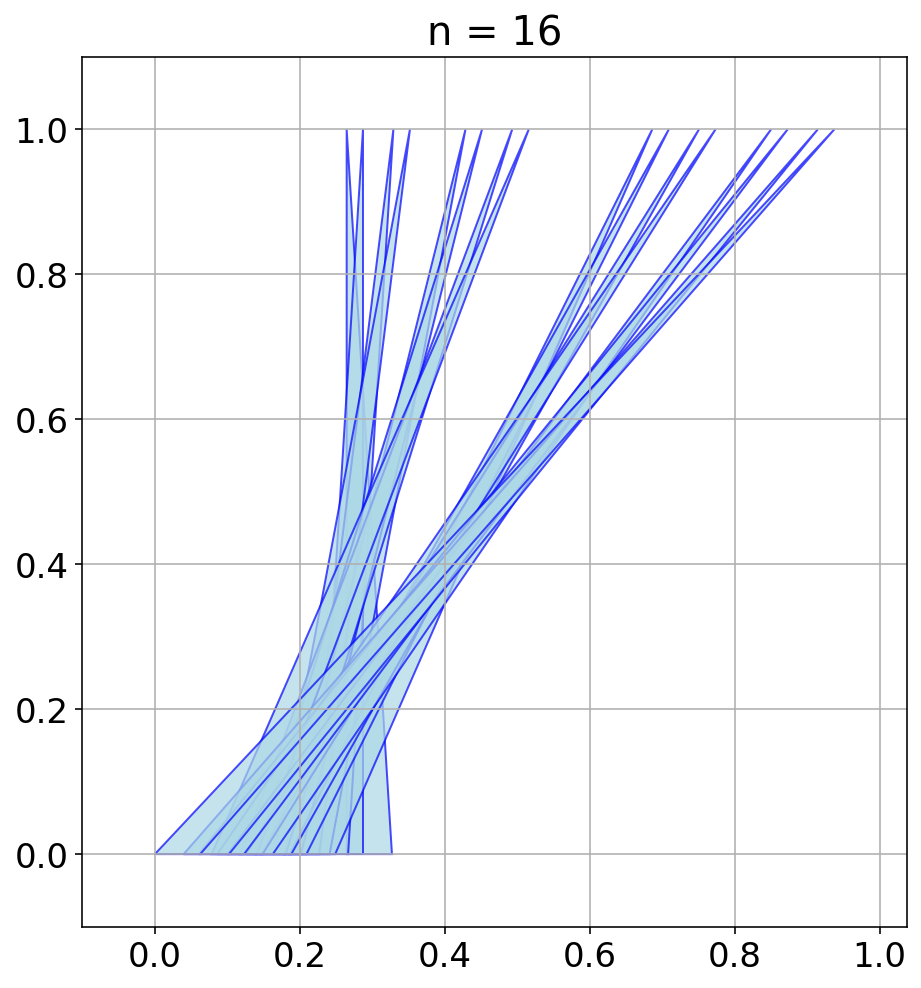

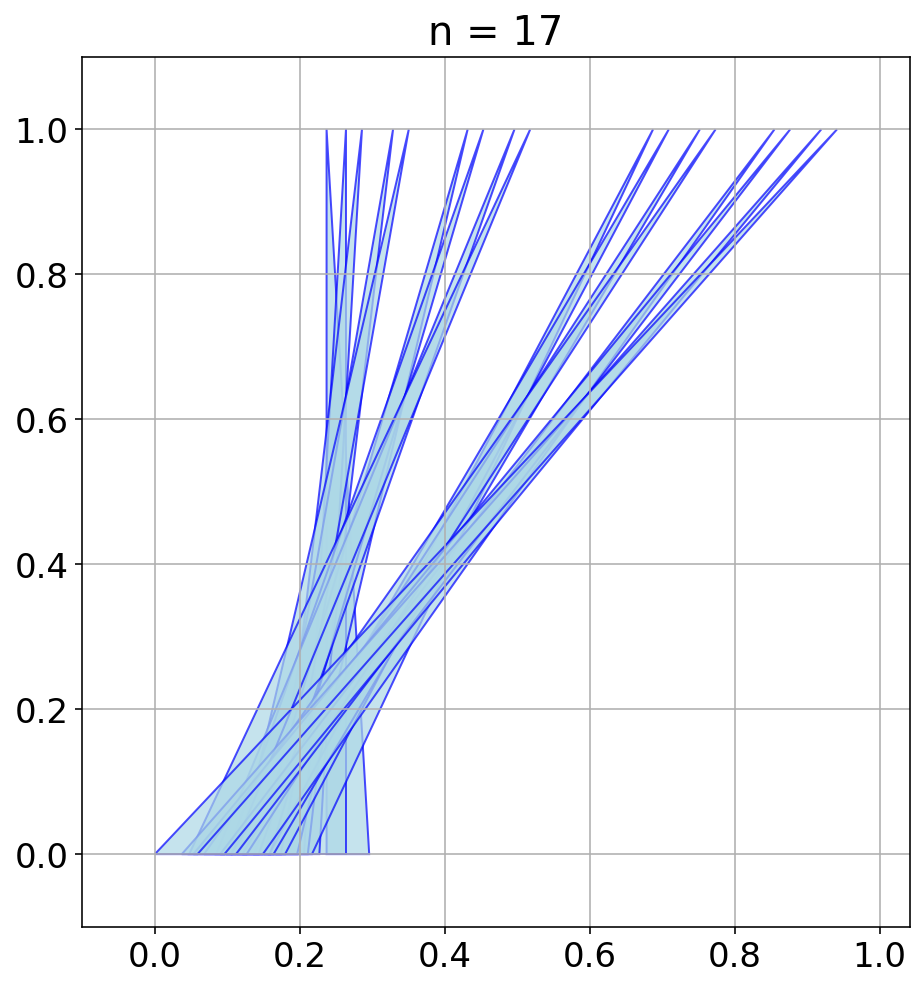

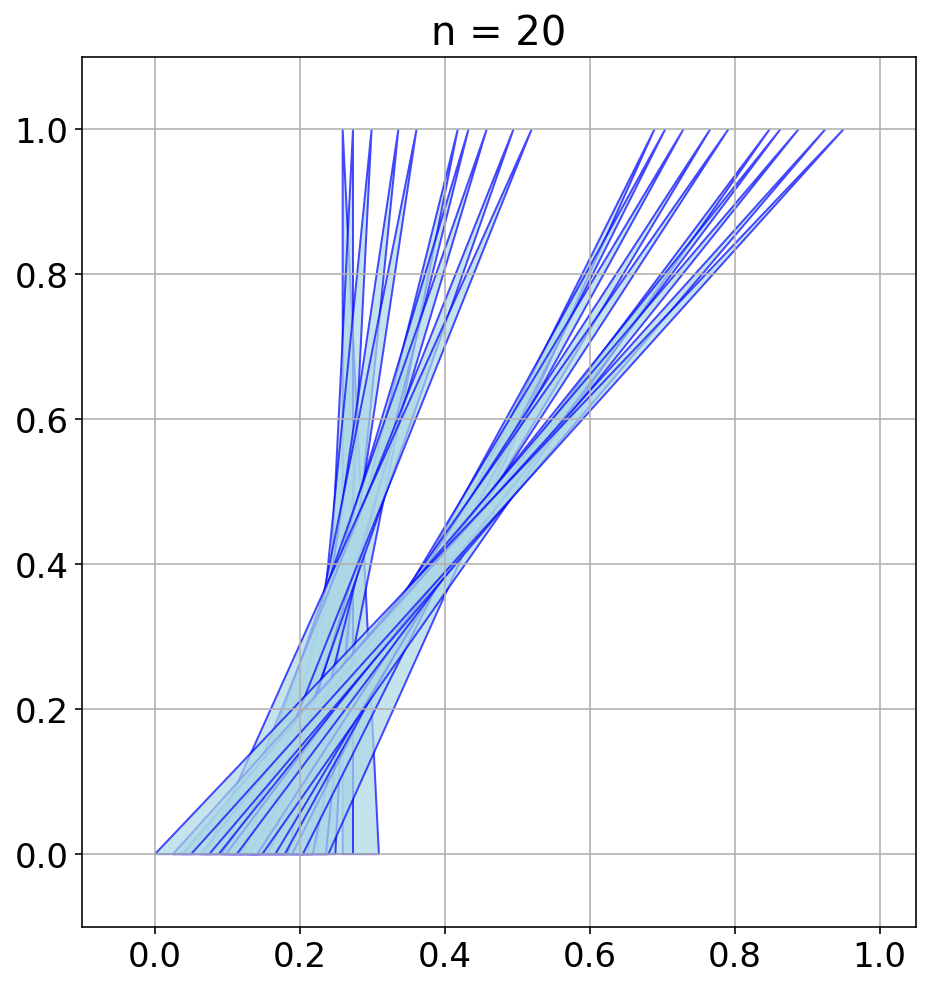

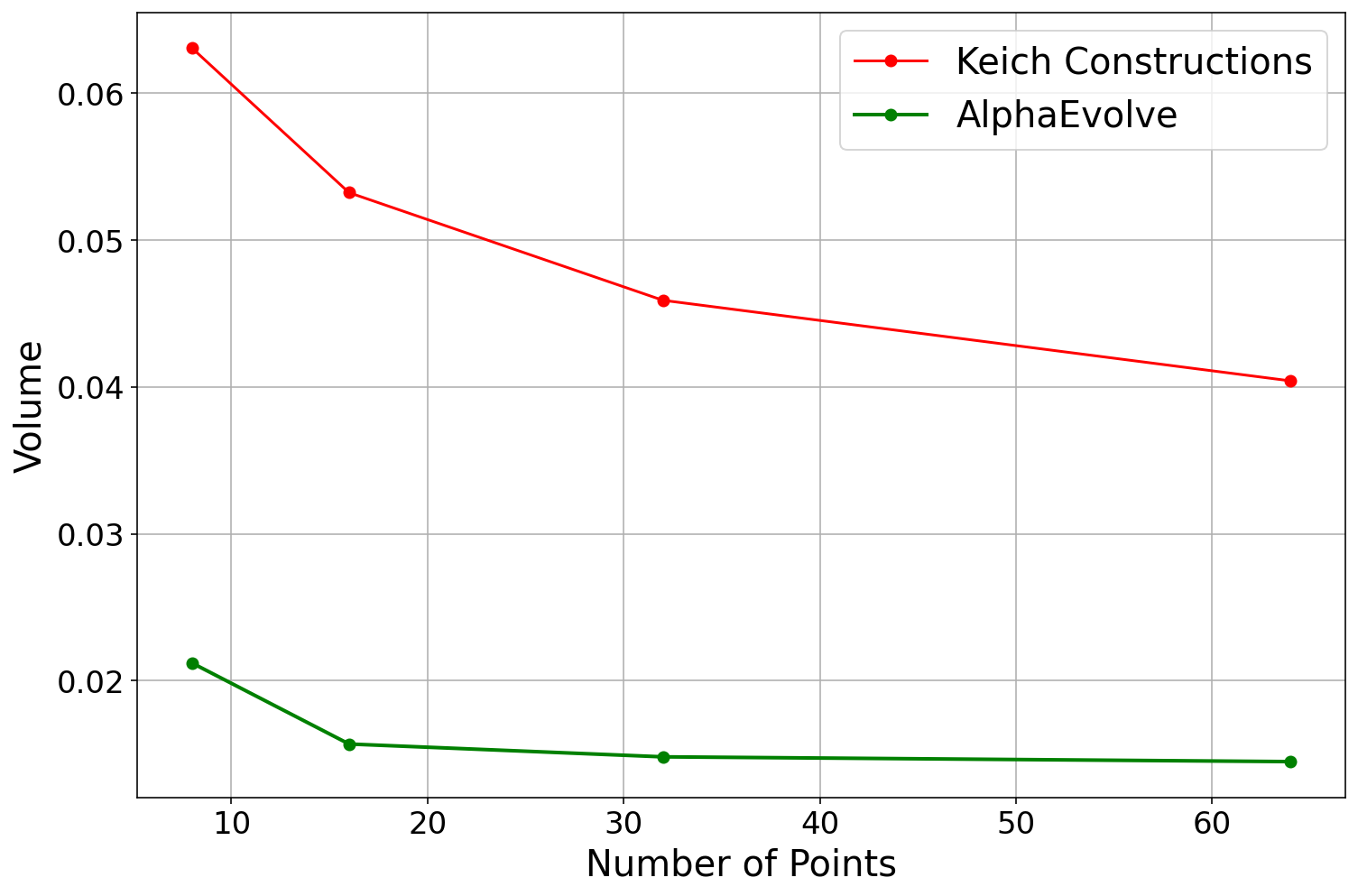

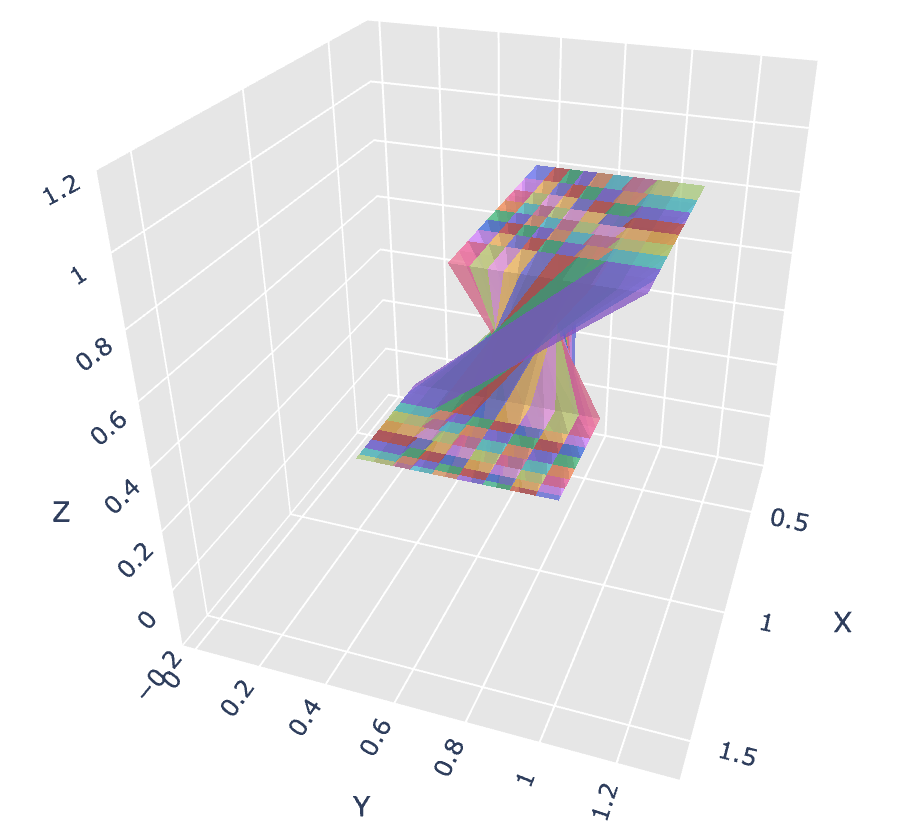

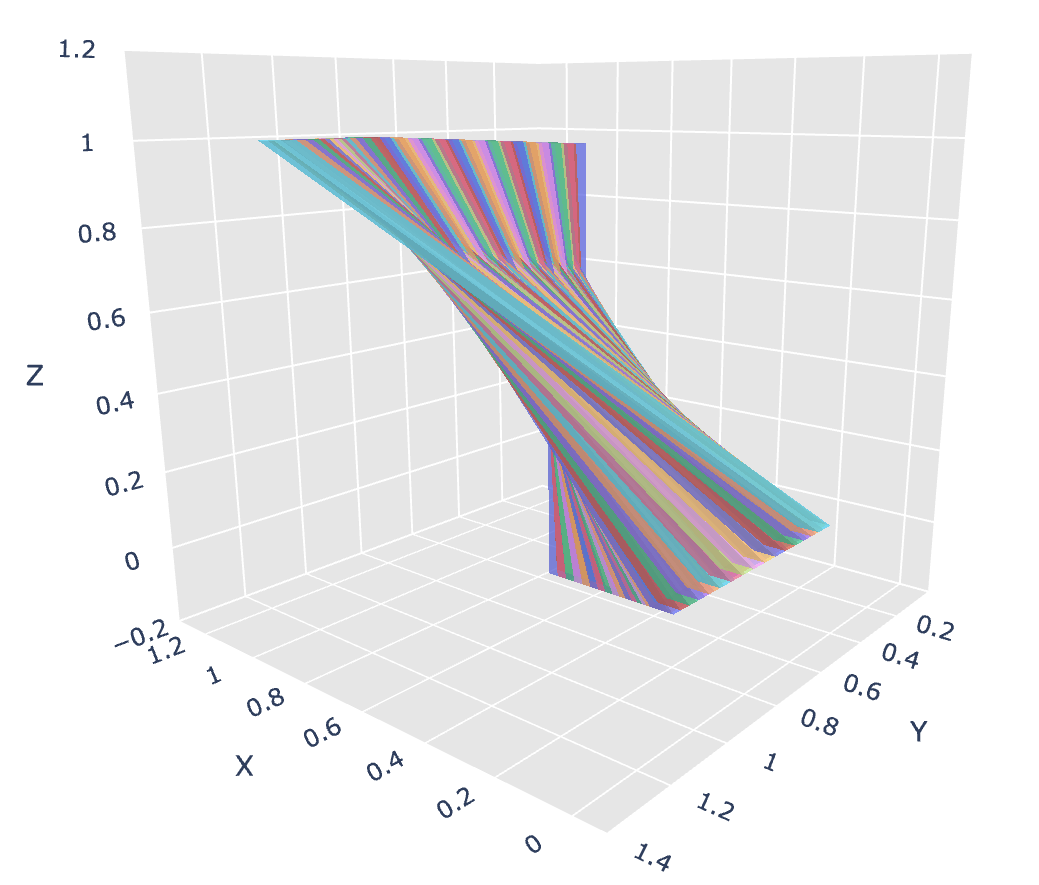

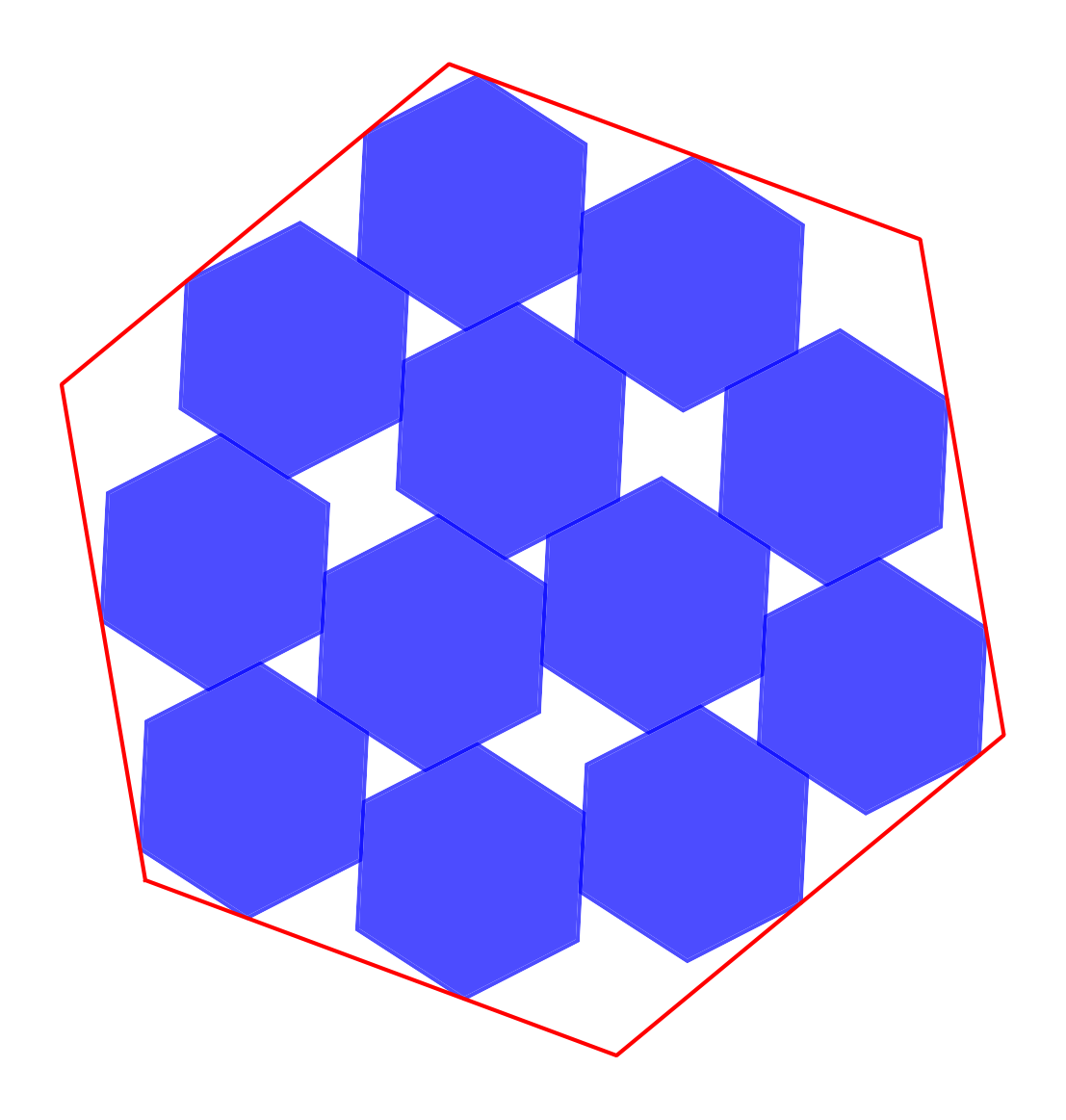

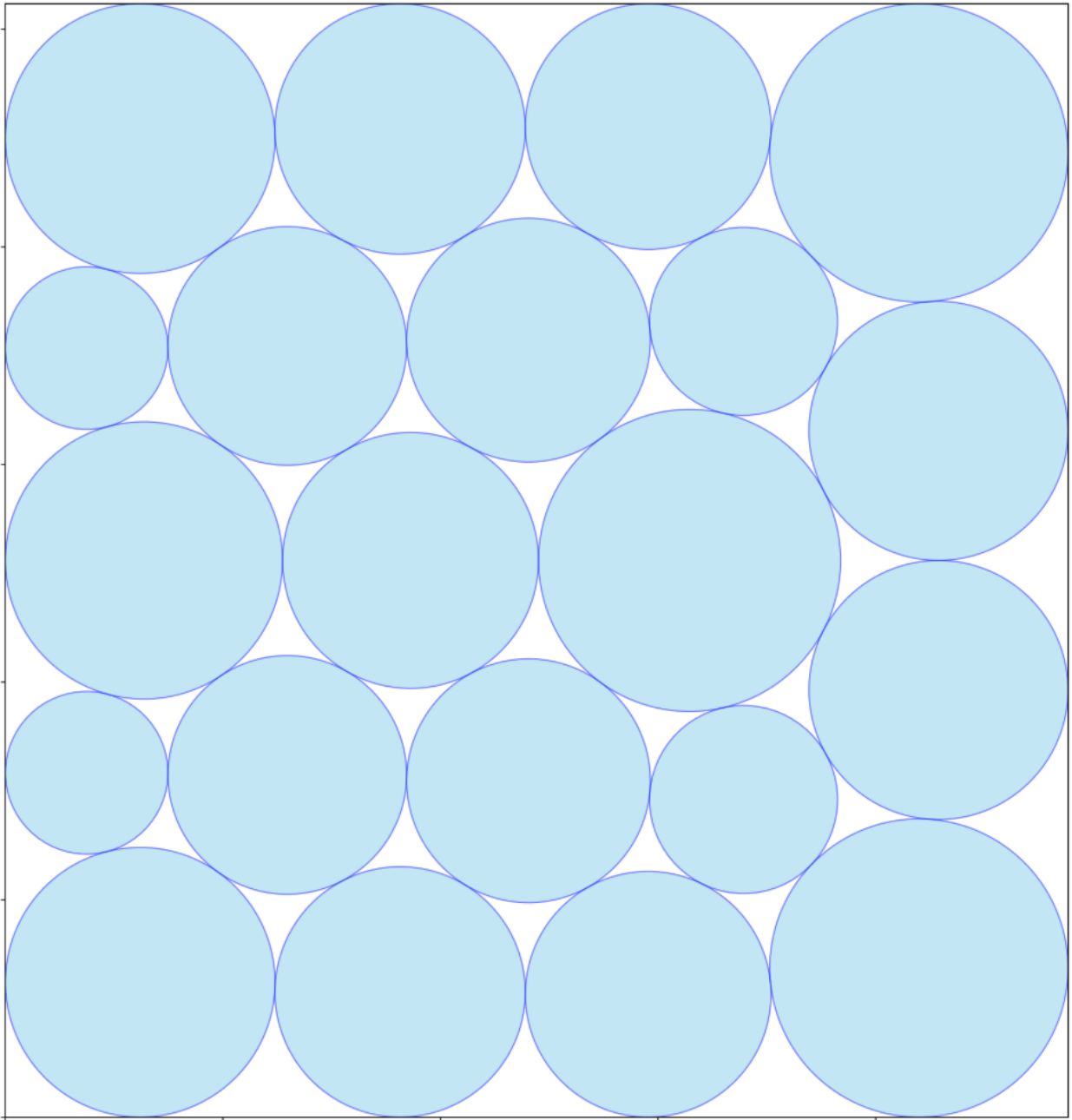

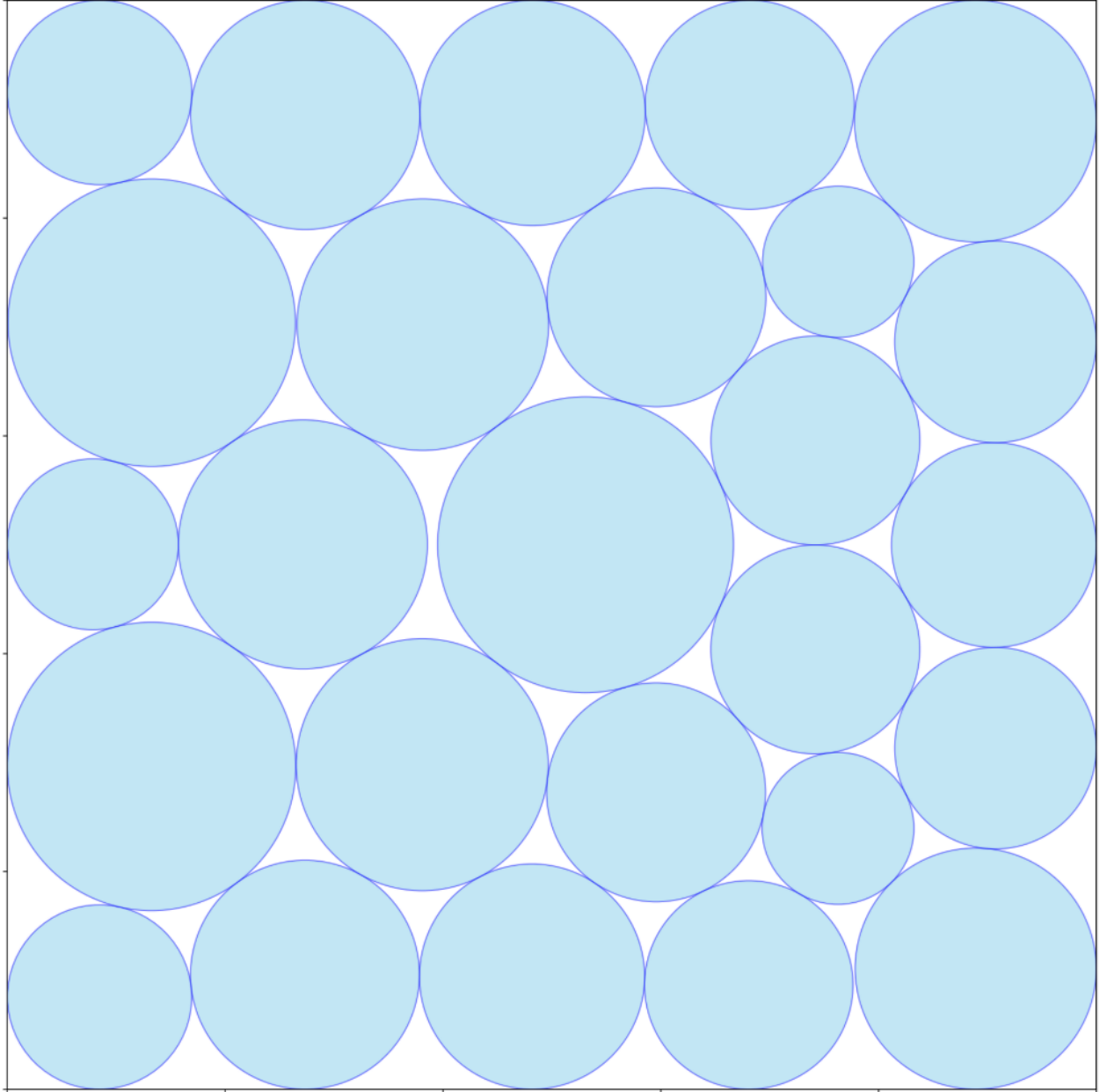

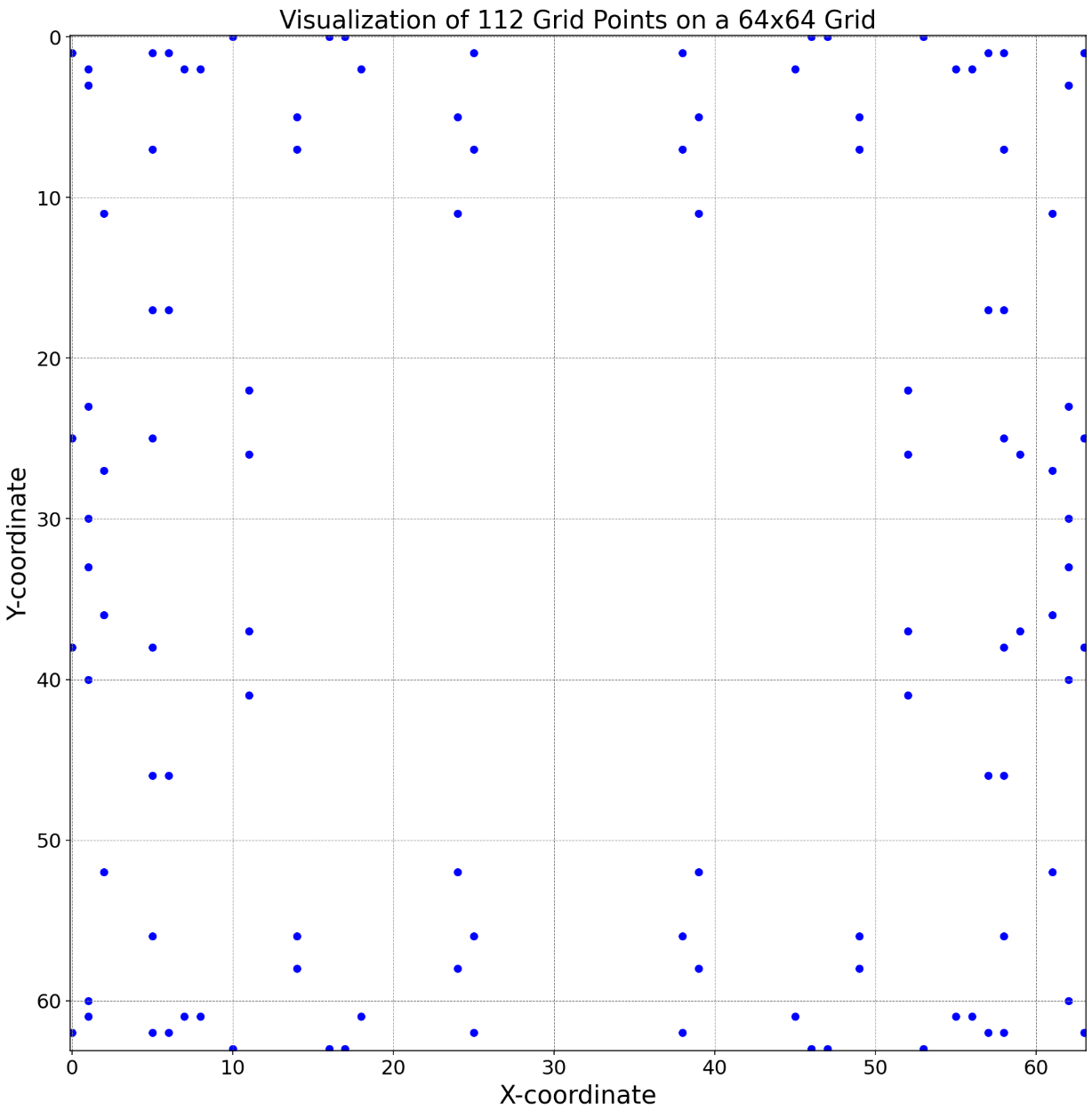

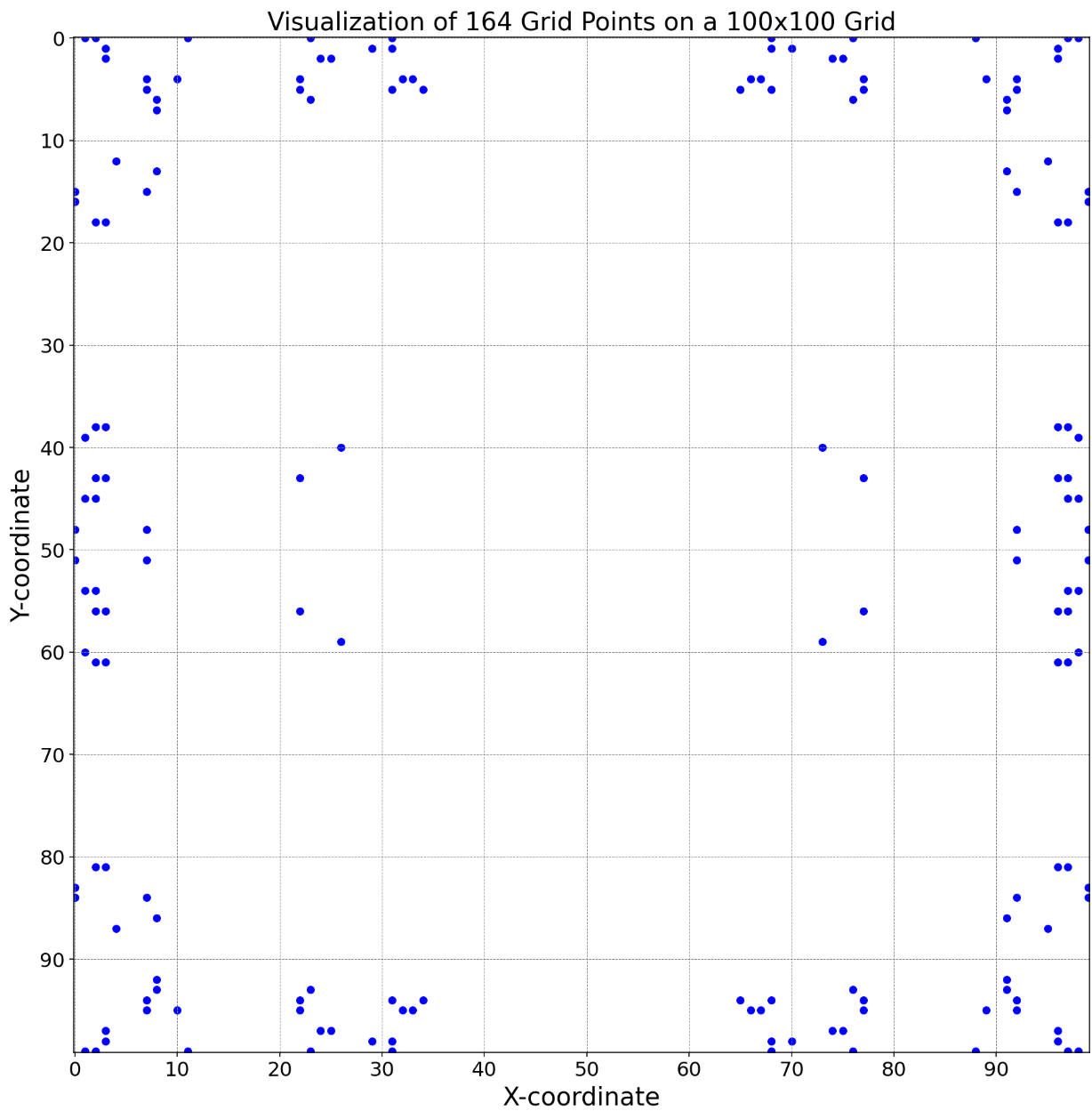

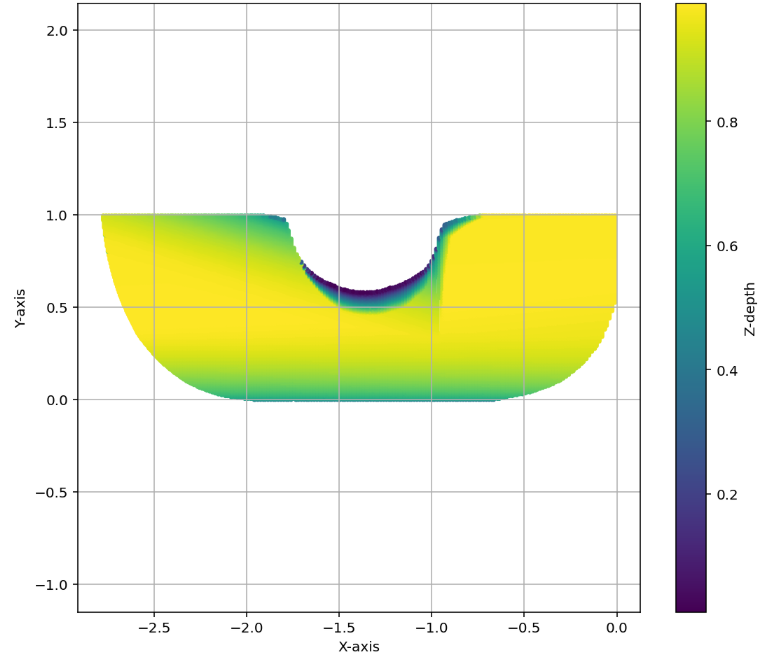

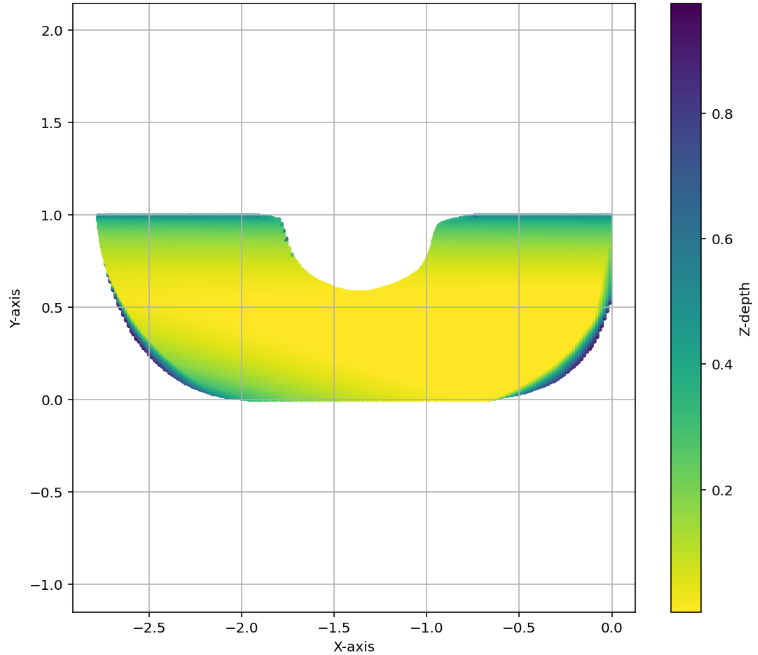

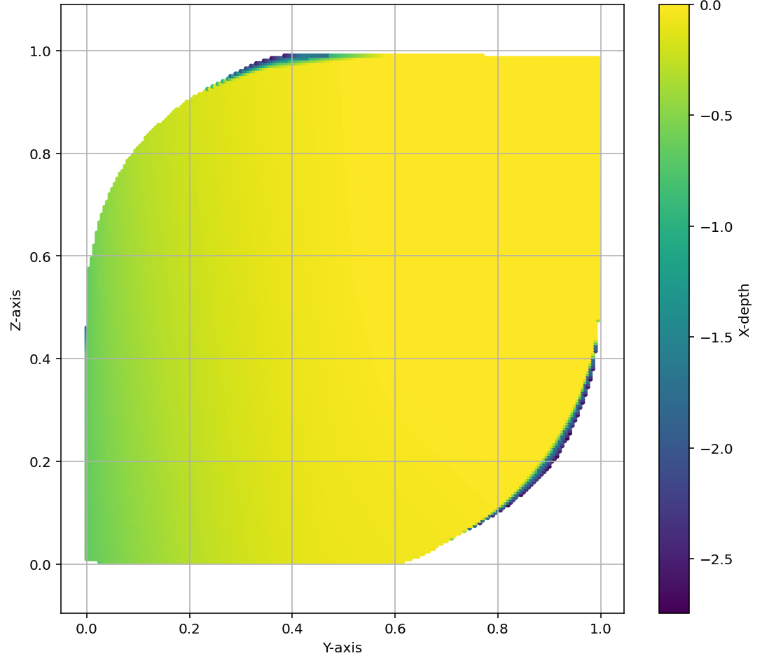

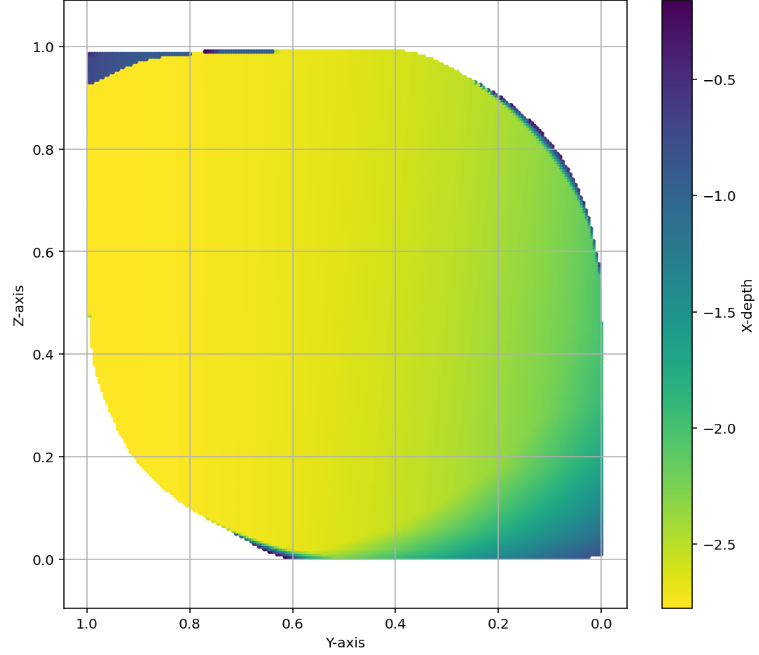

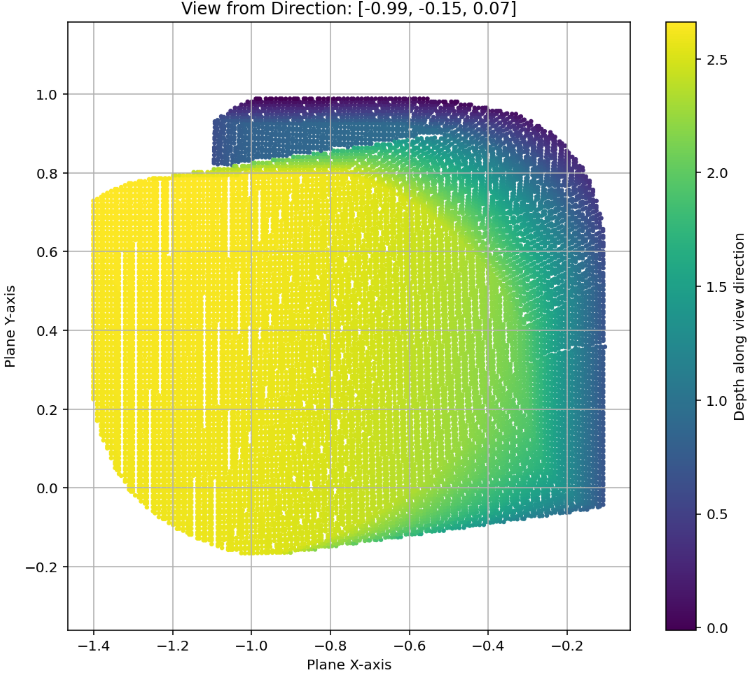

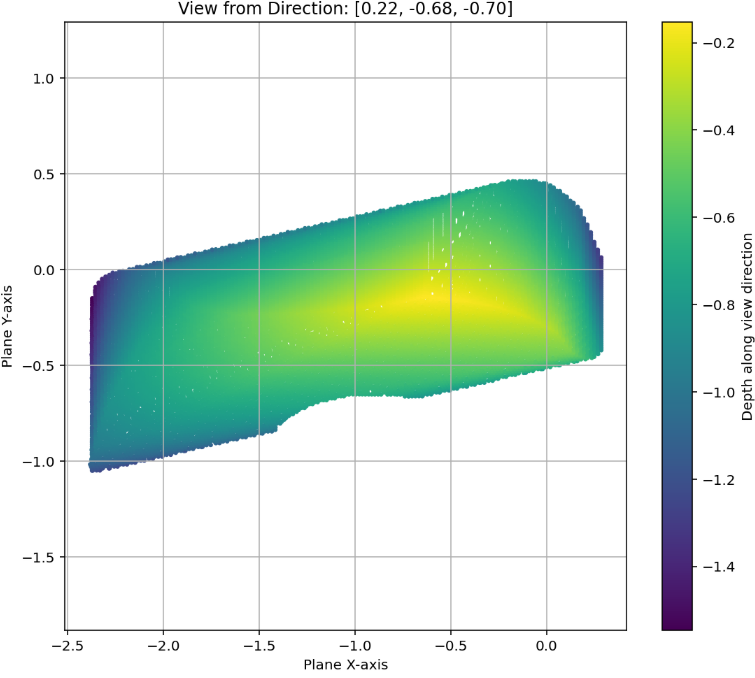

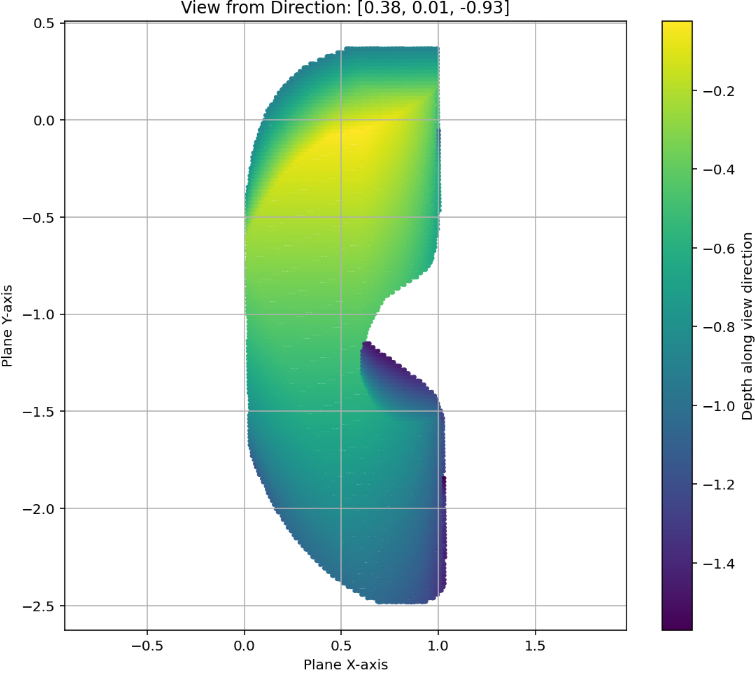

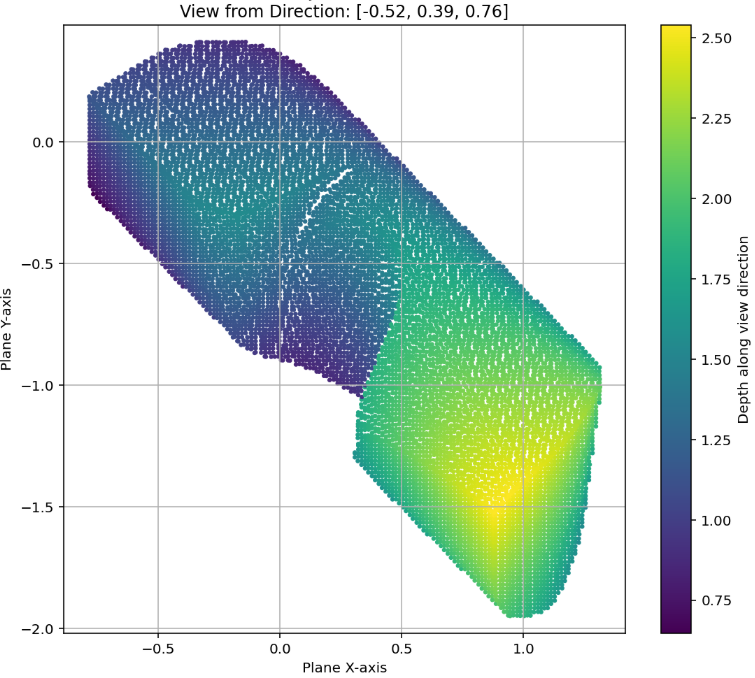

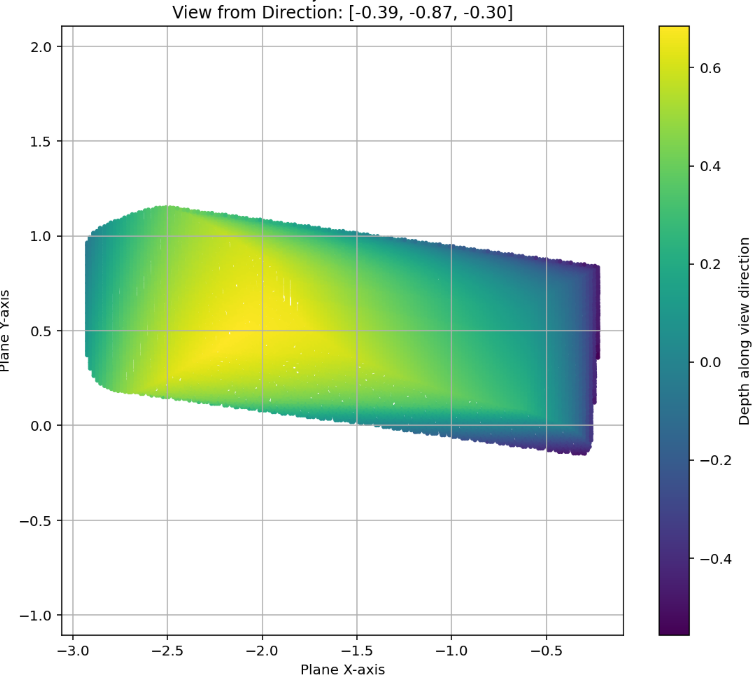

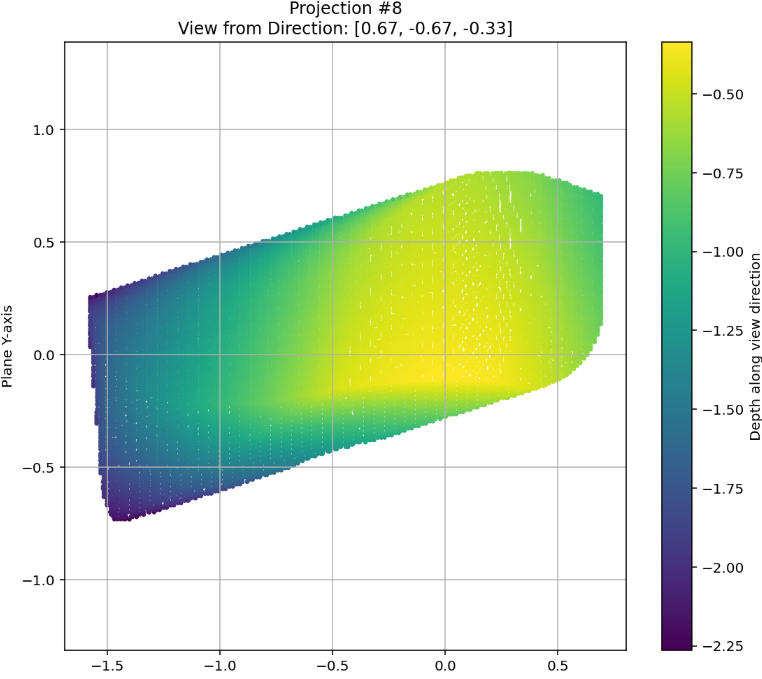

AlphaEvolve could reproduce or improve upon the known upper bounds on and lower bounds on First, we explored the problem in the context of our search mode. We started with the goal to minimize the total union area where we prompted

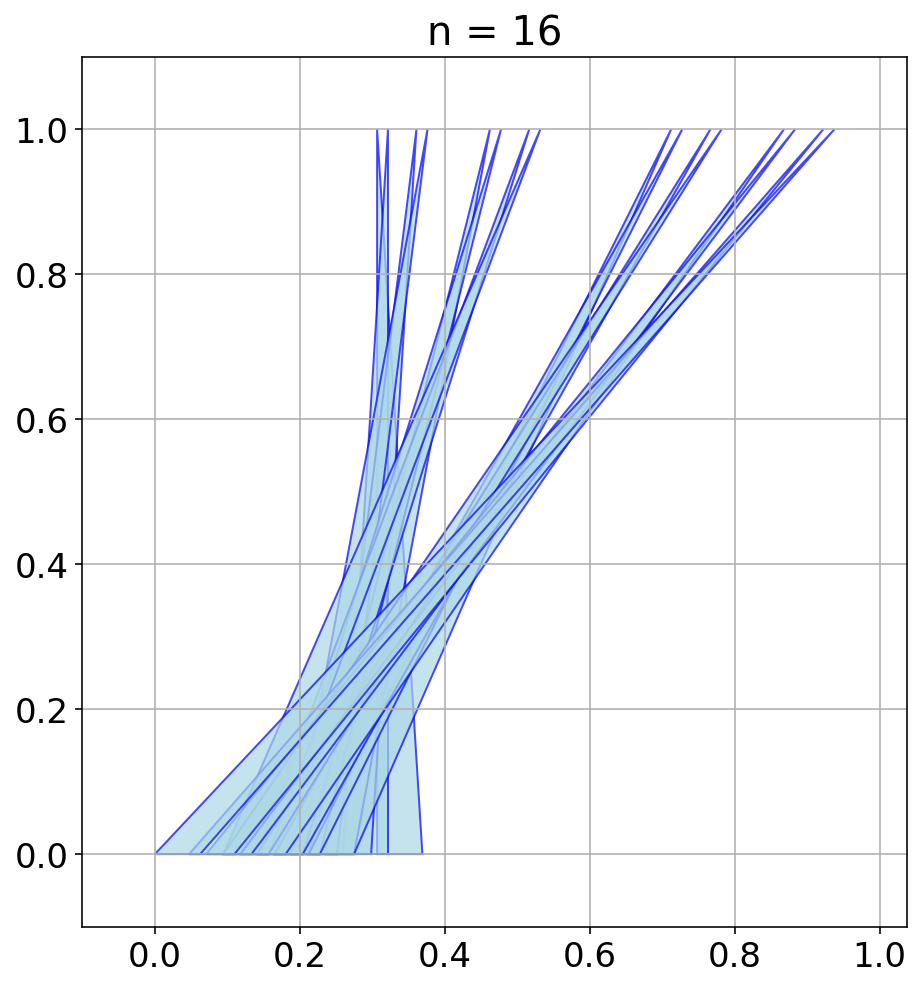

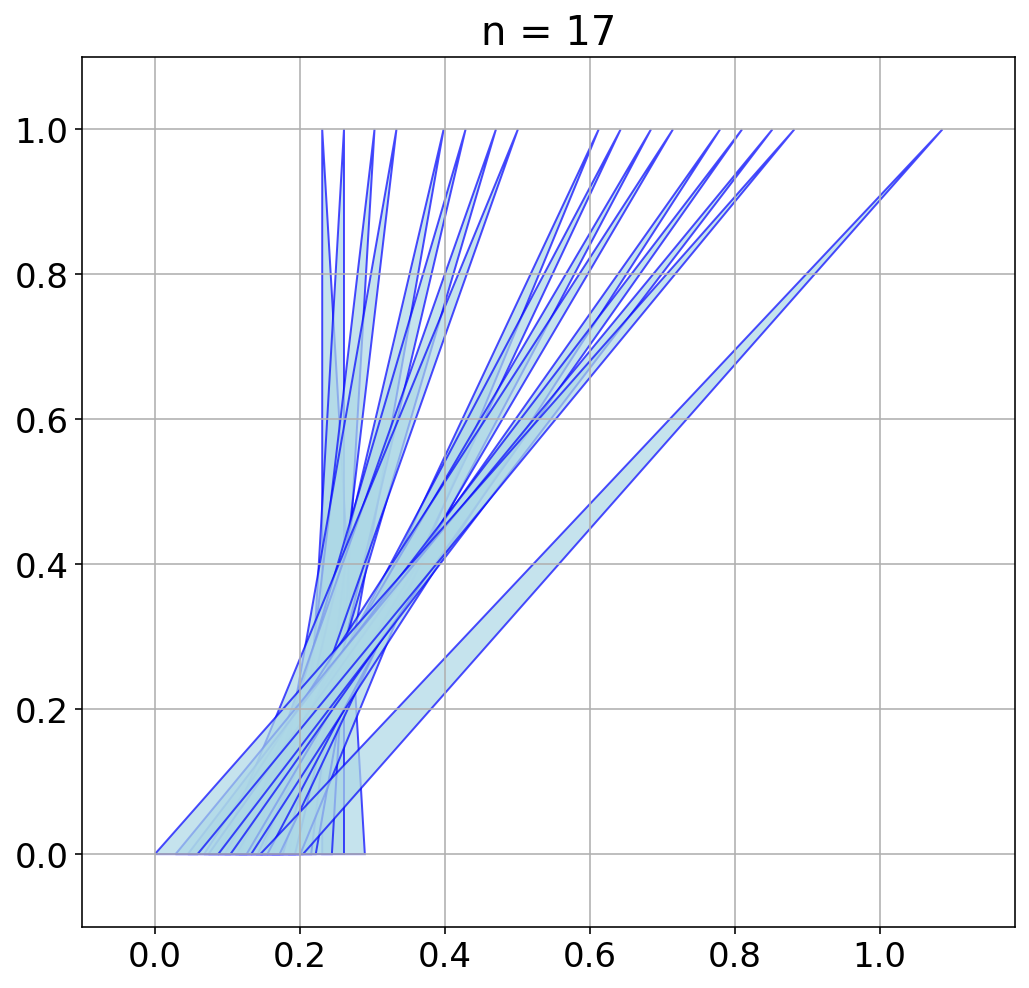

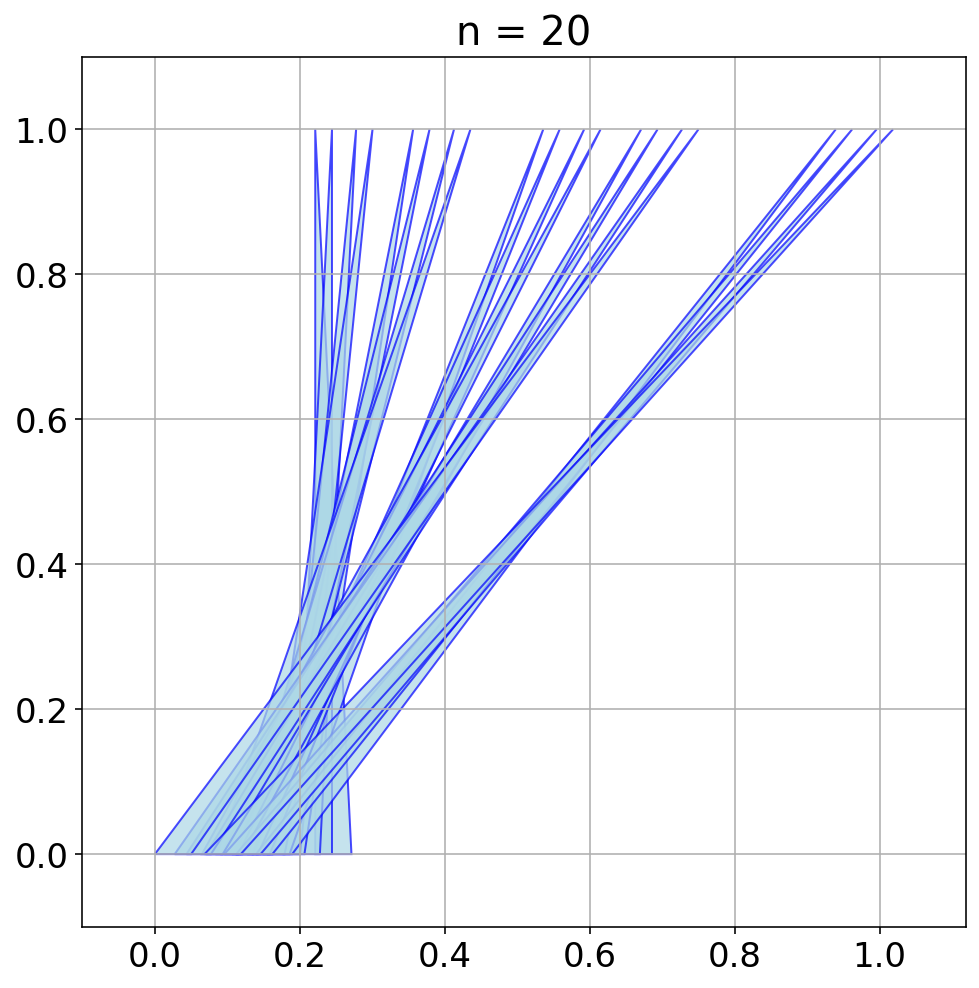

AlphaEvolve with no additional hints or expert guidance. Here AlphaEvolve was expected to evolve a program that given a positive integer returns an optimized sequence of points . Our evaluation computed the total triangle (respectively, parallelogram) area - we used tools from computational geometry such as the shapely library; we also validated the constructions using evaluation from first principles based on Monte Carlo or regular mesh dense sampling to approximate the areas. The areas and scores of several AlphaEvolve constructions are presented in Figure 6. As a guiding baseline we used the construction of Keich [64] which takes to be a power of two, and for expressed in binary as , sets the position to beAlphaEvolve was able to obtain constructions with better union area within 5 to 10 evolution steps (approximately, 1 to 2 hours wall-clock time) - moreover, with longer runtime and guided prompting (e.g. hinting towards patterns in found constructions/programs) we expect that the results for given could be improved even further. Examples of a few of the evolved programs are provided in the Repository of Problems. We present illustrations of constructions obtained by AlphaEvolve in Figures 8 and Figure 9 - curiously, most of the found sets of triangles and polygons visibly have an "irregular" structure in contrast to previous schemes by Keich and Besicovich. While there seems to be some basic resemblance from the distance, the patterns are very different and not self-similar in our case. In an additional experiment we explored further the relationship between the union area and the score whereby we tasked AlphaEvolve to focus on optimizing the score - results are summarized in Figure 7 where we observed an improved performance with respect to Keich's construction.The mentioned results illustrate the ability to obtain configurations of triangles and parallelograms that optimize area/score for a given fixed set of inputs . As a second step we experimented with

AlphaEvolve's ability to obtain generalizable programs - in the prompt we task AlphaEvolve to search for concise, fast, reproducible and human-readable algorithms that avoid black-box optimization. Similarly to other scenarios, we also gave the instruction that the scoring of a proposed algorithm would be done by evaluating its performance on a mixture of small and large inputs and taking the average.At first

AlphaEvolve proposed algorithms that typically generated a collection of from a uniform mesh that is perturbed by some heuristics (e.g. explicitly adjusting the endpoints). Those configurations fell short of the performance of Keich sets, especially in the asymptotic regime as becomes larger. Additional hints in the prompt to avoid such constructions led AlphaEvolve to suggest other algorithms, e.g. based on geometric progressions, that, similarly, did not reach the total union areas of Keich sets for large .In a further experiment we provided a hint in the prompt that suggested Keich's construction as potential inspiration and a good starting point. As a result

AlphaEvolve produced programs based on similar bit-wise manipulations with additional offsets and weighting; these constructions do not assume being a power of 2. An illustration of the performance of such a program is depicted in the top row of Figure 10 - here one observes certain "jumps" in performance around the powers of 2; a closer inspection of the configurations (shown visually in Figure 11) reveals the intuitively suboptimal addition of triangles for . This led us to prompt AlphaEvolve to mitigate this behavior - results of these experiments with improved performance are presented in the bottom row in Figure 10. Examples of such constructions are provided in the Repository of Problems.One can also pose a similar problem in three dimensions:

Problem 10: 3D Kakeya problem

Let . Let denote the minimal volume of prisms with vertices

for some real numbers .

Establish upper and lower bounds for that are as strong as possible.

It is known that

asymptotically as , with the lower bound being a remarkable recent result of Wang and Zahl [65], and the upper bound a forthcoming result of Iqra Altaf2, building on recent work of Lai and Wong [66]. The lower bound is not feasible to reproduce with

AlphaEvolve, but we tested its ability to produce upper bounds.Private communication.

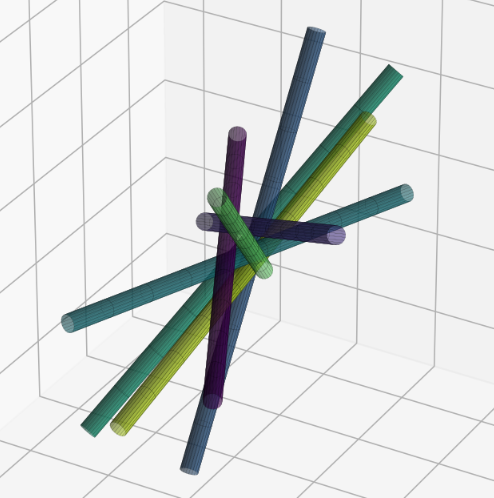

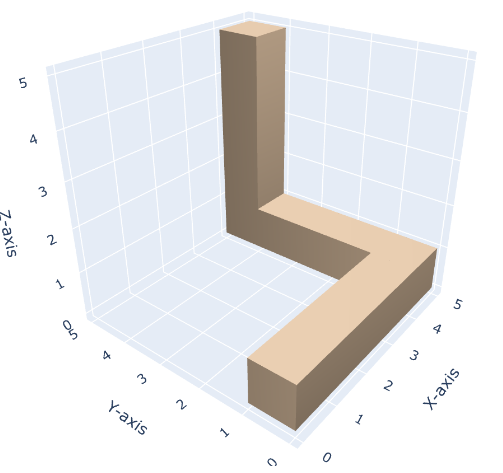

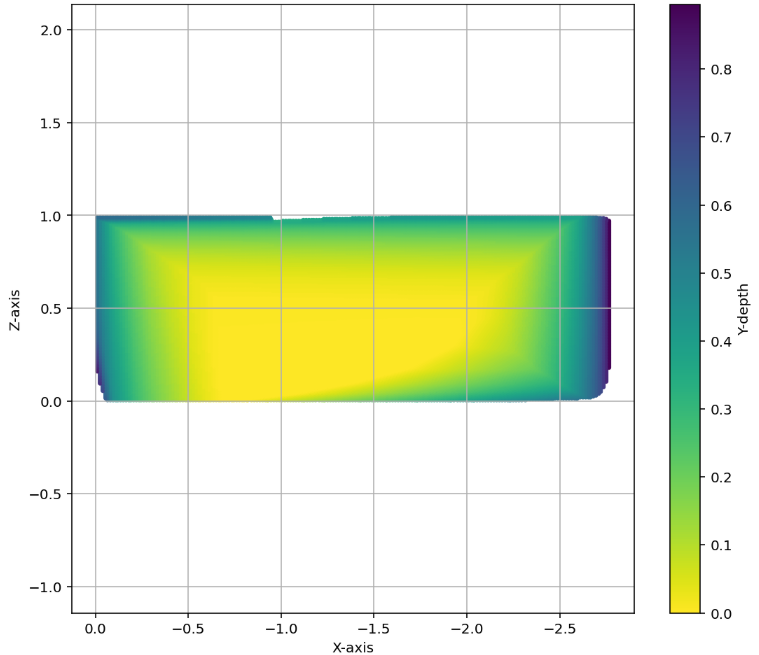

In a similar fashion to the 2D case, we initially explored how the AlphaEvolve

AlphaEvolve search mode could be used to obtain optimized constructions (with respect to volume). The prompt did not contain any specific hints or expert guidance. The evaluation produces an approximation of the volume based on sufficiently dense Monte Carlo sampling (implemented in the 'jaxframework and ran on GPUs) - for the purposes of optimization over a bounded set of inputs (e.g. $n \leq 128$) this setup yields a reasonable and tractable scoring mechanism implemented from first principles. For inputs $n \leq 64$was able to find improvements with respect to Keich's construction - the found volumes are represented in Figure 12; a visualization of theAlphaEvolve` tube placements is depicted in Figure 13.In ongoing work (for both the cases of 2D and higher dimensions) we continue to explore ways of finding better generalizable constructions that would provide further insights for asymptotics as .

6.6 Sphere packing and uncertainty principles

Problem 11: Uncertainty principle

Given a function , set

Let be the largest constant for which one has

for all even with . Establish upper and lower bounds for that are as strong as possible.

Over the last decade several works have explored upper and lower bounds on . For example, in [67] the authors obtained

and established further results in other dimensions. Later on, further improvements in [68] led to and, more recently, in unpublished work by Cohn, de Laat and Gonçalves (announced in [69]) the authors have been able to obtain an upper bound .

One way towards obtaining upper bounds on is based on a linear programming approach - a celebrated instance of which is the application towards sphere packing bounds developed by Cohn and Elkies [70]. Roughly speaking, it is sufficient to construct a suitable auxiliary test function whose largest sign change is as close to as possible. To this end, one can focus on studying normalized families of candidate functions (e.g. satisfying and certain pointwise constraints) parametrized by Fourier eigenbases such as Hermite [67] or Laguerre polynomials [68].

In our framework we prompted

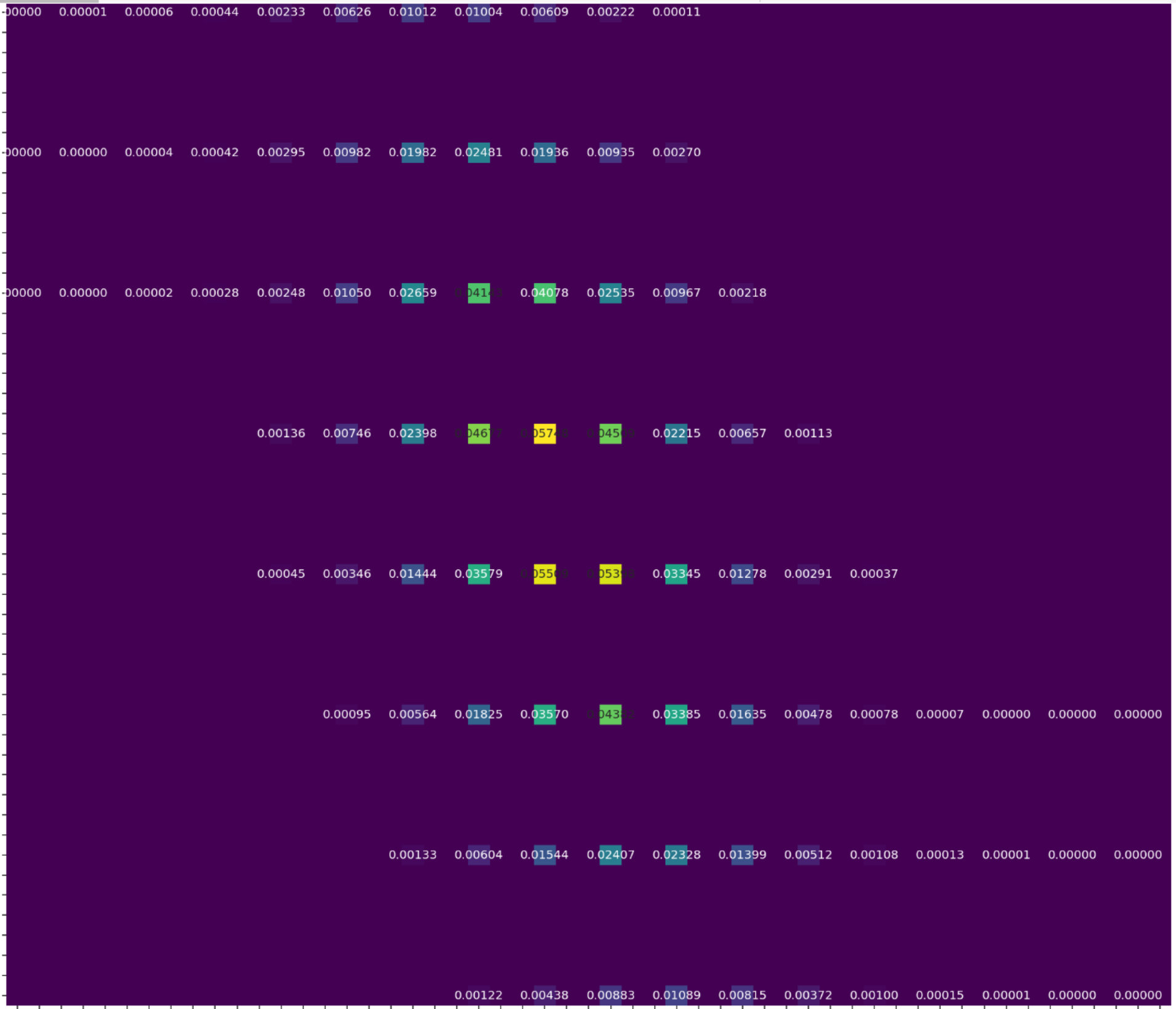

AlphaEvolve to construct test functions of the form where is a linear combination of the polynomial Fourier eigenbasis constrained to ensure that and . We experimented using both the Hermite and Laguerre approaches: in the case of Hermite polynomials AlphaEvolve specified the coefficients in the linear combination ([67]) whereas for Laguerre polynomials the setup specified the roots ([68]). From another perspective, the search for optimal polynomials is an interesting benchmark for AlphaEvolve since there exists a polynomial-time search algorithm that becomes quite expensive as the degrees of the polynomials grow.For a given size of the linear combination we employed our search mode that gives

AlphaEvolve a time budget to design a search strategy making use of the corresponding scoring function. The scoring function (verifier) estimated the last sign change of the corresponding test function. Additionally, we explored tradeoffs between the speed and accuracy of the verifiers - a fast and less accurate (leaky) verifier based on floating point arithmetic and a more reliable but slower verifier written using rational arithmetic.As reported in [1],

AlphaEvolve was able to obtain a refinement of the configuration in [67] using a linear combination of three Hermite polynomials with coefficients yielding an upper bound . Furthermore, using the Laguerre polynomial formulation (and prompting AlphaEvolve to search over the positions of double roots) we obtained the following constructions and upper bounds on ::Table 3: Prescribed double roots for different values of with corresponding bounds

We remark that these estimates do not outperform the state of the art announced in [69] - interestingly, the structure of the maximizer function the authors propose suggests it is not analytic; this might require a different setup for

AlphaEvolve than the one above based on double roots. However, the bounds in Table 3 are competitive with respect to prior bounds e.g. in [68] - moreover, an advantage of AlphaEvolve we observe here is the efficiency and speed of the experimental work that could lead to a good bound.As alluded to above, there exists a close connection between these types of uncertainty principles and estimates on sphere packing - this is a fundamental problem in mathematics, open in all dimensions other than [71,72,73,74].

Problem 12: Sphere packing

For any dimension , let denote the maximal density of a packing of by unit spheres. Establish upper and lower bounds on that are as strong as possible.

Problem 13: Linear programming bound

For any dimension , let denote the quantity

where ranges over integrable continuous functions , not identically zero, with for all and for all for some . Establish upper and lower bounds on that are as strong as possible.

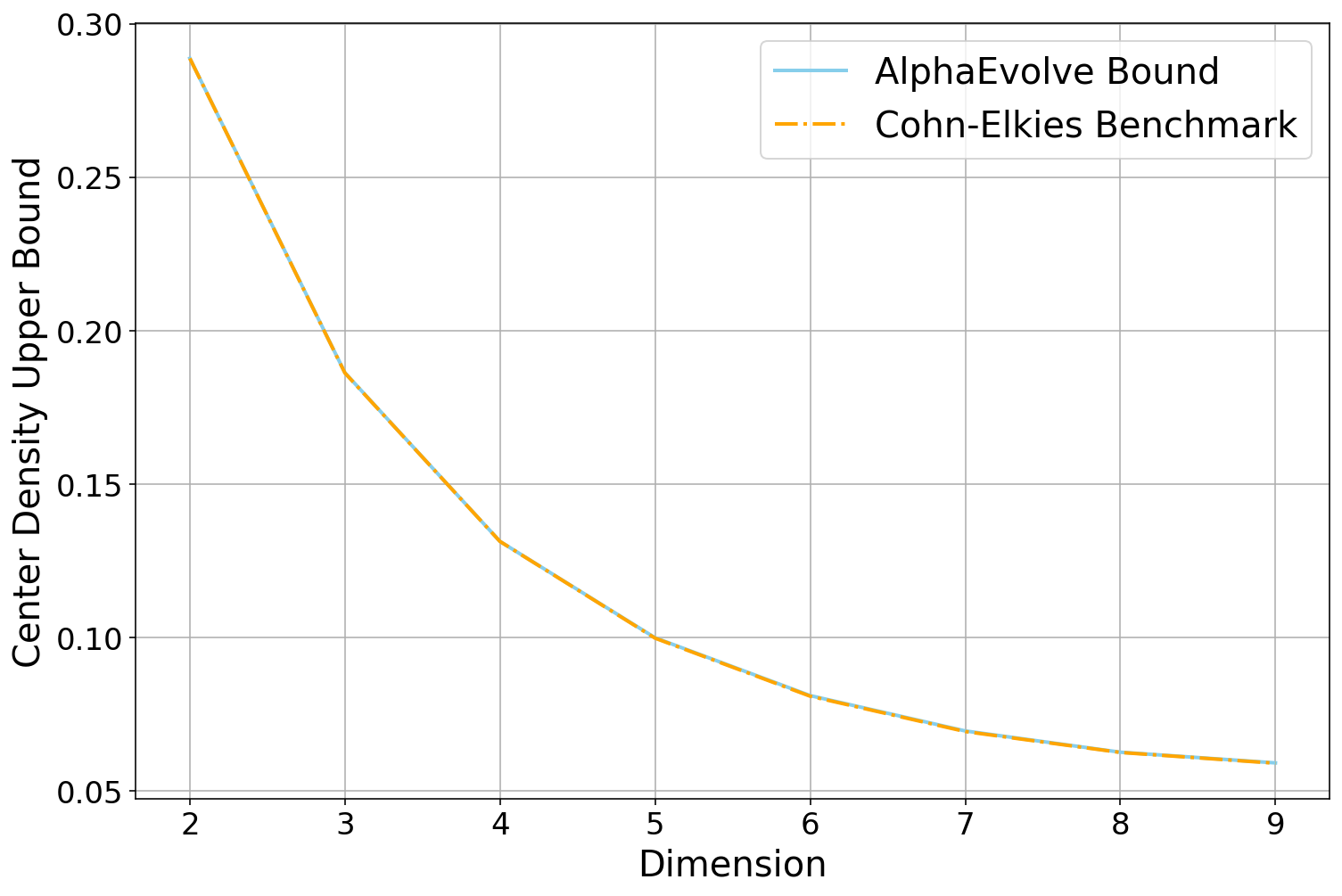

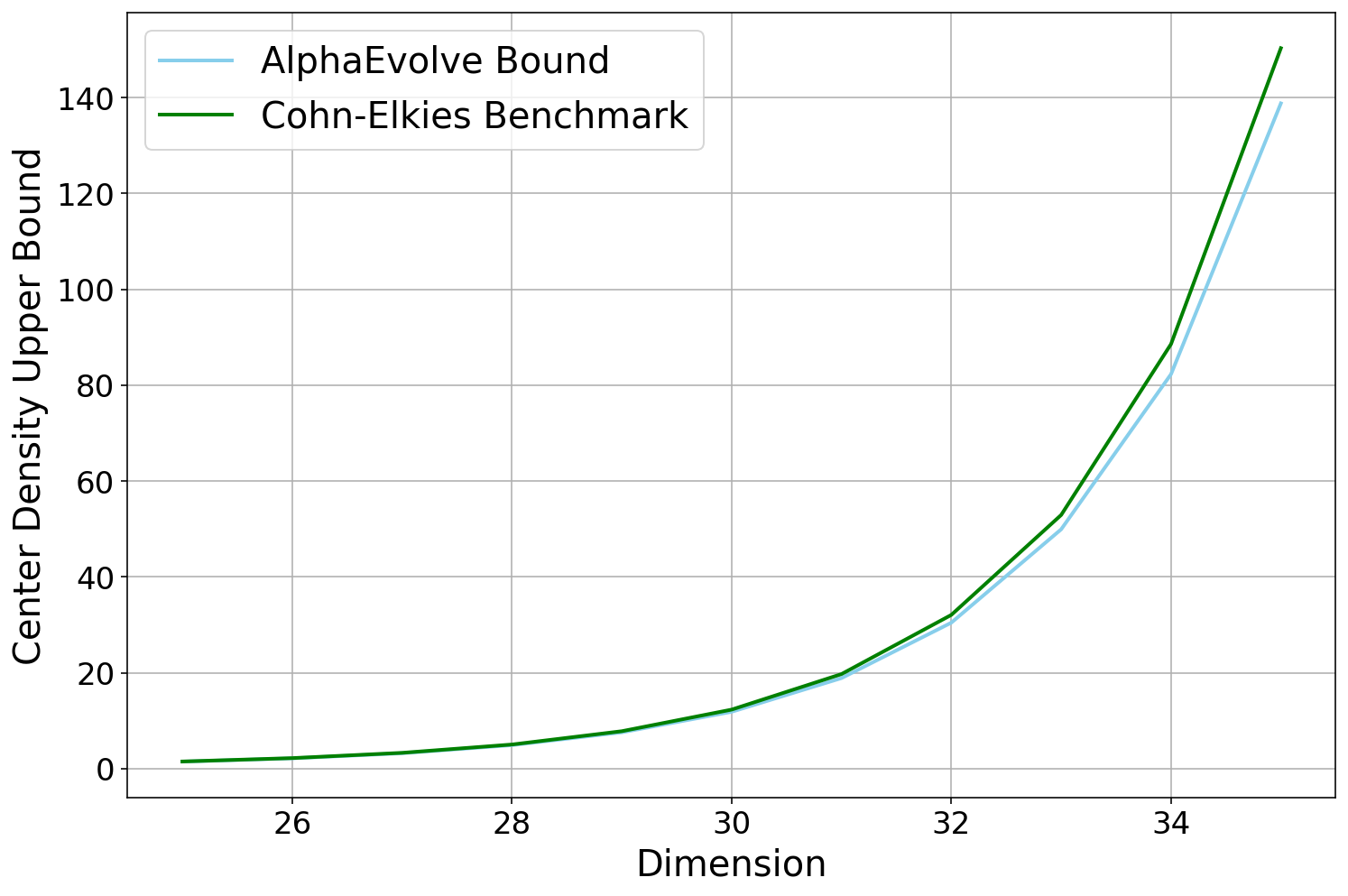

It was shown in [70] that , thus upper bounds on give rise to upper bounds on the sphere packing problem. Remarkably, this bound is known to be tight for (with extremizer and in the case), although it is not believed to be tight for other values of . Additionally, the problem has been extensively studied numerically with important baselines presented in [70].

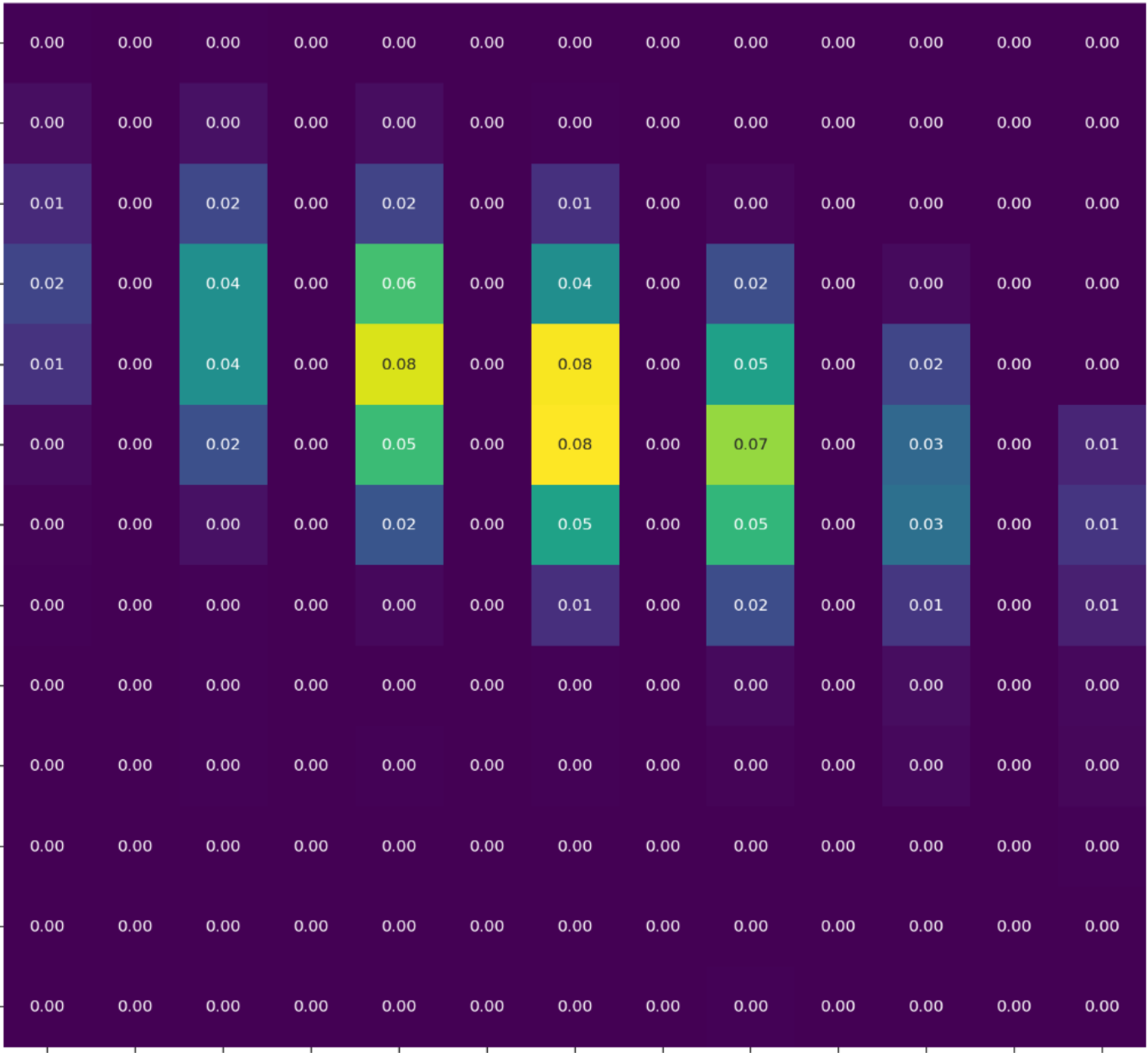

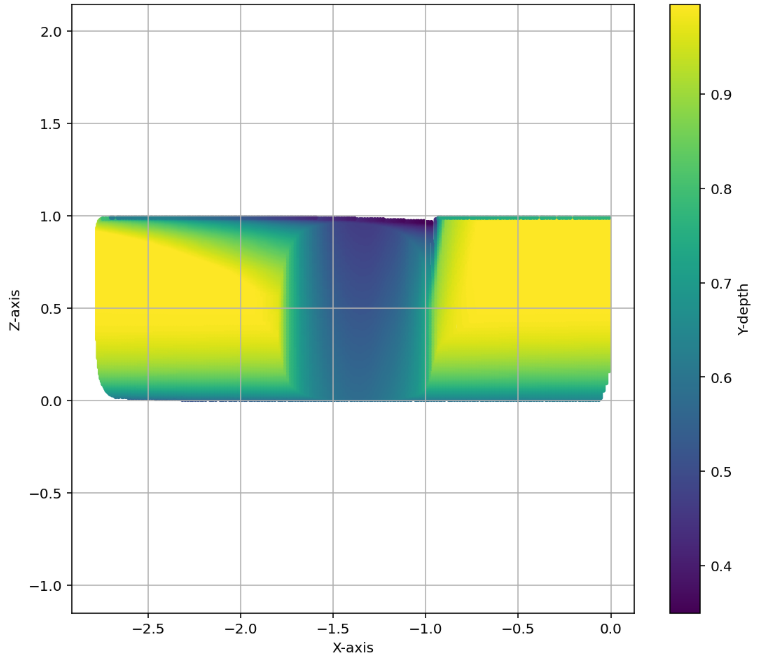

Upper bounds for can be obtained by exhibiting a function for which both and have a tractable form that permits the verification of the constraints stated in Problem 13, and thus a potential use case for

AlphaEvolve. Following the approach of Cohn and Elkies [70], we represent as a spherically symmetric function that is a linear combination of Laguerre polynomials times a gaussian, specifically of the formwhere are real coefficients and . In practice it was helpful to force to have single and double roots at various locations that one optimizes in. We had to resort to extended precision and rational arithmetic in order to define the verifier; see Figure 14.

An additional feature in our experiments here is given by the reduced effort to prepare a numerical experiment that would produce a competitive bound - one only needs to prepare the verifier and prompt (computing the estimate of the largest sign change given a polynomial linear combination) leaving the optimization schemes to be handled by

AlphaEvolve. In summary, although so far AlphaEvolve has not obtained qualitatively new state-of-the-art results, it demonstrated competitive performance when instructed and compared against similar optimization setups from the literature.6.7 Classical inequalities

As a benchmark for our setup, we explored several scenarios where the theoretical optimal bounds are known [75,76] - these include the Hausdorff--Young inequality, the Gagliardo--Nirenberg inequality, Young's inequality, and the Hardy-Littlewood maximal inequality.

Problem 14: Hausdorff–Young

For , let be the best constant such that

holds for all test functions . Here is the dual exponent of . What is ?

It was proven by Beckner [77] (with some special cases previously worked out in [78]) that

The extremizer is obtained by choosing to be a Gaussian.

We tested the ability for

AlphaEvolve to obtain an efficient lower bound for by producing code for a function with the aim of extremizing Equation 5. Given a candidate function proposed by AlphaEvolve, the corresponding evaluator estimates the ratio using a step function approximation of . More precisely, for truncation parameters and discretization parameter , we work with an explicitly truncated discretized version of , e.g., the piecewise constant approximationIn particular, in this representation is compactly supported, the Fourier transform is an explicit trigonometric polynomial and the numerator of could be computed to a high precision using a Gaussian quadrature.

Being a well-known result in analysis, we experimented designing various prompts where we gave

AlphaEvolve different amounts of context about the problem as well as the numerical evaluation setup, i.e. the approximation of via and the option to allow AlphaEvolve to choose the truncation and discretization parameters . Furthermore, we tested several options for where ranged over . In all cases the setup guessed the Gaussian extremizer either immediately or after one or two iterations, signifying the LLM's ability to recognize and recall its relation to Hausdorff--Young's inequality. This can be compared with more traditional optimization algorithms, which would produce a discretized approximation to the Gaussian as the numerical extremizer, but which would not explicitly state the Gaussian structure.Problem 15: Gagliardo–Nirenberg

Let , and let and be non-negative integers such that . Furthermore, let be real and such that the following relations hold:

Let be the best constant such that

for all test functions , where denotes the derivative operator . Then is finite. Establish lower and upper bounds on that are as strong as possible.

To reduce the number of parameters, we only considered the following variant:

Problem 16: Special case of Gagliardo–Nirenberg

Let . Let denote the supremum of the quantities

for all smooth rapidly decaying , not identically zero. Establish upper and lower bounds for that are as strong as possible.

A brief calculation shows that

Clearly one can obtain lower bounds on by evaluating at specific . It is known that is extremized when is the hyperbolic secant function [79], thus allowing for to be computed exactly. In our setup

AlphaEvolve produces a one-dimensional real function where one can compute for every - to evaluate numerically we approximate a given candidate by using piecewise linear splines. Similarly to the Hausdorff--Young outcome, we experimented with several options for in and in each case AlphaEvolve guessed the correct form of the extremizer in at most two iterations.Problem 17: Young's convolution inequality

Let with . Let denote the supremum of the quantity

over all non-zero test functions . What is ?

It is known [77] that is extremized when are Gaussians (see [77]) which satisfy . Thus, we have

We tested the ability of

AlphaEvolve to produce lower bounds for , by prompting AlphaEvolve to propose two functions that optimize the quotient keeping the prompting instructions as minimal as possible. Numerically, we kept a similar setup as for the Hausdorff--Young inequality and work with step functions and discretization parameters. AlphaEvolve consistently came up with the following pattern that proceeds in the following three steps: (1) propose two standard Gaussians as a first guess; (2) Introduce variations by means of parameters such as ; (3) Introduce an optimization loop that numerically fine-tunes the parameters before defining - in most runs these are based on gradient descent that optimizes in terms of the parameters . After the optimization loop one obtains the theoretically optimal coupling between the parameters.We remark again that in most of the above runs

AlphaEvolve is able to almost instantly solve or guess the correct structure of the extremizers highlighting the ability of the system to recover or recognize the scoring function.Next, we evaluated

AlphaEvolve against the (centered) one-dimensional Hardy--Littlewood inequality.Problem 18: Hardy–Littlewood maximal inequality

Let denote the best constant for which

for absolutely integrable non-negative . What is ?

This problem was solved completely in [80,81], which established

Both the upper and lower bounds here were non-trivial to obtain; in particular, natural candidate functions such as Gaussians or step functions turn out not to be extremizers.

We use an equivalent form of the inequality which is computationally more tractable: is the best constant such that for any real numbers and , one has

(with the convention that is empty for ; see ([80], Lemma 1)).

For instance, setting we have

leading to the lower bound . If we instead set and then we have

leading to for all . In fact, for some time it had been conjectured that was until a tighter lower bound was found by Aldaz; see [82].

In our setup we prompted

AlphaEvolve to produce two sequences that respect the above negativity and monotonicity conditions and maximize the ratio between the left-hand and right-hand sides of the inequality. Candidates of this form serve to produce lower bounds for . As an initial guess AlphaEvolve started with a program that produced suboptimal and yielded lower bounds less than .AlphaEvolve was tested using both our search and generalization approaches. In terms of data contamination, we note that unlike other benchmarks (such as e.g. the inequalities of Hausdorff--Young or Gagliardo--Nirenberg) the underlying large language models did not seem to draw direct relations between the quotient and results in the literature related to the Hardy--Littlewood maximal inequality.In the search mode

AlphaEvolve was able to obtain a lower bound , surpassing the barrier but not fully reaching . The construction of found by AlphaEvolve was largely based on heuristics coupled with randomized mutation of the sequences and large-scale search. Regarding the generalization approach, AlphaEvolve swiftly obtained the bound using the argument above. However, further improvement was not observed without additional guidance in the prompt. Giving more hints (e.g. related to the construction in [82]) led AlphaEvolve to explore more configurations where are built from shorter, repeated patterns - the obtained sequences were essentially variations of the initial hints leading to improvements up to .6.8 The Ovals problem

Problem 19: Ovals problem

Let denote the infimal value of , the least eigenvalue of the Schrödinger operator

associated with a simple closed convex curve parameterized by arclength and normalized to have length , where is the curvature.

Obtain upper and lower bounds for that are as strong as possible.

Benguria and Loss [83] showed that determines the smallest constant in a one-dimensional Lieb--Thirring inequality for a Schrödinger operator with two bound states, and showed that

with the upper bound coming from the example of the unit circle, and more generally on a two-parameter family of geometrically distinct ovals containing the round circle and collapsing to a multiplicity-two line segment. The quantity was also implicitly introduced slightly earlier by Burchard and Thomas in their work on the local existence for a dynamical Euler elastica [84]. They showed that , which is in fact optimal if one allows curves to be open rather than closed; see also [85].

It was conjectured in [83] that the upper bound was in fact sharp, thus . The best lower bound was obtained by Linde [86] as . See the reports [87,88] for further comments and strategies on this problem.

We can characterize this eigenvalue in a variational way. Given a closed curve of length , parametrized by arclength with curvature , then

The eigenvalue problem can be phrased as the variational problem:

where and are Sobolev spaces.

In other words, the problem of upper bounding reduces to the search for three one-dimensional functions: (the components of ), and , satisfying certain normalization conditions. We used splines to model the functions numerically -

AlphaEvolve was prompted to produce three sequences of real numbers in the interval which served as the spline interpolation points. Evaluation was done by computing an approximation of by means of quadratures and exact derivative computations. Here for a closed curve we passed to the natural parametrization by computing the arc-length and taking the inverse by interpolating samples . We used and as tools for automatic differentiation, quadratures, splines and one-dimensional interpolation. The prompting strategy for AlphaEvolve was based on our standard search approach where AlphaEvolve can access the scoring function multiple times and update its guesses multiple times before producing the three sequences.In most runs

AlphaEvolve was able to obtain the circle as a candidate curve in a few iterations (along with a constant function ) - this corresponds to the conjectured lower bound of for . AlphaEvolve did not obtain the ovals as an additional class of optimal curves.6.9 Sendov's conjecture and its variants

We tested

AlphaEvolve on a well known conjecture of Sendov, as well as some of its variants in the literature.Problem 20: Sendov's conjecture

For each , let be the smallest constant such that for any complex polynomial of degree with zeros in the unit disk and critical points ,

Sendov [89] conjectured that .

It is known that

with the upper bound found in [90]. For the lower bound, the example shows that , while the example shows the slightly weaker . The first example can be generalized to for and real ; it is conjectured in [91] that these are the only extremal examples.

Sendov's conjecture was first proved by Meir--Sharma [92] for , Brown [93] (), Borcea [94] and Brown [95] (), Brown-Xiang [96] () and Tao [97] for sufficiently large . However, it remains open for medium-sized .

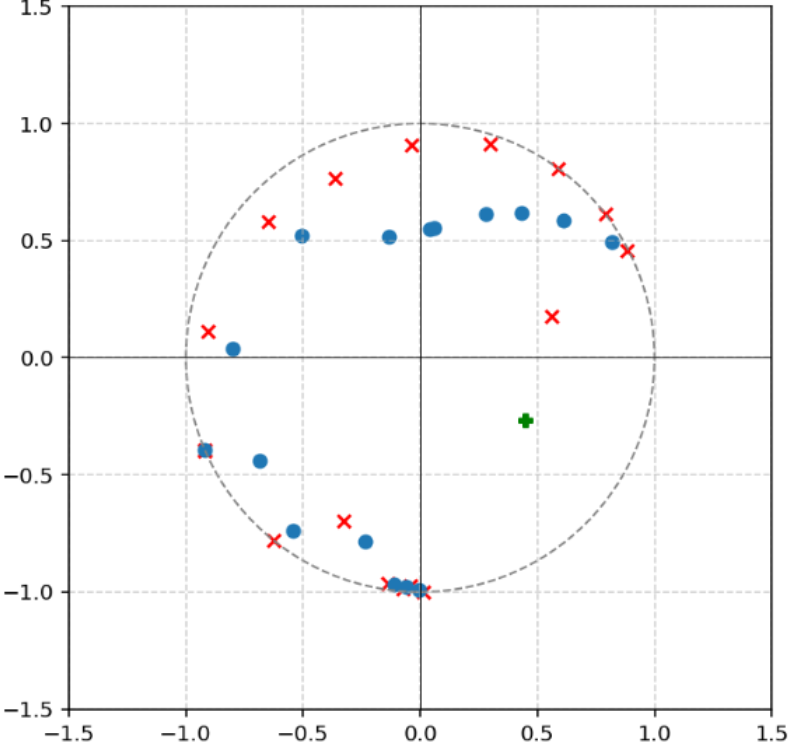

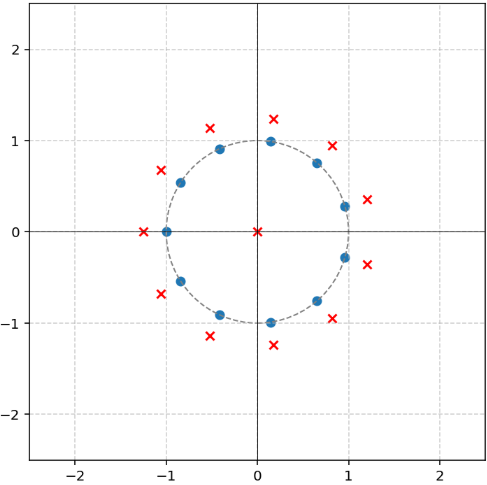

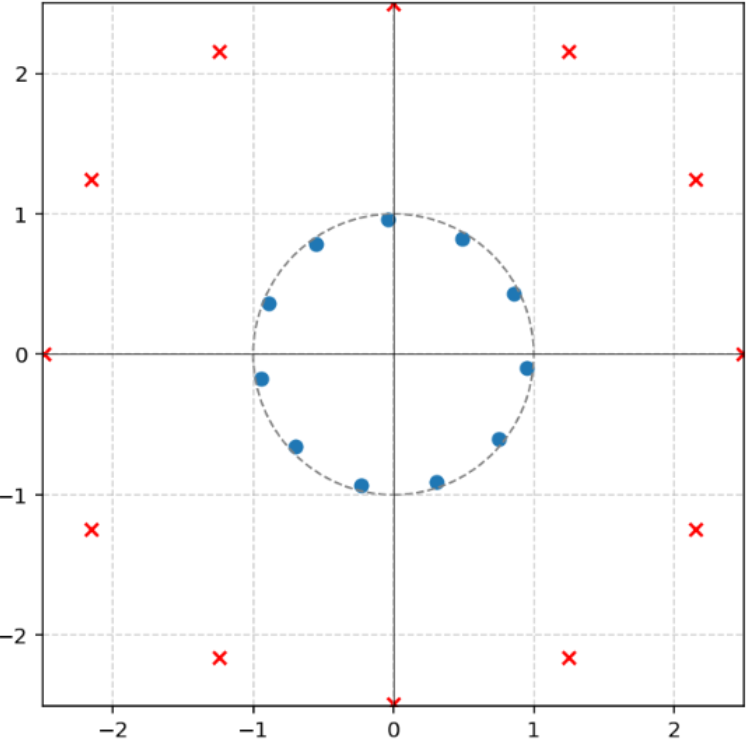

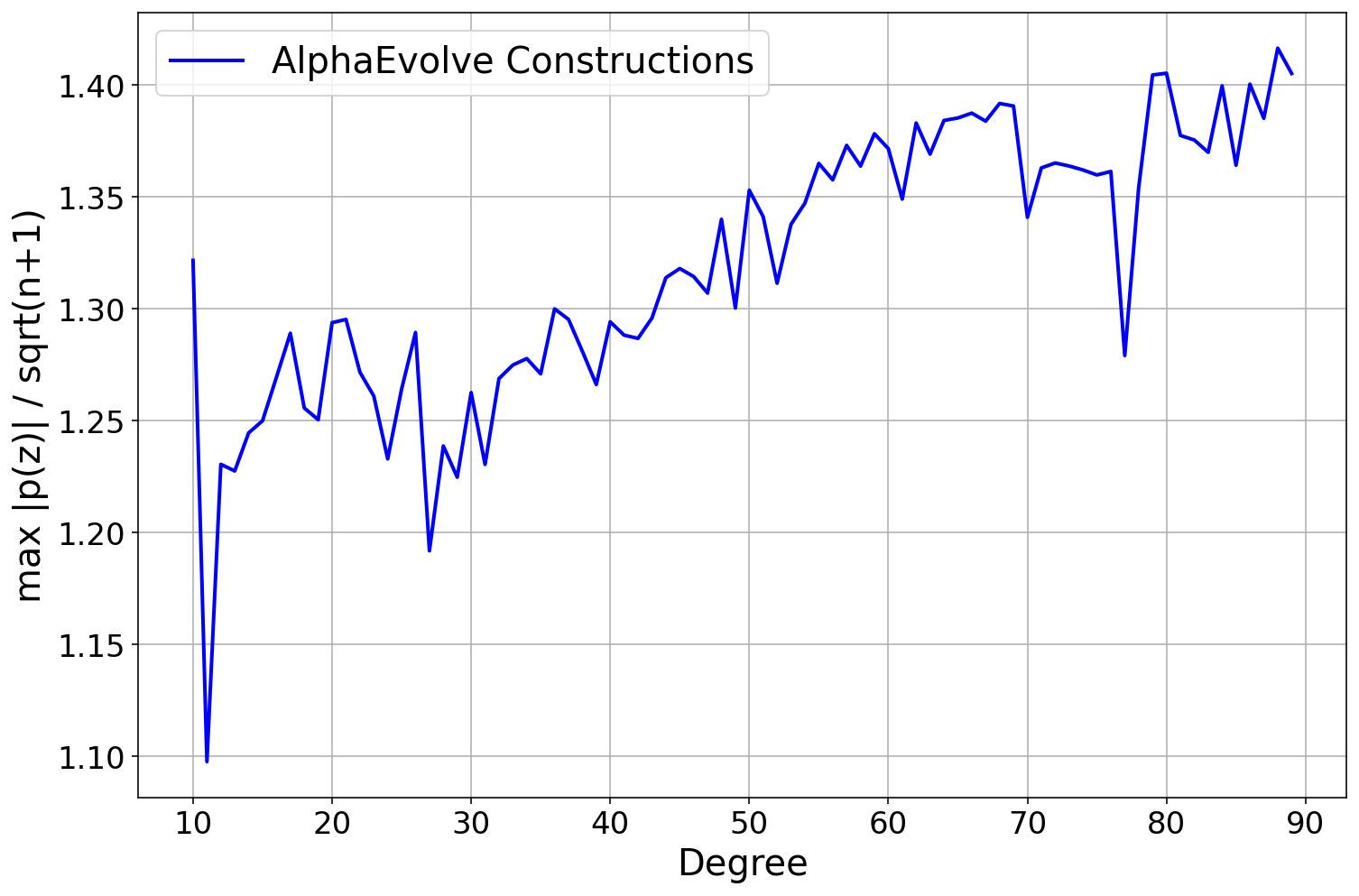

We tried to rediscover the example that gives the lower bound and aimed to investigate its uniqueness. To do so, we instructed

AlphaEvolve to choose over the set of all sets of roots . The score computation went as follows. First, if any of the roots were outside of the unit disk, we projected them onto the unit circle. Next, using the numpy.poly, numpy.polyder, and np.roots functions, we computed the roots of and returned the maximum over of the distance between and the . AlphaEvolve found the expected maximizers and near-maximizers such as , but did not discover any additional maximizers.Problem 21: Schmeisser's conjecture

. For each , let be the smallest constant such that for any complex polynomial of degree with zeros in the unit disk and critical points , and for any nonnegative weights satisfying , we have

It was conjectured in [98,99] that .

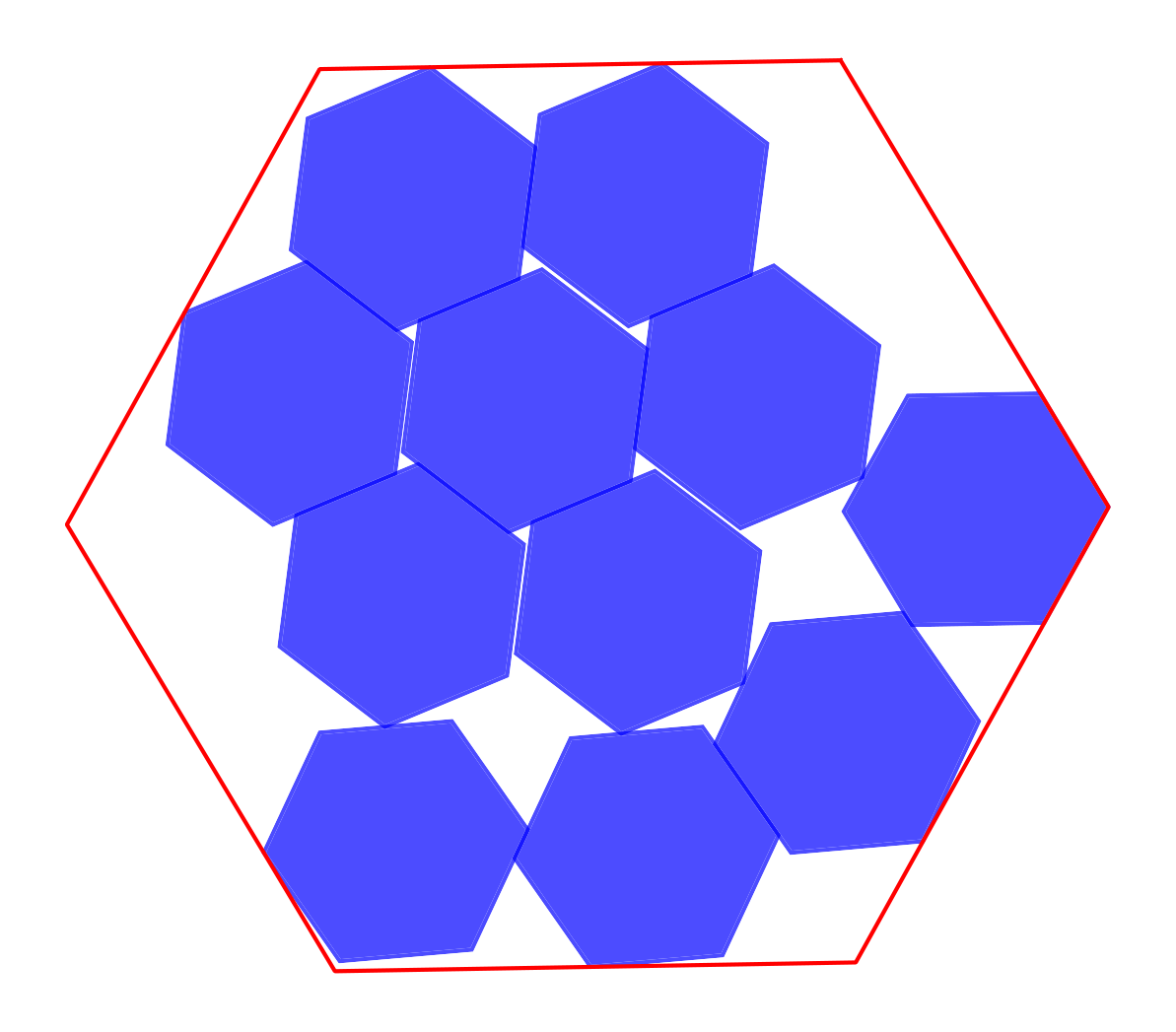

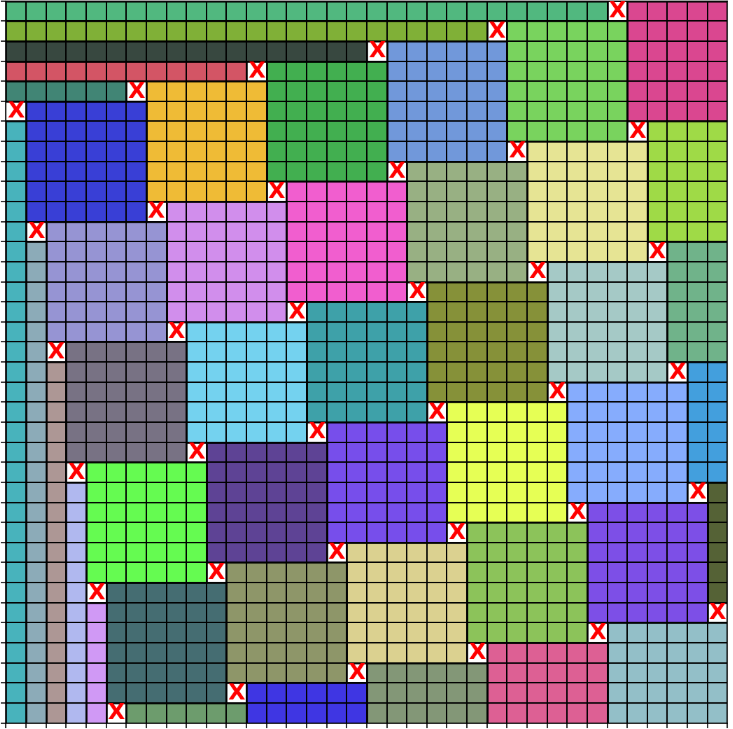

Clearly . This is stronger than Sendov's conjecture and we hoped to disprove it. As in the previous subsection, we instructed

AlphaEvolve to maximize over sets of roots. Given a set of roots, we deterministically picked many points on their convex hull (midpoints of line segments and points that divide line segments in the ratio 2:1), and computed their distances from the critical points. AlphaEvolve did not manage to find a counterexample to this conjecture. All the best constructions discovered by AlphaEvolve had all roots and critical points near the boundary of the circle. By forcing some of the roots to be far from the boundary of the disk one can get insights about what the "next best" constructions look like, see Figure 15.Problem 22: Borcea's conjecture

For any and , let be the smallest constant such that for any complex polynomial of degree with zeroes satisfying

and every zero of , there exists a critical point of with . What is ?

From Hölder's inequality, is non-increasing in and tends to in the limit . It was conjectured by Borcea3 ([100], Conjecture 1) that for all and . This version is stronger than Sendov's conjecture and therefore potentially easier to disprove. The cases are of particular interest; the cases were verified in [100].

In the notation of [100], the condition Equation 6 implies that , where , and the claim that a critical point lies within distance of any zero is the assertion that . Thus, the statement of Borcea's conjecture given here is equivalent to that in ([100], Conjecture 1) after normalizing the set of zeroes by a dilation and translation.

We focused our efforts on the case. Using a similar implementation to the earlier problems in this section,

AlphaEvolve proposed various and type constructions. We tried several ways to push AlphaEvolve away from polynomials of this form by giving it a penalty if its construction was similar to these known examples, but ultimately we did not find a counterexample to this conjecture.Problem 23: Smale's problem

For , let be the least constant such that for any polynomial of degree , and any with , there exists a critical point such that

Smale [101] established the bounds

with the lower bound coming from the example . Slight improvements to the upper bound were obtained in [102], [103], [104], [105]; for instance, for , the upper bound was obtained in [105]. In ([101], Problem 1E), Smale conjectured that the lower bound was sharp, thus .

We tested the ability of

AlphaEvolve to recover the lower bound on with a similar setup as in the previous problems. Given a set of roots, we evaluated the corresponding polynomial on points given by a 2D grid. AlphaEvolve matched the best known lower bound for by finding the optimizer, and also some other constructions with similar score (see Figure 16), but it did not manage to find a counterexample.Now we turn to a variant where the parameters one wishes to optimize range in a two-dimensional space.

Problem 24: de Bruin–Sharma

For , let be the set of pairs such that, whenever is a degree polynomial whose roots sum to zero, and are the critical points (roots of ), that

What is ?

The set is clearly closed and convex. In [106] it was observed that if all the roots are real (or more generally, lying on a line through the origin), then Equation 7 in fact becomes an identity for

They then conjectured that this point was in , a claim that was subsequently verified in [107].

From Cauchy--Schwarz one has the inequalities

and from simple expansion of the square we have

and so we also conclude that also contains the points

By convexity and monotonicity, we further conclude that contains the region above and to the right of the convex hull of these three points.

When initially running our experiments, we had the belief that this was in fact the complete description of the feasible set . We tasked