Scaling Embeddings Outperforms Scaling Experts in Language Models

Hong Liu, Jiaqi Zhang${}^{}$, Chao Wang, Xing Hu, Linkun Lyu, Jiaqi Sun, Xurui Yang, Bo Wang, Fengcun Li, Yulei Qian, Lingtong Si, Yerui Sun, Rumei Li, Peng Pei${}^{}$, Yuchen Xie, Xunliang Cai

Meituan LongCat Team

Correspondence: Corresponding authors: [email protected], [email protected]

Abstract

While Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures have become the standard for sparsity scaling in large language models, they increasingly face diminishing returns and system-level bottlenecks. In this work, we explore embedding scaling as a potent, orthogonal dimension for scaling sparsity. Through a comprehensive analysis and experiments, we identify specific regimes where embedding scaling achieves a superior Pareto frontier compared to expert scaling. We systematically characterize the critical architectural factors governing this efficacy—ranging from parameter budgeting to the interplay with model width and depth. Moreover, by integrating tailored system optimizations and speculative decoding, we effectively convert this sparsity into tangible inference speedups. Guided by these insights, we introduce LongCat-Flash-Lite, a 68.5B parameter model with $\sim$3B activated trained from scratch. Despite allocating over 30B parameters to embeddings, LongCat-Flash-Lite not only surpasses parameter-equivalent MoE baselines but also exhibits exceptional competitiveness against existing models of comparable scale, particularly in agentic and coding domains.

Hugging Face: https://huggingface.co/meituan-longcat/LongCat-Flash-Lite

![**Figure 1:** The architecture of a N-gram Embedding layer [1]. The embedding of each token is augmented by the N-gram Embedding branch.](https://ittowtnkqtyixxjxrhou.supabase.co/storage/v1/object/public/public-images/jdt4pe3w/NE-overview.png)

1. Introduction

The Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture has firmly established itself as the dominant paradigm for scaling Large Language Models (LLMs), enabling massive parameter counts while maintaining manageable computational costs [2]. By dynamically routing tokens to a subset of experts, models decouple parameter capacity from computational cost, allowing LLMs to scale to trillons of parameters while keeping modest inference latency. However, as the model size and sparsity level increase, the marginal gain in performance diminishes, eventually approaching an efficiency saturation point [3]. Furthermore, the practical expansion of experts is constrained by system-level bottlenecks, particularly the escalating communication overhead and memory bandwidth pressure in distributed training. This necessitates the exploration of alternative, orthogonal dimensions for scaling sparse parameters beyond the Feed-Forward Networks (FFNs).

In contrast to MoE, the embedding layer offers an overlooked, inherently sparse dimension with $O(1)$ lookup complexity. This allows for massive parameter expansion without routing overheads—effectively achieving parameter extension without computation explosion. Theoretical foundations for this dimension have been established by scaling laws with vocabulary [4], which posit that larger models necessitate proportionally larger vocabularies to maximize computation efficiency. To exploit this potential, diverse strategies have been proposed. One prominent direction is structural expansion, exemplified by Per-Layer Embedding (PLE) [5, 6, 7], which allocates independent embedding parameters to each layer to scale capacity. Another key direction is vocabulary expansion via n-grams to densify information per token. This concept traces back to lookup-table language models [39] in the RNN era and has recently been advanced in LLMs [8, 1, 9, 10]. These approaches collectively highlight the embedding layer as a fertile ground for scaling.

Despite the recent interest in expanding embedding parameters in LLMs, several key challenges remain underexplored. First, the comparative scaling efficiency between expert parameters and embedding parameters is not well understood, leaving the optimal allocation of capacity between these two sparse dimensions ambiguous. Second, the constraints of scaling embeddings are still not systematically characterized: it remains unclear how factors such as the total parameter budget, vocabulary size, initialization schemes, and the trade-offs between model width and depth jointly influence the effectiveness and stability of embedding scaling. Third, while some methods for scaling embeddings have been proposed, it is still unclear which scaling strategy is more effective and efficient under different regimes. Finally, scaling embeddings alters the input/output characteristics of the model during decoding, potentially impacting the overall I/O efficiency, yet its consequences for end-to-end inference performance remain insufficiently analyzed and optimized.

In this technical report, we present a study to address these challenges and establish a robust framework for embedding scaling. Our contributions are as follows:

- Comparison of Embedding Scaling vs. Expert Scaling: Through comprehensive scaling experiments across diverse scenarios, we identify specific regimes where embedding scaling achieves a superior Pareto frontier compared to increasing expert numbers, offering a high-efficiency alternative for model scaling.

- Impact Analysis of Architectural Factors: We establish the complete set of architectural factors determining embedding scaling efficacy, covering the integration timing, parameter budgeting, hash collisions, hyperparameter settings and initialization of embedding, together with the effects of model width and depth. Besides, we investigate different methods of scaling embedding and find that N-gram Embedding offers the most robust scalability.

- Inference Efficiency and System Optimization: We demonstrate that N-gram Embedding largely reduce I/O bottlenecks in MoE layers, particularly when paired with speculative decoding to maximize hardware utilization. Addressing the concomitant embedding overhead, we propose a specialized N-gram Cache and synchronized kernels, ensuring that the reduction in active parameters translates directly to lower latency and higher throughput.

Based on these findings, we introduce and open-source LongCat-Flash-Lite, a model trained from scratch with 68.5B total parameters and 2.9B $\sim$ 4.5B activated parameters depending on the context. Our evaluation demonstrates that LongCat-Flash-Lite not only surpasses a parameter-equivalent MoE baseline—validating the superior efficacy of allocating over 30B parameters to embeddings rather than experts—but also exhibits competitive performance against existing models of similar scale, particularly in agentic and coding tasks.

2. N-gram Embedding Layer

To scale the embedding parameters, we adopt the N-gram Embedding introduced in [8, 1, 9], which augments the representation of the embedding module by expanding a vocabulary-free n-gram embedding table. Specifically, for the $i$-th token $t_i$ in a sequence, the augmented embedding $e_i$ is calculated as follows

$ e_i = \frac{1}{N}\big(E_0(t_i) + \sum_{n=2}^N E_n(\mathcal{H}n(t{i-n+1}, ..., t_i))\big), \tag{1} $

where $t_{j} = 0$ if $j \leq 0$,

where $E_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{V_0 \times D}$ is the original base embedding table with hidden size $D$, $E_n \in \mathbb{R}^{V_n \times D}$ is the expanded embedding table, $N$ denotes the maximum n-gram order and $\mathcal{H}_n$ denotes the hash mapping function. We use the polynomial rolling hash funciton:

$ \mathcal{H}n(t{i-n+1}, ..., t_i) = (\sum_{j=0}^{n-1} t_{i-j} * V_0^j) % V_n. \tag{2} $

To further enhance the model's expressive ability and reduce hash collisions, [8, 1] decompose each n-gram embedding table into $K$ sub-tables with different vocabulary size. [1] further incorporate additional linear projection to map the outputs back to the original embedding space. The final version of N-gram Embedding (also referred to as Over-Encoding in [1]) is shown in Figure 1 and can be written as

$ e_i = \frac{1}{(N-1)K+1}\Big(E_0(t_i) + \sum_{n=2}^N \sum_{k=1}^K W_{n, k}E_{n, k}(\mathcal{H}{n, k}(t{i-n+1}, ..., t_i))\Big), \tag{3} $

where $E_{n, k} \in \mathbb{R}^{V_{n, k} \times D/((N-1)K)}$ is a sub-table and $W_{n, k} \in \mathbb{R}^{D \times D/((N-1)K)}$ is the linear projection matrix. By setting the hidden size of sub-tables to be inversely proportional to the number of sub-tables, this design ensures that the parameter count of N-gram Embedding remains invariant with respect to $N$ and $K$.

3. Comparative Analysis of Expert and Embedding Scaling

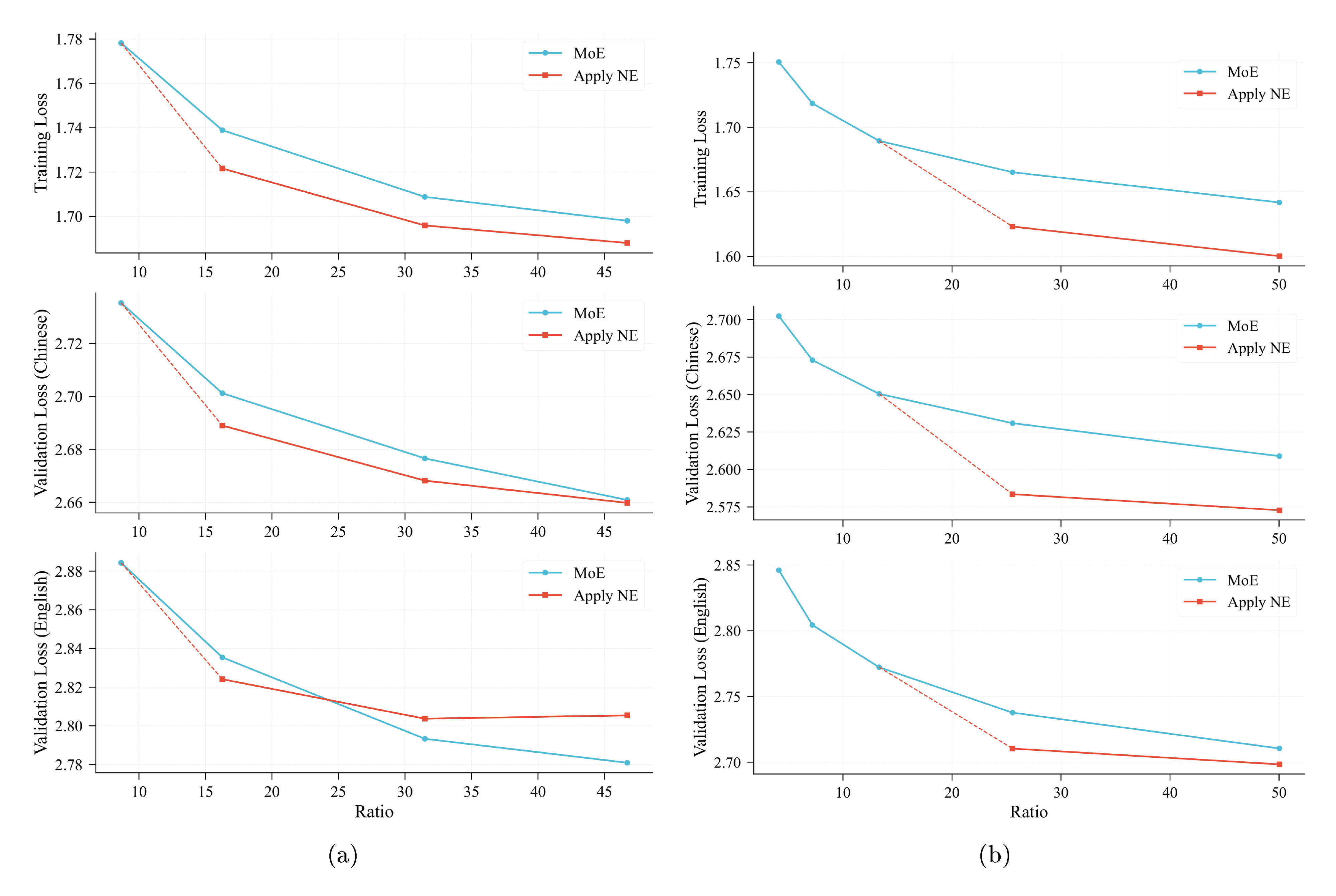

This section presents our empirical findings regarding the comparison between scaling embeddings and scaling experts.

Experiment Settings

We integrate N-gram Embedding into the Longcat-Flash architecture [11] and conduct scaling experiments via from-scratch pre-training across varying activated parameter budgets (280M, 790M, and 1.3B). To rigorously compare scaling strategies, we establish a framework that contrasts scaling via N-gram Embedding against scaling experts. Specifically, for N-gram Embedding scaling, we first train MoE models with varying base sparsity levels ranging from 35% to 98% and incrementally incorporate N-gram Embedding from specific sparsity levels. Crucially, at each sparsity level, the N-gram Embedding model is paired with a parameter-equivalent MoE baseline, which attains the same total parameter count by increasing the number of experts. All models are pre-trained on a corpus of 300B tokens. We evaluate model performance by monitoring training loss and validation loss on two meticulously constructed datasets, covering both Chinese and English.

3.1 Optimal Timing for N-gram Embedding Integration

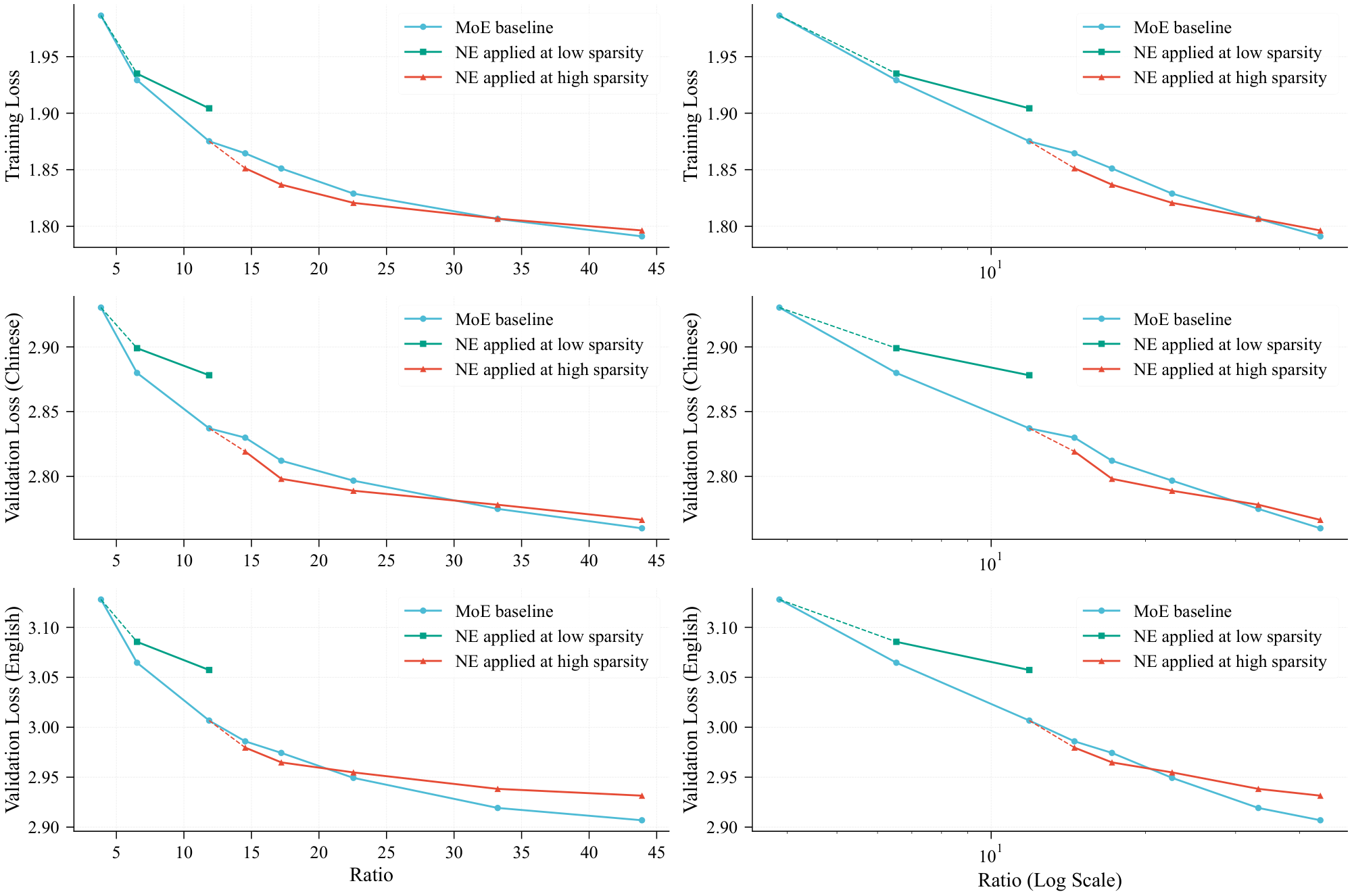

A pivotal finding is that the scaling dynamics of N-gram Embedding diverge markedly depending on the sparsity level of the base model. Figure 2 presents three distinct scaling trajectories[^1]: the standard MoE baseline (blue), N-gram Embedding applied to a base model with a low parameter ratio (green), and N-gram Embedding applied to a base model with a high parameter ratio (red).

[^1]: We utilize the ratio of total parameters to activated parameters on the x-axis as a proxy for sparsity.

The figure illustrates that the MoE scaling curve adheres to a strict log-linear relationship. This implies that in low-ratio regimes, a marginal increase in the number of experts yields a substantial reduction in loss. Conversely, at higher ratios, achieving an equivalent loss reduction necessitates a significantly larger increase in expert parameters. Consequently, when N-gram Embedding is introduced at low parameter ratios, its scaling advantage fails to surpass the gains obtained by simply increasing the number of experts. In contrast, at high sparsity levels, the benefits of N-gram Embedding become significantly more pronounced. This observation leads to the following design principle regarding the incorporation of N-gram Embedding.

Summary: N-gram Embedding should be introduced when the number of experts exceeds its "sweet spot".

This result indicates that embedding scaling could be a promising scaling dimension orthogonal to expert scaling.

3.2 Integration Strategy

3.2.1 Parameter Budgeting for N-gram Embeddings

A closer inspection of Figure 2 reveals a distinct intersection between the blue and red curves: as the parameter ratio increases, the performance advantage of N-gram Embedding gradually diminishes and is eventually surpassed by the MoE baseline. This indicates that when a model allocates an excessive proportion of its parameter budget to N-gram Embedding, its performance becomes inferior to that of parameter-equivalent MoE baselines. This observation aligns with conclusions drawn in the concurrent work Engram [10], which posits that the loss follows a U-shaped scaling curve as a function of the N-gram Embedding proportion. In Figure 2, the intersection point lies slightly above a ratio of 20. At this juncture, N-gram Embedding parameters constitute approximately 50% of the total parameter count (given that the base MoE model maintains a ratio of 12). Consequently, we derive a second principle from this phenomenon:

Summary: Allocate no more than 50% of the total parameter budget to N-gram Embedding.

3.2.2 Mitigating Hash Collisions via Vocabulary Sizing

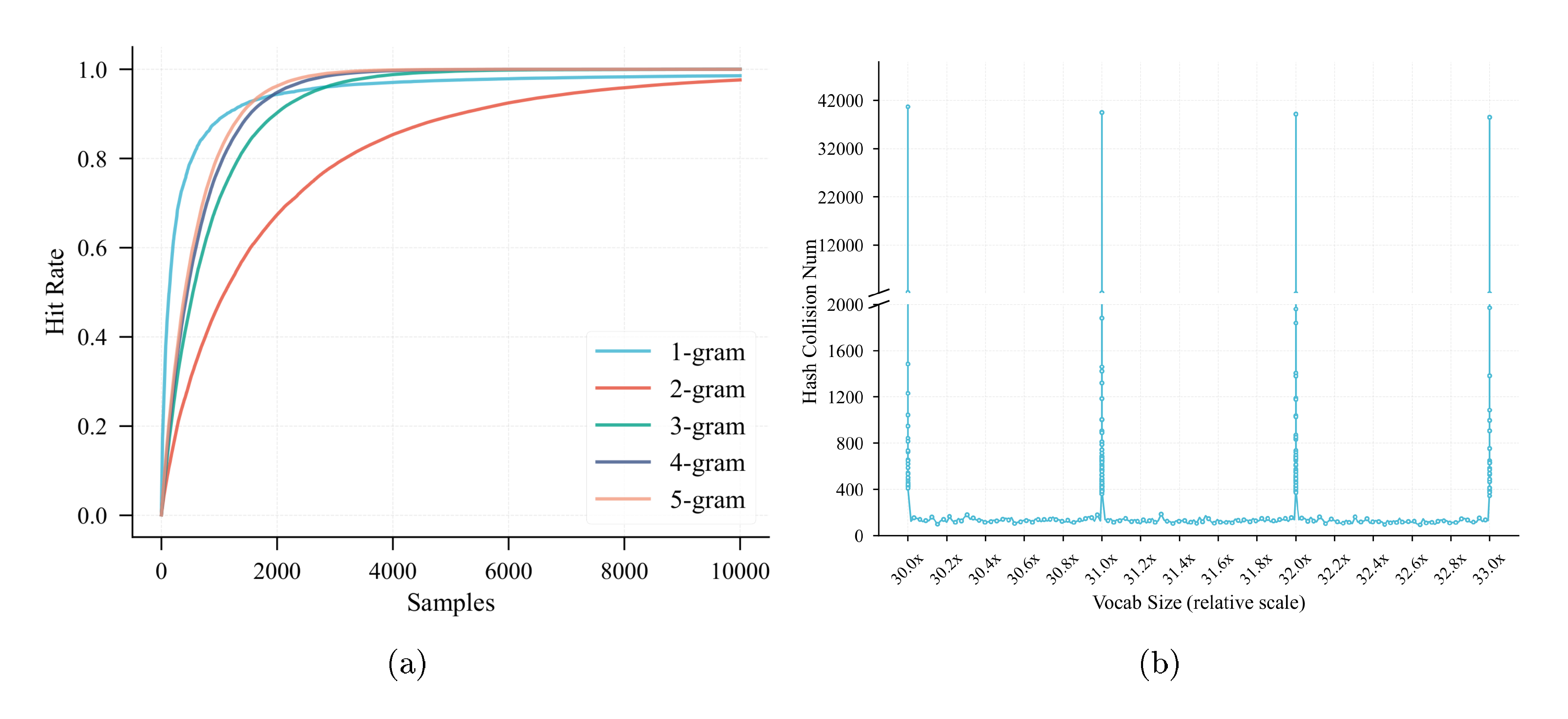

In the context of N-gram Embedding, hash collisions force a single embedding vector to superimpose the semantics of multiple distinct n-grams. This collision-induced ambiguity impedes learning efficiency and consequently degrades model performance. We identify that selecting an appropriate vocabulary size is critical to mitigating high collision rates. During training, we observed that N-gram Embedding exhibits anomalously high hash collision rates at specific vocabulary sizes, particularly for 2-gram hashing. To investigate the underlying mechanics, we conduct a dual analysis focusing on: (1) Vocabulary Hit Rate, defined as the proportion of vocabulary entries activated at least once by the pre-training corpus; and (2) Hash Collisions, which quantifies the loss of unique token representation due to modulo-based indexing.

For the hit rate analysis, we use an n-gram vocabulary size set to $30\times$ the base vocabulary (128k). For the collision analysis, we sample a range of vocabulary sizes between $30\times$ and $33\times$ the base vocabulary size, computing n-gram collision counts over 100 training sequences for each configuration. The results are detailed in Figure 3.

Figure 3a illustrates that 2-gram hashing exhibits a gradual increase in hit rate, whereas higher-order n-gram hashing rapidly converges toward a hit rate of 1.0. Independent of the hit rate trends, we observe in Figure 3b that 2-gram hashing collision numbers display a strong, non-linear correlation with vocabulary size. A salient pattern emerges: collision counts spike noticeably when the vocabulary size approaches an integer multiple of the base vocabulary size. This phenomenon persists regardless of whether the n-gram vocabulary size is a prime number. Synthesizing these observations, Figure 3b motivates an additional design principle for configuring N-gram Embedding:

Summary: The vocabulary size of N-gram Embedding should significantly deviates from integer multiples of the base vocabulary size to prevent Hash collisions.

3.2.3 Sensitivity Analysis of Hyperparameters

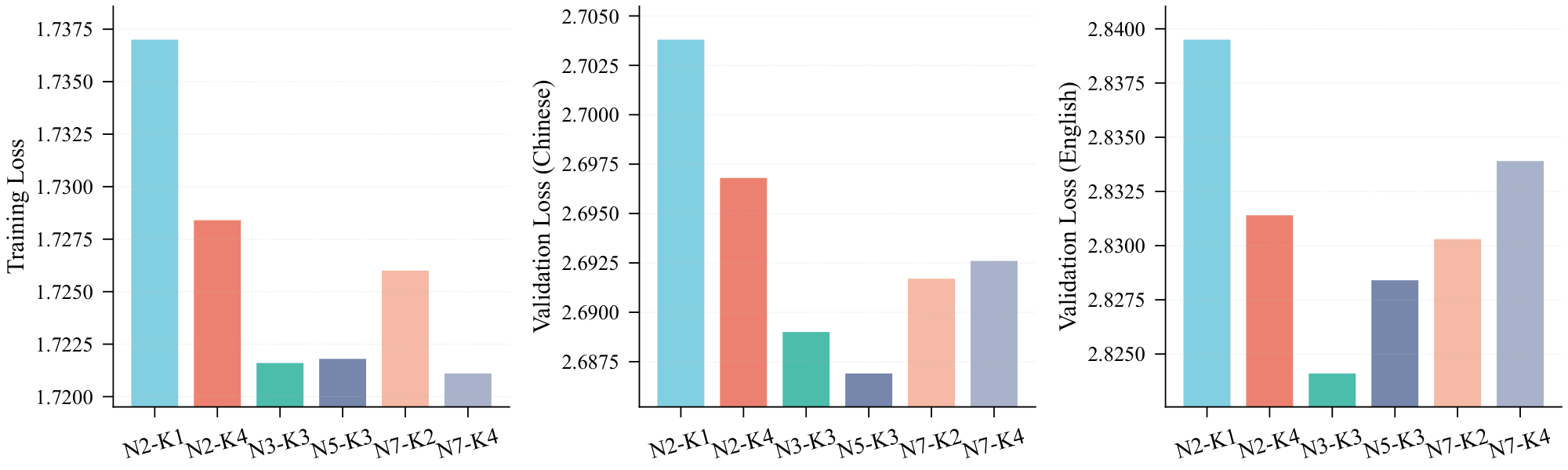

We now examine the sensitivity of model performance to the internal configurations of N-gram Embedding, namely the n-gram order $N$ and the number of sub-tables $K$.

Regarding the n-gram order $N$ defined in Section 2, increasing $N$ enables N-gram Embedding to capture richer contextual semantics, theoretically yielding embedding vectors with enhanced representational capacity. However, this also creates an extremely sparse distribution over the n-gram vocabulary, as high-order n-grams appear infrequently. This sparsity significantly exacerbates the challenge of learning effective embeddings.

Regarding the number of sub-tables $K$, this parameter governs the number of distinct hash functions applied to each n-gram, thereby substantially mitigating the probability of hash collisions. Nevertheless, empirical evidence suggests that increasing $K$ beyond a certain threshold yields diminishing returns.

Utilizing the 790M activated-parameter model (corresponding to the initial data point on the red curve in Figure 6a), we conduct ablation studies across various combinations of $N$ and $K$ [^2]. The results are summarized in Figure 4. It is evident that when both $N$ and $K$ are set to their minimal values ($N = 2$ and $K = 1$), the model exhibits notably inferior performance. Conversely, for $N \ge 3$ and $K \ge 2$, the performance variance across different configurations becomes relatively small, indicating that the model is robust to hyperparameter selection within this regime. Empirically, we observe that setting $N$ in the range of 3 to 5 consistently yields near-optimal performance.

[^2]: For large $N$, numerical overflow during hash computation can be circumvented by applying the modulus operation prior to exponentiation.

3.2.4 Embedding Amplification for Effective Training

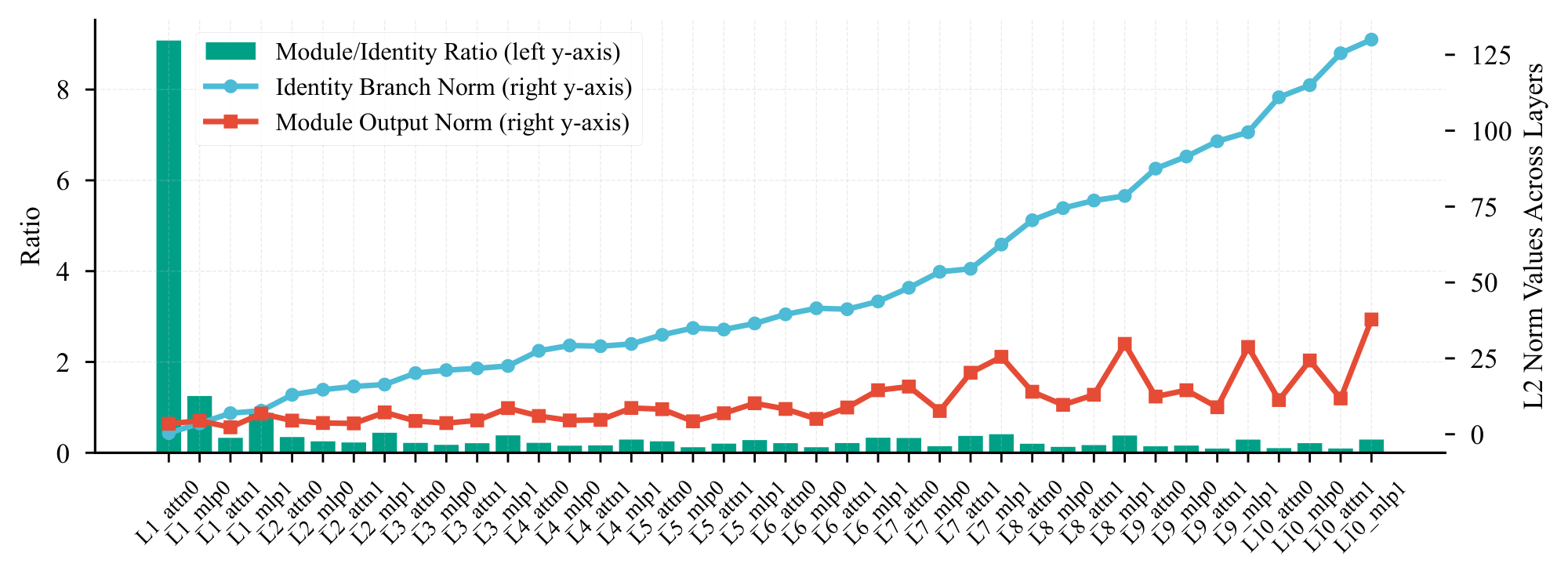

In our preliminary experiments, we observed that suboptimal initialization of the embedding module can severely impede the efficacy of N-gram Embedding, preventing it from realizing its full potential. To validate this hypothesis, we revisited an early vanilla experiment configured as per Figure 2, but without any specific adjustments to the embedding module. After pre-training on 300B tokens, we compute the L2 norms of each module’s output and its corresponding residual branch (identity path) across all layers, plotting the norms and their ratios in Figure 5.

Figure 5 exposes a critical disparity: the L2 norm of the first attention module's output is an order of magnitude larger (approximately $10\times$) than that of the corresponding identity branch, which essentially represents the output of the embedding module. This indicates that upon summation, the attention output dominates the residual stream, effectively "drowning out" the embedding signal. Although standard initialization of sub-tables and projection matrices in N-gram Embedding ensures that initial output norms match the baseline, this signal suppression phenomenon exacerbates significantly once training progress, leading to substantial performance degradation in N-gram Embedding models.

To mitigate this issue, we explore two strategies:

- Scaling Factor: Introducing a scaling factor (typically $\sqrt{D}$) to the embedding output to ensure a sufficient contribution to the forward pass.

- Normalization: Applying LayerNorm to the embedding output prior to merging with the residual branch. This similarly amplifies the embedding contribution, as LayerNorm enforces unit variance during the early stages of training.

Both techniques were originally proposed in [12] with the primary objective of increasing residual branch variance to bound backward gradients and stabilize training. In our context, while we observed no significant impact on training stability, these methods—collectively termed Embedding Amplification—substantially enhance the performance of N-gram Embedding. In our experiments, applying Embedding Amplification yields superior performance compared to the vanilla baseline, with a consistent reduction of 0.02 in both the training loss and the two validation losses.

3.3 Scaling Properties across Model Width and Depth

3.3.1 Enhanced Advantage in Wider Models

This section investigates how the efficacy of N-gram embedding scaling evolves with increasing model width.

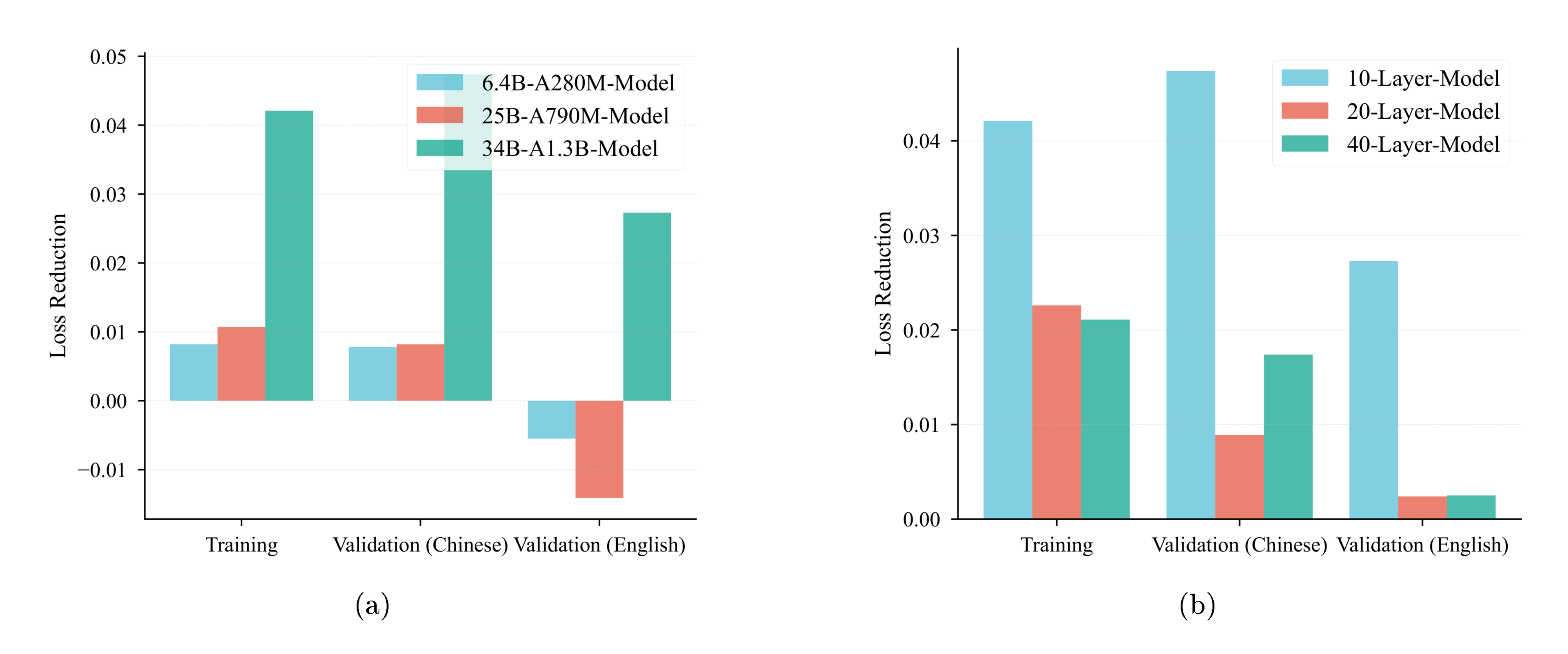

We conduct a series of scaling experiments at two larger activation scales (790M and 1.3B parameters), with model depth held constant (10 shortcut layers) while only the width (hidden size and module dimensions) varies. Figure 6 presents the resulting scaling curves. Our analysis reveals two key trends:

- When incorporated at an appropriate ratio, N-gram Embedding consistently yields a lower loss compared to a parameter-equivalent MoE baseline. This advantage gradually diminishes as the proportion of N-gram Embedding parameters increases, mirroring the behavior observed in Figure 2.

- Crucially, the intersection point between the N-gram Embedding curve and the MoE curve systematically shifts towards higher total-to-activated parameter ratios as the model width (activation size) increases. Specifically, for a 280M activation size, N-gram Embedding consistently underperforms its MoE counterpart once the ratio exceeds 30. At 790M, N-gram Embedding only underperforms on the English validation set at this ratio, while maintaining an advantage on all other metrics. Notably, at a 1.3B activation size, N-gram Embedding retains a clear advantage even at ratios as high as 50.

These findings demonstrate that wider models allow for a significantly expanded window of opportunity to leverage N-gram Embedding effectively. Consequently, Figure 6 leads to the following conclusion: for a fixed number of layers,

Summary: Increasing model width confers a greater advantage to N-gram Embedding.

3.3.2 Diminishing Returns in Deeper Models

We now investigate the impact of model depth on the efficacy of N-gram Embedding scaling. For pre-normalization architectures, the contribution of N-gram Embedding through the identity connection (residual branch) inherently diminishes as network depth increases, as the signal propagating through skip connections carries less direct information from earlier layers (also shown in Figure 5).

To probe this hypothesis, we conducted scaling experiments using deeper architectures, building upon our 1.3B activated parameter configuration. Specifically, we trained models with 20 and 40 layers while meticulously maintaining a consistent relative proportion of N-gram Embedding parameters (50% of the total parameters) across all tested depths.

Figure 7b presents a clear comparison of the performance gap between N-gram Embedding and the MoE baseline across these varying depths. A striking observation emerges: as model depth surpasses 20 layers, the performance advantage of N-gram Embedding over the baseline experiences a pronounced contraction. This trend stands in contrast to the effect of increasing model width, as illustrated in Figure 7a, where the performance gap demonstrably widens.

Summary: Increasing model depth diminishes the relative advantage of N-gram Embedding.

Note that the majority of current practical language models typically operate below 40 shortcut layers (equivalent to 80 conventional layers). Given our finding that increased width consistently amplifies N-gram Embedding's advantage, and its robust performance even at 40 layers, scaling n-gram embeddings up within these common architectural depths is likely to yield even greater performance gains.

4. Efficient Inference

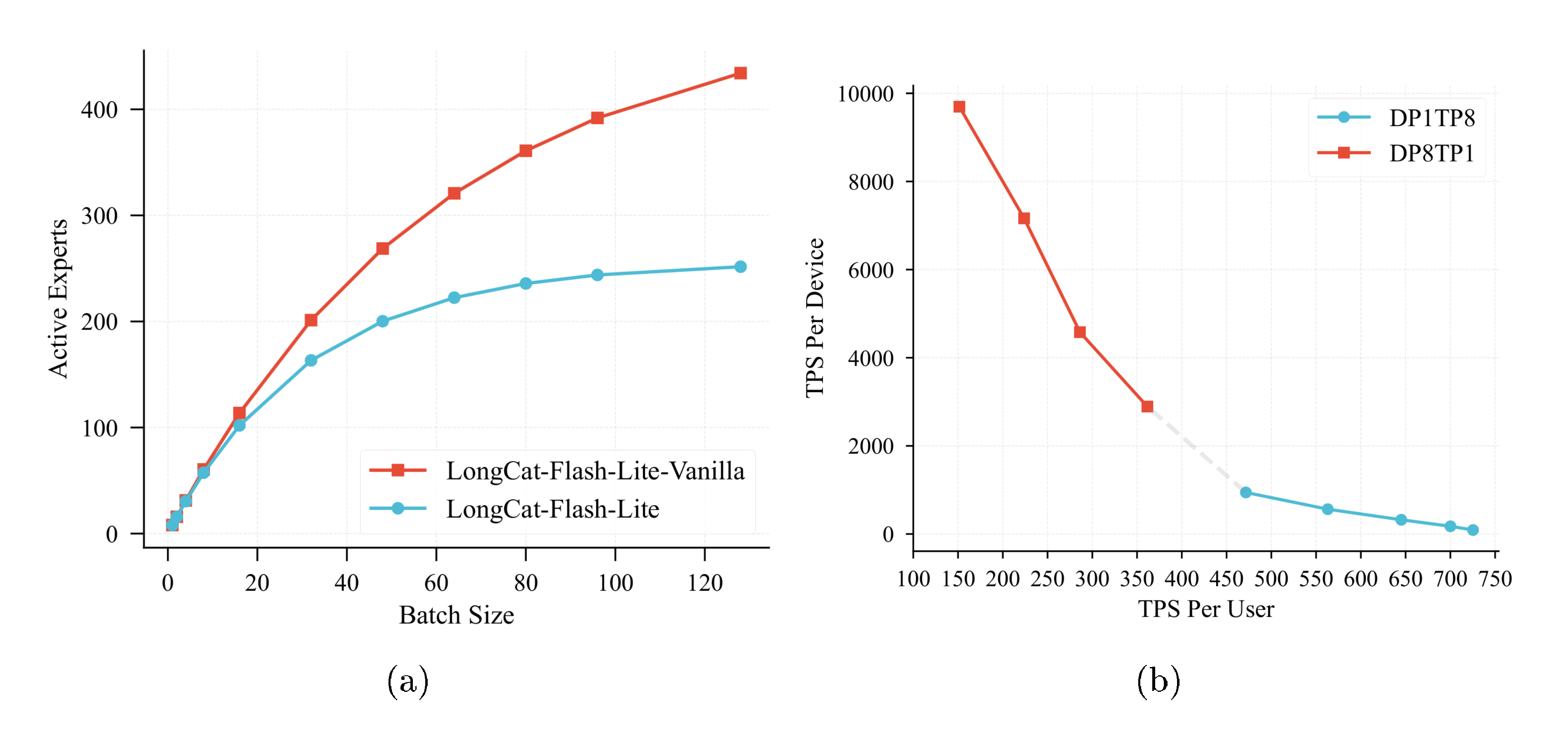

4.1 Reduction of MoE Activation Parameters

The N-gram Embedding mechanism effectively redistributes parameters from the MoE layers to the embedding space. This architectural transformation maintains the total model parameters while reducing the number of activated parameters within MoE layers—particularly advantageous in memory I/O-bound decoding scenarios with large token counts. Moreover, the increased size of the embedding layer does not penalize latency, as the computational cost of embedding lookups scales with the number of input tokens rather than the total number of embedding parameters.

To fully capitalize on the efficiency gains from reduced active parameters, it is crucial to maximize hardware utilization through a large batch size (as shown in Figure 8a). This requirement creates a natural synergy with speculative decoding. Multi-step speculative decoding effectively expands the "effective batch size", thereby converting the theoretical advantage of parameter sparsity into tangible inference speedups.

4.2 Optimized Embedding Lookup

Although reallocating parameters from experts to N-gram Embedding effectively reduces memory I/O for MoE layers, it introduces additional overhead in terms of I/O, computation, and communication compared to a standard embedding layer. Minimizing the latency and resource consumption of N-gram Embedding is therefore critical for overall system efficiency. Furthermore, the dynamic and complex scheduling mechanisms inherent in modern inference frameworks make it difficult to pre-determine the exact token sequences for the forward pass, which complicates the optimization of N-gram embedding lookups.

To address these challenges, we introduce the N-gram Cache, a specialized caching mechanism inspired by the design principles of the KV cache. We implement custom CUDA kernels to manage N-gram IDs directly on the device, facilitating low-overhead synchronization with the intricate scheduling logic of various inference optimization techniques. This design significantly enhances the computational efficiency of N-gram embeddings.

In speculative decoding scenarios, where the draft model typically operates with fewer layers and substantially lower latency, the overhead of N-gram Embedding becomes relatively more pronounced. To mitigate this, we propose two complementary optimization strategies: (1) employing a conventional embedding layer for the draft model to bypass the more computationally expensive n-gram lookup; and (2) caching n-gram embeddings during the drafting phase to eliminate redundant computations during the subsequent verification step. These optimizations collectively reduce latency and improve throughput in speculative inference settings.

4.3 Rethinking N-gram Embedding Optimization: The Role of Speculative Decoding

Beyond hardware efficiency, we posit that the N-gram Embedding structure inherently encodes rich local context and token co-occurrence information, offering unexplored synergies with speculative decoding. We identify two promising directions where the semantic richness of N-gram Embedding could potentially be leveraged to further accelerate inference.

N-gram Embedding based drafting: Since the N-gram Embedding aggregates information from the preceding N-1 tokens, it implicitly captures short-range dependencies. We are currently exploring architectures to repurpose the N-gram embedding as an ultra-fast draft model. While a primary candidate involves attaching a lightweight linear projection directly to the N-gram Embedding outputs, we are investigating a broader design space to fully exploit the captured local context for efficient token prediction.

Early rejection: The N-gram Embedding representation could also serve as a semantic consistency check (or confidence estimator) for tokens generated by external draft models. Draft tokens that result in low-probability match under N-gram Embedding might be "early-rejected" before entering the expensive verification phase of the target model. Theoretically, this pruning strategy would reduce the workload of the verification step, offering a pathway to further optimize end-to-end latency.

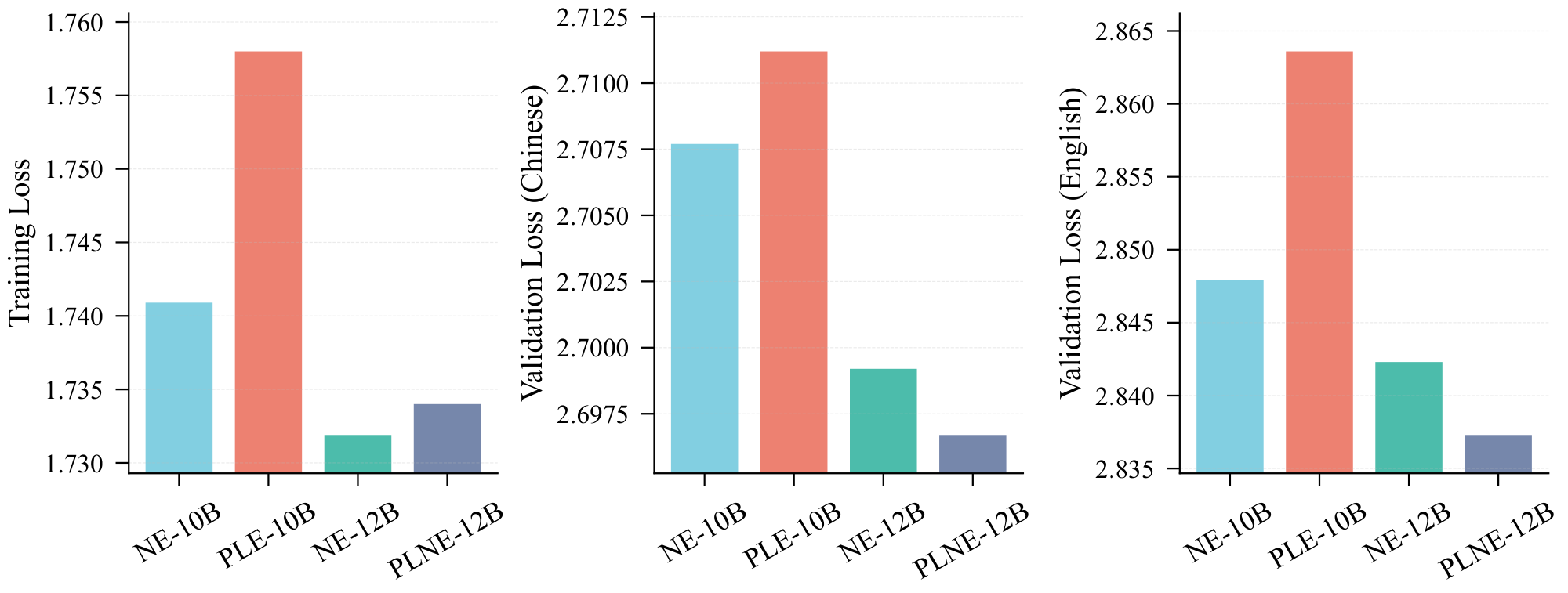

5. Integration with Per-Layer Embedding

As mentioned in Section 1, Per-Layer Embedding (PLE) is another way to scale parameters by allocating embedding parameters across layers. This section provides a direct comparison between N-gram Embedding and PLE, and introduces an attempt to integrate both approaches.

5.1 Per-Layer Embedding

PLE is applied in [13] and further studied in [6]. PLE directly substitutes the output of up-projection matrix in the SwiGLU module with the embedding output, which is the most efficient method for injecting embedding information in our experiments. Let $x^{(l)}_i$ be the $i$-th input vector of the FFN module in layer $l$, the FFN output with PLE can be formalized as follows

$ \text{FFN}^{(l)}(x_i) = W_d^{(l)}(\text{SiLU}(W^{(l)}_gx^{(l)}_i) \odot E_0^{(l)}(t_i)) \tag{4} $

where $W_d^{(l)}$ and $W^{(l)}_g$ denote the down-projection and gate-projection matrices of layer $l$ respectively, and $E_0^{(l)}$ is the embedding table of layer $l$, with identical shape to the base embedding table in Eq. 1.

5.2 Per-Layer N-gram Embedding

Building upon PLE, we propose Per-Layer N-gram Embedding (PLNE), a novel extension that replaces the base embedding outputs with N-gram Embedding outputs at each layer, thereby enabling more flexible and targeted parameter scaling within the MoE framework. PLNE can be written as

$ \text{FFN}^{(l)}(x_i) = W_d^{(l)}(\text{SiLU}(W^{(l)}_gx^{(l)}_i) \odot e^{(l)}_i) \tag{5} $

where $e^{(l)}_i$ is computed according to Eq. 3, with layer-specific embedding table and projection matrix.

5.3 Empirical Comparison

For both PLE and PLNE, embedding information is injected exclusively into the MLP within the dense sub-layer of each shortcut layer. Since each PLNE layer incorporates an n-gram vocabulary in addition to the base vocabulary, it introduces a larger number of parameters per layer compared to PLE. To avoid confounding factors related to layer positioning, we do not directly compare between PLE and PLNE under equivalent total parameter counts. Instead, we evaluate PLE and PLNE against their respective parameter-equivalent N-gram Embedding (NE) baselines, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9 reveals that PLE underperforms relative to N-gram Embedding, whereas PLNE yields marginal improvements over NE. We attribute the former to the superior learning efficiency of N-gram Embedding compared to standard embeddings. Consequently, we focused our scaling analysis on PLNE. However, in subsequent experiments involving increased model width or depth, PLNE failed to exhibit a consistent advantage, performing on par with NE in most scenarios. Given that PLNE inherently increases activated parameters (due to the addition of a substantial projection matrix in each layer), we opted not to adopt PLNE for our larger-scale experiments. Nonetheless, this approach merits further investigation—specifically regarding the optimal allocation of embedding parameters across layers, such as determining whether to concentrate them in a few specific layers or distribute them uniformly throughout the network.

6. LongCat-Flash-Lite

Leveraging the insights from our previous analysis, we introduce LongCat-Flash-Lite, a model trained from scratch with integrated N-gram Embedding. LongCat-Flash-Lite undergoes a complete pipeline of pre-training, mid-training, and supervised finetuning, and demonstrates highly competitive performance for its scale.

6.1 Model Information

Architecture

LongCat-Flash-Lite adopts the same architecture as Longcat-Flash [11], with a total of 14 shortcut layers. It has 68.5 billion total parameters and dynamically activates between 2.9B and 4.5B parameters per token due to the zero-experts. In each shortcut layer, the MoE module consists of 256 FFN experts and 128 zero-experts, and each token selects 12 experts. For embedding module, LongCat-Flash-Lite includes 31.4B N-gram Embedding parameters, accounting for 46% of the total.

Training Data

LongCat-Flash-Lite follows the same data recipe with LongCat-Flash-Chat [11]. It is first pre-trained on 11T tokens with a sequence length of 8k, followed by 1.5T tokens of mid-training during which the sequence length is extended to 128k, and is finally trained on SFT data. To support extended context, we implement YARN [14] during the 32k sequence length training stage, enabling LongCat-Flash-Lite to handle sequences up to 256k tokens.

Baseline without N-gram Embedding

We train an MoE baseline with exactly the same parameters as LongCat-Flash-Lite (referred to as LongCat-Flash-Lite-Vanilla) by converting all N-gram Embedding parameters into additional experts. Both models undergo identical training strategy and data recipe.

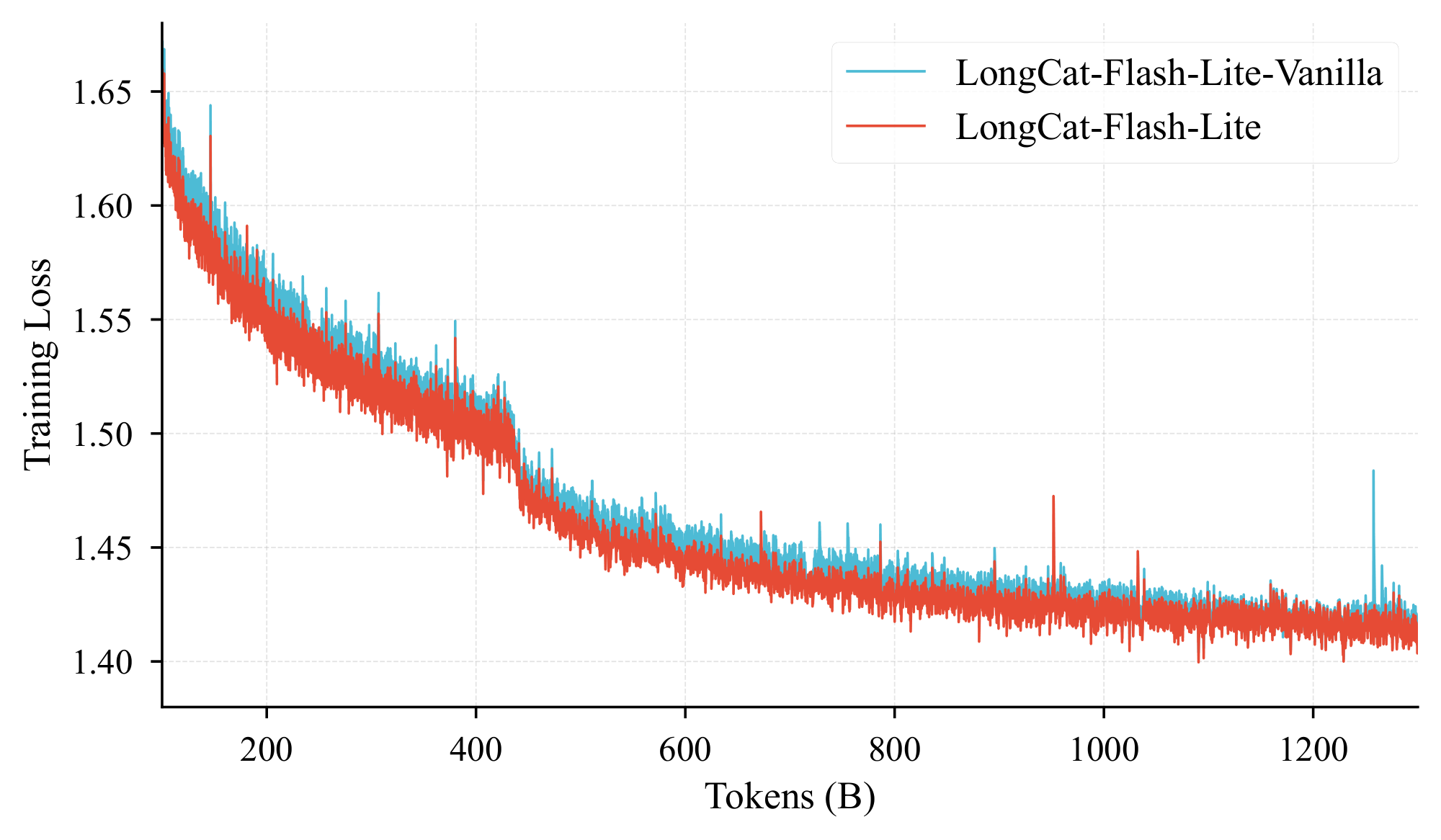

6.2 Base Model Evaluation

Throughout training, LongCat-Flash-Lite consistently achieves lower training loss compared to LongCat-Flash-Lite-Vanilla, as illustrated in Figure 10. To assess downstream performance, we evaluate both models on benchmarks spanning three core capability domains:

- General Tasks: MMLU [15], MMLU-Pro [16], C-Eval [17], and CMMLU [18].

- Reasoning Tasks: BBH [19], GPQA [20], DROP [21] and GSM8K [22].

- Coding Tasks: HumanEval+ [23], MultiPL-E [24], and BigCodeBench [25].

\begin{tabular}{ll|c|c}

\toprule

& BenchMark & [email protected] & [email protected] \\

\midrule

\multirow{4}{*}{General} & MMLU & \textbf{64.81} & 64.01 \\

& MMLU-pro & 34.43 & \textbf{35.89} \\

& CEval & 64.09 & \textbf{67.21} \\

& CMMLU & 67.08 & \textbf{69.55} \\

\midrule

\multirow{4}{*}{Reasoning} & BBH & 38.54 & \textbf{43.67} \\

& GPQA & 25.37 & \textbf{29.66} \\

& DROP & 47.92 & \textbf{52.43} \\

& GSM8K & 50.00 & \textbf{50.50} \\

\midrule

\multirow{3}{*}{Coding}

& HumanEval+ & 28.66 & \textbf{31.10} \\

& MultiPL-E & \textbf{30.20} & 30.03 \\

& BigCodeBench & 33.42 & \textbf{36.05} \\

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}

As detailed in Table 1, LongCat-Flash-Lite demonstrates substantial performance improvements over LongCat-Flash-Lite-Vanilla across the majority of benchmarks in all three domains. These findings validate our earlier analysis: when sparsity reaches sufficient levels, strategically scaling total parameters through N-gram Embedding —while maintaining an optimal proportion of embedding parameters—consistently outperforms approaches that merely increase expert numbers.

6.3 Chat Model Evaluation

The evaluation of the chat model covers several core capabilities: agentic tool use tasks, agentic coding tasks, general domain tasks and mathematical reasoning tasks. The benchmarks used for assessment include:

- Agentic Tool Use Tasks: $\tau^2$ Bench [26], Vita Bench [27]. For $\tau^2$-Bench, we use a revised version^3 to perform our evaluation because the original version contains noisy data.

- Agentic Coding Tasks: SWE-Bench [28], TerminalBench [29], SWE-Bench Multiligual [30], and PRDBench [31].

- General Domain Tasks: GPQA-Diamond [32], MMLU [15], MMLU-Pro [16], C-Eval [17], and CMMLU [18].

- Mathematical Reasoning Tasks: MATH500 [33], AIME24 [34], AIME25 [35].

:::

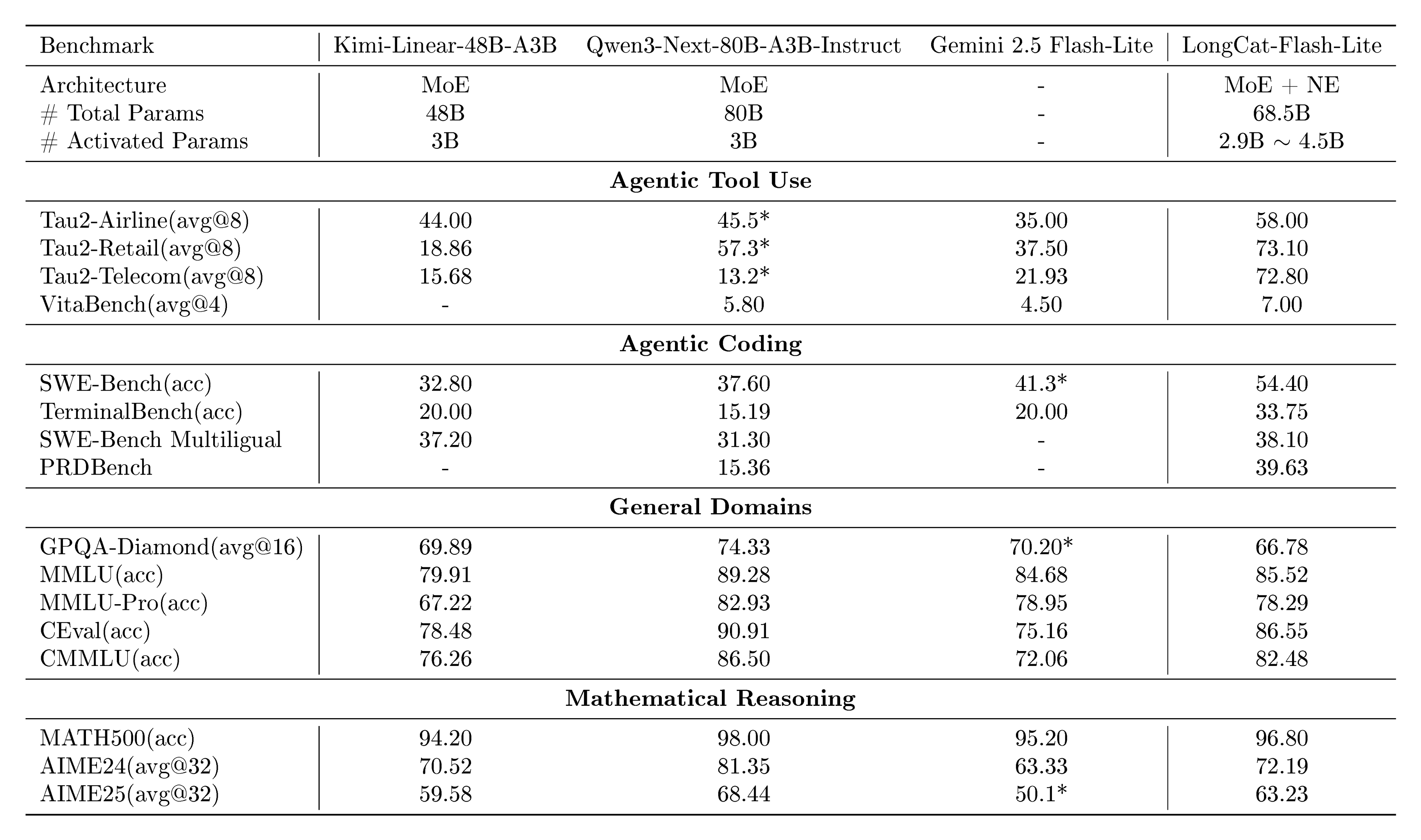

Table 2: Comparison between LongCat-Flash-Lite and other models. Values marked with * are sourced from public reports.

:::

Table 2 presents the comprehensive evaluation results of LongCat-Flash-Lite across various benchmark categories, along with comparisons with Qwen3-Next-80B-A3B-Instruct, Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite[^4], and Kimi-Linear-48B-A3B. LongCat-Flash-Lite demonstrates exceptional parameter efficiency and competitive performance across core capability dimensions.

[^4]: Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite Preview 09-2025

Agentic Tool Use. LongCat-Flash-Lite excels in agentic tool use tasks, establishing a clear lead over all comparison models. In the $\tau^2$-Bench benchmark, it achieves the highest scores across all three sub-scenarios: Telecom (72.8), Retail (73.1), and Airline (58.0). Notably, in the Telecom scenario, its score significantly outperforms Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite and Kimi-Linear-48B-A3B. This highlights its superior ability to handle complex dependencies on tools and domain-specific task execution. In VitaBench, it achieves a score of 7.00, outperforming Qwen3-Next-80B-A3B-Instruct (5.80), and Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite (4.50). This leading score underscores LongCat-Flash-Lite's superior ability to handle complex, real-world task workflows via tool integration in practical business scenarios.

Agentic Coding. In coding-related tasks, LongCat-Flash-Lite demonstrates remarkable practical problem-solving capabilities. In SWE-Bench, it achieves an accuracy of 54.4, outperforming all baselines—surpassing Qwen3-Next-80B-A3B-Instruct (37.6), Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite (41.3), and Kimi-Linear-48B-A3B (32.8) by a significant margin. This indicates its proficiency in solving real-world software engineering issues, including bug fixes and feature implementation. In TerminalBench, which evaluates terminal command execution competence, LongCat-Flash-Lite secures a leading score of 33.75, far exceeding Qwen3-Next-80B-A3B-Instruct (15.19), Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite (20.0) and Kimi-Linear-48B-A3B (20.0), reflecting its robust ability to understand and execute terminal-related instructions critical for developer-centric agentic applications. Additionally, in SWE-Bench Multilingual—a benchmark designed to measure cross-language programming generalization across diverse software ecosystems— LongCat-Flash-Lite achieves a strong accuracy of 38.10, outperforming Qwen3-Next-80B-A3B-Instruct (31.3) and Kimi-Linear-48B-A3B (37.2), thus demonstrating its reliable adaptability to multi-language development scenarios. In PRDBench, LongCat-Flash-Lite achieves a score of 39.63, significantly outperforming Qwen3-Next-80B-A3B-Instruct (15.36). We observe that our model can autonomously write unit tests to verify its development, producing higher-quality code repositories.

General Domains. LongCat-Flash-Lite delivers balanced and competitive performance in general domain knowledge tasks. On MMLU, it scores 85.52, which is comparable to Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite (84.68) and Kimi-Linear-48B-A3B (79.91), and only slightly lower than Qwen3-Next-80B-A3B-Instruct (89.28). In Chinese-specific benchmarks (CEval and CMMLU), it achieves 86.55 and 82.48 respectively, performing particularly well against Kimi-Linear-48B-A3B (78.48 and 76.26) and Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite (75.16 and 72.06). On GPQA-Diamond, it scores 66.78, maintaining competitiveness within the benchmark’s performance range. For MMLU-Pro, it achieves 78.29, demonstrating solid performance in handling more challenging multi-task language understanding questions.

Mathematical Reasoning. LongCat-Flash-Lite exhibits strong mathematical reasoning capabilities across both basic and advanced tasks. On MATH500, it achieves an accuracy of 96.80, which is close to Qwen3-Next-80B-A3B-Instruct (98.00), and outperforms Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite (95.20). In advanced mathematical competition benchmarks, it delivers impressive results: AIME24 (72.19) and AIME25 (63.23). These scores surpass Kimi-Linear-48B-A3B (70.52 and 59.58) and Gemini 2.5 Flash-Lite (63.33 and 50.1), highlighting its ability to handle complex, multi-step mathematical deduction.

6.4 Fast Inference with Optimized Kernels

As discussed in Section 4, the extreme activation sparsity of this model necessitates a large effective batch size to fully saturate GPU memory bandwidth. To achieve this, we deploy the model using "Eagle3" [36] with a "3-step speculative decoding strategy". Similarly to [37] and [11], we adopt wide EP (Expert Parallel) and SBO (Single Batch Overlap) to accelerate inference speed. While the above optimizations successfully expands the effective batch size, the model's lightweight nature shifts the bottleneck towards kernel launch overheads, making it challenging to maintain high GPU occupancy. To address this and minimize end-to-end latency, we implement the following system-level optimizations:

Kernel Optimization

- Kernel Fusion: We apply extensive kernel fusion to reduce execution overhead and memory traffic. Specifically, all intra-TP-group communication operations are fused with subsequent fine-grained kernels (e.g.,

AllReduce+Residual Add+RMSNorm,AllGather+Q-Norm+KV-Norm, andReduceScatter+RMSNorm+Hidden State Combine). For the quantized model, we integrate every activation quantization step into existing operators, including the aforementioned communication-fusion kernels and theSwiGLUcomponent. Additionally, the processing of router logits (Softmax+TopK+router scaling) and zero-expert selection is consolidated into a single unified kernel. - Optimized Attention Combine: We employ a splitkv-and-combine strategy during decoding phase. When the number of KV splits is high, the combine operation can incur significant latency, sometimes comparable to the computation itself. By optimizing the combine kernel, we effectively reduce its latency by 50%.

PDL (Programmatic Dependent Launch)

We utilize PDL [38] to allow dependent kernels to overlap their execution by triggering early launches. This mechanism not only eliminates the gaps between consecutive kernels but also improves SM utilization.

Building upon these optimizations, we achieve the exceptional inference performance illustrated in Figure 8b.

7. Conclusions

In this technical report, we presented a comprehensive study on the scalability and efficiency of embedding scaling in LLMs. Through systematic analysis of architectural constraints and comparative scaling laws, we demonstrated that scaling embeddings yields a superior Pareto frontier compared to increasing expert numbers in specific regimes, while our proposed system optimizations, including the N-gram Cache and synchronized kernels, effectively resolve associated I/O bottlenecks. Validating these findings, we introduced LongCat-Flash-Lite, a 68.5B MoE model with over 30B N-gram Embedding parameters, which not only outperforms parameter-equivalent MoE baselines but also exhibits competitive performance in agentic and coding tasks, thereby establishing a robust and efficient framework for future model scaling.

8. Acknowledgement

We extend our sincere gratitude to both the infrastructure team and evaluation team for their invaluable support and constructive feedback throughout this project. The primary contributors from these teams include:

| Linsen Guo | Lin Qiu | Xiao Liu | Yaoming Zhu |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mengxia Shen | Zijian Zhang | Xiaoyu Li | Chao Zhang |

| Yunke Zhao | Dengchang Zhao | Yifan Lu |

References

[1] Hongzhi Huang et al. (2025). Over-Tokenized Transformer: Vocabulary is Generally Worth Scaling. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.16975.

[2] Dmitry Lepikhin et al. (2021). GShard: Scaling Giant Models with Conditional Computation and Automatic Sharding. In 9th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2021, Virtual Event, Austria, May 3-7, 2021. https://openreview.net/forum?id=qrwe7XHTmYb.

[3] Samira Abnar et al. (2025). Parameters vs FLOPs: Scaling Laws for Optimal Sparsity for Mixture-of-Experts Language Models. In Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2025, Vancouver, BC, Canada, July 13-19, 2025. https://openreview.net/forum?id=l9FVZ7NXmm.

[4] Tao et al. (2024). Scaling laws with vocabulary: Larger models deserve larger vocabularies. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 37. pp. 114147–114179.

[5] Google DeepMind (2025). Gemma 3n. https://deepmind.google/models/gemma/gemma-3n/. Accessed: 2026-01-16.

[6] Ranajoy Sadhukhan et al. (2026). STEM: Scaling Transformers with Embedding Modules. https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.10639.

[7] bcml-labs (2025). ROSA+: RWKV's ROSA implementation with fallback statistical predictor. https://github.com/bcml-labs/rosa-plus. Accessed: 2026-01-23.

[8] Clark et al. (2022). Canine: Pre-training an Efficient Tokenization-Free Encoder for Language Representation. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 10. pp. 73–91. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00448. https://aclanthology.org/2022.tacl-1.5/.

[9] Pagnoni et al. (2025). Byte Latent Transformer: Patches Scale Better Than Tokens. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). pp. 9238–9258. doi:10.18653/v1/2025.acl-long.453. https://aclanthology.org/2025.acl-long.453/.

[10] Cheng et al. (2026). Conditional Memory via Scalable Lookup: A New Axis of Sparsity for Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2601.07372.

[11] Meituan (2025). LongCat-Flash Technical Report. https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.01322.

[12] Sho Takase et al. (2025). Spike No More: Stabilizing the Pre-training of Large Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.16903.

[13] Google DeepMind (2024). Gemma 3n documentation. https://ai.google.dev/gemma/docs/gemma-3n. Accessed: 2025-09-04.

[14] Bowen Peng et al. (2023). YaRN: Efficient Context Window Extension of Large Language Models. ArXiv. abs/2309.00071. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:261493986.

[15] Dan Hendrycks et al. (2021). Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.03300. arXiv:2009.03300.

[16] Yubo Wang et al. (2024). MMLU-Pro: A More Robust and Challenging Multi-Task Language Understanding Benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.01574. arXiv:2406.01574.

[17] Huang et al. (2023). C-Eval: A Multi-Level Multi-Discipline Chinese Evaluation Suite for Foundation Models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

[18] Haonan Li et al. (2023). CMMLU: Measuring massive multitask language understanding in Chinese. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.09212. arXiv:2306.09212.

[19] Suzgun et al. (2023). Challenging BIG-Bench Tasks and Whether Chain-of-Thought Can Solve Them. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023.

[20] M-A-P Team, ByteDance. (2025). SuperGPQA: Scaling LLM evaluation across 285 graduate disciplines. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.14739.

[21] Dheeru Dua et al. (2019). DROP: A Reading Comprehension Benchmark Requiring Discrete Reasoning Over Paragraphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.00161. arXiv:1903.00161.

[22] Cobbe et al. (2021). Training Verifiers to Solve Math Word Problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168.

[23] Jiawei Liu et al. (2024). Evaluating Language Models for Efficient Code Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.06450. arXiv:2408.06450.

[24] Federico Cassano et al. (2022). MultiPL-E: A Scalable and Extensible Approach to Benchmarking Neural Code Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.08227. arXiv:2208.08227.

[25] Terry Yue Zhuo et al. (2025). BigCodeBench: Benchmarking Code Generation with Diverse Function Calls and Complex Instructions. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.15877.

[26] Victor Barres et al. (2025). $\tau^2$-bench: Evaluating conversational agents in a dual-control environment. CoRR. abs/2506.07982.

[27] He et al. (2025). VitaBench: Benchmarking LLM Agents with Versatile Interactive Tasks in Real-world Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.26490.

[28] Jimenez et al. (2023). Swe-bench: Can language models resolve real-world github issues?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06770.

[29] Mike A. Merrill et al. (2026). Terminal-Bench: Benchmarking Agents on Hard, Realistic Tasks in Command Line Interfaces. https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.11868.

[30] John Yang et al. (2025). SWE-smith: Scaling Data for Software Engineering Agents. https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.21798.

[31] Fu et al. (2025). Automatically Benchmarking LLM Code Agents through Agent-Driven Annotation and Evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.24358.

[32] Rein et al. (2024). Gpqa: A graduate-level google-proof q&a benchmark. In First Conference on Language Modeling.

[33] Lightman et al. (2023). Let's verify step by step. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations.

[34] MAA (2024). AIME 2024. https://maa.org/math-competitions/american-invitational-mathematics-examination-aime.

[35] MAA (2025). AIME 2025. https://artofproblemsolving.com/wiki/index.php/AIMEProblemsandSolutions.

[36] Yuhui Li et al. (2025). EAGLE-3: Scaling up Inference Acceleration of Large Language Models via Training-Time Test. https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.01840.

[37] Yulei Qian et al. (2025). EPS-MoE: Expert Pipeline Scheduler for Cost-Efficient MoE Inference. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.12247.

[38] NVIDIA (2026). Programmatic Dependent Launch and Synchronization. https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/cuda-programming-guide/04-special-topics/programmatic-dependent-launch.html. Accessed: 2026-01-27. [39] W. Ronny Huang et al. (2021). Lookup-table recurrent language models for long tail speech recognition. In Interspeech 2021.