GQA: Training Generalized Multi-Query Transformer Models from Multi-Head Checkpoints

Joshua Ainslie${}^{}$, James Lee-Thorp${}^{}$, Michiel de Jong${}^{* \dagger}$

Yury Zemlyanskiy, Federico Lebrón, Sumit Sanghai

Google Research

${}^{*}$ Equal contribution.

${}^{\dag}$ University of Southern California. Work done at Google Research.

Abstract

Multi-query attention (MQA), which only uses a single key-value head, drastically speeds up decoder inference. However, MQA can lead to quality degradation, and moreover it may not be desirable to train a separate model just for faster inference. We (1) propose a recipe for uptraining existing multi-head language model checkpoints into models with MQA using 5% of original pre-training compute, and (2) introduce grouped-query attention (GQA), a generalization of multi-query attention which uses an intermediate (more than one, less than number of query heads) number of key-value heads. We show that uptrained GQA achieves quality close to multi-head attention with comparable speed to MQA.

1. Introduction

Autoregressive decoder inference is a severe bottleneck for Transformer models due to the memory bandwidth overhead from loading decoder weights and all attention keys and values at every decoding step ([1, 2, 3]). The memory bandwidth from loading keys and values can be sharply reduced through multi-query attention ([1]), which uses multiple query heads but single key and value heads.

However, multi-query attention ($\textsc{MQA}$) can lead to quality degradation and training instability, and it may not be feasible to train separate models optimized for quality and inference. Moreover, while some language models already use multi-query attention, such as PaLM ([4]), many do not, including publicly available language models such as T5 ([5]) and LLaMA ([6]).

This work contains two contributions for faster inference with large language models. First, we show that language model checkpoints with multi-head attention ($\textsc{MHA}$) can be uptrained ([7]) to use $\textsc{MQA}$ with a small fraction of original training compute. This presents a cost-effective method to obtain fast multi-query as well as high-quality $\textsc{MHA}$ checkpoints.

Second, we propose grouped-query attention ($\textsc{GQA}$), an interpolation between multi-head and multi-query attention with single key and value heads per subgroup of query heads. We show that uptrained $\textsc{GQA}$ achieves quality close to multi-head attention while being almost as fast as multi-query attention.

2. Method

2.1 Uptraining

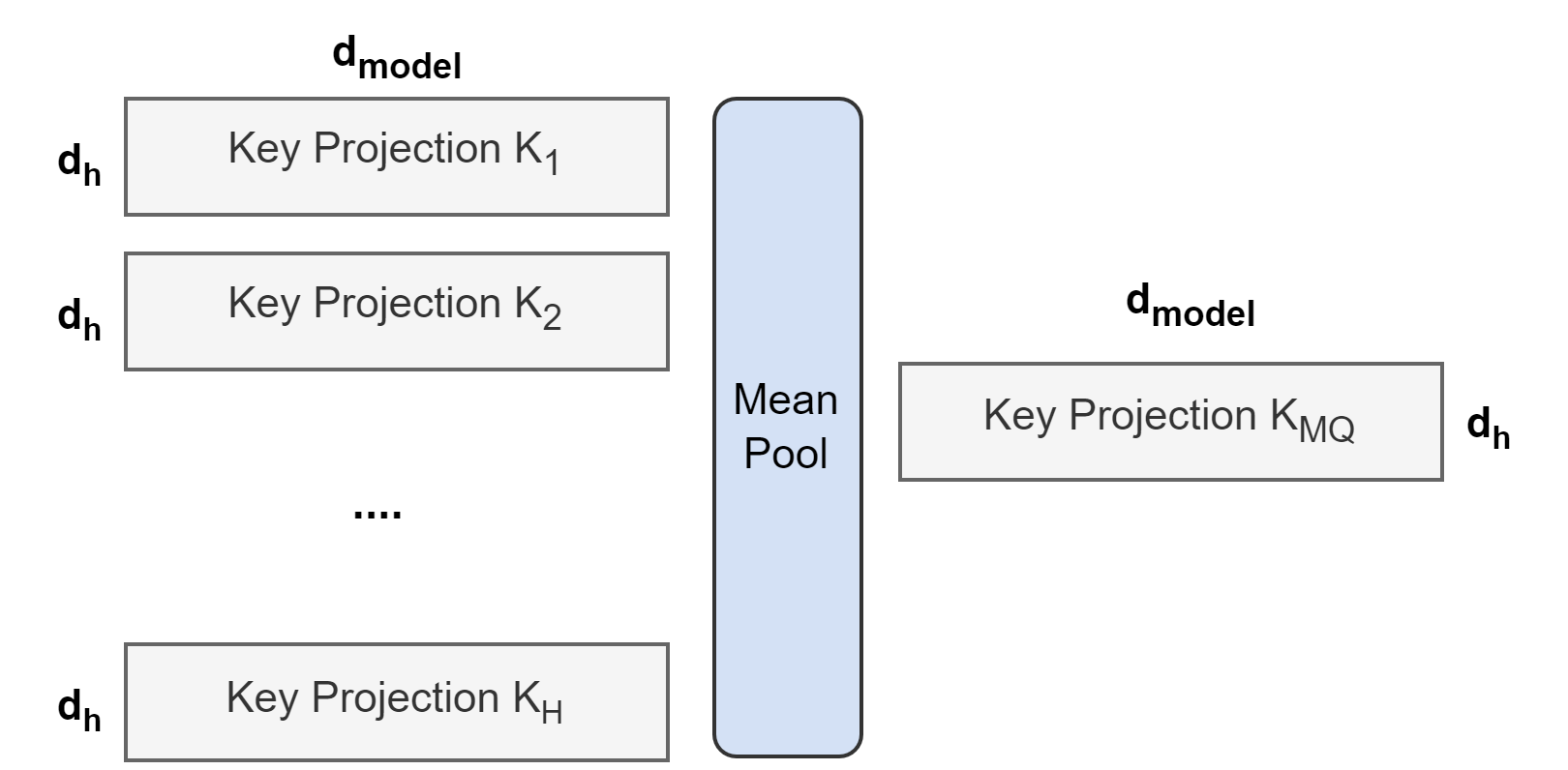

Generating a multi-query model from a multi-head model takes place in two steps: first, converting the checkpoint, and second, additional pre-training to allow the model to adapt to its new structure. Figure 1 shows the process for converting a multi-head checkpoint into a multi-query checkpoint. The projection matrices for key and value heads are mean pooled into single projection matrices, which we find works better than selecting a single key and value head or randomly initializing new key and value heads from scratch.

The converted checkpoint is then pre-trained for a small proportion $ \alpha$ of its original training steps on the same pre-training recipe.

2.2 Grouped-query attention

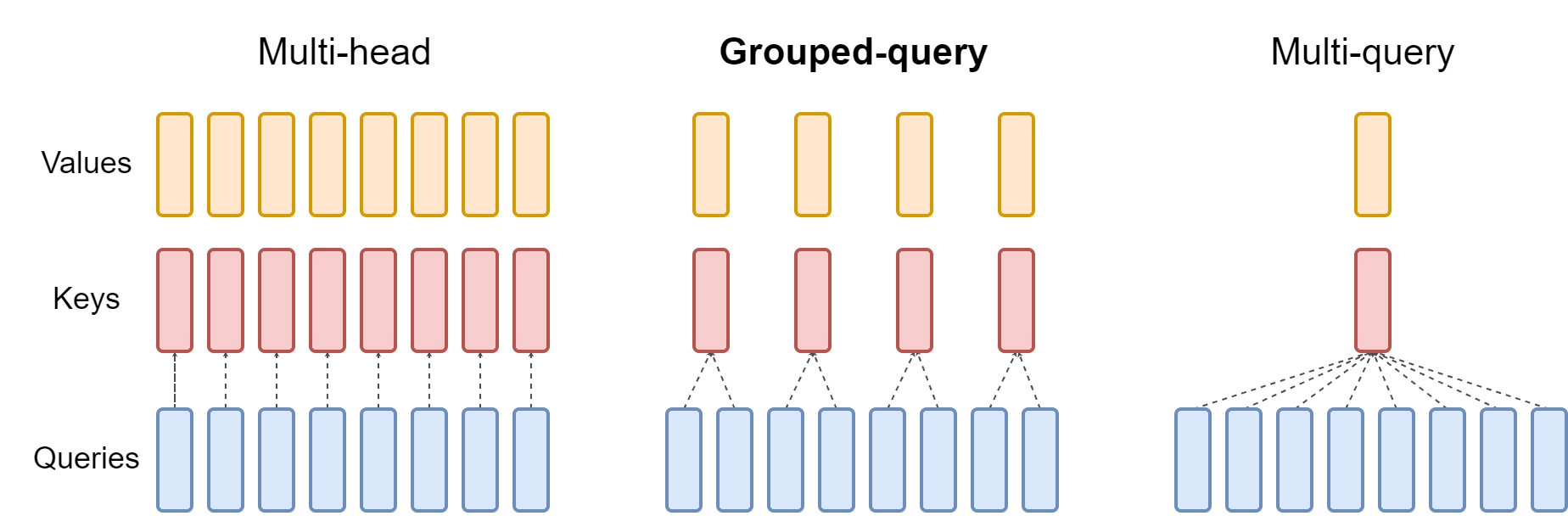

Grouped-query attention divides query heads into $G$ groups, each of which shares a single key head and value head. $\textsc{GQA}$ - $\textsc{g}$ refers to grouped-query with $G$ groups. $\textsc{GQA}$ - $1$, with a single group and therefore single key and value head, is equivalent to $\textsc{MQA}$, while $\textsc{GQA}$ - $\textsc{h}$, with groups equal to number of heads, is equivalent to $\textsc{MHA}$. Figure 2 shows a comparison of grouped-query attention and multi-head/multi-query attention. When converting a multi-head checkpoint to a $\textsc{GQA}$ checkpoint, we construct each group key and value head by mean-pooling all the original heads within that group.

An intermediate number of groups leads to an interpolated model that is higher quality than $\textsc{MQA}$ but faster than $\textsc{MHA}$, and, as we will show, represents a favorable trade-off. Going from $\textsc{MHA}$ to $\textsc{MQA}$ reduces $H$ key and value heads to a single key and value head, reducing the size of the key-value cache and therefore amount of data that needs to be loaded by a factor of $H$. However, larger models generally scale the number of heads, such that multi-query attention represents a more aggressive cut in both memory bandwidth and capacity. $\textsc{GQA}$ lets us keep the same proportional decrease in bandwidth and capacity as model size increases.

Moreover, larger models suffer relatively less from memory bandwidth overhead from attention, as the KV-cache scales with model dimension while model FLOPs and parameters scale with the square of model dimension. Finally, standard sharding for large models replicates the single key and value head by the number of model partitions ([2]); $\textsc{GQA}$ removes the waste from such partitioning. Therefore, we expect $\textsc{GQA}$ to present a particularly good trade-off for larger models.

We note that $\textsc{GQA}$ is not applied to the encoder self-attention layers; encoder representations are computed in parallel, and memory bandwidth is therefore generally not the primary bottleneck.

3. Experiments

3.1 Experimental setup

Configurations

All models are based on the T5.1.1 architecture ([5]), implemented with JAX ([8]), Flax ([9]), and Flaxformer^1. For our main experiments we consider T5 Large and XXL with multi-head attention, as well as uptrained versions of T5 XXL with multi-query and grouped-query attention. We use the Adafactor optimizer with the same hyperparameters and learning rate schedule as T5 ([5]). We apply $\textsc{MQA}$ and $\textsc{GQA}$ to decoder self-attention and cross-attention, but not encoder self-attention.

Uptraining

Uptrained models are initialized from public T5.1.1 checkpoints. The key and value heads are mean-pooled to the appropriate $\textsc{MQA}$ or $\textsc{GQA}$ structure, and then pre-trained for a further $ \alpha$ proportion of original pre-training steps with the original pre-training setup and dataset from ([5]). For $ \alpha=0.05$, training took approximately 600 TPUv3 chip-days.

Data

We evaluate on summarization datasets CNN/Daily Mail ([10]), arXiv and PubMed ([11]), MediaSum ([12]), and Multi-News ([13]); translation dataset WMT 2014 English-to-German; and question answering dataset TriviaQA ([14]). We do not evaluate on popular classification benchmarks such as GLUE ([15]) as autoregressive inference is less applicable for those tasks.

Fine-tuning

For fine-tuning, we use a constant learning rate of 0.001, batch size 128, and dropout rate 0.1 for all tasks. CNN/Daily Mail and WMT use input length of 512 and output length 256. Other summarization datasets use input length 2048 and output length 512. Finally, TriviaQA uses input length 2048 and output length 32. We train until convergence and select the checkpoint with the highest dev performance. We use greedy decoding for inference.

Timing

We report time per sample per TPUv4 chip, as measured by xprof ([16]). For timing experiments we use 8 TPUs with the largest batch size that fits up to 32 per TPU, and parallelization optimized separately for each model.

\begin{tabular}{l|cc|ccccccccc}

\toprule

\textbf{Model} & \textbf{T\textsubscript{infer}}& \textbf{Average} & \textbf{CNN} & \textbf{arXiv} & \textbf{PubMed} &\textbf{MediaSum} & \textbf{MultiNews} & \textbf{WMT} & \textbf{TriviaQA} \\

\midrule

& \textbf{s} & & \textbf{R\textsubscript{1}} & \textbf{R\textsubscript{1}} & \textbf{R\textsubscript{1}} & \textbf{R\textsubscript{1}} &\textbf{R\textsubscript{1}} & \textbf{BLEU} & \textbf{F1} \\

\midrule

\textsc{MHA}-Large & 0.37 & 46.0 & 42.9 & 44.6 & 46.2 & 35.5 & 46.6 & 27.7 & 78.2 \\

\textsc{MHA}-XXL & 1.51 & 47.2 & 43.8 & 45.6 & 47.5 & 36.4 & 46.9 & 28.4 & 81.9 \\

\textsc{MQA}-XXL & 0.24 & 46.6 & 43.0 & 45.0 & 46.9 & 36.1 & 46.5 & 28.5 & 81.3 \\

\textsc{GQA}-8-XXL & 0.28 & 47.1 & 43.5 & 45.4 & 47.7 & 36.3 & 47.2 & 28.4 & 81.6 \\

\midrule

\bottomrule

\end{tabular}

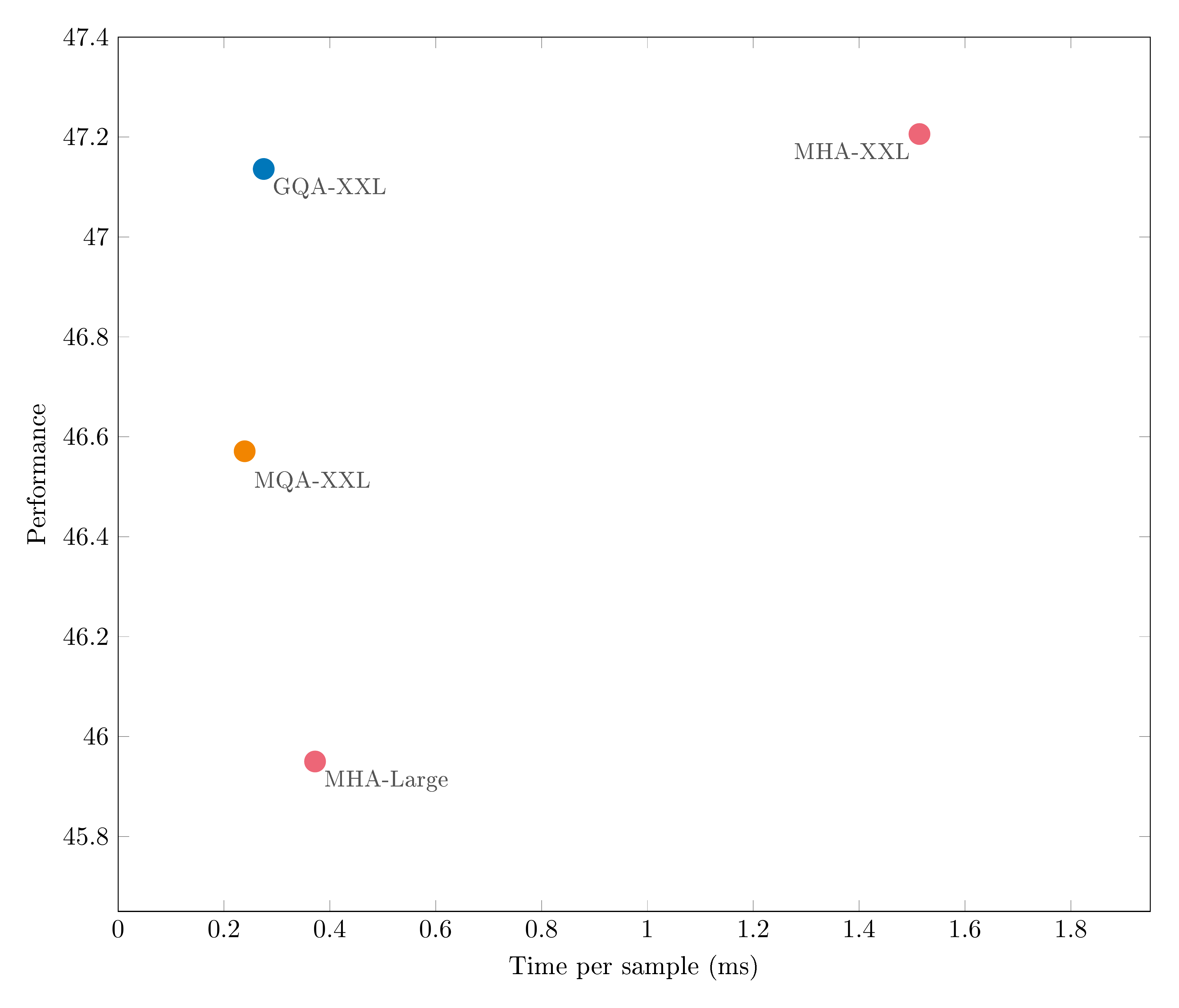

3.2 Main results

Figure 3 shows average performance over all datasets as a function of average inference time for $\textsc{MHA}$ T5-Large and T5-XXL, and uptrained $\textsc{MQA}$ and $\textsc{GQA}$ - $8$ XXL models with uptraining proportion $ \alpha = 0.05$. We see that a larger uptrained $\textsc{MQA}$ model provides a favorable trade-off relative to $\textsc{MHA}$ models, with higher quality and faster inference than $\textsc{MHA}$ -Large. Moreover, $\textsc{GQA}$ achieves significant additional quality gains, achieving performance close to $\textsc{MHA}$ -XXL with speed close to $\textsc{MQA}$. Table 1 contains full results for all datasets.

3.3 Ablations

This section presents experiments to investigate the effect of different modeling choices. We evaluate performance on a representive subsample of tasks: CNN/Daily Mail, (short-form summarization), MultiNews (long-form summarization), and TriviaQA (question-answering).

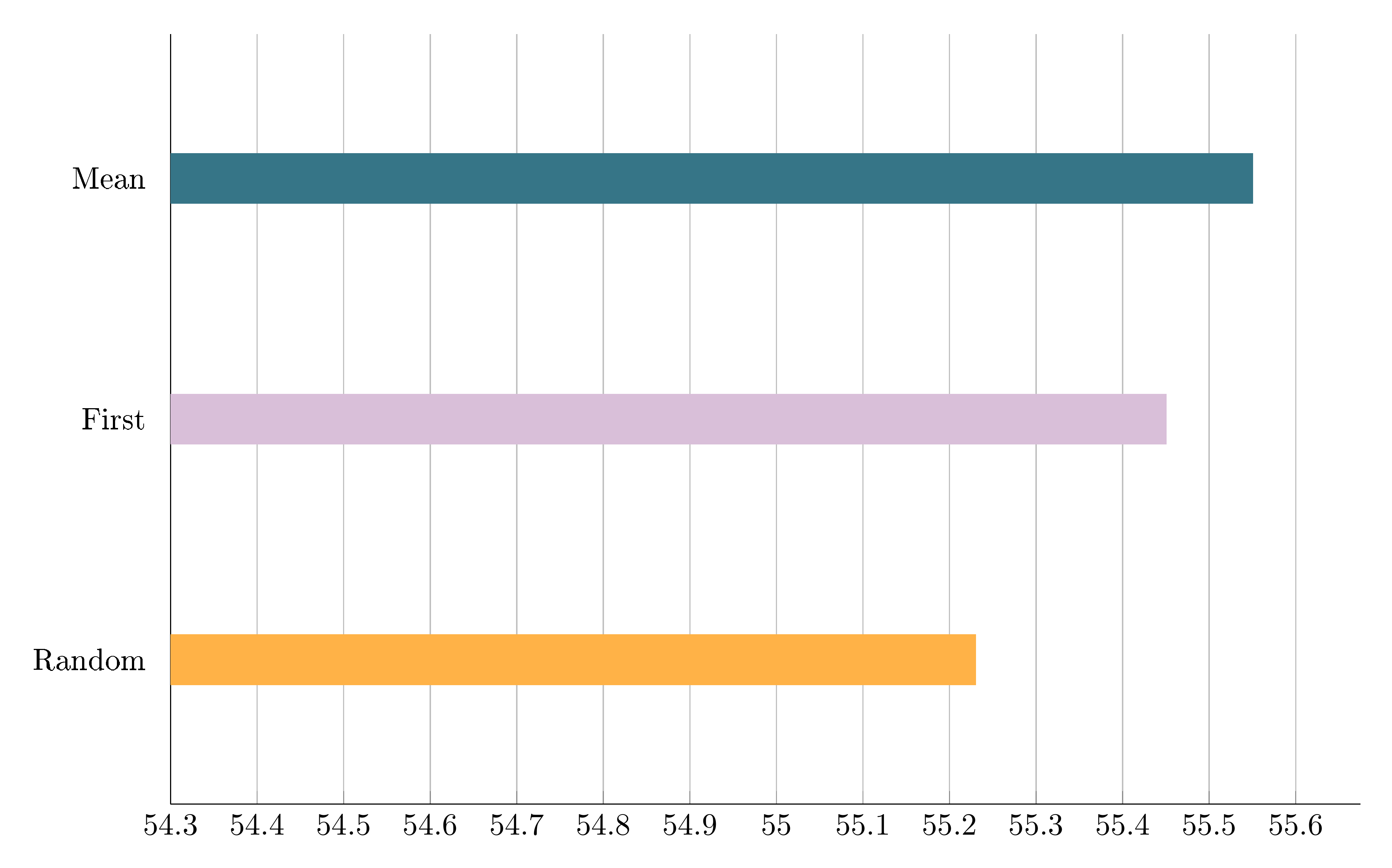

Checkpoint conversion

Figure 4 compares the performance of different methods for checkpoint conversion. Mean pooling appears to work best, followed by selecting a single head and then random initialization. Intuitively, results are ordered by the degree to which information is preserved from the pre-trained model.

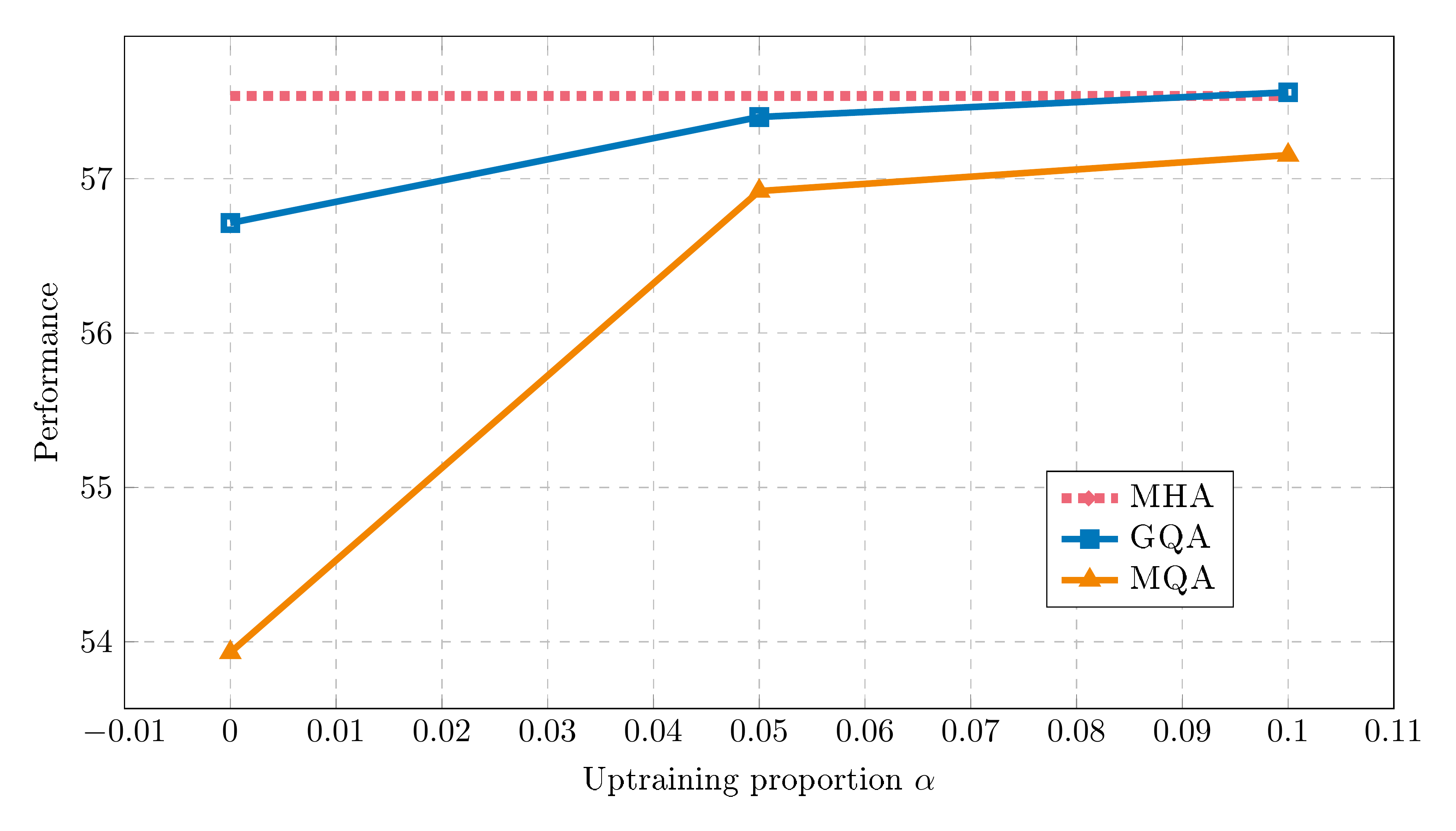

Uptraining steps

Figure 5 shows how performance varies with uptraining proportion for T5 XXL with $\textsc{MQA}$ and $\textsc{GQA}$. First, we note that $\textsc{GQA}$ already achieves reasonable performance after conversion while $\textsc{MQA}$ requires uptraining to be useful. Both $\textsc{MQA}$ and $\textsc{GQA}$ gain from 5% uptraining with diminishing returns from 10%.

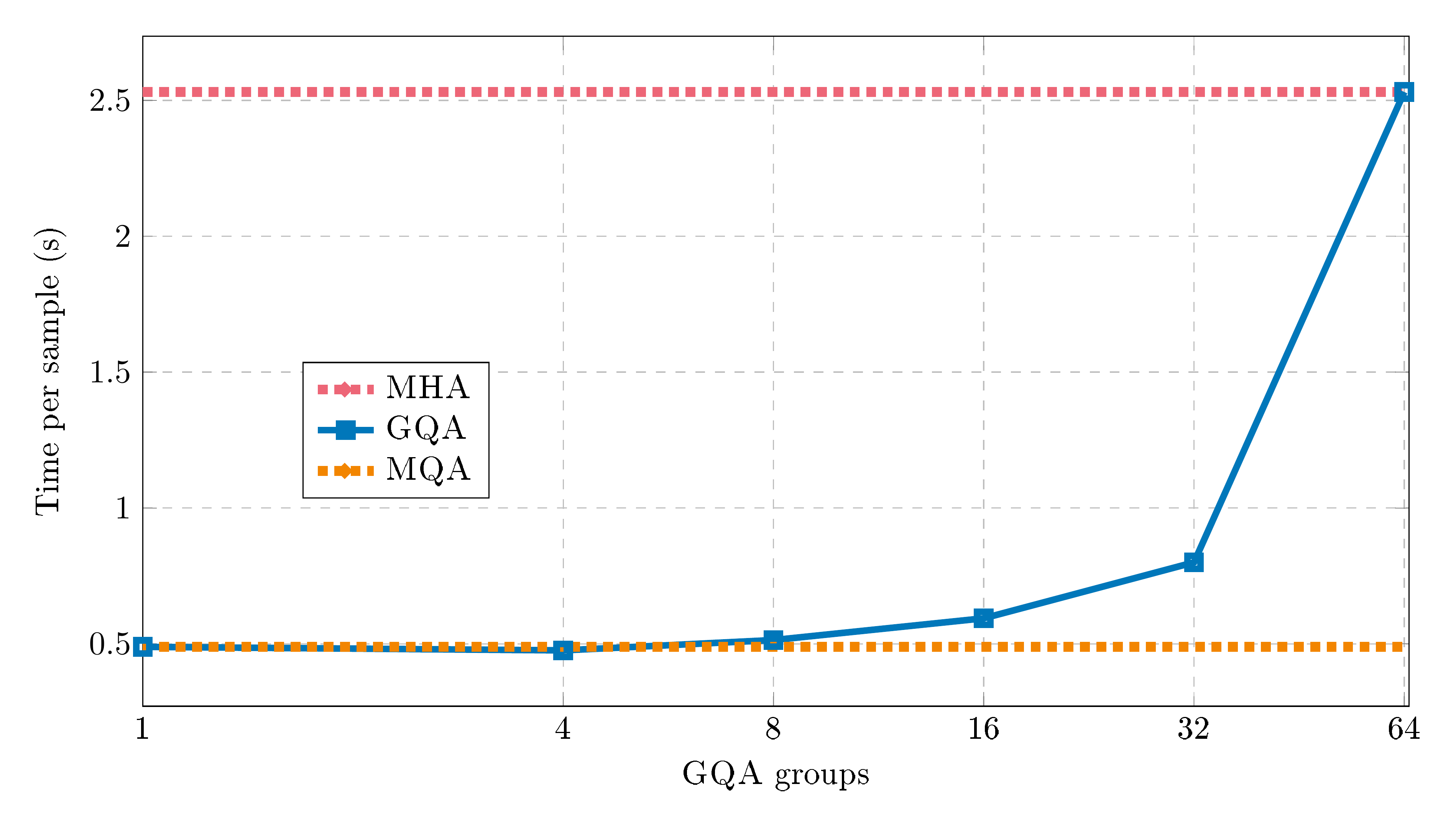

Number of groups

Figure 6 demonstrates the effect of the number of $\textsc{GQA}$ groups on inference speed. For larger models the memory bandwidth overhead from the KV cache is less constraining ([1]), while the reduction in key-value size is sharper due to the increased number of heads. As a result, increasing the number of groups from $\textsc{MQA}$ only results in modest slowdowns initially, with increasing cost as we move closer to $\textsc{MHA}$. We selected 8 groups as a favorable middle ground.

4. Related Work

This work is focused on achieving a better trade-off between decoder quality and inference time through reducing the memory bandwidth overhead ([17]) from loading keys and values. [1] first proposed reducing this overhead through multi-query attention. Follow-up work showed that multi-query attention is especially helpful for long inputs ([2, 3]). [18] independently developed GQA with public implementation. Other works have explored grouping attention heads for computational efficiency ([19, 20, 21]) without focusing specifically on key-value heads, which determine memory bandwidth overhead.

A number of other methods have been proposed to reduce memory bandwidth overhead from keys and values, as well as parameters. Flash attention ([22]) structures the attention computation to avoid materializing the quadratic attention scores, reducing memory and speeding up training. Quantization ([23, 24]) reduces the size of weights and activations, including keys and values, by lowering precision. Model distillation ([25, 26]) instead reduces model size at a given precision, using data generated from the larger model to finetune the smaller model. Layer-sparse cross-attention ([3]) eliminates most cross-attention layers which make up the primary expense for longer inputs. Speculative sampling ([27, 28]) ameliorates the memory bandwidth bottleneck by proposing multiple tokens with a smaller model which are then scored in parallel by a larger model.

Finally, the uptraining procedure we propose is inspired by [7], which uptrains standard T5 checkpoints into sparsely activated Mixture-of-Experts models.

5. Conclusion

Language models are expensive for inference primarily due to the memory bandwidth overhead from loading keys and values. Multi-query attention reduces this overhead at the cost of decreased model capacity and quality. We propose to convert multi-head attention models to multi-query models with a small fraction of original pre-training compute. Moreover, we introduce grouped-query attention, an interpolation of multi-query and multi-head attention that achieves quality close to multi-head at comparable speed to multi-query attention.

Limitations

This paper focuses on ameliorating the memory bandwidth overhead from loading keys and values. This overhead is most important when generating longer sequences, for which quality is inherently difficult to evaluate. For summarization we employ Rouge score, which we know is a flawed evaluation that does not tell the whole story; for that reason, it is difficult to be certain our trade-offs are correct. Due to limited computation, we also do not compare our XXL $\textsc{GQA}$ model to a comparitive model trained from scratch, so we do not know the relative performance of uptraining vs training from scratch. Finally, we evaluate the impact of uptraining and $\textsc{GQA}$ only on encoder-decoder models. Recently, decoder-only models are extremely popular, and since these models do not have separate self-attention and cross-attention, we expect $\textsc{GQA}$ to have a stronger advantage over $\textsc{MQA}$.

Acknowlegements

We thank Santiago Ontañón, Afroz Mohiuddin, William Cohen and others at Google Research for insightful advice and discussion.

Appendix

A. Training Stability

We find that multi-query attention can lead to training instability during fine-tuning, in particular combined with long input tasks. We trained multiple T5-Large models with multi-query attention from scratch. In each case, pre-training suffered from frequent loss spikes and the final models diverged immediately when fine-tuning on long-input tasks. Uptrained multi-query attention models are more stable but still display high variance, so for multi-query models on unstable tasks we report average performance over three fine-tuning runs. Uptrained grouped-query attention models, however, appear to be stable, so we did not investigate futher on the root causes of multi-query instability.

References

[1] Noam Shazeer. 2019. Fast transformer decoding: One write-head is all you need. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.02150.

[2] Reiner Pope, Sholto Douglas, Aakanksha Chowdhery, Jacob Devlin, James Bradbury, Anselm Levskaya, Jonathan Heek, Kefan Xiao, Shivani Agrawal, and Jeff Dean. 2022. Efficiently scaling transformer inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.05102.

[3] Michiel de Jong, Yury Zemlyanskiy, Joshua Ainslie, Nicholas FitzGerald, Sumit Sanghai, Fei Sha, and William Cohen. 2022. \href https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.08153 FiDO: Fusion-in-decoder optimized for stronger performance and faster inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.08153.

[4] Aakanksha Chowdhery, Sharan Narang, Jacob Devlin, Maarten Bosma, Gaurav Mishra, Adam Roberts, Paul Barham, Hyung Won Chung, Charles Sutton, Sebastian Gehrmann, Parker Schuh, Kensen Shi, Sasha Tsvyashchenko, Joshua Maynez, Abhishek Rao, Parker Barnes, Yi Tay, Noam Shazeer, Vinodkumar Prabhakaran, Emily Reif, Nan Du, Ben Hutchinson, Reiner Pope, James Bradbury, Jacob Austin, Michael Isard, Guy Gur-Ari, Pengcheng Yin, Toju Duke, Anselm Levskaya, Sanjay Ghemawat, Sunipa Dev, Henryk Michalewski, Xavier Garcia, Vedant Misra, Kevin Robinson, Liam Fedus, Denny Zhou, Daphne Ippolito, David Luan, Hyeontaek Lim, Barret Zoph, Alexander Spiridonov, Ryan Sepassi, David Dohan, Shivani Agrawal, Mark Omernick, Andrew M. Dai, Thanumalayan Sankaranarayana Pillai, Marie Pellat, Aitor Lewkowycz, Erica Moreira, Rewon Child, Oleksandr Polozov, Katherine Lee, Zongwei Zhou, Xuezhi Wang, Brennan Saeta, Mark Diaz, Orhan Firat, Michele Catasta, Jason Wei, Kathy Meier-Hellstern, Douglas Eck, Jeff Dean, Slav Petrov, and Noah Fiedel. 2022. \href https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2204.02311 Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways.

[5] Colin Raffel, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J. Liu. 2020. \href http://jmlr.org/papers/v21/20-074.html Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res., 21:140:1–140:67.

[6] Hugo Touvron, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix, Baptiste Rozière, Naman Goyal, Eric Hambro, Faisal Azhar, Aurelien Rodriguez, Armand Joulin, Edouard Grave, and Guillaume Lample. 2023. \href https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2302.13971 Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models.

[7] Aran Komatsuzaki, Joan Puigcerver, James Lee-Thorp, Carlos Riquelme Ruiz, Basil Mustafa, Joshua Ainslie, Yi Tay, Mostafa Dehghani, and Neil Houlsby. 2022. \href https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2212.05055 Sparse upcycling: Training mixture-of-experts from dense checkpoints.

[8] James Bradbury, Roy Frostig, Peter Hawkins, Matthew James Johnson, Chris Leary, Dougal Maclaurin, George Necula, Adam Paszke, Jake VanderPlas, Skye Wanderman-Milne, and Qiao Zhang. 2018. \href http://github.com/google/jax JAX: composable transformations of Python+NumPy programs.

[9] Jonathan Heek, Anselm Levskaya, Avital Oliver, Marvin Ritter, Bertrand Rondepierre, Andreas Steiner, and Marc van Zee. 2020. \href http://github.com/google/flax Flax: A neural network library and ecosystem for JAX.

[10] Ramesh Nallapati, Bowen Zhou, C'ıcero Nogueira dos Santos, Çaglar Gülçehre, and Bing Xiang. 2016. \href https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/k16-1028 Abstractive text summarization using sequence-to-sequence rnns and beyond. In Proceedings of the 20th SIGNLL Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, CoNLL 2016, Berlin, Germany, August 11-12, 2016, pages 280–290. ACL.

[11] Arman Cohan, Franck Dernoncourt, Doo Soon Kim, Trung Bui, Seokhwan Kim, Walter Chang, and Nazli Goharian. 2018. \href https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N18-2097 A discourse-aware attention model for abstractive summarization of long documents. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers), pages 615–621, New Orleans, Louisiana. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[12] Chenguang Zhu, Yang Liu, Jie Mei, and Michael Zeng. 2021. \href https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.naacl-main.474 Mediasum: A large-scale media interview dataset for dialogue summarization. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, NAACL-HLT 2021, Online, June 6-11, 2021, pages 5927–5934. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[13] Alexander R. Fabbri, Irene Li, Tianwei She, Suyi Li, and Dragomir R. Radev. 2019. \href https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/p19-1102 Multi-news: A large-scale multi-document summarization dataset and abstractive hierarchical model. In Proceedings of the 57th Conference of the Association for Computational Linguistics, ACL 2019, Florence, Italy, July 28- August 2, 2019, Volume 1: Long Papers, pages 1074–1084. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[14] Mandar Joshi, Eunsol Choi, Daniel S. Weld, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2017. Triviaqa: A large scale distantly supervised challenge dataset for reading comprehension. In Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Vancouver, Canada. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[15] Alex Wang, Amanpreet Singh, Julian Michael, Felix Hill, Omer Levy, and Samuel R. Bowman. 2019. \href https://openreview.net/forum?id=rJ4km2R5t7 GLUE: A multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. In 7th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2019, New Orleans, LA, USA, May 6-9, 2019. OpenReview.net.

[16] Google. 2020. Profile your model with cloud tpu tools. https://cloud.google.com/tpu/docs/cloud-tpu-tools. Accessed: 2022-11-11.

[17] Samuel Williams, Andrew Waterman, and David A. Patterson. 2009. \href https://doi.org/10.1145/1498765.1498785 Roofline: an insightful visual performance model for multicore architectures. Commun. ACM, 52(4):65–76.

[18] Markus Rabe. 2023. Memory-efficient attention. https://github.com/google/flaxformer/blob/main/flaxformer/components/attention/memory_efficient_attention.py. Accessed: 2023-05-23.

[19] Sungrae Park, Geewook Kim, Junyeop Lee, Junbum Cha, Ji-Hoon Kim, and Hwalsuk Lee. 2020. \href https://doi.org/10.18653/V1/2020.COLING-MAIN.607 Scale down transformer by grouping features for a lightweight character-level language model. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, COLING 2020, Barcelona, Spain (Online), December 8-13, 2020, pages 6883–6893. International Committee on Computational Linguistics.

[20] Gen Luo, Yiyi Zhou, Xiaoshuai Sun, Yan Wang, Liujuan Cao, Yongjian Wu, Feiyue Huang, and Rongrong Ji. 2022. \href https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2021.3139234 Towards lightweight transformer via group-wise transformation for vision-and-language tasks. IEEE Trans. Image Process., 31:3386–3398.

[21] Jinjie Ni, Rui Mao, Zonglin Yang, Han Lei, and Erik Cambria. 2023. \href https://doi.org/10.18653/V1/2023.ACL-LONG.812 Finding the pillars of strength for multi-head attention. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), ACL 2023, Toronto, Canada, July 9-14, 2023, pages 14526–14540. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[22] Tri Dao, Daniel Y. Fu, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. 2022. \href https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.14135 Flashattention: Fast and memory-efficient exact attention with io-awareness. CoRR, abs/2205.14135.

[23] Tim Dettmers, Mike Lewis, Younes Belkada, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2022. \href https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2208.07339 Llm.int8(): 8-bit matrix multiplication for transformers at scale. CoRR, abs/2208.07339.

[24] Elias Frantar, Saleh Ashkboos, Torsten Hoefler, and Dan Alistarh. 2022. \href https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.17323 GPTQ: accurate post-training quantization for generative pre-trained transformers. CoRR, abs/2210.17323.

[25] Geoffrey E. Hinton, Oriol Vinyals, and Jeffrey Dean. 2015. \href http://arxiv.org/abs/1503.02531 Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. CoRR, abs/1503.02531.

[26] Jianping Gou, Baosheng Yu, Stephen J. Maybank, and Dacheng Tao. 2021. \href https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-021-01453-z Knowledge distillation: A survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis., 129(6):1789–1819.

[27] Charlie Chen, Sebastian Borgeaud, Geoffrey Irving, Jean-Baptiste Lespiau, Laurent Sifre, and John Jumper. 2023. \href https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.01318 Accelerating large language model decoding with speculative sampling. CoRR, abs/2302.01318.

[28] Yaniv Leviathan, Matan Kalman, and Yossi Matias. 2022. \href https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.17192 Fast inference from transformers via speculative decoding. CoRR, abs/2211.17192.