References

[1] Colin Raffel, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J. Liu. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. JMLR, 2020.

[2] Tom B. Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Sandhini Agarwal, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Gretchen Krueger, Tom Henighan, Rewon Child, Aditya Ramesh, Daniel M. Ziegler, Jeffrey Wu, Clemens Winter, Christopher Hesse, Mark Chen, Eric Sigler, Mateusz Litwin, Scott Gray, Benjamin Chess, Jack Clark, Christopher Berner, Sam McCandlish, Alec Radford, Ilya Sutskever, and Dario Amodei. Language models are few-shot learners. In NeurIPS, 2020.

[3] Kaiming He, Georgia Gkioxari, Piotr Dollar, and Ross Girshick. Mask R-CNN. In ICCV, 2017.

[4] Jiasen Lu, Dhruv Batra, Devi Parikh, and Stefan Lee. Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks. In NeurIPS, 2019.

[5] Liunian Harold Li, Mark Yatskar, Da Yin, Cho-Jui Hsieh, and Kai-Wei Chang. Visualbert: A simple and performant baseline for vision and language. In arXiv, 2019.

[6] Hao Tan and Mohit Bansal. Lxmert: Learning cross-modality encoder representations from transformers. In EMNLP, 2019.

[7] Ronghang Hu and Amanpreet Singh. Unit: Multimodal multitask learning with a unified transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp.\ 1439–1449, 2021.

[8] Jaemin Cho, Jie Lei, Hao Tan, and Mohit Bansal. Unifying vision-and-language tasks via text generation. In ICML, 2021.

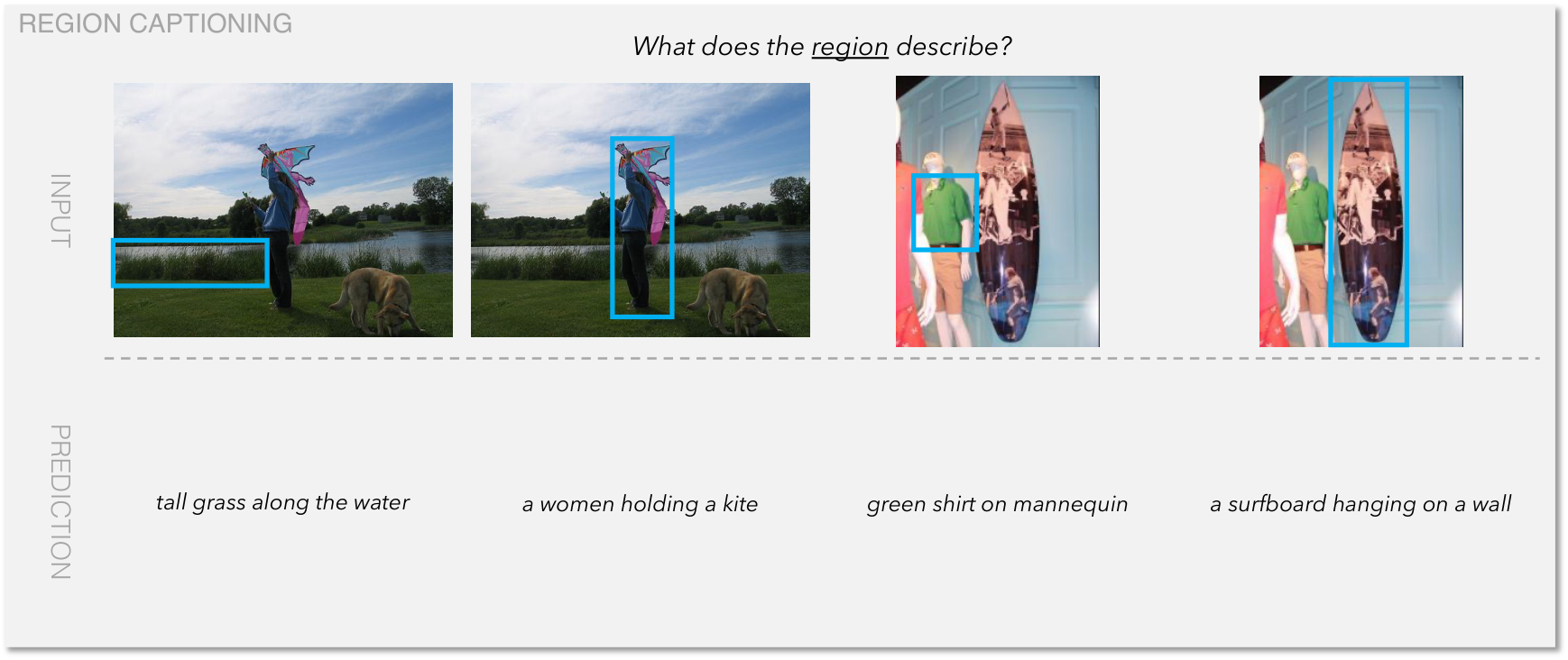

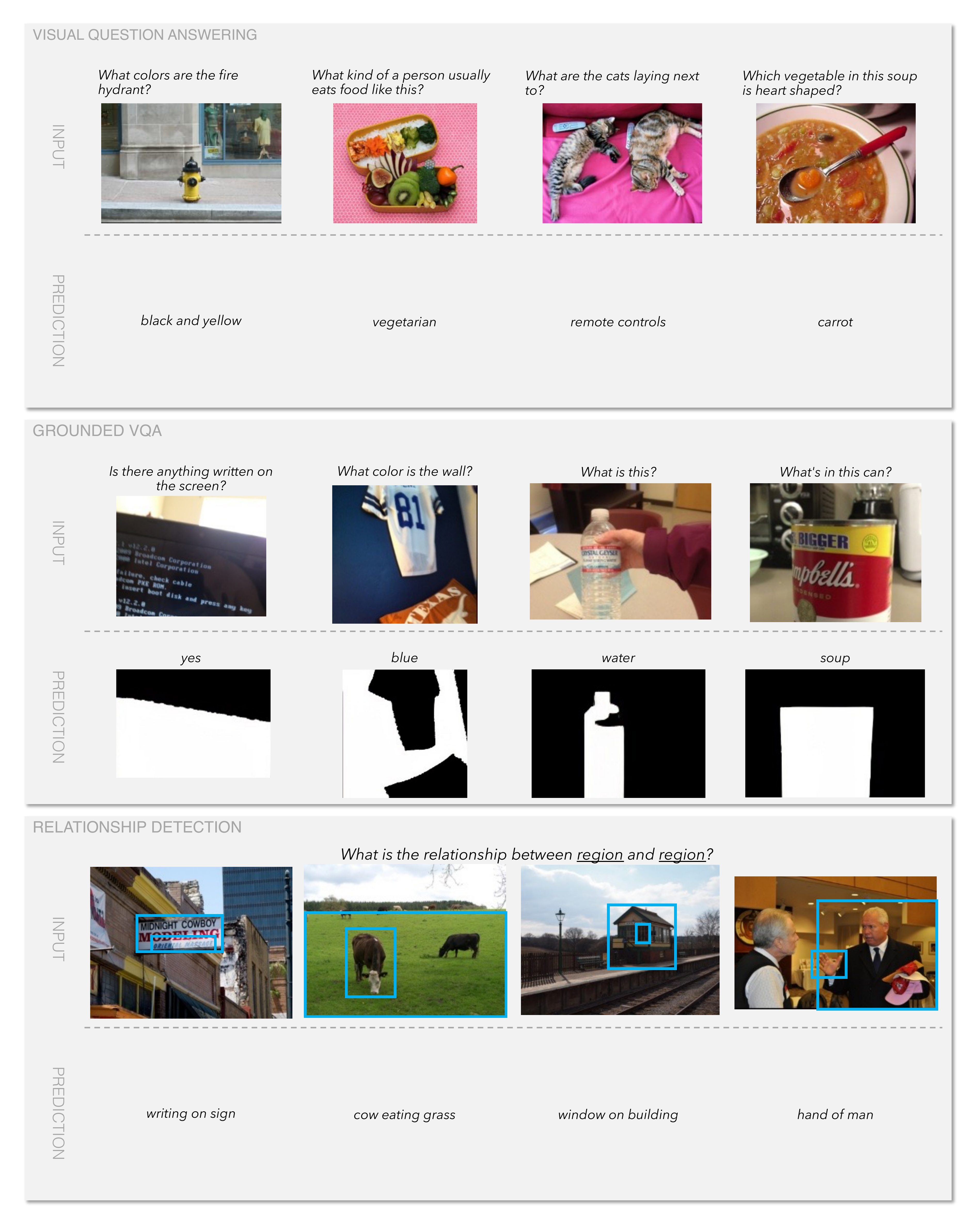

[9] Tanmay Gupta, Amita Kamath, Aniruddha Kembhavi, and Derek Hoiem. Towards general purpose vision systems: An end-to-end task-agnostic vision-language architecture. In CVPR, 2022a.

[10] Peng Wang, An Yang, Rui Men, Junyang Lin, Shuai Bai, Zhikang Li, Jianxin Ma, Chang Zhou, Jingren Zhou, and Hongxia Yang. Unifying architectures, tasks, and modalities through a simple sequence-to-sequence learning framework. arXiv, 2022b.

[11] Patrick Esser, Robin Rombach, and Bjorn Ommer. Taming transformers for high-resolution image synthesis. In CVPR, 2021.

[12] Tanmay Gupta, Ryan Marten, Aniruddha Kembhavi, and Derek Hoiem. GRIT: General robust image task benchmark. arXiv, 2022b.

[13] Karan Desai, Gaurav Kaul, Zubin Aysola, and Justin Johnson. RedCaps: Web-curated image-text data created by the people, for the people. arXiv, 2021.

[14] Ranjay Krishna, Yuke Zhu, Oliver Groth, Justin Johnson, Kenji Hata, Joshua Kravitz, Stephanie Chen, Yannis Kalantidis, Li-Jia Li, David A. Shamma, Michael S. Bernstein, and Fei-Fei Li. Visual genome: Connecting language and vision using crowdsourced dense image annotations. IJCV, 2017.

[15] Agrim Gupta, Piotr Dollar, and Ross Girshick. LVIS: A dataset for large vocabulary instance segmentation. In CVPR, 2019.

[16] Alina Kuznetsova, Hassan Rom, Neil Alldrin, Jasper Uijlings, Ivan Krasin, Jordi Pont-Tuset, Shahab Kamali, Stefan Popov, Matteo Malloci, Alexander Kolesnikov, Tom Duerig, and Vittorio Ferrari. The open images dataset v4: Unified image classification, object detection, and visual relationship detection at scale. IJCV, 2020.

[17] Anthony D Rhodes, Max H Quinn, and Melanie Mitchell. Fast on-line kernel density estimation for active object localization. In 2017 international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), pp.\ 454–462. IEEE, 2017.

[18] Tsung-Yi Lin, Michael Maire, Serge Belongie, James Hays, Pietro Perona, Deva Ramanan, Piotr Dollár, and C Lawrence Zitnick. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In ECCV, 2014.

[19] Sahar Kazemzadeh, Vicente Ordonez, Mark Matten, and Tamara Berg. Referitgame: Referring to objects in photographs of natural scenes. In EMNLP, 2014.

[20] Pushmeet Kohli Nathan Silberman, Derek Hoiem and Rob Fergus. Indoor segmentation and support inference from RGBD images. In ECCV, 2012.

[21] Gwangbin Bae, Ignas Budvytis, and Roberto Cipolla. Estimating and exploiting the aleatoric uncertainty in surface normal estimation. In ICCV, 2021.

[22] J. Deng, W. Dong, R. Socher, L.-J. Li, K. Li, and L. Fei-Fei. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In CVPR, 2009.

[23] Axel Pinz et al. Object categorization. Foundations and Trends® in Computer Graphics and Vision, 1(4):255–353, 2006.

[24] Xinlei Chen, Hao Fang, Tsung-Yi Lin, Ramakrishna Vedantam, Saurabh Gupta, Piotr Dollár, and C Lawrence Zitnick. Microsoft coco captions: Data collection and evaluation server. arXiv, 2015.

[25] Soravit Changpinyo, Piyush Sharma, Nan Ding, and Radu Soricut. Conceptual 12m: Pushing web-scale image-text pre-training to recognize long-tail visual concepts. In CVPR, 2021.

[26] Stanislaw Antol, Aishwarya Agrawal, Jiasen Lu, Margaret Mitchell, Dhruv Batra, C. Lawrence Zitnick, and Devi Parikh. VQA: Visual Question Answering. In International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2015.

[27] Cewu Lu, Ranjay Krishna, Michael Bernstein, and Li Fei-Fei. Visual relationship detection with language priors. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 2016.

[28] Chongyan Chen, Samreen Anjum, and Danna Gurari. Grounding answers for visual questions asked by visually impaired people. In CVPR, 2022a.

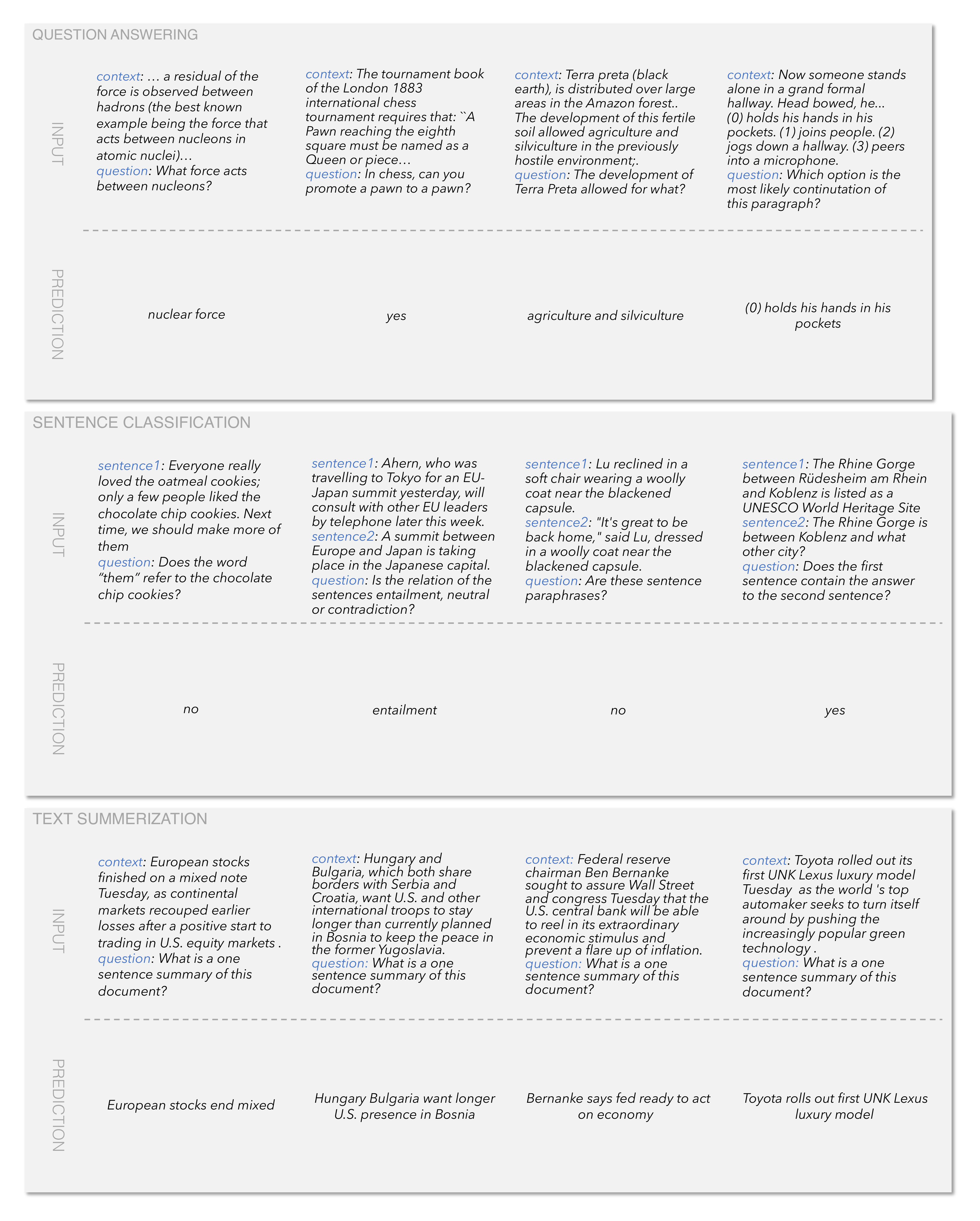

[29] Adina Williams, Nikita Nangia, and Samuel Bowman. A broad-coverage challenge corpus for sentence understanding through inference. In

Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers), pp.\ 1112–1122. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2018. URL

http://aclweb.org/anthology/N18-1101.

[30] Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. In EMNLP, 2016.

[31] David Graff, Junbo Kong, Ke Chen, and Kazuaki Maeda. English gigaword. Linguistic Data Consortium, Philadelphia, 4(1):34, 2003.

[33] Taku Kudo and John Richardson. Sentencepiece: A simple and language independent subword tokenizer and detokenizer for neural text processing. In EMNLP, 2018.

[34] Bryan McCann, Nitish Shirish Keskar, Caiming Xiong, and Richard Socher. The natural language decathlon: Multitask learning as question answering. arXiv, 2018.

[35] Ting Chen, Saurabh Saxena, Lala Li, David J Fleet, and Geoffrey Hinton. Pix2seq: A language modeling framework for object detection. In ICLR, 2022b.

[36] Alexey Dosovitskiy, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, Jakob Uszkoreit, and Neil Houlsby. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In ICLR, 2021.

[37] Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In NAACL, 2019.

[38] Jiasen Lu, Vedanuj Goswami, Marcus Rohrbach, D. Parikh, and Stefan Lee. 12-in-1: Multi-task vision and language representation learning. In CVPR, 2020.

[39] Hangbo Bao, Li Dong, and Furu Wei. BEiT: BERT pre-training of image transformers. In ICLR, 2022.

[40] Kaiming He, Xinlei Chen, Saining Xie, Yanghao Li, Piotr Dollár, and Ross Girshick. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In CVPR, 2022.

[41] Zirui Wang, Jiahui Yu, Adams Wei Yu, Zihang Dai, Yulia Tsvetkov, and Yuan Cao. Simvlm: Simple visual language model pretraining with weak supervision. In ICLR, 2022d.

[42] Tal Ridnik, Emanuel Ben-Baruch, Asaf Noy, and Lihi Zelnik-Manor. Imagenet-21k pretraining for the masses. arXiv, 2021.

[43] Alec Radford, Jong Wook Kim, Chris Hallacy, Aditya Ramesh, Gabriel Goh, Sandhini Agarwal, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Pamela Mishkin, Jack Clark, Gretchen Krueger, and Ilya Sutskever. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In ICML, 2021.

[44] Noam Shazeer and Mitchell Stern. Adafactor: Adaptive learning rates with sublinear memory cost. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp.\ 4596–4604. PMLR, 2018.

[45] Amita Kamath, Christopher Clark, Tanmay Gupta, Eric Kolve, Derek Hoiem, and Aniruddha Kembhavi. Webly supervised concept expansion for general purpose vision models. arXiv, 2022.

[46] Bolei Zhou, Agata Lapedriza, Aditya Khosla, Aude Oliva, and Antonio Torralba. Places: A 10 million image database for scene recognition. TPAMI, 2017.

[47] Yash Goyal, Tejas Khot, Douglas Summers-Stay, Dhruv Batra, and Devi Parikh. Making the V in VQA matter: Elevating the role of image understanding in visual question answering. In CVPR, 2017.

[48] Dustin Schwenk, Apoorv Khandelwal, Christopher Clark, Kenneth Marino, and Roozbeh Mottaghi. A-okvqa: A benchmark for visual question answering using world knowledge. arXiv, 2022.

[49] Danna Gurari, Qing Li, Abigale J Stangl, Anhong Guo, Chi Lin, Kristen Grauman, Jiebo Luo, and Jeffrey P Bigham. Vizwiz grand challenge: Answering visual questions from blind people. In CVPR, 2018.

[50] Sarah Pratt, Mark Yatskar, Luca Weihs, Ali Farhadi, and Aniruddha Kembhavi. Grounded situation recognition. In ECCV, 2020.

[51] Ning Xie, Farley Lai, Derek Doran, and Asim Kadav. Visual entailment: A novel task for fine-grained image understanding. arXiv, 2019.

[52] Jae Sung Park, Chandra Bhagavatula, Roozbeh Mottaghi, Ali Farhadi, and Yejin Choi. Visualcomet: Reasoning about the dynamic context of a still image. In In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2020.

[53] Harsh Agrawal, Karan Desai, Yufei Wang, Xinlei Chen, Rishabh Jain, Mark Johnson, Dhruv Batra, Devi Parikh, Stefan Lee, and Peter Anderson. nocaps: novel object captioning at scale. In ICCV, 2019.

[54] William B. Dolan and Chris Brockett. Automatically constructing a corpus of sentential paraphrases. In IWP, 2005.

[55] Christopher Clark, Kenton Lee, Ming-Wei Chang, Tom Kwiatkowski, Michael Collins, and Kristina Toutanova. Boolq: Exploring the surprising difficulty of natural yes/no questions. In NAACL, 2019.

[56] Tushar Khot, Ashish Sabharwal, and Peter Clark. Scitail: A textual entailment dataset from science question answering. In AAAI, 2018.

[57] Zhenyu Li, Xuyang Wang, Xianming Liu, and Junjun Jiang. Binsformer: Revisiting adaptive bins for monocular depth estimation. arXiv, 2022e.

[58] Alexander Kolesnikov, André Susano Pinto, Lucas Beyer, Xiaohua Zhai, Jeremiah Harmsen, and Neil Houlsby. Uvim: A unified modeling approach for vision with learned guiding codes. arXiv, 2022.

[59] Jiahui Yu, Zirui Wang, Vijay Vasudevan, Legg Yeung, Mojtaba Seyedhosseini, and Yonghui Wu. Coca: Contrastive captioners are image-text foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01917, 2022a.

[60] Jean-Baptiste Alayrac, Jeff Donahue, Pauline Luc, Antoine Miech, Iain Barr, Yana Hasson, Karel Lenc, Arthur Mensch, Katie Millican, Malcolm Reynolds, Roman Ring, Eliza Rutherford, Serkan Cabi, Tengda Han, Zhitao Gong, Sina Samangooei, Marianne Monteiro, Jacob Menick, Sebastian Borgeaud, Andrew Brock, Aida Nematzadeh, Sahand Sharifzadeh, Mikolaj Binkowski, Ricardo Barreira, Oriol Vinyals, Andrew Zisserman, and Karen Simonyan. Flamingo: a visual language model for few-shot learning. arXiv, 2022.

[61] Liangke Gui, Borui Wang, Qiuyuan Huang, Alex Hauptmann, Yonatan Bisk, and Jianfeng Gao. Kat: A knowledge augmented transformer for vision-and-language. arXiv, 2021.

[62] Marcella Cornia, Lorenzo Baraldi, Giuseppe Fiameni, and Rita Cucchiara. Universal captioner: long-tail vision-and-language model training through content-style separation. arXiv, 2021.

[63] Shaden Smith, Mostofa Patwary, Brandon Norick, Patrick LeGresley, Samyam Rajbhandari, Jared Casper, Zhun Liu, Shrimai Prabhumoye, George Zerveas, Vijay Korthikanti, Elton Zheng, Rewon Child, Reza Yazdani Aminabadi, Julie Bernauer, Xia Song, Mohammad Shoeybi, Yuxiong He, Michael Houston, Saurabh Tiwary, and Bryan Catanzaro. Using deepspeed and megatron to train megatron-turing nlg 530b, a large-scale generative language model. arXiv, 2022.

[64] Barret Zoph, Irwan Bello, Sameer Kumar, Nan Du, Yanping Huang, Jeff Dean, Noam Shazeer, and William Fedus. Designing effective sparse expert models. arXiv, 2022.

[65] Pengcheng He, Xiaodong Liu, Jianfeng Gao, and Weizhu Chen. DeBERTa: Decoding-enhanced bert with disentangled attention. In ICLR, 2021.

[66] Jiahui Yu, Yuanzhong Xu, Jing Yu Koh, Thang Luong, Gunjan Baid, Zirui Wang, Vijay Vasudevan, Alexander Ku, Yinfei Yang, Burcu Karagol Ayan, et al. Scaling autoregressive models for content-rich text-to-image generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.10789, 2022b.

[67] Junnan Li, Dongxu Li, Caiming Xiong, and Steven Hoi. Blip: Bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. In ICML, 2022b.

[68] Junnan Li, Ramprasaath Selvaraju, Akhilesh Gotmare, Shafiq Joty, Caiming Xiong, and Steven Chu Hong Hoi. Align before fuse: Vision and language representation learning with momentum distillation. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:9694–9705, 2021.

[69] Jianfeng Wang, Zhengyuan Yang, Xiaowei Hu, Linjie Li, Kevin Lin, Zhe Gan, Zicheng Liu, Ce Liu, and Lijuan Wang. Git: A generative image-to-text transformer for vision and language. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.14100, 2022a.

[70] Lu Yuan, Dongdong Chen, Yi-Ling Chen, Noel Codella, Xiyang Dai, Jianfeng Gao, Houdong Hu, Xuedong Huang, Boxin Li, Chunyuan Li, et al. Florence: A new foundation model for computer vision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.11432, 2021.

[71] Benyuan Sun, Jin Dai, Zihao Liang, Congying Liu, Yi Yang, and Bo Bai. Gppf: A general perception pre-training framework via sparsely activated multi-task learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.02148, 2022.

[72] Wenhui Wang, Hangbo Bao, Li Dong, Johan Bjorck, Zhiliang Peng, Qiang Liu, Kriti Aggarwal, Owais Khan Mohammed, Saksham Singhal, Subhojit Som, et al. Image as a foreign language: Beit pretraining for all vision and vision-language tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.10442, 2022c.

[73] Zhiliang Peng, Li Dong, Hangbo Bao, Qixiang Ye, and Furu Wei. Beit v2: Masked image modeling with vector-quantized visual tokenizers. ArXiv, abs/2208.06366, 2022.

[74] Amanpreet Singh, Ronghang Hu, Vedanuj Goswami, Guillaume Couairon, Wojciech Galuba, Marcus Rohrbach, and Douwe Kiela. Flava: A foundational language and vision alignment model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp.\ 15638–15650, 2022.

[75] Xiaodong Liu, Pengcheng He, Weizhu Chen, and Jianfeng Gao. Multi-task deep neural networks for natural language understanding. In

Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp.\ 4487–4496. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019. URL

https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P19-1441.

[76] Aakanksha Chowdhery, Sharan Narang, Jacob Devlin, Maarten Bosma, Gaurav Mishra, Adam Roberts, Paul Barham, Hyung Won Chung, Charles Sutton, Sebastian Gehrmann, et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.02311, 2022.

[77] Wenhui Wang, Hangbo Bao, Li Dong, and Furu Wei. Vlmo: Unified vision-language pre-training with mixture-of-modality-experts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.02358, 2021.

[78] Lukasz Kaiser, Aidan N Gomez, Noam Shazeer, Ashish Vaswani, Niki Parmar, Llion Jones, and Jakob Uszkoreit. One model to learn them all. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.05137, 2017.

[79] Xi Chen, Xiao Wang, Soravit Changpinyo, AJ Piergiovanni, Piotr Padlewski, Daniel Salz, Sebastian Goodman, Adam Grycner, Basil Mustafa, Lucas Beyer, et al. Pali: A jointly-scaled multilingual language-image model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.06794, 2022d.

[80] Zi-Yi Dou, Aishwarya Kamath, Zhe Gan, Pengchuan Zhang, Jianfeng Wang, Linjie Li, Zicheng Liu, Ce Liu, Yann LeCun, Nanyun Peng, et al. Coarse-to-fine vision-language pre-training with fusion in the backbone. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07643, 2022.

[81] Ting Chen, Saurabh Saxena, Lala Li, Tsung-Yi Lin, David J Fleet, and Geoffrey Hinton. A unified sequence interface for vision tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07669, 2022c.

[82] Aishwarya Kamath, Mannat Singh, Yann LeCun, Gabriel Synnaeve, Ishan Misra, and Nicolas Carion. Mdetr-modulated detection for end-to-end multi-modal understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp.\ 1780–1790, 2021.

[83] Liunian Harold Li, Pengchuan Zhang, Haotian Zhang, Jianwei Yang, Chunyuan Li, Yiwu Zhong, Lijuan Wang, Lu Yuan, Lei Zhang, Jenq-Neng Hwang, et al. Grounded language-image pre-training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp.\ 10965–10975, 2022d.

[84] Zhengyuan Yang, Zhe Gan, Jianfeng Wang, Xiaowei Hu, Faisal Ahmed, Zicheng Liu, Yumao Lu, and Lijuan Wang. Unitab: Unifying text and box outputs for grounded vision-language modeling. 2021.

[85] Yuan Yao, Qianyu Chen, Ao Zhang, Wei Ji, Zhiyuan Liu, Tat-Seng Chua, and Maosong Sun. Pevl: Position-enhanced pre-training and prompt tuning for vision-language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.11169, 2022.

[86] Chaoyang Zhu, Yiyi Zhou, Yunhang Shen, Gen Luo, Xingjia Pan, Mingbao Lin, Chao Chen, Liujuan Cao, Xiaoshuai Sun, and Rongrong Ji. Seqtr: A simple yet universal network for visual grounding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.16265, 2022a.

[87] Linjie Li, Zhe Gan, Kevin Lin, Chung-Ching Lin, Zicheng Liu, Ce Liu, and Lijuan Wang. Lavender: Unifying video-language understanding as masked language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07160, 2022c.

[88] Chenliang Li, Haiyang Xu, Junfeng Tian, Wei Wang, Ming Yan, Bin Bi, Jiabo Ye, Hehong Chen, Guohai Xu, Zheng Cao, et al. mplug: Effective and efficient vision-language learning by cross-modal skip-connections. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.12005, 2022a.

[89] Andrew Jaegle, Sebastian Borgeaud, Jean-Baptiste Alayrac, Carl Doersch, Catalin Ionescu, David Ding, Skanda Koppula, Daniel Zoran, Andrew Brock, Evan Shelhamer, Olivier J Henaff, Matthew Botvinick, Andrew Zisserman, Oriol Vinyals, and Joao Carreira. Perceiver io: A general architecture for structured inputs & outputs. In ICLR, 2022.

[90] Scott Reed, Konrad Zolna, Emilio Parisotto, Sergio Gomez Colmenarejo, Alexander Novikov, Gabriel Barth-Maron, Mai Gimenez, Yury Sulsky, Jackie Kay, Jost Tobias Springenberg, Tom Eccles, Jake Bruce, Ali Razavi, Ashley Edwards, Nicolas Heess, Yutian Chen, Raia Hadsell, Oriol Vinyals, Mahyar Bordbar, and Nando de Freitas. A generalist agent. arXiv, 2022.

[91] Paul Pu Liang, Yiwei Lyu, Xiang Fan, Shengtong Mo, Dani Yogatama, Louis-Philippe Morency, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. Highmmt: Towards modality and task generalization for high-modality representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.01311, 2022.

[92] Xizhou Zhu, Jinguo Zhu, Hao Li, Xiaoshi Wu, Hongsheng Li, Xiaohua Wang, and Jifeng Dai. Uni-perceiver: Pre-training unified architecture for generic perception for zero-shot and few-shot tasks. In CVPR, 2022b.

[93] Aditya Ramesh, Prafulla Dhariwal, Alex Nichol, Casey Chu, and Mark Chen. Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. arXiv, 2022.

[94] Junhua Mao, Jonathan Huang, Alexander Toshev, Oana Camburu, Alan Yuille, and Kevin Murphy. Generation and comprehension of unambiguous object descriptions. In CVPR, 2016.

[95] Jingwei Huang, Yichao Zhou, Thomas Funkhouser, and Leonidas J Guibas. Framenet: Learning local canonical frames of 3d surfaces from a single rgb image. In ICCV, 2019a.

[96] Yao Yao, Zixin Luo, Shiwei Li, Jingyang Zhang, Yufan Ren, Lei Zhou, Tian Fang, and Long Quan. Blendedmvs: A large-scale dataset for generalized multi-view stereo networks. In CVPR, 2020.

[97] Jianxiong Xiao, James Hays, Krista A Ehinger, Aude Oliva, and Antonio Torralba. Sun database: Large-scale scene recognition from abbey to zoo. In CVPR, 2010.

[98] Grant Van Horn, Oisin Mac Aodha, Yang Song, Yin Cui, Chen Sun, Alex Shepard, Hartwig Adam, Pietro Perona, and Serge Belongie. The inaturalist species classification and detection dataset. In CVPR, 2018.

[99] P. Welinder, S. Branson, T. Mita, C. Wah, F. Schroff, S. Belongie, and P. Perona. Caltech-UCSD Birds 200. Technical Report CNS-TR-2010-001, California Institute of Technology, 2010.

[100] Kenneth Marino, Mohammad Rastegari, Ali Farhadi, and Roozbeh Mottaghi. Ok-vqa: A visual question answering benchmark requiring external knowledge. In Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019.

[101] Mark Yatskar, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Ali Farhadi. Situation recognition: Visual semantic role labeling for image understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp.\ 5534–5542, 2016.

[102] Rowan Zellers, Yonatan Bisk, Ali Farhadi, and Yejin Choi. From recognition to cognition: Visual commonsense reasoning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp.\ 6720–6731, 2019a.

[103] Adam Fisch, Alon Talmor, Robin Jia, Minjoon Seo, Eunsol Choi, and Danqi Chen. Mrqa 2019 shared task: Evaluating generalization in reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.09753, 2019.

[104] Adam Trischler, Tong Wang, Xingdi Yuan, Justin Harris, Alessandro Sordoni, Philip Bachman, and Kaheer Suleman. NewsQA: A machine comprehension dataset. In

Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Representation Learning for NLP, pp.\ 191–200, Vancouver, Canada, August 2017. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi:10.18653/v1/W17-2623. URL

https://aclanthology.org/W17-2623.

[105] Mandar Joshi, Eunsol Choi, Daniel Weld, and Luke Zettlemoyer. TriviaQA: A large scale distantly supervised challenge dataset for reading comprehension. In

Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pp.\ 1601–1611, Vancouver, Canada, July 2017. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi:10.18653/v1/P17-1147. URL

https://aclanthology.org/P17-1147.

[106] Matthew Dunn, Levent Sagun, Mike Higgins, V Ugur Guney, Volkan Cirik, and Kyunghyun Cho. Searchqa: A new q&a dataset augmented with context from a search engine. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.05179, 2017.

[107] Zhilin Yang, Peng Qi, Saizheng Zhang, Yoshua Bengio, William Cohen, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, and Christopher D. Manning. HotpotQA: A dataset for diverse, explainable multi-hop question answering. In

Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp.\ 2369–2380, Brussels, Belgium, October-November 2018. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi:10.18653/v1/D18-1259. URL

https://aclanthology.org/D18-1259.

[108] Tom Kwiatkowski, Jennimaria Palomaki, Olivia Redfield, Michael Collins, Ankur Parikh, Chris Alberti, Danielle Epstein, Illia Polosukhin, Jacob Devlin, Kenton Lee, Kristina Toutanova, Llion Jones, Matthew Kelcey, Ming-Wei Chang, Andrew M. Dai, Jakob Uszkoreit, Quoc Le, and Slav Petrov. Natural questions: A benchmark for question answering research.

Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 7:452–466, 2019. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00276. URL

https://aclanthology.org/Q19-1026.

[109] Alex Wang, Yada Pruksachatkun, Nikita Nangia, Amanpreet Singh, Julian Michael, Felix Hill, Omer Levy, and Samuel Bowman. Superglue: A stickier benchmark for general-purpose language understanding systems. In NeurIPS, 2019.

[110] Daniel Khashabi, Snigdha Chaturvedi, Michael Roth, Shyam Upadhyay, and Dan Roth. Looking beyond the surface:a challenge set for reading comprehension over multiple sentences. In Proceedings of North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (NAACL), 2018.

[111] Melissa Roemmele, Cosmin Adrian Bejan, and Andrew S Gordon. Choice of plausible alternatives: An evaluation of commonsense causal reasoning. In 2011 AAAI Spring Symposium Series, 2011.

[112] Lifu Huang, Ronan Le Bras, Chandra Bhagavatula, and Yejin Choi. Cosmos qa: Machine reading comprehension with contextual commonsense reasoning. arXiv, 2019b.

[113] Todor Mihaylov, Peter Clark, Tushar Khot, and Ashish Sabharwal. Can a suit of armor conduct electricity? a new dataset for open book question answering. In EMNLP, 2018.

[114] Rowan Zellers, Ari Holtzman, Yonatan Bisk, Ali Farhadi, and Yejin Choi. Hellaswag: Can a machine really finish your sentence? In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019b.

[115] Alex Wang, Amanpreet Singh, Julian Michael, Felix Hill, Omer Levy, and Samuel R Bowman. Glue: A multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. arXiv, 2018.

[116] Alex Warstadt, Amanpreet Singh, and Samuel R Bowman. Neural network acceptability judgments. arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.12471, 2018.

[117] Richard Socher, Alex Perelygin, Jean Wu, Jason Chuang, Christopher D Manning, Andrew Ng, and Christopher Potts. Recursive deep models for semantic compositionality over a sentiment treebank. In Proceedings of the 2013 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, pp.\ 1631–1642, 2013.

[119] Daniel Cer, Mona Diab, Eneko Agirre, Inigo Lopez-Gazpio, and Lucia Specia. Semeval-2017 task 1: Semantic textual similarity-multilingual and cross-lingual focused evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.00055, 2017.

[120] Ido Dagan, Oren Glickman, and Bernardo Magnini. The pascal recognising textual entailment challenge. In Machine Learning Challenges Workshop, pp.\ 177–190. Springer, 2005.

[121] Roy Bar-Haim, Ido Dagan, Bill Dolan, Lisa Ferro, Danilo Giampiccolo, Bernardo Magnini, and Idan Szpektor. The second pascal recognising textual entailment challenge. In Proceedings of the second PASCAL challenges workshop on recognising textual entailment, volume 6, pp.\ 6–4. Venice, 2006.

[122] Danilo Giampiccolo, Bernardo Magnini, Ido Dagan, and Bill Dolan. The third pascal recognizing textual entailment challenge. In Proceedings of the ACL-PASCAL workshop on textual entailment and paraphrasing, pp.\ 1–9. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2007.

[123] Luisa Bentivogli, Peter Clark, Ido Dagan, and Danilo Giampiccolo. The fifth pascal recognizing textual entailment challenge. In TAC, 2009.

[124] Hector Levesque, Ernest Davis, and Leora Morgenstern. The winograd schema challenge. In Thirteenth International Conference on the Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning, 2012.

[125] Marie-Catherine De Marneff, Mandy Simons, and Judith Tonhauser. The commitmentbank: Investigating projection in naturally occurring discourse. proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 23, 2019.

[126] Mohammad Taher Pilehvar and os'e Camacho-Collados. Wic: 10, 000 example pairs for evaluating context-sensitive representations.

CoRR, abs/1808.09121, 2018. URL

http://arxiv.org/abs/1808.09121.

[127] Samuel R Bowman, Gabor Angeli, Christopher Potts, and Christopher D Manning. The SNLI corpus. 2015.

[128] Andrew L. Maas, Raymond E. Daly, Peter T. Pham, Dan Huang, Andrew Y. Ng, and Christopher Potts. Learning word vectors for sentiment analysis. In

Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pp.\ 142–150, Portland, Oregon, USA, June 2011. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL

http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P11-1015.

[129] Yuan Zhang, Jason Baldridge, and Luheng He. PAWS: Paraphrase Adversaries from Word Scrambling. In Proc. of NAACL, 2019.

[130] Alexander M. Rush, Sumit Chopra, and Jason Weston. A neural attention model for abstractive sentence summarization.

Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2015. doi:10.18653/v1/d15-1044. URL

http://dx.doi.org/10.18653/v1/D15-1044.